Can’t the Northwest states just ban Big Money in citizens’ initiatives?

Unfortunately, the answer is no.

The US Supreme Court has forbidden limits on money for ballot measures, a lamentable state of affairs that may take a decade or more to reverse through favorable judicial appointments and new jurisprudence. That’s a long-term undertaking, but it’s an achievable one. The New York-based Brennan Center for Justice and others are already engaged in building the new legal philosophies and establishing precedents. (Unfortunately, current legal trends are moving in the opposite direction.) In the meantime, the Northwest can protect and strengthen its best-in-class rules for full disclosure of initiative funders. It can also join Iowa in making corporate boards or shareholders vote to authorize initiative spending.

SCOTUS on Initiatives

The timeline of federal court rulings is disheartening.

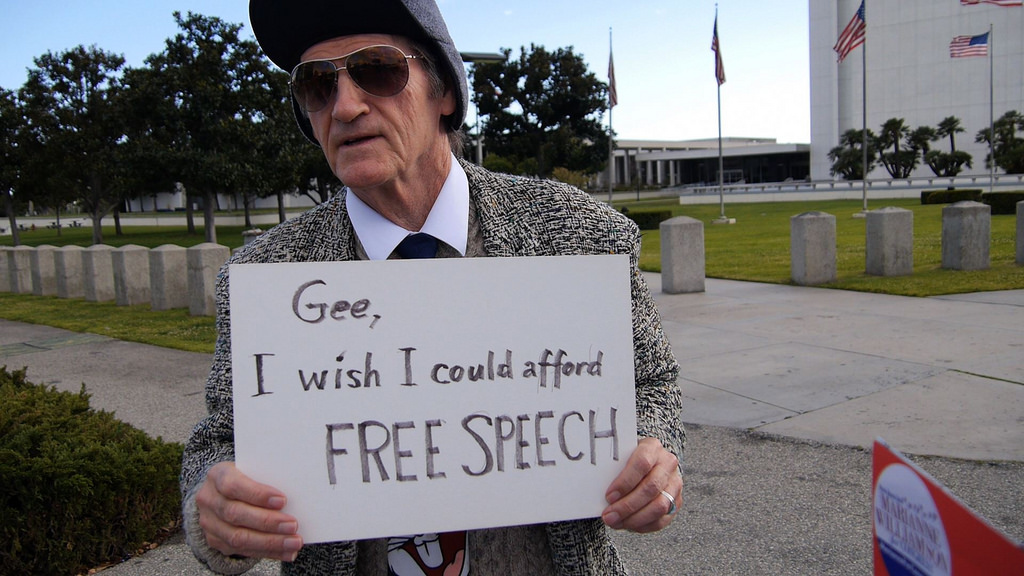

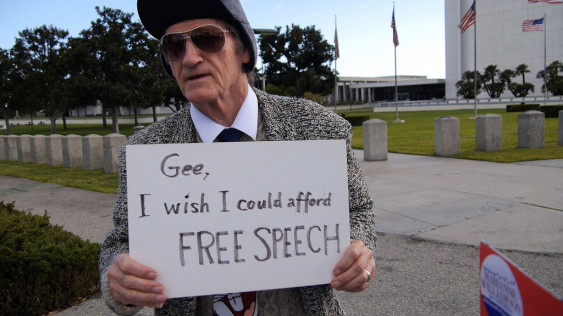

In 1978, in First National Bank of Boston v. Belotti, the Supreme Court interpreted the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech as a prohibition on spending limits on ballot measure campaigns, even by private corporations. The case, a stepping stone on the path to Citizens United, applied an exceedingly narrow definition of corruption—as quid pro quo, or “money for votes”—to conclude that a ballot measure campaign simply cannot be corrupted. “The risk of corruption perceived in cases involving candidate elections simply is not present in a popular vote on a public issue.” In the Northwest nowadays, the whole enterprise often seems corrupt, as when national lobbies dumped $22 million in Washington last year, almost none of it local, to kill a milquetoast but precedent-setting food labeling proposal.

Just three years later, in 1981, the Court barred limits on contributions to ballot measure campaigns as well, in Citizens Against Rent Control/Coalition for Fair Housing v. City of Berkeley. This decision, like its predecessor, ignored other core democratic values, most notably the idea that advantages in the economic realm should not automatically carry over into the political realm—that, indeed, democratic institutions should be carefully insulated from economic power imbalances so that everyone has an equal voice in writing the rules under which we all live. The Court wrote, “The integrity of the political system will be adequately protected if contributors are identified in a public filing revealing the amounts contributed.” Public disclosure, in the Court’s view, is sufficient protection.

Fast forward thirty years to 2011. Previous rulings had affirmed the legality of requiring public disclosure of campaign money and permitted states to ban anonymous gifts, both of which the Northwest states have long done. Ironically, in 2011, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Family PAC v. McKenna that Washington’s exemplary system of public disclosure obviated the need for the state’s precautionary bar on gifts of more than $5,000 during the final days of a campaign. This rule was designed to safeguard the disclosure system from last-minute evasions that might sway an election before voters could ascertain the identities of donors. The court ruled that Washington’s disclosure system was good enough that such subterfuge was unlikely. Family PAC was represented by James Bopp, the Indiana lawyer who launched Citizens United and who has done more than anyone to dismantle American campaign finance rules.

