Editor’s note: This is the third of three articles discussing the major challenges—planning, paying for it, and permitting—to building the transmission lines needed to transition to a cleaner energy future.

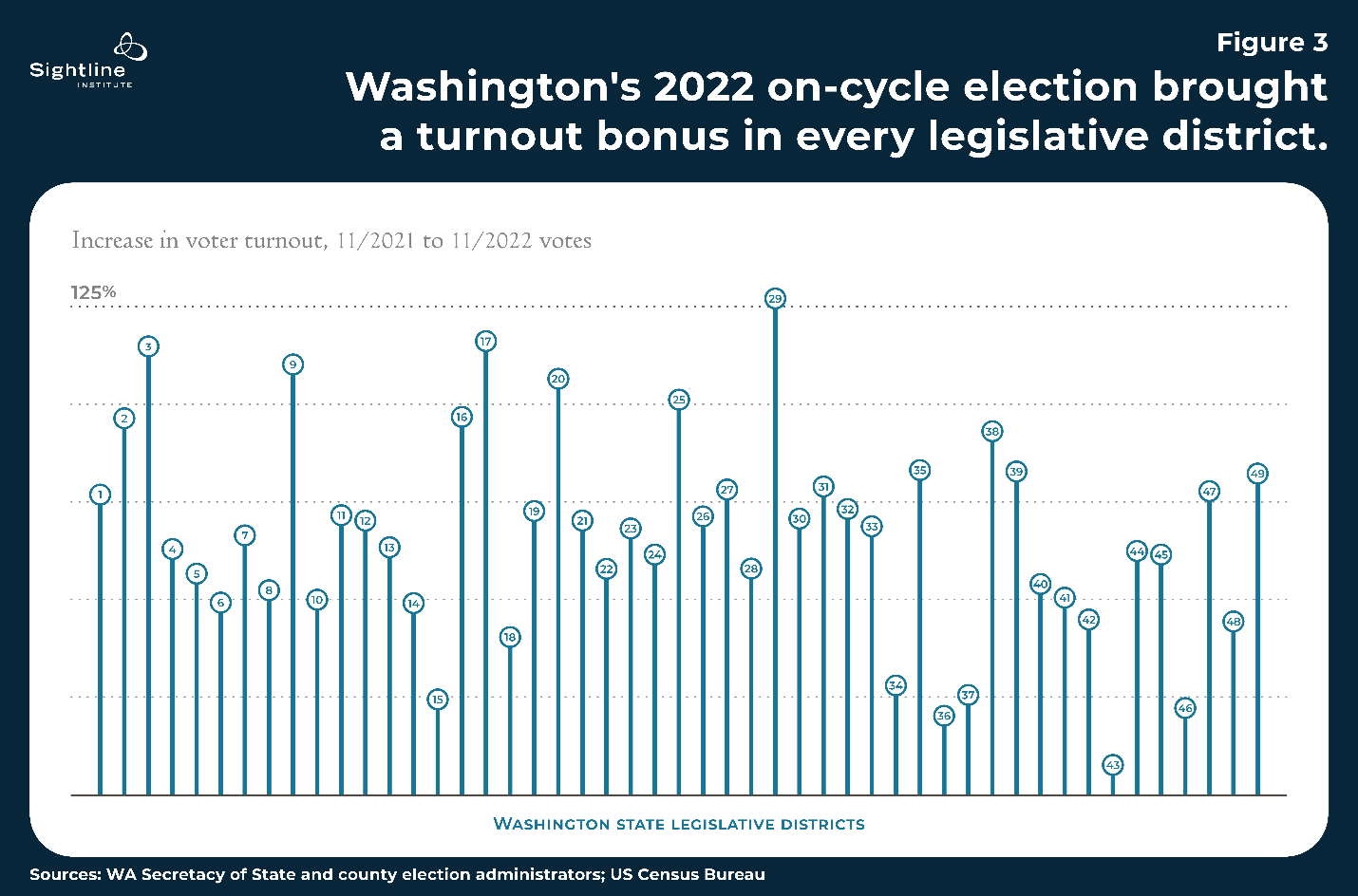

Permitting reform is the topic du jour in US climate circles. Renewable energy advocates and fossil fuel boosters alike are rallying to speed governmental approval of energy projects. At the same time, some progressives decry this effort as a misguided ruse to dismantle bedrock environmental and community protections.

How should climate leaders make sense of these debates? Just how big a barrier is permitting, really, to building the electric power grid Cascadia needs to decarbonize its economy? In short, how much should we worry about permitting?

