Local bans on attached homes in cities are driving up energy use and helping cook the climate, the United Nations Environment Program wrote in a report published Tuesday.

“In some locations, spatial planning prevents the construction of multifamily residences and locks in suburban forms at high social and environmental costs,” the report’s authors wrote. They suggest a 20 percent cut to average floor area per person by 2050.

UN institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have been making similar points for years, usually in more abstract terms like calls for “compact development” or the IPCC’s estimate that even if we can rapidly transition to electric vehicles, we’ll still need to drive about 20 percent less, on average, to bring 2050 carbon emissions down to civilization-preserving levels. (There’s only going to be one way to achieve that: proximity.)

But the passage in Tuesday’s report, spotted by San Jose city planner David Ying, is the first I’m aware of from the UN that acknowledges a major barrier to “compact development”: Apartments and other small attached homes aren’t just necessary. On most North American urban land, they’re also illegal.

Millions of Americans would happily reduce their own carbon emissions by living smaller and closer in, with nicely insulated new windows and nice thick walls, if only local zoning allowed it.

As the UN Environment Program observes, this needs to change as soon as possible.

Six annotated takeaways from the UN’s new climate report

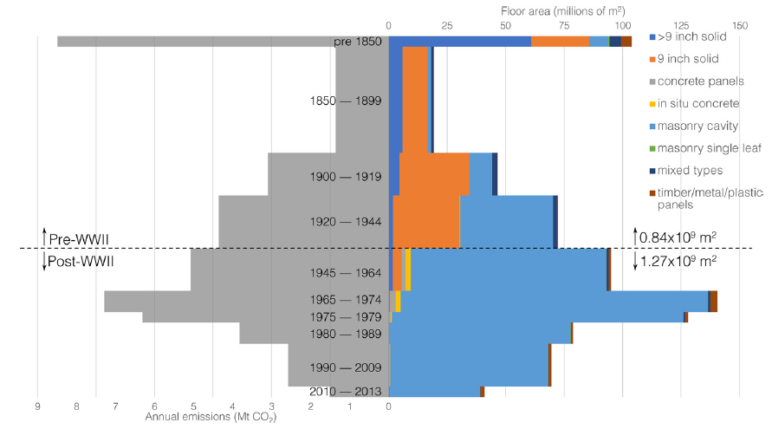

Bigger and older homes = more carbon emissions, as seen in this chart of emissions from English homes. (Aggregate emissions by date built are on the left and aggregate square footage by date built is on the right.) Image courtesy of Cabrera Serrenho et al., Resources, Conservation and Recycling, May 2019. Used with permission.

Tuesday’s UN report reads like, well, a UN report. To tease out the lessons of this key passage on housing, I’ll try to translate the implications into slightly plainer English.

Housing demand tends to increase with a growing income, but varies widely across similar GDP/capita levels, from 34 m2 per person in the United Kingdom to 68 m2 in the United States. Such demand is influenced by tradition, planning rules, tax laws and available space.

Individuals will always have preferences, often for more space. But as a society, we get to choose which options to subsidize and which to ban—and those decisions shape individual choices a lot. Whatever we build today will probably shape culture and behavior for decades.

Multifamily and urban residences tend to be smaller than single family, suburban and rural residences.

The UN says we need to a shift to smaller homes. But why do they have to be attached? What’s stopping you from living in a tiny house with a big yard?

Money. The problem with this plan is that you would need to pay for the land, too—and the price of the land beneath your tiny house is determined by the price of the big house you don’t want. (Because someone who prefers a big house will be bidding against you.) But there’s a simple answer: in places where land is scarce, small homes need to be able to team up. That’s how we invented apartment buildings—and, therefore, cities.

In most countries, the trend is shifting towards a smaller household size, which is leading to an increase in required space as facilities are shared between fewer people.

In 1959, when Portland banned duplexes, triplexes, quads and small apartment buildings from its low-density neighborhoods, the average US household had about 32 percent more people. (Canadian households are a little larger but have been shrinking faster.)

Meanwhile, the average size of a new detached home in the US has nearly doubled, from 1,300 to 2,485 square feet.

Simply put, all those empty rooms are a major waste—of wood and metal, of gas and electricity, and of urban space that could be shared in any of a thousand ways instead of sitting, private but unused, for much of every day and every night.

