UPDATE 3/1/23: The Senate passed SB 5466 on a 40 – 8 vote. The most significant amendment reduced the applicable area around frequent transit stops (at least three stops per hour) from a three-quarter mile walking distance to a half-mile walking distance.

UPDATE 2/23/23: A slightly amended version of the Senate TOD bill, SB 5466, passed out of the Senate Transportation Committee on a 15 – 1 bipartisan vote.

Housing and transit belong together in cities. And this year, Washington lawmakers will take up a bill to help that happen in urban communities throughout the state. If passed, it would be a first for Washington, and the strongest statewide policy of its kind in North America.

The timing is opportune. Last year, Washington passed a transportation funding package that included $3 billion for public transit, by far its biggest investment ever. The state now has a responsibility to get the most out of that investment, and the way to do that is to have more people living and working near transit stops. In urban planning-speak, that’s called transit-oriented development, or TOD.

Sponsored by Senator Marko Liias (D-21), SB 5466 would create flexible standards for cities to allow mid-sized apartment buildings within three-quarters of a mile of transit stops with frequent service, and larger buildings within a quarter-mile of light rail stations. Update: Representative Julia Reed (D- is sponsoring the House companion, HB 1517.

The bill reflects a growing consensus that transit-oriented development is a key solution to the Washington’s massive shortage of housing that’s driving up rents and prices and harming Washingtonians with the least, the most. And this consensus crosses the aisle, even in this era of polarization: Both SB 5466 and HB 1517 have three Republican cosponsors.

A new report from Challenge Seattle, an alliance of business leaders, calls for “[mandating] local jurisdictions to encourage and accelerate [upzoning in] areas near transit hubs to incentivize TOD.”

A new Urban Institute study on transit and zoning in the Puget Sound region concluded that “reforms allowing high-density housing near transit would be most effective overall” to “meet increased demand for housing.”

And that unmet demand for homes is a statewide problem that bleeds across city boundaries, afflicting residents in communities throughout the state, and demanding a state-level response. The best way to add new homes is through the construction of multifamily buildings, and the most sustainable place to put those homes is near transit. And that’s what Washington’s TOD bill would do.

What is transit-oriented development?

TOD is a long-established pillar of urban planning. Think early railroad towns or streetcar suburbs. In more recent decades, cities throughout North America have strived to build housing around new transit investments such as Sound Transit’s Link light rail system. There’s a ginormous inventory of literature on TOD, so I may as well quote from a report I co-wrote in 2009:

New transit investments offer more than a means of moving people from one point to another; they can also be an opportunity to support, and in some cases, create communities by opening up new opportunities for people to gain access to, from, and within the neighborhood. By integrating land use, transportation, and housing policies to foster vibrant and safe mixed-use communities where residents, employees, and visitors can walk, bicycle, or take transit to reach their destinations, cities can continue to grow in a manner that is healthy for both people and the planet.

In 2009, the Washington legislature considered HB 1490, a bill way ahead of its time that included a TOD provision requiring cities to adopt zoning that would allow a housing density of 50 units per acre within a half-mile of light rail stations. (It became a lightning rod for controversy, but the bill died for bigger reasons.) Washington’s only other try on TOD since then was a 2019 bill, SB 5424, that was only intended as a conversation starter and died quickly in committee.

California tried and failed for three years running to pass SB 50, which would have legalized up to six-floor apartment buildings near transit. Though the state did succeed last summer in passing a bill that lifts parking mandates within a half-mile of transit stops.

With its 2021 MBTA Communities zoning law, Massachusetts became the first state to pass strong statewide TOD legislation. The law requires cities and towns to allow multifamily housing around transit stops throughout the Boston metro. Unfortunately, it appears to leave substantial leeway to game the system with zoning changes that wouldn’t actually result in much new housing created. The law is just starting to get implemented, so it’s too soon to assess its impact.

What’s in Washington’s transit-oriented development bill, SB 5466?

Maximum flexibility for cities

Boiled down, Senator Marko Liias’ TOD bill, SB 5466, says that cities must make it possible to construct large buildings near major transit stops. And it’s designed to give local governments maximum flexibility on how they achieve that. It sets a minimum standard for allowing TOD but lets cities tailor the rules to suit the local context.

The bill grants local flexibility in two key ways:

- First, the bill’s building capacity allowances are based on floor-area-ratio, or FAR. More below on FAR, but the gist is that it regulates the overall size, but not the shape, of buildings, and it doesn’t regulate the use of buildings.

- Second, the bill only requires an average allowed FAR near transit. That means a city could opt to restrict selected parts of the TOD area to smaller buildings, as long as it makes up for that with an allowance for larger buildings elsewhere within the TOD area.