At first glance, permitting transmission facilities in the Northwest looks like a hot mess. The only new regional line, the Boardman to Hemingway (B2H) project, crawled through federal and state approval processes for 14 years. Idaho Power and PacifiCorp, the line’s sponsors, still have not broken ground. B2H being the only new big wires project that is even close to construction in the Northwest may be further evidence that permitting is broken.

However, future transmission projects in the region could have it easier. Recent federal policy and regulatory efforts to shorten review processes and improve permitting coordination may lower some of the hurdles B2H faced. And Oregon’s state-level review, which B2H underwent, is among the most complex in the region; projects routed through other states might start moving dirt more quickly.

Still, the mounting climate crisis demands that Northwest policymakers do more than wait for the next transmission project to come up and hope for the best. They can bulk up staff capacity at regulatory agencies and tribes, which must review unprecedented volumes of new clean energy projects. They can immediately identify high-priority routes for new transmission lines and conduct preemptive environmental reviews and tribal consultations. They can enable—or better yet, require—tight alignment between state and federal review processes. None of these actions would mean jettisoning bedrock environmental protections or trampling on tribal and community rights.

With 2023 on track to become the hottest year on record, the Northwest needs to move fast to approve critical transmission projects, without surrendering its tools to block dirty or unjust energy proposals.

What is permitting, and how does it work in the Northwest?

Permitting is the process of federal, state, and/or local governmental agencies granting a developer the necessary approvals to build, upgrade, or operate a transmission line. The types of permits a transmission facility needs depend largely on where developers site the project and who owns the land it will traverse.

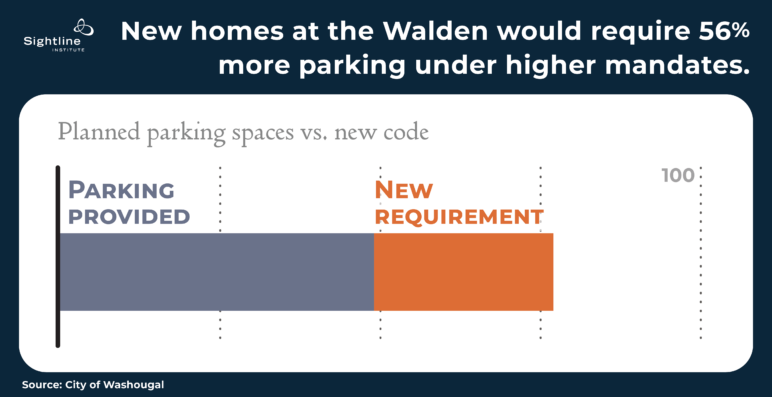

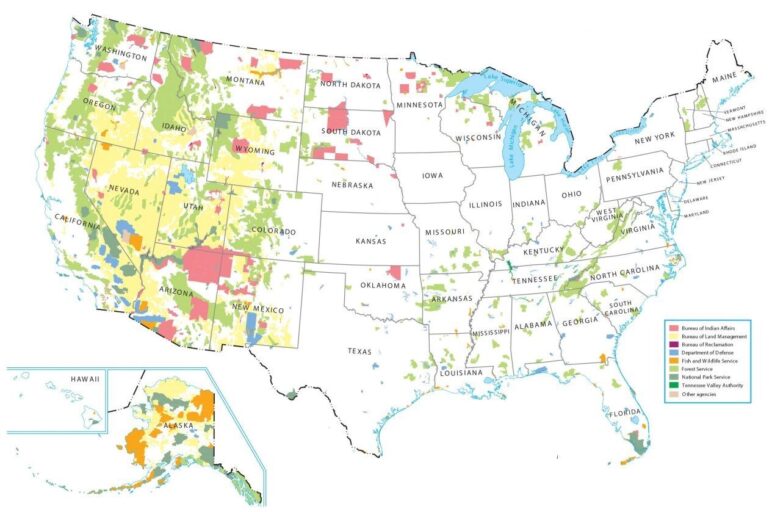

In the Northwest, as in the West writ large, the high percentage of land the federal government owns almost guarantees that interstate transmission lines require federal permits. One-third of the B2H route, for example, runs across federal land. The map below shows the federal land in the United States, with different colors identifying which federal agencies have jurisdiction; areas shaded pink and labeled as Bureau of Indian Affairs are tribal reservations.

If a project crosses federal land, it will trigger review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and likely several other laws, such as the Endangered Species Act, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act. The National Historic Preservation Act requires government-to-government consultation with federally recognized tribes the project could affect, whether because it crosses tribal land or because the land it traverses holds tribal religious or cultural significance.

