Seattle is in the process of updating its Comprehensive Plan, its 20-year roadmap for growth. Chief among the policies it charts is, of course, housing. Seattle’s chronic shortage of homes and the harm that has done to lower-income residents and communities is no secret to anyone.

Unfortunately, the draft plan falls far short of what’s necessary to create a Seattle that welcomes households of all incomes. In short, it doesn’t make enough room for more homes.

If adopted as proposed, more and more people will continue to be priced out of the city for decades to come. And the city will also fall further behind on goals to reduce climate pollution and sprawl.

The critical fix is straightforward: loosen zoning rules to allow more homes of all shapes and sizes. And Seattle can improve its draft Comprehensive Plan to make that happen in three key ways. (I cover them briefly in the numbered sections below, then expand on each in the rest of the article.)

1. Let middle housing with more homes be bigger

Allowing middle housing—small-scale homes like fourplexes—in places once reserved for detached houses is an imperative for creating more homes that more people can afford in lower-density neighborhoods.

The good news is that the 2023’s Washington state bill HB 1110 requires Seattle to legalize middle housing in areas currently reserved for single-detached houses. Three-quarters of Seattle’s residential land will be opened up to more housing, creating the potential for tens of thousands of new homes.

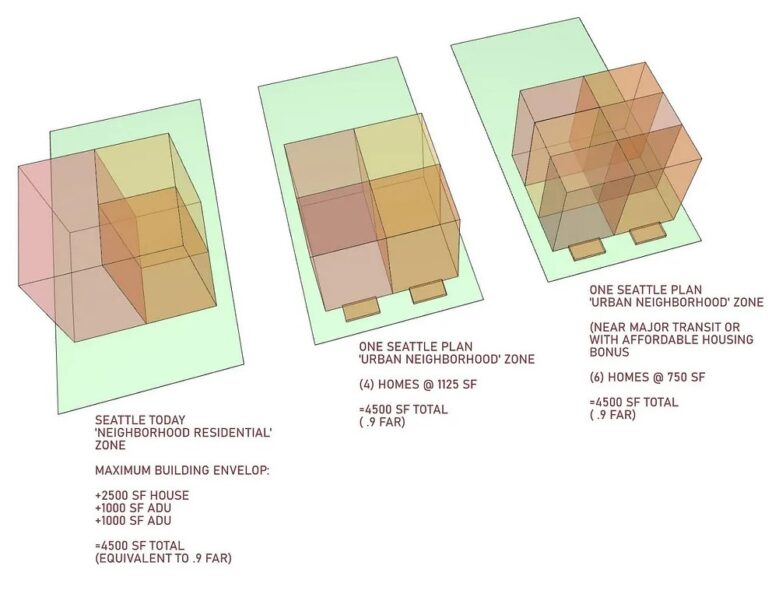

The bad news is that just allowing more homes per lot doesn’t by itself guarantee anything will get built. That’s because middle housing construction is usually not financially feasible unless zoning rules allow the buildings to add indoor space as their unit count goes up. Seattle’s proposed Comprehensive Plan (Comp Plan, for short) doesn’t do that, and instead would impose the same cap on buildable capacity as what currently applies to single-detached houses with accessory dwellings. This limitation would not only suppress the construction of middle housing but would also prevent any feasible projects from having family-sized homes.

The solution is to emulate Spokane’s best-in-the-US middle housing zoning, which grants generous development capacity and flexibility. Or, at minimum, implement the middle housing capacity recommendations of Washington’s Department of Commerce, which stipulate workable increases in capacity. More below.

2. Allow larger apartment buildings in more of the city

Apartment buildings five stories and up, near job centers, transit hubs, mixed-used nodes, schools, and parks, are essential for providing the level of density that both reduces cost and adds homes at the scale needed to address Seattle’s shortage. Large multifamily buildings in compact, walkable, low-carbon neighborhoods also yield the biggest dividends on reducing climate pollution and sprawl.

Seattle’s draft Comp Plan proposes only a modest amount of upzoning for apartment buildings. It recommends four- to six-story buildings in 24 newly designated “neighborhood centers” confined to just an 800-foot radius, and eight stories in a new urban center at the 130th Street light rail station. Otherwise, it proposes no apartment upzones anywhere else, excepting some slivers of land currently zoned for low density in designated centers, and possibly some 1/2-block strips along arterials.

Seattle’s plan could rise to the moment by allowing highrise towers in all regional centers and near all light rail stations, eight-story buildings in all urban centers, and six-story buildings near frequent transit stops and other community amenities like parks. It could also designate more and larger neighborhood centers with apartment zoning.

That may sound like a lot of change, but it’s still not European-caliber density, to say nothing of Asian standards. It’s not even as ambitious as what neighboring British Columbia adopted in November—and not just in the biggest city of Vancouver but provincewide. More below.

