The demographics of the Alaska Legislature looked slightly different after the 2022 election. Alaskans sent more Independents to Juneau than ever before. More Millennials won office as the years-long retirement trend among Baby Boomers continued. The share of women legislators held about steady. Racial diversity ticked up modestly.

We wanted to know whether Alaska’s first-time use of open primaries and ranked choice general elections affected any of these demographic changes.* Given the multiple factors involved and the very small sample size of one set of election results, the job seemed futile. The exceptionality of 2022 showed itself early with the unexpected death of Alaska’s longest-serving Congressman, and it persisted for reasons other than the debut of Alaska’s election system. The 10-year redistricting process reshaped legislative boundaries and put 19 of 20 Senate seats, along with all House seats, on the ballot (normally, Senators serve staggered 4-year terms and House members serve 2-year terms). The open seat in Congress triggered a special election. And a record number of incumbents chose not to run again. Attributing all the new faces and dynamics in Juneau to the election system would overlook these and a host of other factors that influenced who ran and how voters made their selections.

Still, we decided to check out the data. We found open primaries combined with the ranked choice general election most obviously influenced political diversity in the legislature. But when it came to age, gender, and race, nationwide demographic shifts toward greater diversity that predated the system appeared to exert more significant effects. The system probably didn’t do much to improve diversity in these cases but also did not appear to disrupt preexisting trends. Nor did it significantly alter the Independent/right-leaning dynamic of the House and the Senate. Its virtue lay in providing Alaska’s many Independent-minded voters a way to express their nuanced, non-binary political views.

How we did our analysis

To measure diversity in the Alaska legislature, we gathered data in four demographic categories tracked by the National Council of State Legislatures. They were political party, age, gender, and race. We then analyzed legislative classes from 2008 to 2022 and the factors most likely to have shaped their demographic makeup, including the following:

- The debut of Alaska’s voter-approved election system of open primaries and ranked choice voting;

- New political boundaries from the latest round of redistricting changing the constituencies of some seats;

- An unusually high number of veteran legislators choosing not to run for a variety of reasons (e.g., family considerations, health issues), making way for an unusually large freshman class;

- Normal generational turnover;

- Shifts in political culture and societal norms;

- Quality of candidates and campaigns; and

- Buzzworthiness of candidates at the top of the ticket.

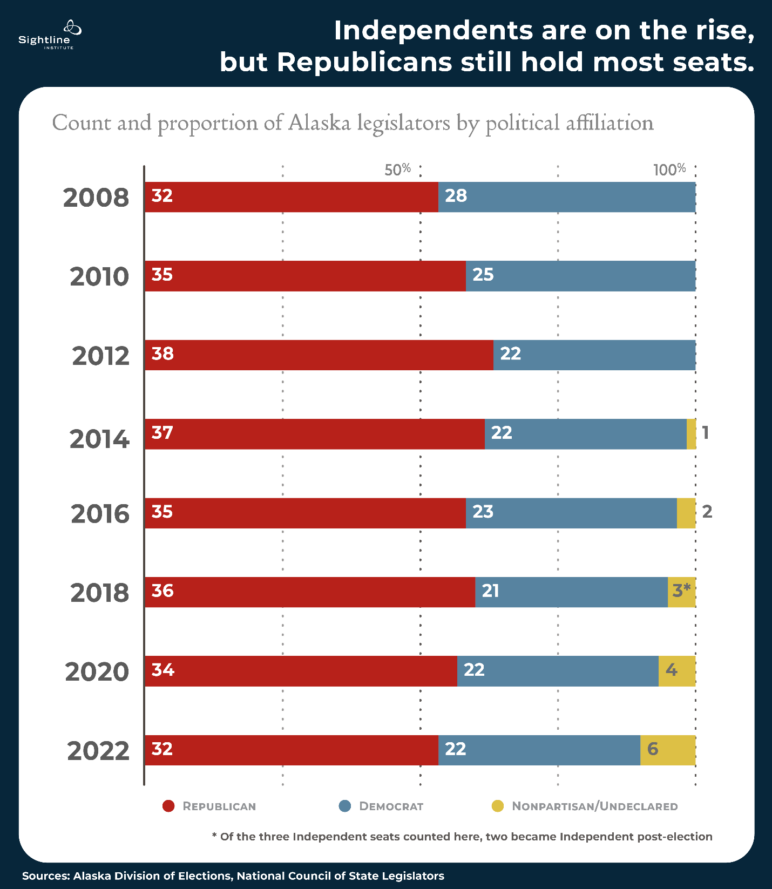

Independents have more representation than ever

More Independents serve in the Alaska legislature today than at any point in the state’s history, with six members of the House eschewing party labels. The growth in representation by Independents did not meaningfully alter the longstanding political order. In both chambers, Republicans maintained the majority they’ve held since the 1990s, and no Independents won seats in the Senate.

