Alan

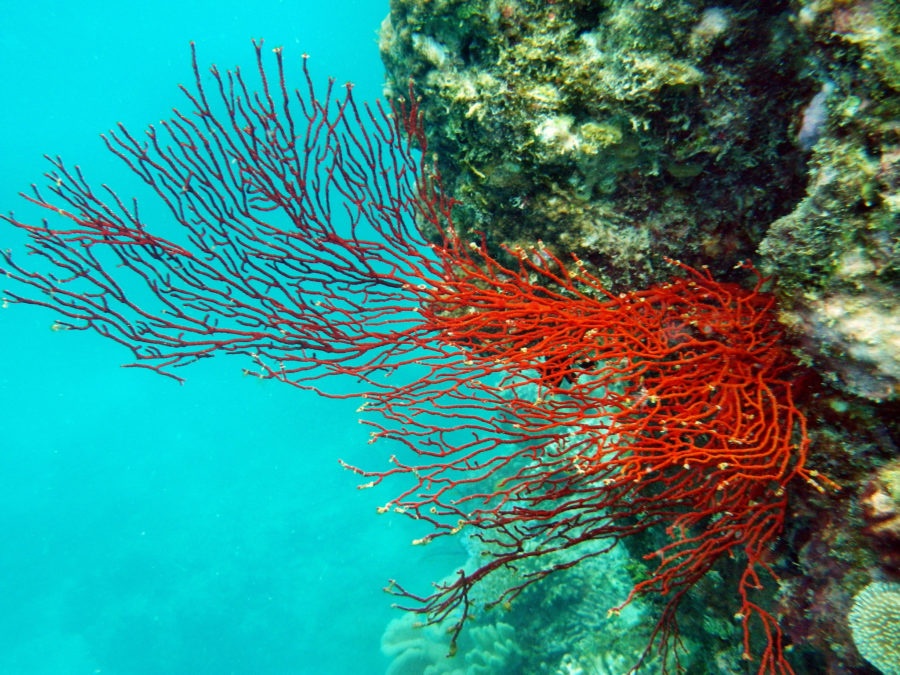

I sat and cried when I read about the large sections of Australia’s Great Reef that are now dead. A mysterious force—call it God, call it the universe—brought us into being on an orb enchanted with life: a miraculous sphere of unimaginable wonders, spinning in the black void of space. Surely, if anything is sacred, it is our home planet.

A big part of the solution to the carbon footprint of long-distance transport (whether air, truck, car, or diesel trains) could be electric-powered fast trains: electric because that lets us power them with renewable sources; fast lets them compete with other modes. If spending $1 trillion on infrastructure were going to mean greening the economy—rather than building monuments to the fossil-fueled past in the forms of highways and pipelines—this idea might figure prominently in public discourse.

The president’s proposed budget would make huge cuts to the Northwest’s world-leading scientific institutions, especially medical research; to EPA; to transit expansion; and more. The list of agencies and programs proposed for elimination includes many I admire for their efficient efforts to correct glaring market failures. One sideline reflection: Most Americans have little love for their federal government because they don’t know what it is. It is largely an enormous institution that collects taxes and borrows money from global financial markets, then distributes checks to others. The entitlement programs, of course, do so. But a huge share of the money flowing through the agencies is also granted to states, localities, tribes, commissions, nonprofits, and other institutions. The only federal enterprises that I can think of that mostly spend their money on their own personnel and equipment are the military, national parks, and the post office (and those three parts of the federal government are among the most respected by the public). Americans tend to like their local government best, their state government middling, and their federal government least. The irony is that the things they do love—their local universities, for example—are often supported by federal funds. Cascadia’s premier public university, for example, is the University of Washington. It gets almost as much money from Washington, DC, as from Olympia, in the form of $1 billion a year in federal scientific research grants. But Washingtonians do not mentally credit the nation when they show their Husky pride. The EPA, for another example, is a small cadre of law enforcers (mostly lawyers), plus a larger number of grantmakers. Local governments get the credit for cleaning up contaminated waterbodies and industrial sites, EPA pays the bills. As if to punctuate this reality came the news this week that the Oregon State Department of Environmental Quality is planning staff cuts because it expects its EPA grants to diminish.

Here’s why going faster doesn’t make you happier; you just drive farther, and mark your calendar for the March for Science on Earth Day. We are called.

Anna

I kind of thought “bandwidth” (in the brain sense) was mostly just corporate jargon or pop psychology, though I’ve definitely used the word myself to describe my own state in frazzled moments. But it’s a real thing. And it can be really serious. Shankar Vedantam (of Hidden Brain—awesome podcast, BTW) got the scoop from two researchers who study scarcity and its effects on our brain function. They show that people in poverty, for example, can compound their troubles by, say spending their last dollars on food rather than saving some of what they have for rent, not because they are foolish or lack foresight, but because the brain’s focus on immediate needs shrinks their capacity for thinking about other things—you actually become less able or unable to expend mental energy on anything else. Scarcity preoccupies and, like a giant file download on a computer, it pushes out everything else. (See, er, hear also: “I’m Right, You’re Wrong!,” Hidden Brain’s research-based examination of why it’s so difficult to change false beliefs, like, fake news claims or climate science rejection.)

Canadians with cystic fibrosis live ten years longer than Americans with the disease—into their fifties instead of their forties. There is no known cure for this genetic disorder but there are treatments and medications. So, why do Canadians fare better? Researchers compared people on both sides of the border, controlling for factors like age, sex, genotype, pancreatic status and more. There are other contributing factors such as diet. But as Aaron E. Carroll, professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine writes in the New York Times, the most significant factor is health insurance. “Canada has a single-payer health care system, which is similar to the American Medicare system. It covers all people in Canada, including those with cystic fibrosis.” Medicare helps take care of those who have it, but many more in the US fall through the cracks. And that’s true for Americans with or without a degenerative disease. Canadians, overall, live longer than Americans and health insurance plays a role—not only in length but in quality of life.

Finally, some clean energy technology eye candy: the Smart Flower. This is so cool.

Eric

Climate activist Alec Connon writes about the six arrestees who went on trial this month for blocking an oil train, and he explains why it was an act of conscience.

Last summer I hiked the 510-miles of the Pacific Crest Trail that traverses Washington, so I was pleased to see the Seattle Times feature the most “wow” worthy parts of that route. Washington state has an embarrassment of scenic riches, but for my money the most spectacular is also the most remote and rugged: the section between Stevens Pass and Stehekin that passes through the western portion of the Glacier Peak Wilderness. I hope the drama of Fire Creek Pass will stay etched in my mind forever.

And I’m ready for summer again. After this endless dark season I’m starting to think the Hungarians are onto something: next year we should try scaring off winter.

Kristin

What if, in addition to the Council of Economic Advisers, the White House had a Council of Social Advisers? Economists bring attention to changes in GDP, but sociologists might bring attention to, for example, the elevated rates of depression, drug addiction, and premature death in the United States. Seems pretty important.

Ontario, Canada, is doing a basic income pilot in areas with high levels of poverty and food insecurity.

This article about “The Decline of Men” has some fascinating statistics, but I found the comments to be interesting: most top comments were some version of “Oh, poor men. Cry me a river.” Which I get, especially when one of the things men have “lost” is a “compliant wife.” But then again, while it’s easy to tell grown men to buck up and carry on without a compliant wife, it’s harder to imagine telling little boys to buck up and soldier on in a childhood that is insecure and an adulthood that seemingly offers them no place. And whether you feel bad for men or boys, the picture is not good for society as a whole. A country full of lost, drunk, violent men who feel they have no role and no roots isn’t good for anyone.