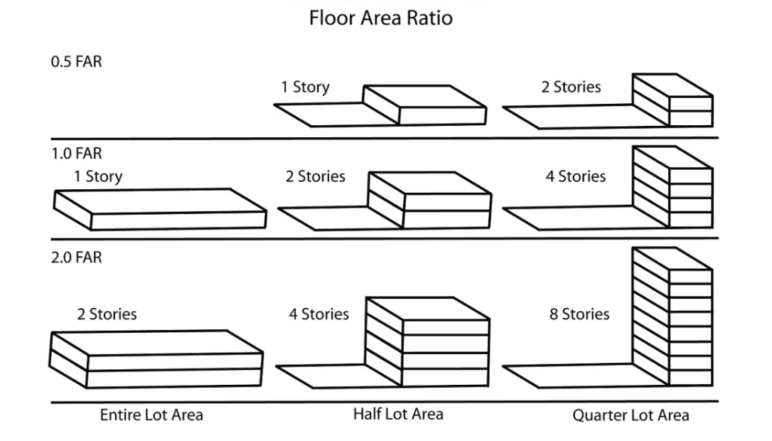

What is floor-area ratio? It’s the total floor area of a building divided by the area of the parcel of land it’s built on. A one-story building that completely covers its lot has a FAR of one. A four-story building that only covers half of its lot has a FAR of two. So the higher the FAR, generally the more homes we’re talking.

You can see how it allows for flexibility in building design: a short, building and a tall, skinny one could both have the same FAR. Local governments could set height limits, for example, to get the building shape that best fits the community.

Another flexible facet of FAR is that it says nothing about the use of the floorspace in the building, leaving the decision to builders or owners. Nor does the TOD bill itself dictate any requirements on use, which is intentional, to flexibly allow a mix of uses that works best for each unique place.

Although the bill’s primary goal is to create housing, jobs are also a strong driver of transit ridership. Not only residential, but also office, retail, and even industrial uses can be appropriate for TOD, and it’s normal for the mix of uses to vary in different station areas (see page 34 of this report for a station area typology).

The TOD bill’s second big flexibility feature is that it allows FAR averaging. That is, the required minimum allowed FAR (we’ll get to that next) applies to the entire station area on average, not to every parcel separately. This gives cities the option to reduce the building intensity in places where that might be appropriate for all sorts of local context reasons, as long as they boost the allowed intensity in enough other places to keep the average allowed FAR at or above the minimum requirement.

Different rules for different distances from transit

So, what does the TOD bill currently in the Washington legislature specifically require for FAR? It establishes two tiers:

- A transit station hub is a quarter-mile radius circle around fixed rail stations. In station hubs, the bill requires a minimum average allowed FAR of 6.0. That FAR is typical for an eight- or nine-story apartment building.

- A transit station area is a three-quarter-mile radius circle around fixed rail stations, bus-rapid transit stations, bus stops with seven-day service, and ferry terminals. In station areas, the bill requires a minimum average allowed FAR of 4.0, which is typical for a five-story apartment building.

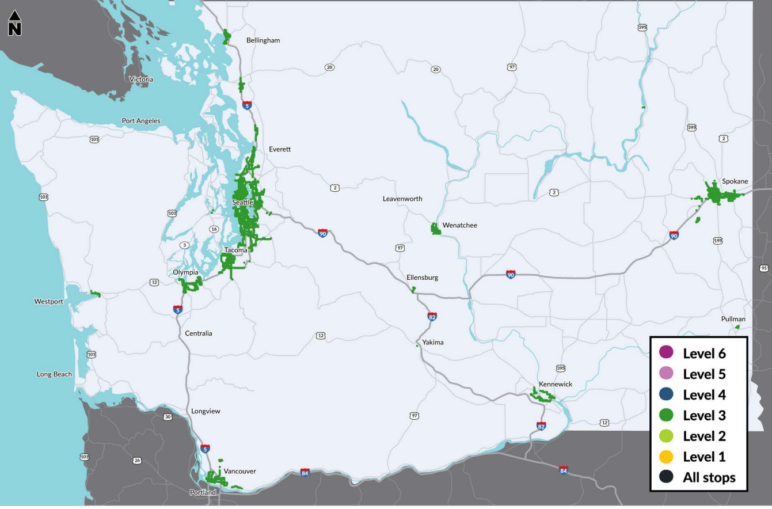

Washington’s Department of Transportation recently published a report that inventories transit stops statewide. The map below shows transit stops meeting their “Level 3” definition of 30-minute service frequency during peak times, and at least 60-minute service seven days week. Though subject to change, that is the TOD bill’s proposed threshold for a “transit station area.”

WSDOT map of transit stops (in green) with “Level 3” service: 30-minute headways at peak times and 60-minute service seven days a week. Image source: WSDOT.

As noted above, the allowed FAR could be lower or higher on lots in different places, as long the average across those lots hits the minimum requirement. The bill prohibits local governments from imposing restrictions such as height limits or setbacks that would make it impossible to construct a real building with the allowed FAR. For a guard rail, it sets a minimum allowed FAR of 1.0 at the individual lot level. And to maximize the creation of new homes, it also prohibits caps on housing unit density.

Releasing builders from onerous parking mandates

The bill’s second critical component for enabling TOD is its removal of parking mandates. It would prohibit local requirements for off-street parking for all building types and uses within the three-quarter-mile radius transit station areas.

Challenge Seattle’s housing affordability report recommends that:

If areas around transit hubs are up-zoned to incentivize development in areas close to cities/job centers, a complementary policy would be to decrease or waive parking requirements, which would reduce construction costs and encourage more development (and drive a positive climate impact through transit-oriented development).