3. Legalize car-free homes everywhere

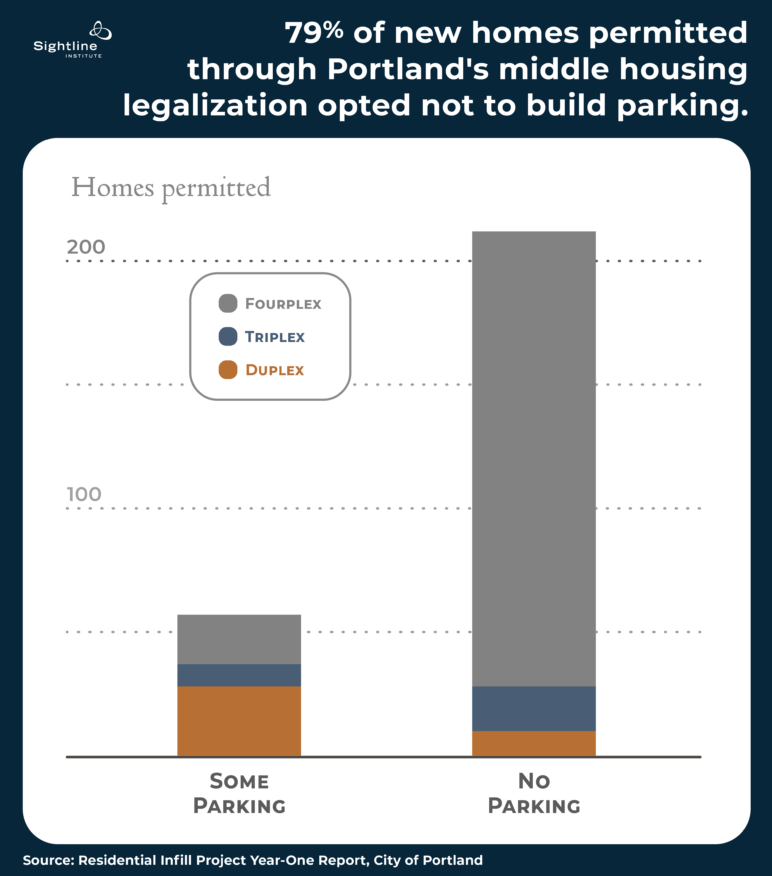

Requiring new housing to come with parking prioritizes storage for cars over homes for people. Parking reduces the amount of housing that can be built, while at the same time increasing its cost.

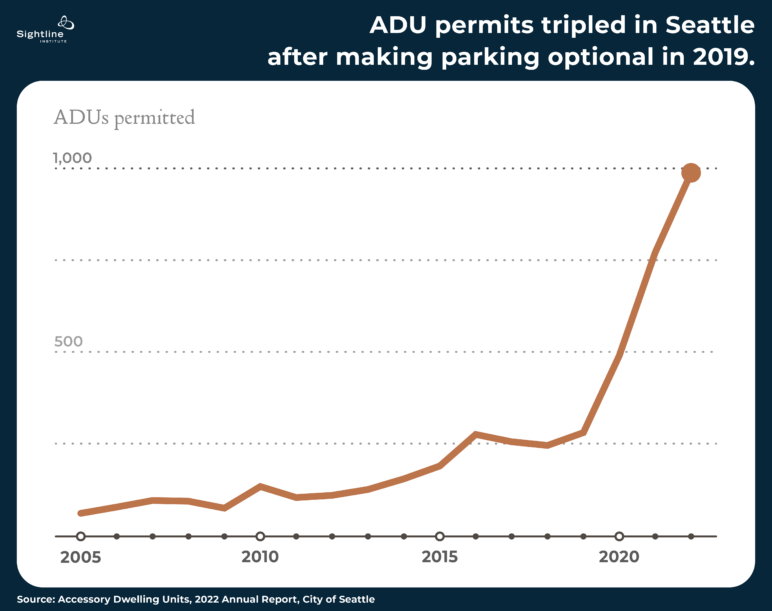

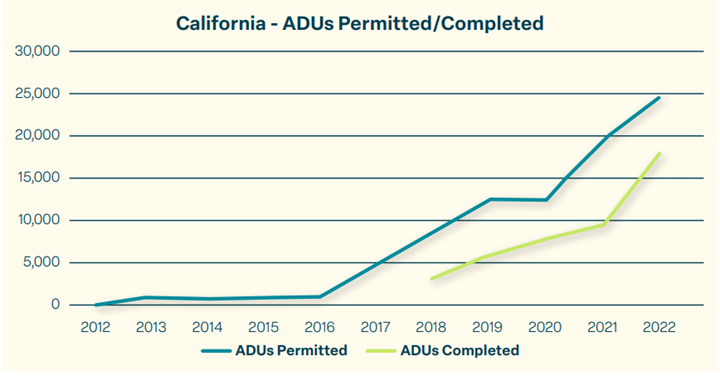

In 2012, Seattle eliminated parking mandates in its designated centers and reduced them near transit. But the city still requires off-street parking on the majority of residential lots, especially in areas that will be zoned for middle housing, which is particularly vulnerable to death by parking mandate.

