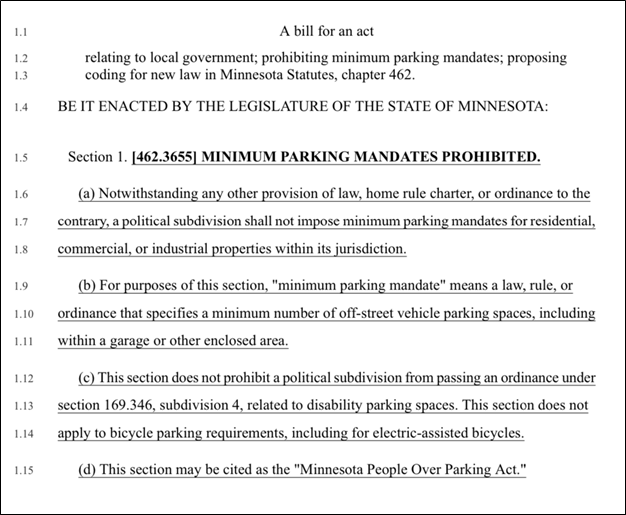

Washington state leaders set out again this legislative session to move the state’s utilities forward on a path toward electrification and away from gas. House Bill 1589—a bill that passed in the 2024 session and is to be delivered to Governor Jay Inslee’s desk any day now—is a move in that direction.

This bill, initiated by Puget Sound Energy (PSE), Washington’s largest electric and gas utility, requires the utility to proactively plan for the transition from gas to clean energy. The coalition of climate and consumer advocates who helped usher it to passage knew that to get PSE to retire its existing gas infrastructure, the bill would have to include sweeteners for the utility, likely in the form of financial benefits to be paid by ratepayers.

However, the final version of the bill, as amended during this year’s legislative session, overplays the PSE incentives piece, upsetting a delicate balance between climate benefits, ratepayer protections, and enticements for the utility. Further, overly generous financial boons to PSE could hamper the state’s future negotiating power with the utility on important, additional decarbonization moves.

The two outsized financial benefits to PSE include accelerated depreciation (Section 7) and earnings on large electric projects still in construction (Section 5.2.d). These upsides for PSE are set to become law by the end of March 2024, but Governor Inslee could rebalance this bill in the next few days, using his veto authority to remove specific sections.

Below we outline what’s good about the bill and what needs to be cut in order to retain the spirit of the original decarbonization solution—balancing perks for PSE with the provisions that step the utility toward a thoughtful and systematic transition to clean energy—and away from fossil fuels—keeping on track with the state’s climate commitments.

A critical step toward decarbonization: HB 1589 reinforces Washington’s climate priorities

This bill goes a long way toward putting PSE on a path toward decarbonization—an essential piece in Washington’s carbon emissions puzzle if the state is to meet its 2050 goals. In particular, Section 3 of the bill calls for PSE to undertake comprehensive decarbonization planning.

The policy sets up an entirely new planning framework for the utility, folding together most of its existing planning requirements on both the gas and electric sides of its business into a single integrated system plan and orchestrating a holistic approach that prioritizes substantive decarbonization. Here are the most important planning updates that the bill puts in motion:

- Sets up expansive new electrification programs to help transition PSE customers off gas

- Drives PSE to assess potential to electrify entire neighborhoods as an alternative to aging pipeline replacement and as an opportunity to decommission sections of the gas system

- Requires PSE to evaluate a suite of alternatives to additional investment in the gas pipeline system

- Increases the annual commitments for electricity conservation and demand response to offset some of the expected new electric loads

The utility receives cash from auctioning off its carbon allowances in the state’s carbon market. HB 1589 reaffirms a provision in the Climate Commitment Act to prioritize this cash to support low–income families with bill assistance, non-volumetric bill credits, and electrification programs. The bill directs PSE to use the remaining funds towards programs to help residential and small commercial customers electrify in lieu of the non-volumetric bill credits that nearly all PSE customers are receiving today.

Veto the accelerated depreciation provision to rebalance the climate upsides with the financial perks for PSE

Buried deep in a section in HB 1589 is a provision called “accelerated depreciation.” Accelerated depreciation (AD) would ramp up the repayment rate for PSE’s long-lived gas infrastructure so that the utility could recover its investments sooner—ideally, before 2050 when the state’s emissions targets call for a 95 percent reduction in carbon pollution from gas.

This AD provision, offered as an enticement to PSE in exchange for unwinding its gas business, might have made sense when the bill still contained its original provisions to end new gas connections and allow PSE to decommission and retire gas pipelines. However, those parts were negotiated out of the bill over the course of the legislative session.