Nearly 60 percent of Alaska voters are Independents, meaning they self-identified as “nonpartisan” or “undeclared” or opted not to choose any political affiliation when signing up to vote.1 The Independent identity of Alaska voters takes many forms: the pro-oil development Democrat is no anomaly here; nor is the Republican pushing to spend billions in state budget dollars on the Permanent Fund Dividend (or the “PFD,” which researchers from the University of Chicago and elsewhere have studied as a form of universal basic income, a concept with socialist roots).

And yet, until 2022, Independent representation in the legislature never broke single-digit percentages. The advent of open primaries, which allowed all candidates and all voters to participate in a single primary, regardless of party, did away with election laws that were stacked against candidates outside the two major parties. And ranked choice general elections gave Independents the leeway to run with little risk of becoming the “spoiler” candidate. The new system, more than any other factor, was the most obvious game-changer for political diversity in the Alaska legislature.

Before 2022, political parties ran Alaska’s primary elections and tended to treat Independents as second-class candidates. The Republican party barred Independents from its primaries entirely, and so did Democrats until 2018. In those years, Independent candidates wanting to run in a primary had to give up their political identity by registering with the party running the primary they wanted to enter. Maintaining their Independent brand meant missing out on the primaries and having to gather enough signatures to qualify for the general election ballot.

Former Representative Paul Seaton (Homer) was a longtime Republican legislator. In 2018 he ran as a nonpartisan candidate because, he said, he felt the party “had gone off track and was not working on solutions.” In the previous session, as co-chair of the House Finance committee, Seaton had angered a panoply of voters because of his work to shield Alaska’s budget from the booms and busts of the oil market by diversifying sources of revenue. He annoyed a large cross-section of constituents, including those who opposed a fiscal plan that would have increased taxes on oil companies, introduced a state income tax, and reduced the PFD.

“There was the Republican primary and the everybody else primary, and I ran in the everybody else primary.” –Former Alaska State Rep. Paul Seaton

Seaton’s stance on state budgeting put him at a disadvantage, but so did Alaska’s election laws, which obfuscated his identity as an Independent. Democrats allowed third party candidates and Independents into their primaries that year, while Republicans did not. If Seaton wanted to participate in a primary, he had to go on the Democratic ballot. “There was the Republican primary and the everybody else primary, and I ran in the everybody else primary,” Seaton said.

He ran unopposed in the primary and went on to face a Republican in the general, where ballot labeling presented another hurdle for Independents. Seaton had an (N) for “nonpartisan” next to his name, along with the far more prominent label of “Alaska Democratic Party Nominee,” determined by the Division of Elections. (Pre-open primary, the division’s choice of ballot labels was a contentious issue.) Though Seaton had been a Republican for 50 years, voters in his district, where former President Donald Trump won easily in 2016, could be excused for thinking he had switched parties. Unsurprisingly, Seaton lost the seat he had held since 2003.

A few Independent legislators nonetheless managed to win elected office under the old system, starting with Rep. Dan Ortiz (Ketchikan) in 2014. Since then, their numbers have remained so low that name-checking all of them isn’t a huge stretch: Rep. Jason Grenn (Anchorage) ran successfully as an Independent in 2016, joining Ortiz in the House. Grenn then lost in 2018, while Ortiz won.

(In 2019, two former Democrats, longtime legislator Bryce Edgmon (Dillingham) and John Lincoln (Kotzebue) changed their party affiliations to undeclared while serving in the legislature. Though they did not actually run for office as Independents, they are included in the chart below.)

In the election years we analyzed, Ortiz and Grenn were the only Independents to run and win until 2020, the first year candidates had ample prep time to run in the Democratic primary. Even then the numbers were modest, with four Independent legislators winning office. Two of them, Edgmon and Calvin Schrage (Anchorage) ran in the Democratic primaries. Ortiz and Josiah Patkotak, a right-leaning Independent, appeared on the general election ballot only.

In 2022, Alaska voters returned to open primaries and, for the first time, used ranked choice voting in the general election. Open primaries, where all candidates of all political affiliations run on a standard ballot accessible to all voters, equalized the playing field for Independents. Electoral reforms that lowered barriers for candidates and voters outside the major parties appear to be the likeliest explanation for the record high number of legislative Independents. The previous round of redistricting a decade ago did little to change the political diversification of the legislature. And Independents have been a large voting bloc in Alaska for years. The new system finally gave them a real chance to run and win.