There couldn’t be a simpler solution for avoiding the lose-lose outcome of more unneeded parking and less housing: Seattle can eliminate parking mandates citywide. This reform would not ban parking. Home builders could still include parking if they wanted to, and many no doubt would. Ending mandates only ensures that our laws no longer force the overbuilding of parking, and that translates to more new homes and less expensive new homes.

Already, Portland, Anchorage, Buffalo, Minneapolis, Austin, San Jose, Raleigh, Hartford, and 60 other North American cities have completely eliminated off-street parking requirements, freeing space for more homes. Seattle would do well to join this forward-thinking group of cities. More below.

Why Seattle leaders need to do (a lot) more with the Comp Plan

In a housing crisis caused by a shortage of homes, policymakers should do everything they can to allow more homes. Before I detail the three key fixes named above, some words about why Seattle leaders need to be bolder in their housing vision for the city’s future.

The draft plan’s target numbers are weak

Seattle’s draft plan is based on a target of 100,000 new homes over the next 20 years. First, that’s only 20,000 more homes than status quo projections expected, even with no changes to existing zoning. Second, an average rate of 5,000 new homes per year is far lower than the housing growth that has actually occurred in recent years. For example, from 2013 to 2023, Seattle added an average of nearly 8,500 new homes per year.

Zoned capacity ≠ built reality

Seattle planners estimate that current zoning has capacity for 168,000 more housing units, which may lead one to ask: why, then, does the city need to loosen zoning at all? The reason is that zoned capacity is a theoretical number that overstates reality. What I wrote in 2016 is even truer today:

Zoned capacity is not plentiful in Seattle. If it were, housing prices wouldn’t be going through the roof. The fact that housing prices are skyrocketing is the smoking gun of our severe shortage. If vacancy rates are low and rents and housing prices are rising, then a city needs to remove zoning-code barriers so that builders can construct more homes.

Go big, so more people can go home

There is no downside to erring on the side of too much upzoning that comes anywhere close to the catastrophic downsides of maintaining restrictive zoning that worsens Seattle’s housing shortage. Today, far too many Seattleites face crushing housing insecurity caused by the zoning status quo. The strongest predictor of homelessness rates is high rents and low vacancy rates—both of which are caused by a scarcity of homes.

Are Seattle’s leaders worried that they might let too much housing get built in a housing crisis? If not, then they should put their money where their mouth is and ensure that their next Comp Plan sets zoning policies to boost home building in every way possible.

Okay, back to the details for each of the three key improvements I named in the introduction.

Small apartment buildings like this one in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood were once allowed almost everywhere in the city. Photo by Dan Bertolet.

Get the details right for middle housing

Zoning reforms in other parts of the US have demonstrated that even when middle housing is legalized, not much will be built unless the rules allow the buildings to be larger than single-detached houses. Developing middle housing on small lots tends to be a money-losing proposition unless zoning allows more development capacity for projects that incorporate more homes.

The earliest example is Minneapolis’ 2019 legalization of triplexes, where only a handful have been built because the zoning caps their size at the same as standalone houses. Analysis of Portland’s middle housing zoning showed that its incremental increases in capacity for more homes was still not enough to make construction feasible in most cases.

Washington’s Department of Commerce took this into account when developing its middle housing model code (see Sightline’s comments on the draft). It recommends granting an increasing amount of floor area ratio (FAR), starting at FAR 0.8 for duplexes and rising stepwise to FAR 1.6 for sixplexes.

Increase the FAR, especially to allow family-sized middle homes

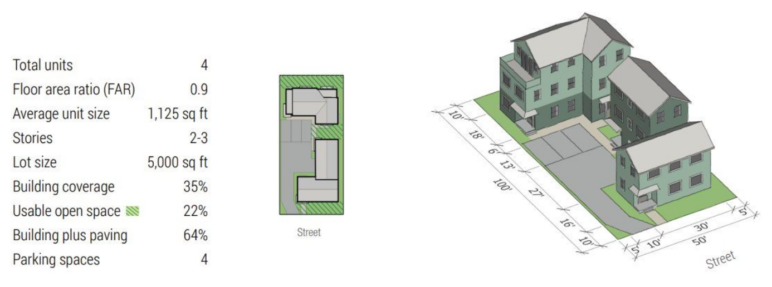

Seattle’s draft plan caps FAR at 0.9 for all middle housing, regardless of the number of units. That’s the same FAR currently allowed for a house and two accessory dwellings on a standard 5,000-square-foot lot. It’s a formula for an anemic pace of middle housing construction.