Full Disclosure

Bopp and others, including the Grocery Manufacturers Association that funded Washington’s record-setting No campaign on labeling of genetically engineered foods, are now aiming their legal challenges at disclosure requirements, arguing that revealing the identities of donors places them at risk of harassment. So far, fortunately, the courts have given no quarter. Attacks on disclosure are a major threat in the Northwest, because Oregon and Washington have among the best transparency rules in the United States, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics, which gave both states A-grades last year.

- Oregon: The Beaver State’s sunshine law requires full disclosure through the state’s ORESTAR website of contributions and expenditures related to any measure, and last year, Salem tightened disclosure rules. All campaigns must now report within 48 hours each contribution of $1,000 or more during the last two weeks of a campaign. Independent expenditure campaigns (IEs) must now file electronic campaign finance reports in ORESTAR just like regular campaigns. And everyone has to disclose in-kind contributions.

- Washington: The Evergreen State’s regulations make campaigns promptly itemize contributions over $25, and even the latest-arriving gifts must be reported prior to election day. IEs have to disclose their money, too, and in the last three weeks of a campaign, they must do so within 24 hours. Washington goes further than Oregon by requiring that campaign ads list their five top contributors.

- Idaho: The Gem State requires reporting of most contributions to and spending by ballot measure campaigns, but its system is basic. The National Institute on Money in State Politics gave it a C-grade last year. Idaho’s Secretary of State this year launched the state’s first-ever electronic reporting system for campaigns.

On disclosure, Washington and Oregon could adopt each other’s best ideas, such as Washington’s requirement that ads identify the top donors, a measure also in force in Alaska and California. Idaho would do well to emulate its coastal neighbors generally.

And all three Northwest states could adopt disclosure policies that other states have pioneered. Maryland requires corporations to disclose their political spending to their shareholders. Connecticut instructs corporations making independent expenditures that their CEOs must appear personally in the ads. In Colorado, CEOs need not appear but their contact information must.

Beyond disclosure, the state of Iowa insists that corporations get explicit approval from their boards of directors for each independent expenditure campaign to which they contribute. Legislators in several states, including Montana, have introduced bills akin to Iowa’s, mandating that boards or even shareholders approve political spending.

It’s a bold and fitting principle, really: it demands a modicum of corporate democracy from institutions that want to participate in direct democracy. Not surprisingly, James Bopp challenged this law up to the federal Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. Fortunately, he lost decisively, and the Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal.

Thanks to Jane Harvey, who researched this article.

Tom Lane

Alan,

I agree with you about full disclosure. I-1125, the 2011 Kemper Freeman sponsored citizen initiative to stop light rail from Seattle to Bellevue (among other objectives), is a classic example of millions of dollars in corporate money going to a citizen’s initiative.

In this case, corporations gave to both sides, although it was presumably intended by Kemper Freeman (and probably also Tim Eyman) to be a “citizen’s initiative.” The web site “ballotopedia” lists the major donors and opponents, including Microsoft – (http://ballotpedia.org/Washington_Transportation,_Initiative_1125_(2011).

In 2011, there was very little chance for a fair debate on the viability or constitutionality of light rail on I-90 from Seattle to Bellevue. Therefore, millions of dollars from both sides could have been spend on something that Kemper Freeman has stated that he’s not opposed to – bike lanes. The millions of dollars raised (on both sides) could pay for bike lanes in all of the city limits of Seattle and Bellevue.

It is unfortunate that Washington state elected officials cannot solve the region’s transportation mess, resulting in citizen’s initiatives that result in millions from corporate sponsors, that could be spent on actual infrastructure.

Indeed, in smaller college towns, initiatives on transportation are uncommon, since philanthropic non-profits raise money to clean up garbage, prune trees, and build bike trails.

Mass transit in Seattle is only one example of corporate money, and I-1125 is one of at least three public votes on light rail in the past ten years. How about the recent success of the citizen’s initiative banning GMO crops in Medford and Jackson County, Oregon? Monsanto et. al. were not successful, and the GMO crop seeds were banned. -Tom

Tom Lane

I also do not like politicians and city councils coming out in support or opposition to citizen’s initiatives. With I-1125 (see above), several Washington State elected officials were opposed, including the Governor (as listed on Ballotopedia).

In the case of Palm Springs, California, their City Council spent $58,000 on a campaign discussing raising the sales taxes by 1% for 25 years, for the citizen’s initiative “Measure J” to pave the wide streets, and make many other improvements.

That is a waste of $58,000.

If the Palm Springs City Council needs to raise taxes, why don’t they just vote among themselves to do so, rather than waste $58,000 (not to mention the thousands of dollars to hold the special election). In fact, since Palm Springs had a huge housing crash and resulting financial and infrastructure problems, why don’t they vote among themselves for a sales tax increase that the voters would never go for … 2%? Or, how about 3%? Why not?

See, on ballotopedia, Palm Springs: http://ballotpedia.org/Palm_Springs_Sales_Tax_Increase,_Measure_J_(November_2011) -Tom