To be clear: the bill would not ban parking. It would only say that developers don’t have to build it if they think their future tenants won’t need it. The intent is to prevent arbitrary government mandates from causing wasteful and costly overbuilding of parking. In North American cities that have ended parking mandates, new housing still usually comes with some parking.

But there’s no better place for ending parking mandates than near transit, because transit makes it easier for residents to meet their daily needs without at car. And that saves them a ton of money, while it also helps the state meet its climate pollution reduction goals (Washington lawmakers will also consider a stand-alone parking bill to lift mandates near transit).

Affordability incentives, technical supports, and other benefits

Other good stuff in the bill:

- To incentivize affordable housing development, the bill offers an automatic 50 percent increase in allowed FAR for housing affordable to people earning 60 percent of area median income (AMI).

- To incentivize child care, small businesses, and three-bedroom homes, the bill excludes building floor area reserved for those uses from FAR limits.

- To protect communities from displacement pressures that could be exacerbated by the bill’s FAR allowances, it would require that cities preemptively take the actions defined by a 2021 bill that established new anti-displacement standards for local planning. Note also that recent academic studies show that constructing new housing has a rent lowering effect within the same neighborhood, and also opens up lower-cost homes in surrounding neighborhoods.

- To help keep land available for affordable housing development, the bill is intended to work in harmony with the Housing Benefit District scheme proposed in HB 1111.

- To incentivize apartment developments that offer 20 percent of their homes at rents affordable to people earning 80 percent of AMI, the bill establishes a competitive grant program.

- To provide support for local governments to implement the bill’s requirements, it instructs WSDOT to create a new program offering technical assistance and planning grants, administered through WSDOT to reinforce the connections between land use and transportation.

- To streamline permitting, the bill exempts from SEPA review most development projects in transit station hubs and transit station areas as long as they are consistent with local comprehensive plans.

What TOD could deliver for Washington

The Urban Institute TOD study noted above projected that loosening zoning within a half-mile of the Puget Sound region’s light rail and bus rapid transit stops could increase the number of homes in those areas “by about 70 percent over the next decade, adding more than 60,000 units compared with the status quo.”

Washington’s TOD bill would require zoning increases at least as big as those considered in the Urban Institute study, and those changes would apply statewide to a greater number of transit stops and larger surrounding areas. So, for a back-of-the-envelope guess, the TOD bill has the potential boost production by a few hundred thousand homes over the next decade or two.

And that’s a few hundred thousand more families and individuals who will be able to find homes they can afford near the jobs and schools and services they love, all across Washington state.

Tom Armstrong

Flexibility? Reads like requirements.

The provision to exempt most development projects in transit station hubs and transit station from SEPA review will be most impactful.

Joseph Farley

In short: Utilize excess capacity in Public Rail Transport Systems (PTS), ( time between trains, part of sunk cost & opportunity cost), for “Trunk-Feeder”, cargo-parcel, trains & trams, contributing line-balancing advantages, not available in any other logistics design. The fixed revenues & huge, positive multiplier effects, will open the doors to cost reductions in many areas, not least of which is reduced break-even, & lower passenger fares, etc….

Required: (a) Refurbished, &/or new, cargo wagons & strategically placed, high-speed transfer points, linking far upstream DCs, hubs, etc. (b) Common Denominator Standardized (ISO) “Feeder RO-RO” carts with (RFID/IoT/AI) options, for ease of handling, linking all points, for optimal, inbound/outbound, B2B, postal, & other bulk replenishments. Recycle can be included in many cases, 24/7.

Concept test see: DHL “Tram parcel deliveries begin in Schwerin.”, Orion High Speed Logistics, UK. Many others…..

Sobrado

This bill looks like a total disaster. First, putting 5 story buildings next to a 1300sq foot 3br entry-level home, just because there is a bus near by doesn’t mean you suddenly don’t need a car for the 8-32 tenants you’ll house next door. You may have to take 3 buses to get to a basic service which isn’t feasible and realistic. So people will just own a car anyway as the only people that can really live without one live in the hyper dense urban core of cities, not in the suburbs. America simply isn’t, and will never be car independent.

Second, half a mile is a crazy long distance to walk to a bus in the poor sidewalked, dark, dangerous PNW which lacks most basic pedestrian infrastructure which will never be developed as there is no funding or requirement to develop it half a mile from said bus stop. The result will be: you guessed it, people buying a car to avoid getting hit by the bus, literally.

Third, transit oriented is nothing more than looking at corridors that have nearby neighborhoods for the purposes of taxation increases due to re-zoning. These neighborhoods are often the cheapest as nobody wants to live near a major road. The result is that the little affordable housing that exists, will be replaced by luxury towers where each unit will cost 2X more than an entry level existing home. This already happened just two blocks from me: a developer bulldozed the woods and build 1.5 million dollar skinny 3 floor dwellings next to homes that have gone for less than 600k. And that’s improving affordability? With taxes going up, I suspect my neighbors will sell, and more 1.5 million dollar homes be replacing what used to be 1st time home buyer homes.

Affordability fail.