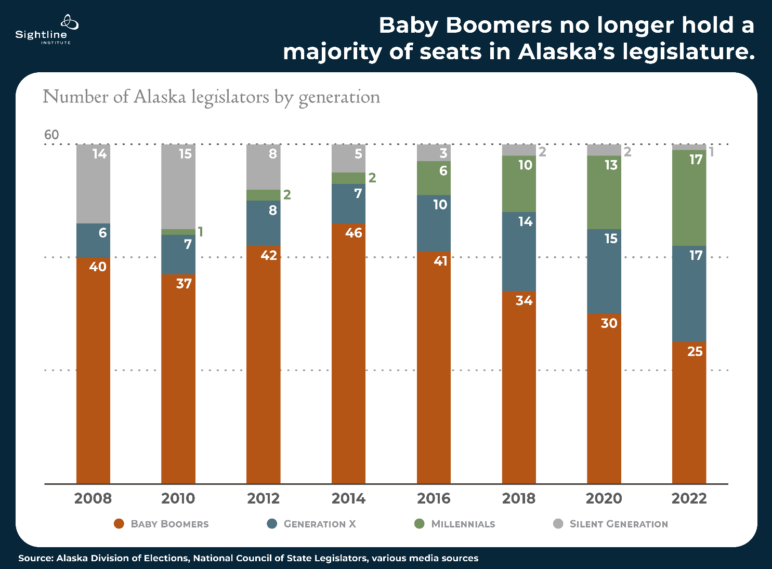

Millennials gained and Boomers waned (but remain powerful)

Generational diversity in Juneau hit a low in 2014, when Boomers held 46 of the legislature’s 60 seats. Since then, the number of Boomers has declined every election, and an influx of Generation Xers and Millennials has led to more age diversity in the legislature.2 In 2014, two Millennials served in the legislature. In 2022 voters sent 17 Millennials to Juneau and Boomers made up less than half the legislature for the first time during the eight legislative sessions we examined.

The gradual exit of Boomers masks the fact that they continue to win an outsized number of seats relative to their share of the population. In 2020, for example, Boomers won half the seats in the Senate and House combined, while making up just 28 percent of Alaska’s voting age population, according to American Community Survey data from the US Census. This isn’t surprising. Older lawmakers with years of experience have had ample opportunity to accumulate the connections, institutional knowledge, and seniority that afford them staying power.

Alaska isn’t the only political body where Boomers hold disproportionate sway. In the US Congress, the median age in 2023 is higher than it’s ever been. And Boomers are a large cause for the increase. Boomers won 48 percent of seats in the current Congress, while making up about 21 percent of the general population.

Natural aging of the population seems the likeliest cause of changes in generational makeup of the Alaska legislature. The steady drop in the number of Boomers began in 2016, well before open primaries and ranked choice voting went into place and several years before the COVID-19 pandemic kicked off a nationwide retirement boomlet. An unusually high attrition rate among incumbents due to redistricting, burnout, family obligations, pandemic stress, and the financial demands of maintaining a second household in Juneau, created more opportunities for new lawmakers to win office but didn’t noticeably alter the overall rate of generational transition.

Open primaries and a ranked choice general election appeared to have little positive or negative effect on generational succession. Running for office is a daunting undertaking for younger candidates who lack the political experience, financial backing, and networks necessary to run a successful campaign. Youth-oriented political action committees, role models, and targeted encouragement may prove more effective than the election system in boosting the number of Millennials and Gen Zers holding political office.

