The idea is simple. Instead of setting a single price for Portland’s entire downtown, charge a little more more for overcrowded curbs, a little less for spaces that frequently sit empty, and fine tune prices yearly.

Every time someone parks a car on the street outside Steven Lien’s downtown Portland shop, an invisible clock inside his business plan starts to tick.

If they’re stopping by his men’s underwear store, of course, he’s happy. If they’re not, he’s eager for the minute they’ll finish their errand, get back in their car and move along.

“I can definitely say that when we get more turns on the parking spaces, business goes up,” said Lien, whose shop underU4men takes up a quarter-block and also offers haircuts and massages.

That’s why Lien says he’s all for a proposal, going before Portland’s city council next week, that would lead to raising meter rates along crowded curbs like his above their current $2 per hour.

“Frequency and turnover is really important,” Lien said. “And I think the new studies are showing that if they go to performance-based pricing, the turns can be increased.”

Half a mile away from the bustling sidewalk outside Lien’s shop, Luis Coello has a different problem. The metered parking spaces outside the tiny Old Town shop where he works, Deadstock Coffee, never fill up.

That’s not a big issue for Deadstock’s business, which relies more on foot traffic, but it makes no sense to Coello why he gets a ticket himself when he forgets to run out every two hours and move his car to a different spot along the half-empty curb.

Also, Coello said, the meter rate seems “a little high” at $2 per hour. After all, curb parking never fills up.

The policy Portland’s council will hear next week (and would vote on in subsequent weeks) could fix Lien’s and Coello’s problems at once. The idea is simple. Instead of setting a single price for Portland’s entire downtown, charge a little more more for overcrowded curbs like Lien’s, a little less to people like Coello for spaces that frequently sit empty, and fine tune prices yearly.

If approved, the policy would make Portland the third of the Northwest’s three biggest cities to set meter rates this way. Seattle led the way in 2010 and Vancouver, BC, followed in 2016.

Performance pricing, as cities call these policies, are catching on because they’re good for the economy. They help people in a hurry find convenient parking quickly. They let people on a budget save money by walking a few blocks. And as usual, making prices tell the truth nudges people toward sustainable transportation choices: in the transit-rich heart of downtown Portland, it makes no sense for an hour of parking to cost less than a train ticket.

In Portland’s case, it may also turn out to be a rare thing in government: a revenue reform that has no net impact on public revenue. If approved, prices in some areas would go up and prices in other areas would go down—and in both cases, Portlanders would be using the public space along their curbs more efficiently.

City data shows one meter rate doesn’t fit all of downtown

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Officials say the map above, compiled as a preliminary draft by the city based on meter transactions, awaits more data. Still, it tells the basic story: In large swaths of central Portland, marked by concentrations of gray circles, current meter rates are probably too high. More than one curbside space on many of these blocks is regularly sitting empty.

In other parts of downtown, marked by orange circles, meter rates are probably too low. Hiking them would increase turnover for merchants like Lien and reduce congestion by cutting the time people take to cruise around and find parking.

Here’s another way to see the issue. Portland’s current policy is to charge $2 per hour for parking on a street like this one (photographed during the noon-hour weekday peak):

And also on this one (ditto on time of day):

Any hot dog vendor could tell you: If your product never sells out, it’s time to cut your prices.

Performance-based pricing is responsive pricing

Then there are streets like this one, around the corner from Lien’s shop:

When construction removes a few parking spaces for a year or three, there’s very little impact on downtown as a whole. The same would go for a project that permanently repurposed parking on one street to add a sidewalk cafe or bus lane.

But any of those would have a major impact on their block—and for nearby merchants, even more reason to want quick turnover for the curbside spaces that remain.

Short, small-scale changes like these are exactly why it’s useful to adjust prices in response to parking demand frequently and fine-tune it to the geographic level.

Lien said he thinks the city should check meter use every few months and adjust prices according to a formula, and that the city council should agree on that formula—including minimum and maximum hourly prices—but not wade into directly setting the price in every district itself.

“Data should be the rule, and I actually don’t think the council needs to vote on such stupid little things,” Lien said.

Portland continues to lead the Northwest in using parking revenue to reduce the need for parking

Above are the ways Portland could make the price of parking smarter. But there’s another issue: What to do with the cash meters bring in?

Under a different part of the city’s new policy package, more than half the revenue from any future meter districts in Portland “should” (that’s the word the city uses) be reinvested in measures to reduce that area’s auto dependence.

Options could include dedicated bus lanes, transit discounts for employees and residents, crosswalks or protected bike lanes.