It’s also a formula for essentially banning middle housing with family-sized homes. On a 5,000-square-foot house lot, FAR 0.9 means 1,125-square-foot units (on average) in a fourplex, or 750 square feet in a sixplex. If they are typical townhouses, the staircases eat up a large fraction of that already limited living space. For comparison, under the Commerce model code, a sixplex’s units could be 1,333 square feet, enough for a three-bedroom apartment.

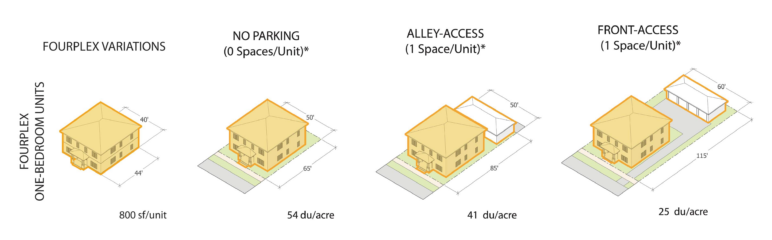

Seattle’s draft Comp Plan proposes to cap FAR at 0.9 for all middle housing, which forces smaller homes as the unit count goes up and compromises the financial feasibility of construction. Image by CAST Architecture, used with permission.

Go beyond FAR, like Spokane

But Seattle’s plan can aim even higher. Spokane set the bar for North America with the citywide middle housing zoning it adopted in late 2023. It limits building size not by FAR, but by lot coverage, setbacks, and height. It has no limit at all on the number of units on a lot. Its most restrictive tier would allow a four-story building with a FAR of just under 2.0. A typical 5,000-square-foot house lot could accommodate an eightplex with two approximately 1,200-square-foot apartments per floor, in a building covering half of the lot.

Enabled by Spokane’s new zoning, the “Spokane Six” (see image above) currently in development demonstrates a sixplex prototype that Seattle’s next-generation zoning should be tailored to allow. It would be impossible under Seattle’s paltry proposed limit of FAR 0.9.

The “Spokane Six,” a sixplex currently in development, enabled by Spokane’s best-in-nation middle housing rezone. Image by CAST Architecture, used with permission.

Boost stacked flats > townhouses, especially for accessibility

Townhouses—attached homes divided vertically from each other and sold separately with the land underneath them (“fee simple”)—are by far the most common type of middle housing built in Seattle today, and that will continue to be true under compliance with HB 1110 and under the city’s draft Comp Plan (see the city’s illustrations).

Townhouses work well for many households and provide an entry into ownership at a lower cost than detached houses. However, one major drawback is they are inaccessible to people who can’t use stairs. In contrast, stacked flats like the Spokane Six can provide accessible, single-level homes on the first floor, and on higher floors, too, if there’s an elevator.

In fact, federal law mandates that in multifamily buildings with four or more units, every ground-floor home must be wheelchair-accessible—good for people with disabilities and for the US’s booming aging population, for whom aging-ready homes are drastically undersupplied to meet future demand.

If Seattle hopes to see much stacked-flat middle housing construction, it will need to give it a leg up to overcome the inherent economics that favor townhouse development. Two good ways to do that:

- Grant more FAR for stacked flats than for townhouses. The FAR of 1.6 recommended by Commerce would be sufficient.

- Allow at least six units per lot for any stacked-flat development. Or better yet, remove the unit cap altogether, as Spokane did.

Avoid the poison pill of affordability requirements

Seattle’s brand of inclusionary zoning (IZ), called “mandatory housing affordability” (MHA), applies to middle housing where it is currently allowed, requiring builders to include below-market-rate homes or pay a “fee in lieu” into the city’s affordable housing fund. The draft plan is mute on MHA, though it’s safe to assume that it will be considered when rezones are implemented.