The final package passed this month is therefore lopsided, with too many financial perks for PSE and too few financial solutions for managing the costs of the gas-to-clean-energy transition for consumers. Governor Inslee has the power to help correct this imbalance. Sightline recommends that the Governor veto Section 7 of the bill, which would remove the provision for PSE to accelerate the recovery of its investments in gas assets.

Accelerated depreciation, on its own, can’t support the decarbonization transition; it needs complementary policies

Managing the energy transition means choosing a strategy that achieves the state’s decarbonization goals while minimizing costs overall for ratepayers and shielding the lowest-income households from bearing those costs. If left unmanaged, the ongoing costs of the expansive pipeline system will be spread over a shrinking number of gas customers, resulting in sky-high gas rates for those remaining, likely low-income homeowners and renters.

Decarbonization thought leaders have proposed a suite of policies that could work together to lessen the financial impacts on consumers as their utilities transition away from gas. Policies like ending gas pipeline expansion, electrifying as an alternative to replacing aging or leak-prone pipelines, and modifying gas utility’s “obligation to serve” all work together to avoid growing the piles of cash invested in gas pipelines. Meanwhile, policy and regulatory tools such as securitization, accelerated depreciation, adjusting rate cost allocations, changes to utility profit rates, and using external funding sources to recover gas transition costs can support the utility and state in managing the sunk costs of the energy transition.

But none of these policies is adequate on its own. The state’s lawmakers and regulators must join these policies with one another to effectively manage the energy transition. Some of these policies, like accelerated depreciation, raise rates for gas consumers. To balance this, securitization can refinance the borrowing costs of the rate base. So together, these policies can stabilize rates while reducing the risk of stranded assets. In a similar way, ending new gas connections while also allowing electrification to satisfy a gas utility’s obligation to serve complement one another: together, they let the utility start to shrink its infrastructure footprint, leading to reduced operations and maintenance costs.

Unfortunately, HB 1589 only offers the accelerated depreciation policy, absent complementary policies that could minimize rate impacts, especially for low-income households. The bill emphasizes electrification but continues to allow gas system expansion and avoids the key policy needed to shrink the gas system: changes to the gas utility’s “obligation to serve.” In doing so, the bill fails to advance the interlocking tools needed to effectively manage the energy transition. Granting PSE accelerated depreciation, a tool for minimizing stranded asset risk, without having a strategy for how to handle the financial impact of a declining number of gas ratepayers during the transition, could dissuade both PSE and legislators from coming back to the table to work on this critical issue.

The legislature must create a plan for PSE to end gas hookups, end the “obligation to serve,” retire pipeline assets to remove them from customers’ bills, and look at other funding sources to help cover the future rising costs of gas, especially for low- and moderate-income households and tenants—and all of this prior to adopting accelerated depreciation.

Implications of accelerated depreciation: Higher gas bills

Section 7 of HB 1589 mandates that regulators approve accelerated depreciation schedules for PSE’s existing gas assets. Gas pipeline assets are long-lived: a new gas main is estimated to have a 60-year life, with repayment schedules extending out as far as 2084. Few, if any, gas customers will remain to pay off the residual value of that gas main past 2050, possibly denying PSE’s shareholders their approved returns.

House Bill 1589 removes this incongruity for gas assets in service by July 1, 2024, and requires PSE to accelerate the rate at which its shareholders are paid back, so that it is by 2050 or sooner. At the same time, for assets that would otherwise be fully recouped before 2050, it allows the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission to stretch out the shareholders’ recovery period to 2050, to help temper rate impacts. For gas assets put into service after this summer—and PSE is planning to invest $416 million in just 2025–2026, according to its general rate case—HB 1589 fails to lay out a strategy on how the rate recovery for those assets will be handled. Presumably, the new decarbonization plans that PSE drafts will prescribe much less spending on pipelines, but its first plan isn’t due to the WUTC until 2027, more than 2.5 years away.

Shortening the depreciation period on younger assets increases near-term costs for consumers. In the long run, consumers pay much less overall, saving on payments for profit and taxes over the longer depreciation term. The concept is like a 15-year versus a 30-year mortgage, where the borrower pays much less interest over the life of the 15-year loan but has higher monthly payments than the 30-year loan. Still, most homeowners choose 30-year mortgages because the monthly payments are more affordable.

PSE’s 2024 general rate case, filed in February, requests accelerated depreciation for its gas assets and forecasts how various AD rates would affect depreciation expense. WUTC regulators can authorize accelerated depreciation without a change to the law, but under HB 1589, lawmakers have essentially overruled the WUTC’s authority. This sets a precedent that could invite utilities to argue their rate cases before the legislature instead of using the adjudicated process followed by regulators.