Figure 1. Map of federal lands in the United States.

In addition, transmission line developers are likely to need state and/or local approval. In Montana, Oregon, and Washington, the state holds the ultimate authority for permitting most big transmission lines. Before state agencies can issue permits, both Montana and Washington compel environmental reviews modeled after NEPA, while Oregon requires a bespoke process for assessing projects against a set of environmental and other standards. Idaho has neither a state-level environmental review process for energy facilities nor a state-level permitting process. A transmission line running through the state needs permits from each county it touches.

Is permitting broken? Examining three common claims in the Northwest

Idaho Power gives at least three explanations for B2H’s snaillike approval process, and these arguments echo those that permitting reform advocates tend to make across the United States. Sightline analyzed each in turn, exploring their relevance given recent policy and regulatory developments and the broader Northwest context.

Claim 1: Environmental reviews are unnecessarily protracted

Permitting reform advocates tend to direct much of their ire at the purportedly excessively long environmental review processes that federal and/or state laws oblige governmental agencies to follow before issuing permits.

At first glance, B2H’s experience supports reformers’ arguments. It took seven years for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to complete a NEPA-mandated federal Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and another four years for Oregon’s Energy Facility Siting Council (EFSC) to complete its state-level review.

However, the same fate may not befall future transmission projects in the Northwest. For starters, the seven years it took BLM to complete B2H’s EIS is an outlier; multiple independent analyses have found that EISs take, on average, roughly three years to complete. Further, the 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act imposed a new, albeit controversial, two-year deadline on the NEPA process. And in August 2023, the US Department of Energy (DOE) proposed a new rule that would set two-year deadlines for federal environmental review and permitting of transmission facilities specifically. The DOE rule also aims to improve coordination between the multiple federal agencies that must grant a project approval. (B2H, for example, needed authorization from BLM, the US Forest Service [USFS], the Department of the Navy, and the Bureau of Reclamation.)

In addition, some states in the Northwest impose deadlines or timeline goals, which could lead to faster future state-level assessments than the one Oregon completed for B2H. Montana, for example, gives its Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) nine months to complete state environmental reviews of transmission lines.

“I don’t see the state being the roadblock,” Craig Jones, who leads environmental reviews and permitting at Montana’s DEQ, told Sightline.

Indeed, Oregon may have the lengthiest review process in the Northwest. Some renewable developers consider the state to impose “one of the—if not, the—most onerous permitting processes in the country,” Max Greene, deputy director at the energy advocacy organization Renewable Northwest, said at a recent public EFSC meeting. While Oregon sets a 12-month deadline for EFSC to issue a site certificate, in practice, timelines can extend far longer than a year. That’s in large part because of Oregon’s automatic appeal requirement, known as its contested case proceeding, which allows members of the public to raise concerns about a project. A contested case proceeding is not subject to any deadlines. In the case of B2H, the process stretched for nearly two years—roughly double the time it took for other recent non-transmission projects in the state. EFSC is currently undergoing a rulemaking proceeding to improve the efficiency and clarity of its contested case process.

Even so, multiple sources Sightline spoke to hypothesize that Idaho Power’s lack of familiarity with and experience in Oregon may be partly to blame for B2H’s lengthy state-level review. Plus, some decry the emphasis on time limits as ignoring the deeper issue of regulatory agency capacity constraints. Indeed, one of the only comprehensive reviews of NEPA timelines found that “staff availability, a lack of expertise, [and] inconsistent funding” are major drivers of NEPA delays. A senior representative at a major utility in the Northwest echoed the sentiment in a conversation with Sightline.

“We don’t want a bad project pushed through that doesn’t answer questions,” she said. “Then we’re faced with lawsuits.” Instead, she said, she’d rather see further investment in staff capacity at state permitting agencies.

Claim 2: Federal and state permitting processes are out of sync and duplicative

Federal- and state-level environmental reviews are also difficult to align, even when they effectively work toward the same goal, according to permitting reform advocates.

Again, this claim does appear to hold true in the case of B2H. Idaho Power first attempted to initiate its federal and Oregon environmental review processes in parallel. However, the company quickly found that doing so was virtually impossible, Mitch Colburn, Idaho Power’s vice president of planning, engineering, and construction, told Sightline. Thus, the utility paused the state-level review until the federal government had completed its analyses and approved the project.

The difficulty in syncing the two processes is largely because, unlike nearly 20 other states, Oregon did not model its environmental requirements after NEPA. NEPA obliges federal agencies to evaluate a “range of alternatives” to a given project before making a decision, whereas Oregon’s process requires application of a set of standards to single project.