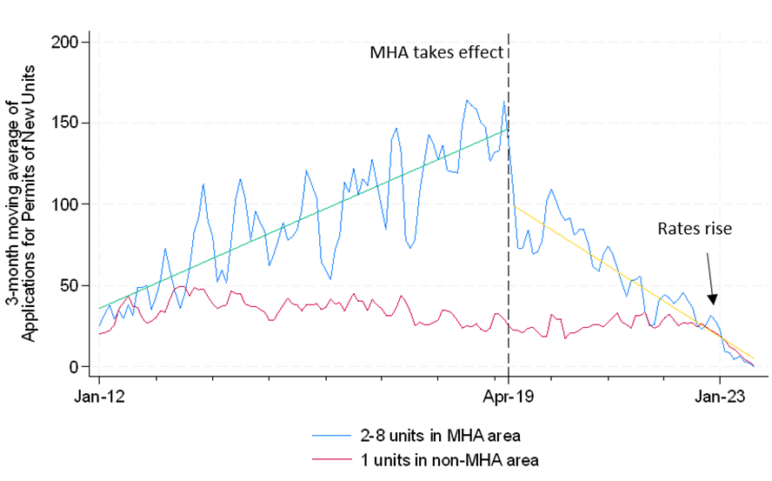

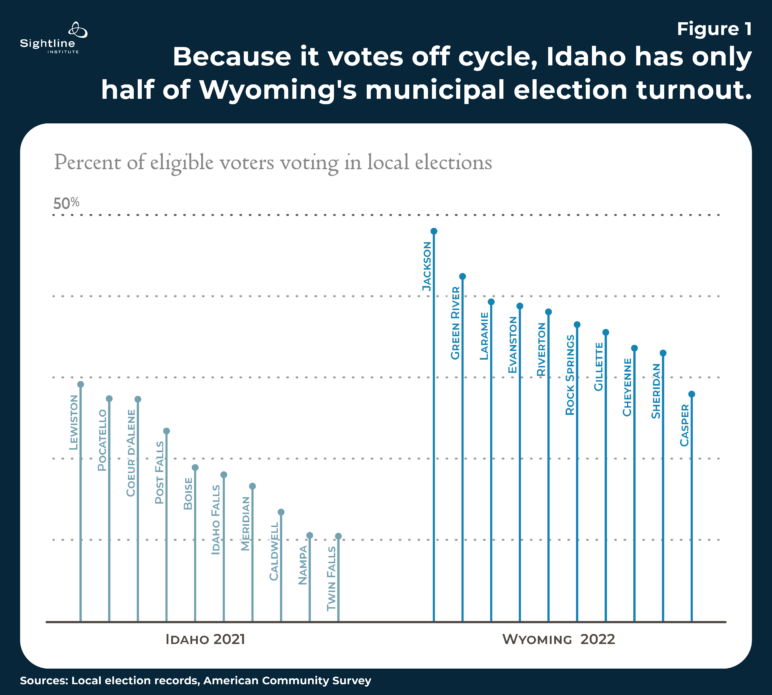

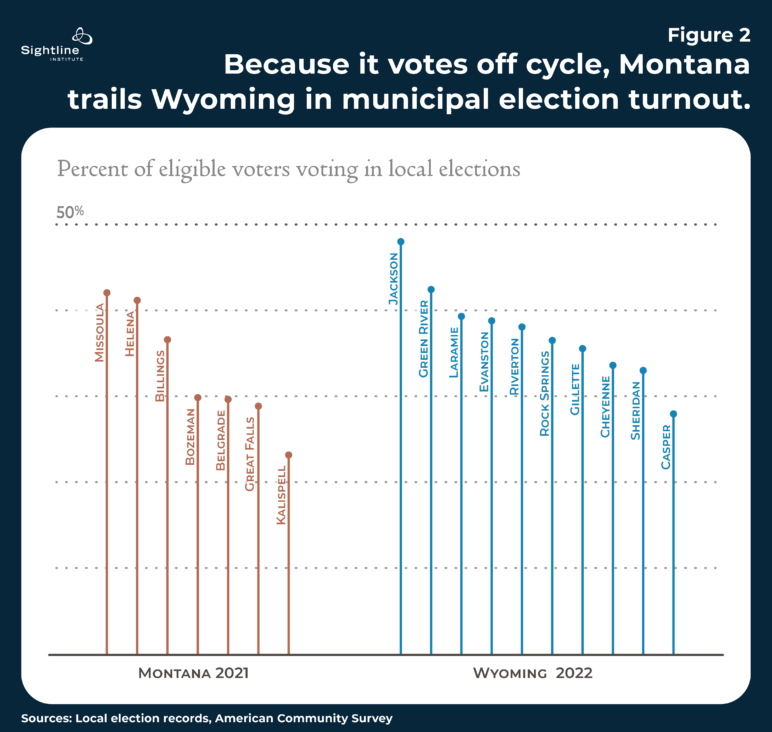

In 2017, Sightline’s analysis projected that MHA would be particularly harmful to middle housing production. Since then, studies of permit data (see graph below) and avoidance support that conclusion.

Seattle permits for townhouse construction dropped after April 2019, when the city adopted its MHA program that requires affordable units or payment of an in-lieu fee. Interest rates rose in 2023, long after the decline in production began. Sources: City of Seattle data and American Enterprise Institute, used with permission.

It is generally accepted that affordability requirements are a bigger financial hurdle for small-scale home builders, and IZ programs in other cities commonly exempt small projects, say, with 10 units or fewer. The architects of Washington’s middle housing bill, HB 1110, recognized this limitation and did not mandate affordability but instead granted the option to add more homes if a portion were set aside as affordable. The Pacific Northwest’s leaders on middle housing reform, Portland and Spokane, do not require IZ for middle housing.

Best available evidence indicates that imposing MHA with Seattle’s future middle housing upzones would undermine the intent of the upzoning in the first place. It would suppress middle housing construction, depriving residents of less expensive housing choices and prolonging the city’s dire housing shortage that harms those with the least, the most. Seattle policymakers can maximize all the benefits of middle housing with one simple move: don’t impose MHA on it.