This is absolutely fascinating. People apparently spend most of their time in common areas/kitchens nowadays. via https://t.co/5HbkzjMUkW pic.twitter.com/hJyHDPoeZD

— Vijay Pandurangan (@vijayp) November 3, 2018

Several studies show that future floor area demand is a crucial variable for GHG emissions and that more intensive use can result in significant reductions of both material and energy related emissions (Serrenho et al. 2019; Cao et al. 2018; Pauliuk et al. 2013).

There’s a reason “reduce” comes first in “reduce, reuse, recycle.” In the housing world, reducing doesn’t have to be bad. It just means living smaller, living closer, living in community.

These lifestyles should at least be an option, but our local laws ban them—sometimes by racist, classist edict and sometimes by a thousand cuts.

Policies that support homeownership may have the undesirable effect of subsidizing large residences through tax breaks and other measures.

Americans (and Oregonians, at the state level) should end the mortgage interest deduction, which mostly subsidizes wealthy people’s decision to own large homes while having no measurable effect on homeownership. There are a million better ways to spend this money.

There is a wide variation in building lifetimes, from less than 25 years in some East Asian countries to more than 100 years in Europe. Extending building lifetimes can therefore have widely different effect. In China, extending the lifespan of buildings to 50 years could reduce CO2 emissions by 400 Mt per year or about 20 per cent of construction-related emissions (Cai et al. 2015). In Europe, new buildings have lower energy use due to improvements in building standards and technology, with lifetime extensions resulting in higher total emissions compared with replacement buildings, unless the building are retrofit to a high energy standard (Serrenho et al. 2019).

Some would-be climate hawks are uneasy about new development because the loss of the old building is seen as a waste. That’s a reasonable concern, but (as confirmed by Serrenho’s study, published in May and cited above) running the numbers tells the other story. In the rich world, where most buildings already last for many decades, further extending the life of old buildings tends to boost emissions, because the overwhelming majority of a home’s lifetime energy use goes toward heating and cooling it, not building it. And newly built homes are far more energy-efficient.

