In 2016 and 2017 I wrote a pair of articles for Sightline titled “How Seattle Killed Micro-housing” and “How Seattle Killed Micro-housing Again“ that told the story of Seattle’s micro-housing boom and subsequent backlash. I laid out how a variety of policymakers, city boards, and citizen groups worked in concert to shut down a steady, abundant supply of small, low-cost housing, and replace it with something significantly larger, less plentiful, and more expensive.

The story touched a nerve (the articles were popular and shared widely) and provided a concrete example of the kind of regulatory malpractice that makes it so difficult for communities to create the full range of home types and price points that our city neighborhoods so desperately need.

The years since those articles were published have not brought any good news. Despite several opportunities, Seattle has shown no serious interest in revisiting its micro-housing policy. To the contrary, the city has taken further steps to make the situation even worse.

In years past it was easy to deflect criticism about micro-housing policy because the changes were so new that local lawmakers could always hide behind a lack of data as a justification for inaction. Now that the rules have been in place for several years, we have a much clearer picture of what’s going on.

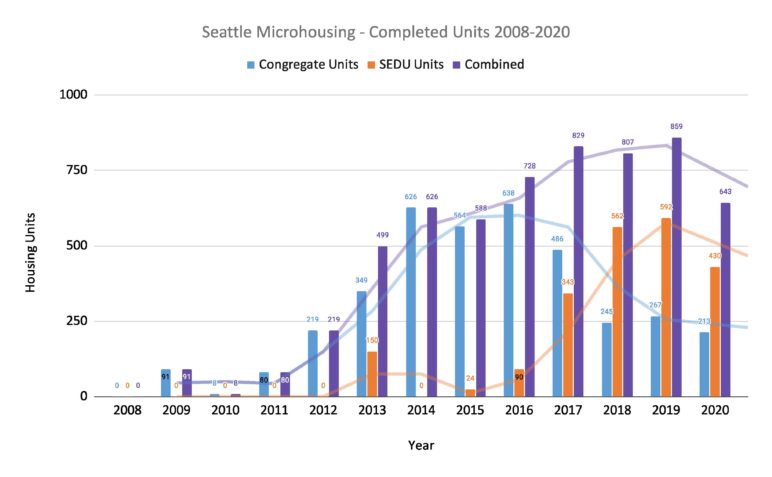

The upshot: As predicted, Seattle really did all but abolish the “congregate” form of micro-housing. Builders switched to the “small efficiency dwelling unit” (SEDU) form, producing larger, more expensive units, but in recent years SEDU construction has also begun to decline. This loss of relatively low-cost homes during a housing crisis is a direct result of decisions made in the past by Seattle policymakers, and today’s elected leaders could just as easily decide to undo those past mistakes.

The Data

This summer my daughter and I sat down with four different data sets. The first was a micro-housing tracking list collected by the Seattle Department of Planning and Development back in 2014. The second was a private database of congregate and SEDU projects collected by Kidder Matthews, publisher of an annual report on micro-housing. The third was the building permit data from data.seattle.gov, and the fourth was the land use permit data downloaded from SeattleinProgress.com. We made a project of combining these data sets, removing duplicates, resolving conflicting entries, and auditing to produce our best attempt at a complete data set of all congregate housing and SEDU development from 2008-2020.

In previous articles on micro-housing production, I considered the immediate effects of recent legislation. Back then, we analyzed the quantity of building permit applications, since changes to this metric register fairly quickly. Now, with the luxury of a longer timescale, we tracked two more meaningful data sets: projects with an issued building permit and projects that have finished construction. Both show production numbers that are a little lower compared with our previously published numbers, as each successive step in the development process weeds out some of the projects in the pipeline, which can get delayed or mothballed for any number of reasons.

Here’s what we found:

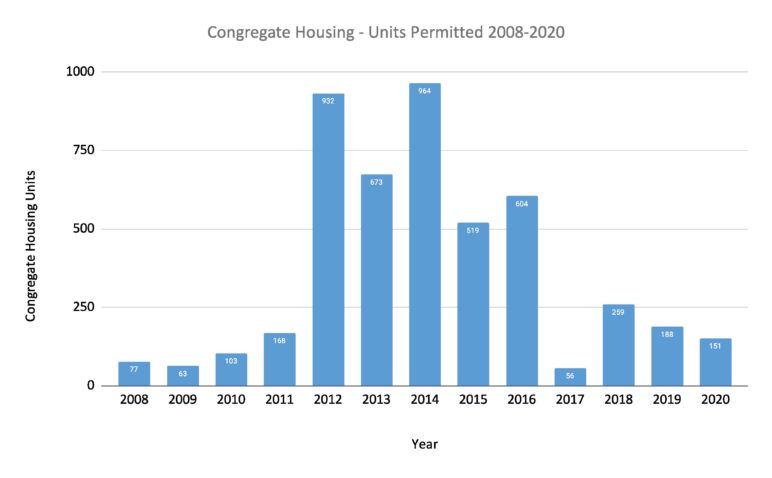

1) Congregate housing production has dropped significantly

Building permit volume is down about 85 percent from its peak, and unit completions are off by about 70 percent. This might seem like slightly better news than the 90 percent loss that we saw back in 2016 when we were looking at permit applications, but really what we are seeing is that once projects enter the system, some of them take longer than others to finish. Though most projects move through from the application stage to a finished project in three or four years, there are a significant number of stragglers that take years longer to progress. Those legacy projects spread out over time, and so they flatten the trends a little bit.

There are only a handful of developers left in the congregate housing market. Anew Apartments has one project starting construction, but has no further projects planned. My firm, Neiman Taber, has two projects (in partnership w/ Hamilton Urban) finishing construction this year, but we also have no further projects in the pipeline. Apodment.com has a handful of projects in various stages. The Apodment company is the last developer remaining with any projects at all in the permitting pipeline. No developer submitted a permit for a new congregate project in 2020. Repeat: zero congregate projects in 2020.

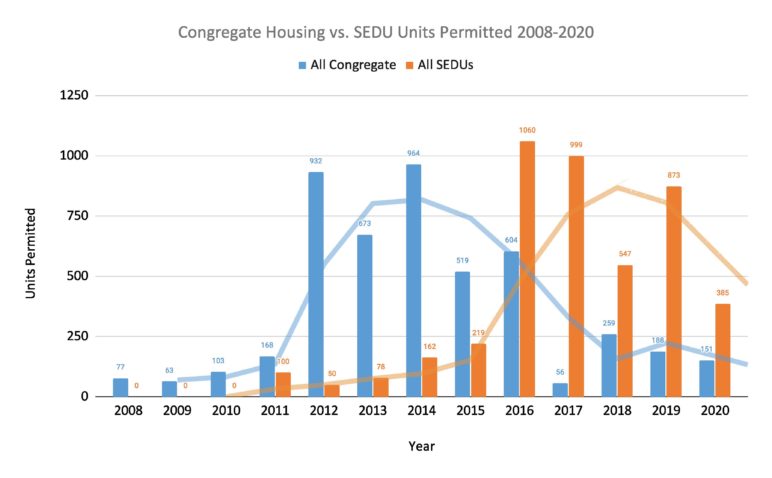

2) SEDU production has taken the place of congregate housing production

This shift stands out quite clearly in the data. It played out exactly as early trends pointed to back in 2015: Micro-housing developers shifted immediately away from congregate housing and into SEDU production. The two trend lines echo each other almost perfectly.