A six-story apartment building in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood. Photo by Dan Bertolet.

Create apartment building abundance

Over recent decades, the vast majority of Seattle’s new housing has come in the form of apartment buildings, four stories and up. Seattle’s past planners deserve credit for creating the multifamily zoning that largely enabled the city’s population to grow from 563,000 to 779,000 between 2000 and 2023, a gain of 38 percent—while the population in Seattle’s single-family areas largely stagnated or even declined.

Allow apartments in more places

The catch is that Seattle’s apartment zoning is confined to a small fraction (about 13 percent) of its residential land, located almost entirely in designated urban centers and villages and along arterial streets. Seattle’s booming growth and robust job creation has rendered that 30-year-old strategy of confinement insufficient for meeting the city’s housing needs. Furthermore, the city’s own study concluded this “urban village” strategy has exacerbated racial segregation and inequity.

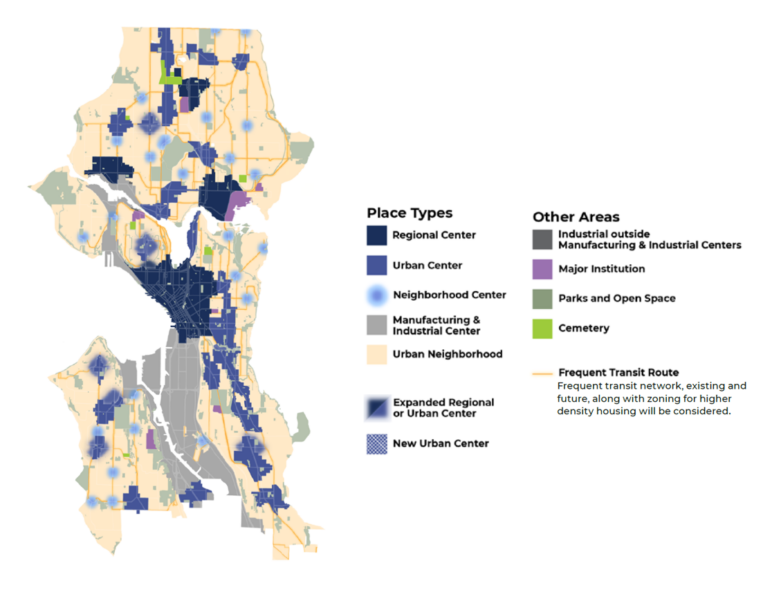

Draft Seattle Comprehensive Plan future land use map and legend showing locations of newly designated neighborhood centers (faded light blue) and other types of centers. Source: City of Seattle.

Seattle’s plan can expand opportunities for apartments and condos in multiple contexts and scales by allowing (see map above for reference):

- Highrise towers throughout all regional centers and within a quarter-mile of all light rail stations outside regional centers,

- Eight stories throughout all urban centers, and

- Six stories within a quarter-mile of all frequent transit stops, schools, parks, libraries, and community centers.

Add more “neighborhood centers,” and enlarge them

The city can further expand apartment choices by designating more neighborhood centers and making them larger. The draft plan states that in these centers, “residential and mixed-use buildings of four to six stories would be appropriate.”

These two changes would be especially beneficial for creating opportunities for apartments located away from dangerous, polluted, and noisy arterial roads, where current apartment zoning is concentrated. Plentiful apartment zoning also supports the development of subsidized affordable housing, because its most common form is midrise apartment buildings.

An earlier proposal identified some 48 potential neighborhood centers, but only 24 made their way into the draft plan officially released last month after Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office scaled back changes (compare this map from the earlier draft with the one shown above). Also, the proposed size for neighborhood centers is only an 800-foot radius, which is just a few blocks. A quarter-mile radius would allow the critical mass for a functional center.

New highrise residential towers in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood. Photo by Dan Bertolet.

Follow Portland’s example, in apartments and in funded affordability mandates

Portland, Oregon, is poised to lead the US in allowing more apartments, the next logical step after that city’s 2020 legalization of middle housing citywide. An advocate-led effort proposes legalizing midrise apartment buildings throughout the city’s Inner Eastside neighborhoods.

Seattle policymakers can also look to Portland for a better way to do IZ—namely, one that doesn’t undermine its own intent by suppressing construction. Earlier this year, Portland modified its IZ program to ensure that the cost of providing the required affordable homes is fully offset by a property tax exemption and other fee reductions. That is, Portland fully funds its IZ. It’s a win-win-win: apartment construction continues apace, every new apartment building includes some homes for lower-income residents, and the new building’s property tax revenue pays for its new low-income units.