“An applicant really must know what the final route approved by the lead federal agency will be to be able to conduct surveys and prepare materials necessary [for Oregon’s review],” an Oregon EFSC representative told Sightline. Oregon’s standards demand detailed analysis that often goes above and beyond what NEPA calls for, she explained. BLM analyzed more than 40 route variations for B2H; applying Oregon’s standards to all 40 of them would have been a gargantuan task.

A future transmission project running through Montana or Washington may be better able to sync up state and federal reviews. (Idaho has no state-level review.) Both states modeled their policies after NEPA and allow state agencies to adopt NEPA analyses to avoid duplication.

“We work together on one document to meet both of our needs since a lot of our [work] overlaps with [the federal government’s],” Jones of Montana’s DEQ explained.

Similarly, in Washington, “if there is going to be a [state environmental policy act (SEPA)] review and a NEPA review, you can adopt portions of each other’s analyses,” a representative from Washington’s siting and permitting agency told Sightline.

Claim 3: State and local interests hold too much sway over nationally important lines.

One of the most common calls for transmission permitting reform in the United States is to expand the federal government’s power and allow it to override state or local inaction on or opposition to new wires. Unlike for interstate natural gas pipelines, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) cannot authorize interstate transmission lines over state objections or grant project developers eminent domain power over state, local, or private land.

“I would have FERC be the one-stop shop [for permitting],” Adam Richins, Idaho Power’s chief operating officer, said on a 2023 podcast during which he shared “horror stories” from B2H’s permitting process.

In fact, the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act did marginally expand FERC’s permitting authority over transmission lines. The agency can now approve a line that the DOE deems to be in the national interest if states have denied a permit for the project. Previously, FERC could only use this authority in the case of state inaction, not outright denial.

But many argue for expanding FERC’s authority even further. Senator Joe Manchin’s (D-WV) controversial 2022 permitting bill would have allowed FERC to authorize interstate transmission lines that DOE deems are in the national interest without waiting for state denial or inaction. It also would have given transmission developers that received a permit from FERC eminent domain powers over state-owned land. Lawmakers cut these provisions, though included the rest of Manchin’s so-called dirty deal in the 2023 debt ceiling bill. Separately, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Representative Mike Quigley (D-IL) have twice introduced the Streamlining Interstate Transmission of Electricity (SITE) Act. This measure would grant FERC permitting authority over certain large interstate transmission projects even if they are not in DOE-designated National Interest Electronic Transmission Corridors.

Expanding FERC’s transmission permitting authority is a worthy national decarbonization strategy. But doing so would change nothing about the federal permitting process, which was the longest part of B2H’s approval timeline. Plus, expanding FERC’s authority could spark political backlash in Oregon and Washington, given it would essentially render these states’ bedrock environmental review processes obsolete for certain transmission lines. It might be a better strategy, then, to exempt certain high-priority transmission lines from state-review processes through state policy that Northwest leaders devise with tribes, environmentalists, and others.

State leaders can do more to alleviate permitting headaches

Still, Northwest leaders can take proactive steps—and indeed, Washington already has—to hasten permitting processes for future wires projects critical to the region’s decarbonization goals.

1. Fully staff state agencies and tribes

State permitting and siting agencies and tribes need enough staff to be able to properly and quickly evaluate the swell of new clean energy projects, not just transmission lines, coming their way. But Oregon and Washington’s relevant agencies each count just roughly ten full-time employees working directly on siting and permitting. And many tribes lack the staff to evaluate projects for cultural or environmental impacts, let alone evaluate them more quickly.

“When I first started [in 2005], we reviewed approximately 200 projects a month. We are up to, on average, 1,000 projects a month,” Steven Moses, the Snoqualmie Tribe’s director of cultural resources, explained as part of Washington’s 2022 Transmission Corridors Work Group. Moses was presumably referring to any projects requiring tribal review, not just clean energy ones. He works with a team of just three people who review projects.

Partly as a result of the state’s Transmission Corridors Work Group’s recommendation, Washington directed $2 million of its 2023–2025 operating budget to the state’s permitting and siting agency, the Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council (EFSEC) and more than $16 million to tribal capacity grants, including to support tribal “consultation on clean energy siting projects.” Oregon also recently granted its EFSC the authority to hire another siting analyst, according to Diane Brandt, Renewable Northwest’s markets and transmission director.