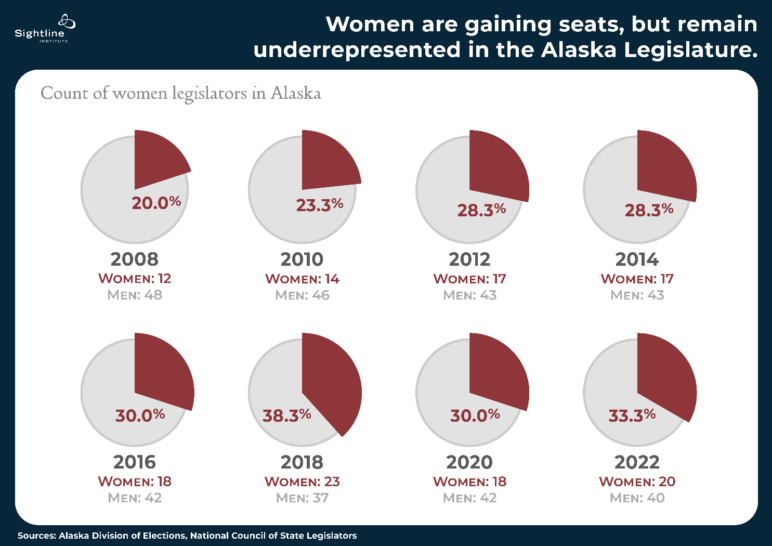

Women need more than electoral reforms to win

An enduring but incorrect Alaska stereotype is that men vastly outnumber women. That’s certainly the case in the Alaska legislature, where just one-third of lawmakers who won office in 2022 were women. But among registered voters, the ratio of men to women is nearly equivalent. In October 2022, 49 percent were women and the rest were men.

Open primaries and ranked choice voting didn’t appear to influence or alter the gradual, years-long trend of more Alaska women winning legislative seats. The presence of women lawmakers in Juneau has grown steadily over the past 8 election cycles. From 2008 through 2014, women never won more than about 28 percent of seats in the legislature. From 2016 through 2022, women have held at least 30 percent of seats.

Nationwide, more women have moved into powerful political roles, regardless of the type of election they’re running in. The number of women in Congress is at a historic high, according to a report in October by the Congressional Research Service. And women have made political gains elsewhere: the vice presidency, the president’s cabinet, governorships, mayor’s offices, and city councils. Two of the three members of Alaska’s Congressional delegation are women, with voters sending Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski, Alaska’s senior senator, and Democratic Rep. Mary Peltola, a House freshman, to Congress in 2022. “There’s no clear narrative” as to why women are making gains, according to Kelly Dittmar, director of research at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

Alaska has a higher percentage of women in its legislature than Congress does, but among state legislatures, its record of electing women is exactly average, ranking 25th in 2023. Fourteen states and territories have over 40 percent of their legislatures represented by women, while Alaska’s legislature is 33 percent women, according to the Center for American Women and Politics.

The share of women in the Alaska legislature representing both major parties is identical, with nine Republicans, nine Democrats, and two Independents. A woman, Rep. Cathy Tilton, a Republican, is House Speaker. Sen. Cathy Giessel, also a Republican, is Senate Majority Leader of a bipartisan majority that includes all but three senators. Data shared by Glenn Wright, associate political science professor at the University of Alaska Southeast, shows a decade-long trend in the Alaska legislature of Republicans fielding the higher intra-party percentage of women. In 2020 and 2022, however, Democrats reclaimed the top spot.3

Women are underrepresented in US politics for all sorts of reasons, from sexism in media coverage of politicians to sexism on the campaign trail to sexism in state legislatures. A RepresentWomen study posited that ranked choice voting makes elections more women-friendly by reducing concerns over vote-splitting between women candidates, incentivizing more cooperation between candidates, and lowering the financial barriers for all candidates. More equitable election policies can help, but other changes, targeting barriers from the psychological to inadequate support for raising a family, are also necessary.

Men are 40 percent more likely than women to field suggestions to run from close contacts, including colleagues, spouses, or family members. And men are two-thirds more likely than women to receive encouragement to seek office by an elected official, party leader, or political activist according to a 2022 report by the Brookings Institution.

“Potential candidates’ self-perceptions are consistent with messages they receive—or don’t—about running for office,” the report said. “Still today, we operate in a world where people see men as candidates. And men see themselves that way. Significantly fewer women live in that world.”