Say goodbye, once and for all, to costly parking mandates

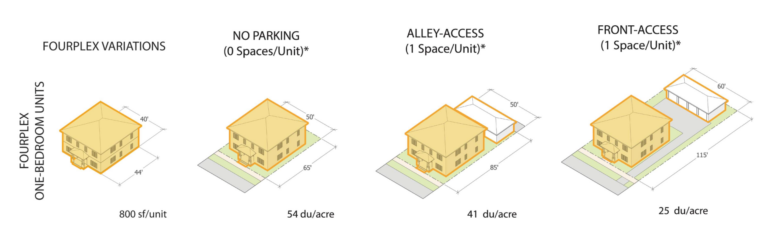

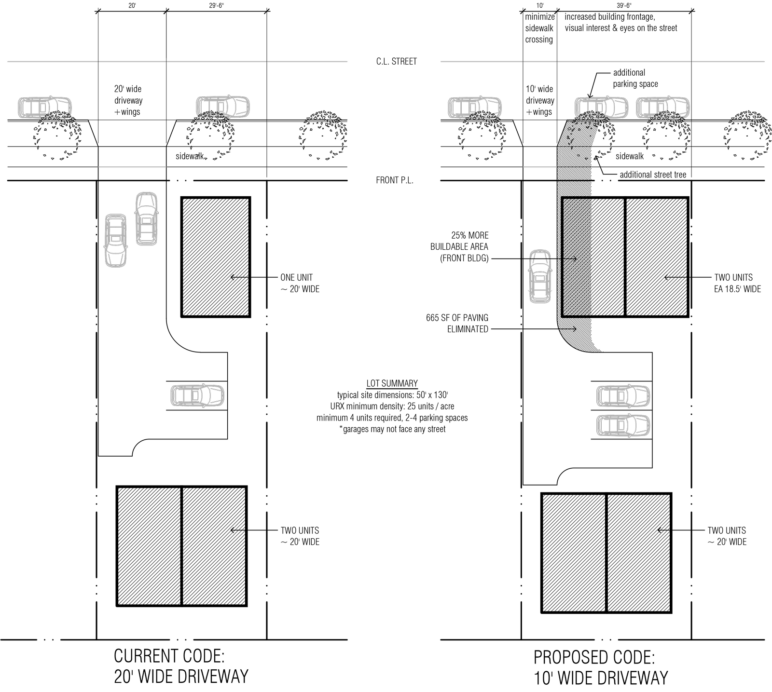

Seattle’s draft Comp Plan does a good job of summarizing how requiring off-street parking is bad policy because it “increases the cost of construction; reduces the amount of space available for housing, open space, and trees; increases hardscape and stormwater runoff; and encourages vehicle ownership and use.”

The plan further explains that parking mandates are especially problematic for middle housing: “On small lots, driveways, maneuvering areas, and parking stalls can take up a substantial portion of the site and dictate the layout of everything else on the site.” See the city diagram below for an example of how much space parking eats up on a standard lot.

City of Seattle diagram of potential middle housing with four units per lot, illustrating the large portion of the site taken up by pavement for four parking spaces. Source: City of Seattle.

Sightline has documented in detail how parking mandates are a death knell for middle housing, concluding that “to unlock the full potential of small-scale homes, there is no policy debate: parking minimums have to go.”

Meanwhile, the only benefits of off-street mandates offered by Seattle’s draft plan are that they can “reduce competition for parking on the street” and “support goals like providing space for electric vehicle charging.”

The plan’s assessment is both clear and accurate: the benefits of ending mandates vastly outweigh the benefits of keeping them. Yet the plan takes no position, stating only that the city is “considering whether to remove parking requirements in remaining areas where they are present today.”

Seattle’s current rules for parking flexibility apply within a quarter-mile of frequent transit stops. For residential parcels that are also located inside designated urban centers or villages, no parking is required. Otherwise, parcels with quarter-mile transit proximity get a 50 percent reduction from the city’s standard parking mandates.

This map shows all the land eligible for parking flexibility, but it doesn’t differentiate between areas with full elimination versus 50 percent. Urban centers and villages cover a small fraction of Seattle’s residential land, so a large portion of the dark areas in the map still require some parking. Even a mandate of one space for every two homes can be a deal breaker for middle housing.

Requiring one parking space per home for a fourplex can reduce the density by one half. From Missing Middle Housing by Daniel Parolek, Chapter 5 Missing Middle Housing Types, pages 130-131. Copyright © 2020 Daniel Parolek. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Complete HB 1110’s unfinished business on parking flexibility

Ideally, HB 1110 would have prohibited local parking minimums for middle housing, but it almost certainly would not have passed the legislature with that additional, politically controversial pre-emption.

If Seattle policymakers retain parking mandates, they are choosing to prioritize reducing competition for street parking over creating homes for people—in a housing crisis.