Though a similar policy has been proposed on a pilot basis in Seattle, we don’t know of any other Northwest jurisdiction that’s doing it.

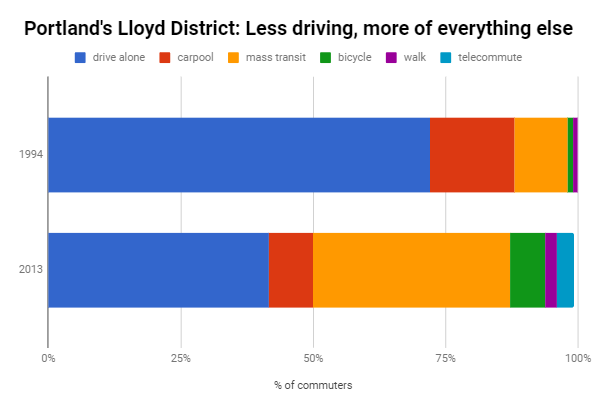

But it’s nothing new in Portland, which pioneered this model in the Lloyd District in 1997 and has seen a major payoff since:

In the last two years, Portland duplicated the Lloyd model for new meter districts in the Central Eastside and Northwest Portland: both meter districts now fund driving-reduction benefits for their areas.

In the last two years, Portland duplicated the Lloyd model for new meter districts in the Central Eastside and Northwest Portland: both meter districts now fund driving-reduction benefits for their areas.

Next week’s council vote could enshrine this practice into permanent city policy for future meter districts. (For Portland’s existing downtown meter district, by far the city’s most lucrative, Tony Jordan of the advocacy group Portlanders for Parking Reform said Transportation Commissioner Dan Saltzman has promised a separate public process considering how to divvy its revenue.)

As we’ve written before, this parking-revenue reinvestment rule is one of the three key policies recommended by parking-reform visionary Donald Shoup.

“If everybody sees their meter money at work, the new public services can make demand-based prices for on-street parking politically popular,” Shoup, a longtime UCLA professor, wrote in his latest book.

Smarter parking can mean more equitable transportation

For Jordan, the parking reform advocate, that reinvestment policy—charge more for parking, but spend the money to improve the alternatives—is a key in mitigating any disproportionate costs on lower-income Portlanders.

“Any inequity that’s created by the parking system should be addressed with the related policies for housing and transit,” Jordan said. “It fits in with bus rapid transit. It fits in with housing policy. It fits in with climate action.”

Zan Gibbs, the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s equity and inclusion program manager, said in a June interview that she’d been asked to look over the city proposal for potential downsides to public equity.

“We spent an hour just talking through some basics, and I didn’t see anything I would immediately change,” Gibbs said.

In part, she said, that’s because city-owned parking garages—which happen to sit in areas where meter rates would likely rise—already offer a discount rate for night workers whose shifts catch the start or end of Portland’s metered parking hours.

Gibbs added: “It would actually allow for a much easier time in general for folks to find parking downtown. I see a lot of advantages to that, particularly if they’re low-wage workers, if they’re running late, if they’re trying to drop off kids.”

In the end, that’s the rationale of parking reform: Sometimes, what people need most isn’t 25 cents. It’s 10 minutes. When we let people of all incomes weigh those tradeoffs for themselves—while also using public revenue to give a leg up to those of us with less—we make city life a little better for everyone. That’s what would make Portland’s proposed parking reform one of the best the Northwest has seen in years.

Daniel

All this talk about transportation equity with transit, bicycling, and walking serves to stigmatize and exceptionalize lower income people. This refrain in Portland is familiar whether it be with parking or road congestion. Always point to lower income people. It’s shameful that Government types are stigmatizing and exceptionalizing a community like this in order to get their projects through while justifying the need for their jobs.

Cedric Justice

Instead of changing process yearly, why not go for the gusto and have them change weekly? There are ways to do these analyses from geeks like me who use data to change policy all the time? Or you can program the meters to be reactive and if the blockface is more than 60% utilised, raise prices, 80%, raise again, etc.

I know that practically, they’re probably not sending price signals to the meters, but utility companies have been for at least 10 years. It’s possible… But I know, probably not entirely practical, as the infrastructure to enable that may be onerous at this point.

Nevertheless, a nice nerd problem for analysts like me.

DaveB

“Any hot dog vendor could tell you: If your product never sells out, it’s time to cut your prices.”

But, wait, do we really want to sell more parking/keep spaces full? In theory lower rates might induce some drivers to park a block from their destination but only if they could tell the meter rate as they driving by (or if the city is proposing an app as part of the package.