Still, states can do more. A Sightline source who works closely with several tribes in the region argued that resources for tribal capacity are still far from sufficient to meet the tidal wave of new projects. Similarly, a utility executive told Sightline, “From my perspective, you can’t have enough [Washington] EFSEC staff.”

All Northwest states would be smart to continue and deepen these capacity investments.

2. Map and assess priority transmission routes

Northwest leaders can also get a head start on future environmental reviews. They can convene tribes, renewable developers, utilities, the Bonneville Power Administration, local leaders, environmentalists, and others now to map all the potential transmission corridors in the region, assess their likely environmental and cultural impacts, and identify the highest-potential and lowest-conflict routes. As part of this effort, they could evaluate the suitability of siting transmission lines along highways or other already developed land. And they can leverage existing analysis by BLM to identify routes on BLM or USFS land in 11 western states that avoid “known resource and environmental conflicts.”

Here, too, Washington is beginning to lead the way. In 2023 the state directed EFSEC to conduct assessments, known as “nonproject” EISs, for electric transmission lines in geographic areas suitable for those types of facilities. The law compels EFSEC to request input from federally recognized tribes and overburdened communities and to use the nonproject EISs as a starting point for future project-specific ones. However, as of September 2023, EFSEC had not yet started this work; the council was still trying to hire someone with the necessary expertise.

Other states in the region can follow Washington’s example. In fact, in 2023 Oregon considered but did not pass a bill that would have required state agencies to identify ideal locations to site transmission lines. Lawmakers would be smart to revive that effort.

And if advanced assessments end up failing to shorten the timelines for project-specific state reviews, leaders in the region could consider going a step further: they could waive some or all components of state-level project-specific reviews for proposals sited within designated priority corridors. (For a somewhat analogous example, in 2023 Washington exempted from its State Environmental Policy Act [SEPA] housing developments that comply with local comprehensive plans.) However, the state would need to solicit genuine tribal agreement on any effort to waive state-level reviews. Efforts to reform Washington’s SEPA several years ago “went horrible from a tribal perspective,” according to Moses of the Snoqualmie Tribe, who said tribes were “called in late” and “bullied by various groups.”

3. Enable and formalize federal-state coordination

Finally, Northwest leaders, especially in Oregon and Washington, can do more to sync federal and state environmental reviews and avoid unnecessary duplication. Idaho Power, the permitting lead for B2H, and Oregon’s EFSC actually agree that that state’s process is fundamentally misaligned with the federal review process—a fact that suggests that action from Oregon policymakers is in order.

The federal EIS for B2H, which stretches thousands of pages, assessed the project’s impacts on dozens of issues, including cultural resources, soil, minerals, paleontological resources, sensitive plant species, wetlands, wildlife habitat, endangered and protected species, agriculture, recreation, and wilderness lands. Oregon’s own review, which came in at more than 700 pages, assessed the project on several similar, if not identical, topics. At a minimum, surely Oregon can devise a way to conduct at least some of its assessments in conjunction with federal partners.

In Washington, coordination between SEPA and NEPA may be easier. Still, no recent transmission project has practically tested it. As such, policymakers could proactively bolster and formalize collaboration between state and federal permitting agencies. Washington’s EFSEC could develop standard Memorandums of Understanding or cooperative agreements with federal agencies likely to be involved in transmission line permitting. Indeed, the agency could do that now with the federal agencies that will, along with Oregon, need to assess the Cascade Renewable Transmission project, the first new line to be proposed in years that would span Washington.

Still, Oregon and Washington lawmakers may find that syncing federal- and state-level environmental reviews continues to elude transmission projects. In that case, they could again consider taking the further step of exempting certain new wires facilities—namely those already undergoing federal reviews and in agreed-upon corridors—from the additional layer of state-level review.

Permitting reform that preserves PNW values

Permitting reform has captured the attention of the United States’ climate and energy circles, including those in the Northwest. With B2H as the only regional transmission project in the Northwest moving forward, it’s hard to say definitively yet if its drawn-out permitting experience is the exception or the rule.

Leaders shouldn’t wait to find out. They can expand state regulatory and tribal capacity to review new projects; identify and assess high-priority, low-conflict corridors for transmission lines; and formalize federal and state coordination of environmental reviews. Taking these actions does not mean jettisoning the region’s commitment to environmental protection or repeating the historic injustices of the last century’s energy build-out against tribal nations, when utilities and public agencies dammed salmon runs and homelands with little regard for the rights of Indigenous groups.

The region can’t afford another 14 years to permit the next big transmission line. Proactive steps now, alongside a plan and way to pay for new lines, can help us get to yes at the clip the climate demands.