The bill did, however, include a provision to make it easier for cities to remove their mandates. It exempts from state environmental review any actions local governments take to reduce parking requirements. Seattle, the biggest, most urban city in Washington, can complete the unfinished business of HB 1110 on parking and set an example for the entire state. Washington’s current leaders on parking reform are Spokane, which nixed requirements on nearly all of its residential land, and Port Townsend, which ended all mandates but with an ordinance that’s only temporary.

Of course, many builders will opt to include parking with middle housing even if it’s not required by law. But if it is required by law, many middle housing projects will become more expensive or will never get built at all.

If Seattle policymakers retain parking mandates, they are choosing to prioritize reducing competition for street parking over creating homes for people—in a housing crisis. Correcting that priority is easy: just use the delete key on Seattle’s remaining off-street parking mandates, joining the wave of hundreds of other American cities making similar reforms.

Seattle cannot afford to miss this opportunity

Seattle updates its Comprehensive Plan only once every eight to ten years, and the new housing it shapes will be around for 50 to 100 years. The housing security of thousands—tens of thousands—of current and future residents depends on the city embracing a plan to allow enough new homes, in all shapes and sizes, over the coming decades. Seattle’s crisis of spiralling rents and prices, caused by a shortage of homes, calls for policymakers to take every action possible to undo that shortage.

Sadly, the city’s current draft plan does not do this. It proposes some positive steps, but overall, it fails to move much beyond the status quo that created Seattle’s housing problems in the first place. An earlier, unpublished version of the draft plan put forward by the planning department did propose more aggressive changes to allow more housing, but Mayor Harrell’s office scaled it back before it was officially released.

Seattle’s plan can meet the moment with three key improvements:

- Get the zoning details right for middle housing to ensure that its feasible to build and can provide family-size and accessible homes

- Boost allowances for bigger apartment buildings throughout the city to create more homes more people can afford in places with access to opportunity and transportation options

- Eliminate requirements for off-street parking citywide to end the wasteful, costly overbuilding of parking and to make housing less expensive and more abundant

With these reforms and the abundant housing they help create, Seattleites for decades to come will benefit from greater affordability and environmental sustainability.

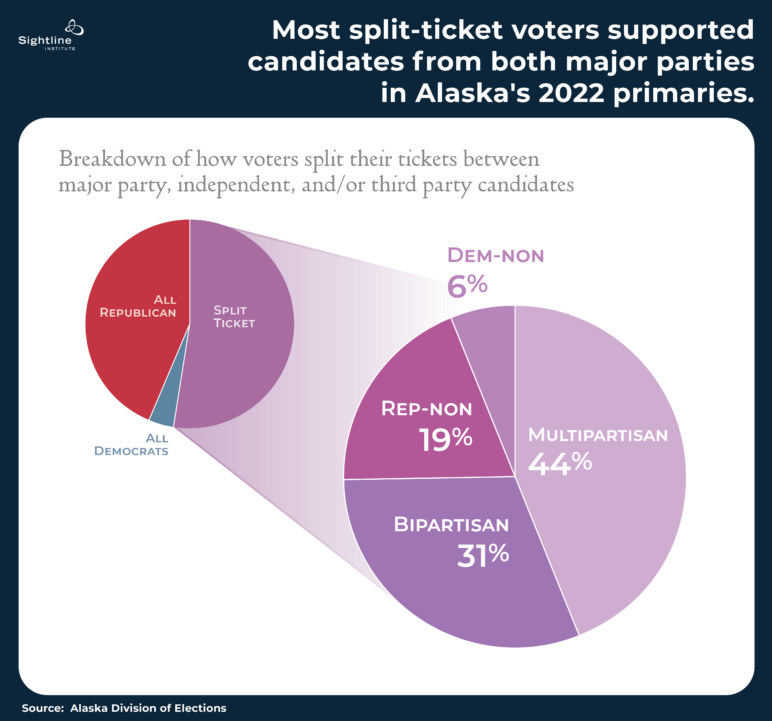

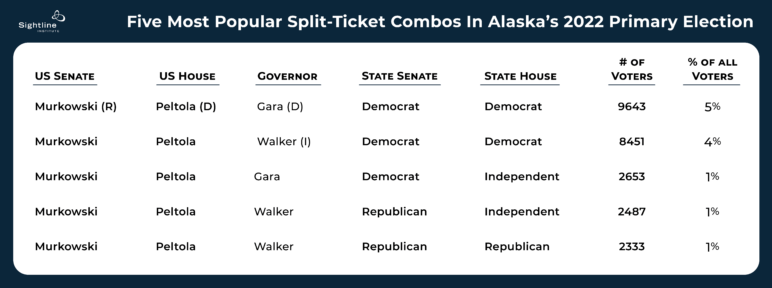

![The majority of residential properties [in orange] in Kent’s Greenfield Park neighborhood cannot add the one parking space required for an accessory dwelling unit. Image by Cast Architecture. Used with permission.](https://www.sightline.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Greenfield_Park_Parking_Restriction_Analysis-772x383.png)