Our leaders need to act

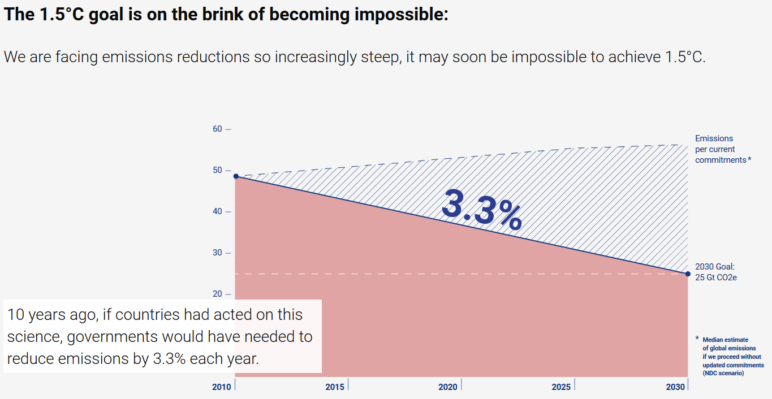

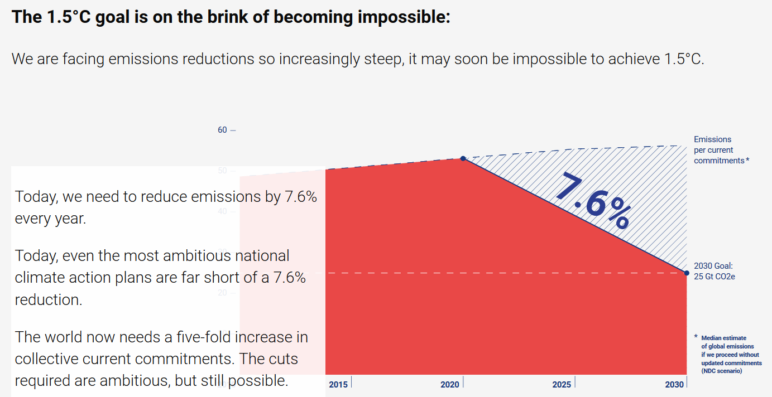

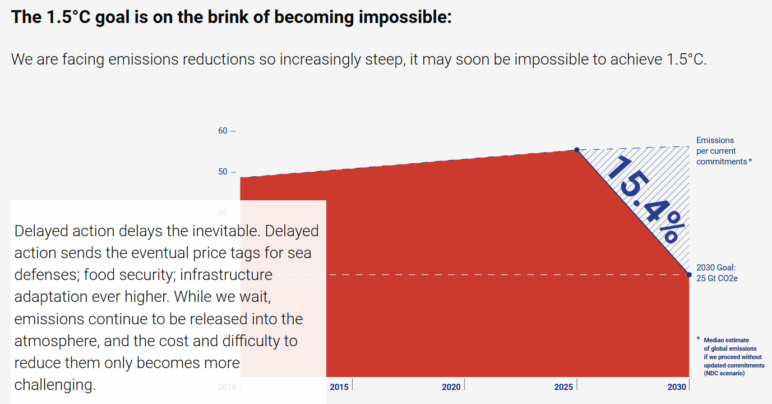

As the generation of humans who stand to witness catastrophic climate change comes of age, policymakers at every level feel moral and electoral pressure to act on climate change.

“Climate activists are not ‘passionate,'” the young climate justice writer Mary Heglar wrote Tuesday. “We are scared for our lives. There’s a world of difference between those two things.”

The website summarizing Tuesday’s UN report hammers that urgency home with a series of charts:

This month, I teamed up with Sara Wright of the Oregon Environmental Council to co-write an op-ed in The Oregonian about the need for cities to allow greener zoning. Amid all our anxiety and anger about climate change, we argued, it can be easy to forget that for many of us, the solutions we need are also the solutions we want.

This month, I teamed up with Sara Wright of the Oregon Environmental Council to co-write an op-ed in The Oregonian about the need for cities to allow greener zoning. Amid all our anxiety and anger about climate change, we argued, it can be easy to forget that for many of us, the solutions we need are also the solutions we want.

We just need to give ourselves permission to live in greener ways.

Our last paragraph came mostly from Sara:

“We can change our cities now, with thoughtful reforms that help people in our community live the way they already want. Or we will all be forced to change our lives later, in haste.”

RDPence

Maybe it’s time to move beyond polemics and begin looking at more details. What are the better ways to rezone SF neighborhoods to allow duplexes, triplexes, etc? If we keep same or similar setback requirements and height limits, we can minimize public opposition~ but would that be workable in practice? The illustration at the top shows a 4-story apartment house with apparently minimal setbacks; maybe OK on an arterial street, but less so in the middle of an existing SF neighborhood.

If we want people to walk to transit and the “corner store,” we needs to have sidewalks. Maybe we allow “-plexes” only in SF neighborhoods with sidewalks, and within a 10-minute walk of good public transit (0.4 miles).

And only slightly off-topic is off-street parking. We’re on the cusp of a boom in electric automobiles, ones that need regular charging, but charging at home requires an off-street parking space where a charging plug can be installed. Maybe we shouldn’t be so quick to eliminate off-street parking requirements for new residential development.

Theo

In my experience, there is no argument that can fully alleviate opposition to duplexes. In my neighborhood, I keep hearing them being blamed for the sidewalk trash and parking congestion. When we went out and discovered that they were not to blame, that did not move the story from people’s minds.

You can dramatically reduce the opposition by classifying additional density as “accessory” to existing zoning. That makes the ownership and financing more difficult, because the accessory units cannot be condominiums, and banks need to get up to speed on how to loan to them, but California’s ADU legalization has led to the creation of several thousands of homes without greenfield sprawl nor infill development battles.

In the medium- to long-term, I think car parking is unfeasible. My SF neighborhood was originally (after ejecting the Ohlone) a working-class neighborhood with small lots and minimal setbacks. We are fortunate enough to have a significant job center, but lots of jobs means lots of housing needs to be added, and it wasn’t. That has led to the country’s worst housing crisis, and my neighborhood was flooded with far more inhabitants than it was built to accommodate. That has fueled the development of ADUs, but there’s no place to put the cars.

It is theoretically possible to rebuild with more parking spaces, and there are a few developments in my neighborhood that are doing so, but (per Donald Shoup) the developments with parking cost so much that they either require millions of dollars in subsidy, or they ignite the wrath of economically backwards community activists. The cars also congest the roads, which are already painfully clogged for much of the day and night. We cannot afford to accommodate the cars.

In the old days, streets did not require sidewalks because the entire street was for pedestrians. Sidewalks are needed for people to walk next to a highway. There’s no good reason to put a highway in a residential neighborhood. If we don’t need a highway, then we don’t need the streets to be wide enough for cars to move smoothly. That frees up lots of space for other priorities, whether light rails or just getting houses closer together. We need systemic change, not electric cars.