According to PSE’s filing, recovering the full value of all existing gas assets on or before 2050 would push the annual depreciation expense 52 percent higher than current levels. The filing does not provide an analysis of impacts to profits or taxes, nor does it contemplate extending depreciation lives as HB 1589 would allow.

To examine the impacts of both depreciation and profits, Sightline performed a similar analysis, modeling the full depreciation of all assets by 2050 but stretching out some asset lives to 2050 to moderate the rate impacts. With accelerated depreciation over the course of 2024–2049, customers would pay an extra $199 million over status quo. Overall, examining the time horizon 2024–2085, when all assets as of 2023 would be fully paid off under the status quo approach, customers could save $501 million in avoided profit.

| Total 2024-2049 | Total 2024-2085 | |

|---|---|---|

| Depreciation Expense and Profit (Status quo) | $11,059,995,523 | $11,760,567,683 |

| Depreciation Expense and Profit (Accelerated depreciation) | $11,259,257,036 | $11,259,257,036 |

Ultimately, the accelerated depreciation provision, as currently laid out in HB 1589, removes substantial risk for PSE’s investors. The utility has $6.1 billion of future depreciation expense on its books, and AD guarantees that investors will see their expected returns.

But the provision fails to balance the risks to ratepayers versus shareholders, especially in terms of protections for low-income ratepayers. It also ties the hands of the WUTC to throw out unfair accelerated depreciation proposals.

What to keep? Section 5: Early earnings on large electric projects transfers risk but supports rapid buildout of renewable electricity and transmission

Another area of House Bill 1589 deserving attention is its “construction work in progress” (CWIP) provision. CWIP would be a new accounting method applied to the construction of large, new electric projects that would transfer some of the investment risk from investors to ratepayers. CWIP is tangentially related to the package of policies needed to manage the energy transition because it provides better cash flow to PSE, which could in turn support more aggressive construction schedules for electric infrastructure needed as the state ditches gas. Importantly, though, it could still cost ratepayers less overall than the accounting method used today, called “allowance for funds used during construction” (AFUDC).

Let’s compare what the bill would do as written to the status quo. Under the status quo AFUDC, PSE puts all its construction expenses on a big credit card that amasses compounded interest for the duration of the construction period. Once the project is in service, customers start paying off that credit card’s balance. At that point, five years or more down the road, the debt is much larger because of the compounded interest charges.

The bill’s added CWIP option, in contrast, is written to allow ratepayers to avoid some of those financing costs by paying off some of that debt on very large electric projects that are still under construction (not yet in service)—like making the minimum payment on one’s credit card. The utility benefits because PSE earns both a profit on those payments much sooner than it would under the status quo and it has more cash on hand to redeploy for other projects. Regulators in California have raised concerns that these profit earnings on CWIP—the projects still under construction—can drive up customer rates when projects take longer than planned or costs escalate beyond initial forecasts.

The CWIP provision in Washington’s HB 1589 is limited to electric projects like renewable energy generators and transmission lines costing more than $100 million with a project schedule greater than five years—precisely the kinds of projects that will help bring Washington the clean electricity it needs to decarbonize its economy. At its discretion, the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission can deny this alternative accounting method and maintains its authority to disallow rate recovery of expenses (regardless of accounting method) if they are found to be imprudent. For these reasons, Sightline supports retaining section 5, which offers an alternative accounting method for regulators to consider using.

With an eye to the long game and leverage, Governor Inslee can improve this bill—and his climate legacy—with a single section veto

House Bill 1589 charts a direction for Washington’s largest gas company to decarbonize its operations in line with the state’s climate and clean energy transition commitments.

The decarbonization approach in Section 3 is sound: transition customers’ combustion appliances to high-efficiency electric alternatives like heat pumps, and aggressively pursue energy conservation and demand response to forego the need for new resources and to draw down emissions.

But this bill has a concerning provision that could burden the company’s gas customers with higher bills, absent complementary policies: accelerated depreciation. And while the initial bill that PSE proposed had several additional decarbonization principles that might have sufficiently warranted the accelerated depreciation giveaway to PSE, the version of HB 1589 that passed, lacks complementary policies for leveraging accelerated depreciation to its full potential—to meet decarbonization goals and to protect Washington ratepayers.

Lawmakers and gas utilities in the state need to put a comprehensive financial package together, including the use of accelerated depreciation, to support Washington families during the transition. Until that full package emerges, Sightline recommends that Governor Inslee veto Section 7 to rebalance the bill’s decarbonization upsides by removing the mandate of accelerated depreciation.

This article was updated on 3/15/24. A previous version stated that HB 1589 would prioritize funds received from the state’s carbon market for low-income families. We have updated the article to reflect that this policy is already law under Washington’s Carbon Commitment Act and that HB 1589 only reaffirms this policy.