The conventional wisdom is that food access issues are greatest in urban wastelands where there are high concentrations of low-income families. This, the argument goes, is because grocery stores and supermarkets abandoned the “inner cities” along with the mass exodus of many white middle-class residents. In their place grew up smaller convenience stores focused on selling beer and cigarettes. And there is lots of good data that make this case. (A National Housing Institute paper on the topic lays this out quite well and we have written about it here at the Daily Score as well.) But could farm country be a food wasteland too?

A recently released study from the Washington State Budget and Policy Center concludes that rural communities face the biggest barriers to healthy food:

Many rural residents in Washington must travel long distances to grocery stores and therefore have less access to affordable fruits and vegetables. By contrast, people who live in more metropolitan areas or in higher income communities are more likely to have access to stores that offer a greater variety of fruits and vegetables.

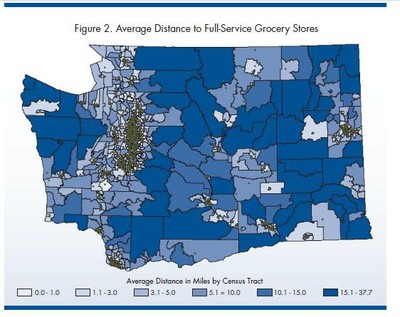

The study maps out the average distance to full-service grocery stores and the results show clearly that rural areas have the biggest distances between people needing healthy food choices and stores that can meet that demand.

The study points out what many other studies have and confirms what is intuitive about food insecurity: less income means a greater likelihood that someone in the household will go hungry.

The greatest struggle in Washington State is in rural counties among workers in “resource-based industries such as timber and fisheries.”

So poverty means food insecurity, and food insecurity is greatest in rural areas. Why is this? The study found that the volatility of fuel prices “impede the ability of lower income residents to reach . . . [stores] which are more likely than smaller groceries and convenience stores to sell healthy food at affordable prices.”

As our gasoline report showed people in the state are getting off the fossil fuels rollercoaster. But in rural areas this is not as much of an option as in our metropolitan centers. The ironic thing is that these rural counties are most often the producers of food we find in our local grocery stores.

The lesson seems pretty clear. Create programs that increase wages, decrease costs of basic needs—food, housing, healthcare—for people struggling with poverty and find ways to get healthier food to the people who aren’t now getting it whether they are in rural or urban areas. And it turns out that part of solving the food insecurity problem might lie in better land use and transportation policies and transitioning workers in resource intensive industries to good paying green jobs.

MP Dunleavey

I’m a personal finance writer (for MSN Money, SELF.com, others), I live in a rural area—and can testify to this bizarre “food insecurity.” Most of the families in my area drive about an hour to Costco and other discount stores, because shopping at Price Chopper, itself a 20 minute drive for many of us, isn’t cheap enough. To make matters worse, or more perplexing, I live in one of the most fertile regions of NY State: the Catskills. In fact, although hundreds of small family farms have closed in the last 50 years, now there is a resurgence of farming in this area, with numerous organic farms taking over the old ones. Unfortunately, ironically, this has not eased the problem one bit. Yes, there is more food available locally—but it’s not affordable for local people. As a freelance journalist, I “telecommute”, and reap the benefits of a bigger economy; i.e. I earn more than the median. But even I find it a struggle to pay $4.00 for a dozen eggs, or $4.25/lb. for free range local chicken, etc. etc.

bill mccord

The avoidable becomes inevitable by unfortunate choices. Having lived in both agricultural and urban communities of Washington during the past 40 years, I have observed too many who’ve either lost and/or failed to obtain the skills to nurture an old-fashioned “victory” garden. While some urban dwellers can defer to the space challenges, there’s little excuse for the rural people who drive many miles to purchase a lot of the groceries that could be supplanted with homegrown options. Predecessors lived frugally, but they cleverly avoided nutritional poverty by gardening [unglamorously with substantive food, e.g. potatoes, beets, carrots,etc.] and preserving that which they could not immediately consume. Valdez’s so-called reporting advances a political agenda that enslaves through dependence on new programs; it disregards the liberating power of self-reliance and community networking that require no new programming except in thinking.