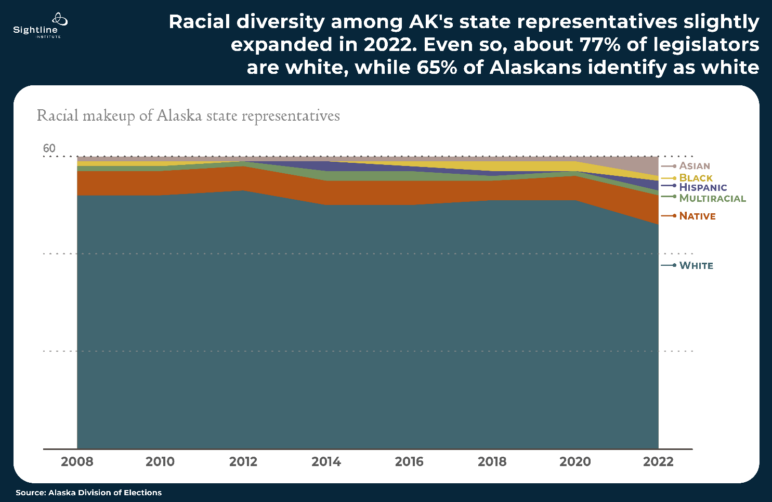

The Alaska legislature is more racially diverse than ever

Of the eight election cycles we analyzed, voters sent the most racially diverse group of lawmakers to Juneau in 2022.4 Six identify as Alaska Native, three are Black, two are Asian, two are Hispanic, and one is Multiracial. They come from across the state: Southeast Alaska; Anchorage; the North Slope hub community of Utqiagvik; and Dillingham, in Southwest Alaska.

Legislators of color tend to be Democrats, underscoring Republicans’ lower success in expanding the racial diversity of their candidates. The trend occurs nationwide. While the GOP added more people of color in Congress, it still lags Democrats. In Congress, 80 percent of lawmakers of color are Democrats, while 20 percent are Republicans. Similarly, in Alaska, two lawmakers of color are Independents, three are Republicans, and eight are Democrats. Two of the three Republican legislators are Black. Both Independents are Alaska Native, with one leaning left and the other leaning right.

White politicians still make up an outsized majority of Alaska legislators, holding 77 percent of seats while whites make up about 65 percent of the population. Alaska Natives remain underrepresented. They make up close to 20 percent of the voting age population, according to Alaska Native voting advocacy groups, but hold only 10 percent of legislative seats. Still, that 10 percent marks a high point in the eight election cycles we analyzed for Native representation in the legislature.

Open primaries and ranked choice voting coincided with the election of the most racially diverse class of legislators in the years we analyzed. While demographic change seems a highly likely reason for the increase in racial diversity in Alaska’s legislature, it doesn’t explain everything.

True, younger generations in America are more diverse than older ones. And, as we explained above, Millennials appear to be replacing Boomers. This would seem to indicate that racial diversity is somehow tied to generational succession. And yet, until 2022, racial diversity in Alaska’s legislature remained essentially flat during the years we studied, even as the number of Boomer legislators decreased and Gen Xers and Millennials took their places.

Does that mean open primaries and ranked choice voting in Alaska did somehow open the door for candidates of color? Possibly. But there’s also the marked shift in the way Americans view race that began during the pandemic with the police murder in 2020 of George Floyd. Political participation by people of color increased as a result. What’s more, across the country, states with election systems different from Alaska’s, including California,5 Oregon, and Minnesota, also elected their most diverse legislatures ever in 2022. We expect additional elections will offer a more complete picture.

For better or worse, Alaska’s legislature hasn’t changed dramatically

Alaska has had only one election using open primaries and ranked choice voting, and it appears to have had positive to neutral effects on four of the main markers of diversity tracked by the National Council of State Legislatures. While some may feel disappointed that the system didn’t cause a dramatic uptick in diversity, incremental change did occur. The system advanced political diversity by allowing more Independents to run; and it didn’t interfere with natural generational change, didn’t appear to help or hurt women, and possibly played a role in more seats being won by people of color.

Is the legislature as diverse as it should be? Probably not. Boomers still hold an outsized influence, both in numbers and power, relative to their share of the population. (Podcaster Andrew Halcro, himself a Boomer, goes so far as to label these legislators the “tyrannical generation.”) Women continue to be vastly underrepresented. And so do people of color.

On the other hand, the legislature does accurately reflect Alaska’s Independent/right-leaning politics. Anyone arguing that the system was rigged to send a wildly different cohort of lawmakers to Juneau has only to look at the makeup of the two chambers. The state Senate has a 17-member bipartisan majority and appears to be making good on its promise of “compromise and consensus.” Meanwhile, the House shifted rightward, veering into the tumult that has come to define some branches of the Republican party. The dynamic of the two chambers is a mirror image of Alaska’s most recent legislatures, where the House had a bipartisan majority and the Senate leaned conservative.

Are they still haggling over the Permanent Fund Dividend? Yup. Are culture wars over sexual orientation and gender still a thing? Yes. Are school budget talks still hugely difficult and sticky? Absolutely. All this is to say Alaska’s legislature didn’t undergo massive change in 2022 when it came down to the business of lawmaking. But by choosing open primaries and a ranked choice general election, Alaskans gave themselves a more democratic method than they’ve ever had of picking the people for the job.

Thanks to Nakeshia Diop for collecting the copious amounts of data that are the heart of this article.