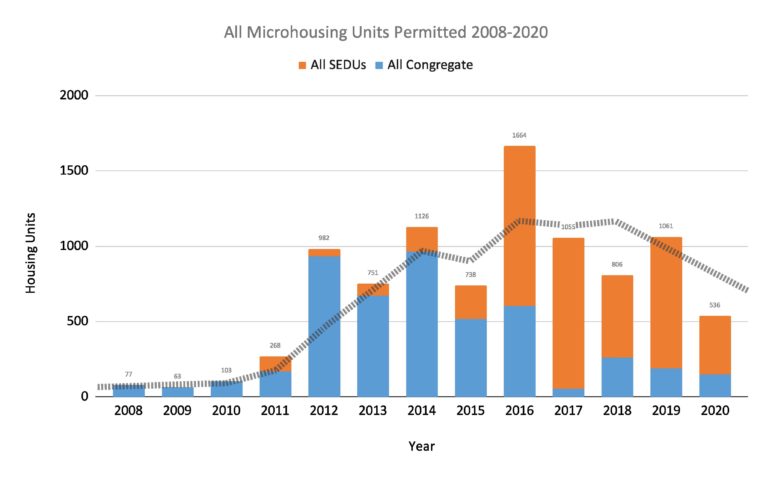

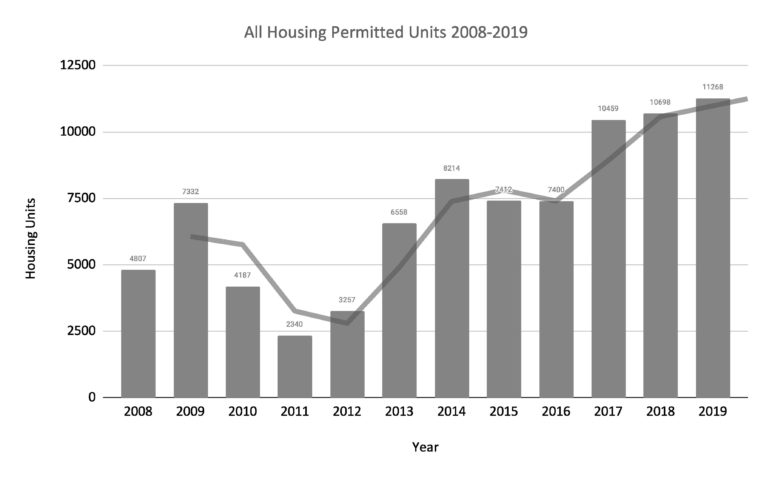

3) Total micro-housing production is falling

Initially, the falloff in congregate housing was backfilled by SEDU production, but since 2018 SEDU permits have been in decline. Application of a moving average trend-line reveals a clear downward trajectory. Completions trail behind permitting by about two years but in the completed projects graph (at the top of the article) you can see the same shaped trend line forming. In case you’re wondering, the micro-housing falloff doesn’t correlate with housing permits in general, which have climbed steadily since 2011, with overall volumes rising even as micro-housing permits have tailed off.

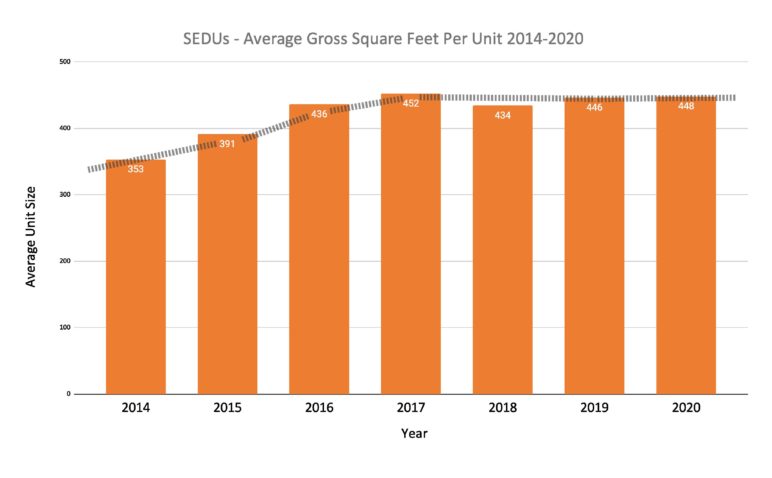

4) SEDU projects have become less efficient

In 2014 the average SEDU project needed about 350 gross square feet of building area for every housing unit. Over the next several years, Seattle introduced a series of new policies that required the units to be larger, increased the space required for back of house requirements like bicycle parking and waste disposal, and up-zoned more of our land into mid-rise zones where the buildings have elevators and all of the units are required to be accessible. By 2020, the gross sf per unit for SEDUs was up a whopping 28 percent, to almost 450 gross square feet per unit.

So that’s what’s happened. Of course the “what” part of the story is only one piece of the puzzle. There are a few interesting “why” questions that these figures raise:

Why has congregate housing production dropped?

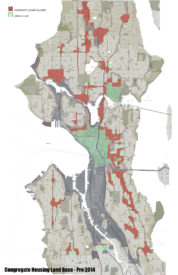

This question is the least mysterious. Seattle’s 2014 anti-micro-housing legislation was designed to generate this outcome. The following three maps show the changes to the land base where congregate housing is both allowed and is economically viable. For the purposes of this analysis we have disallowed any zones where congregate housing is technically permitted but the allowed building heights are taller than five stories. Projects taller than five stories are almost certain to have an elevator; projects with elevators must have 100 percent of their units be accessible; and the additional area required for accessible maneuvering clearances forces the unit size up and the unit count down to the point where the economic model for congregate micro-housing just doesn’t work.

Prior to the 2014 anti-micro-housing legislation, congregate housing could be built practically anywhere in the city where low-rise development was allowed (shown in red). (Click on the maps to see a larger version.)

After the 2014 changes, the land base where congregate housing worked was reduced to just a few remnants, mostly along automobile corridors like Aurora, Rainier Avenue South, and 15th Ave Northwest. The land area remaining for congregate housing development is so small you may need to enlarge the image to see it.

After the 2014 changes, the land base where congregate housing worked was reduced to just a few remnants, mostly along automobile corridors like Aurora, Rainier Avenue South, and 15th Ave Northwest. The land area remaining for congregate housing development is so small you may need to enlarge the image to see it.

In 2019 when Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) came into effect, most of the remaining areas were either up-zoned to a height (75 feet) where congregate housing isn’t viable, or re-zoned to a category like NC2 where congregate housing is not a permitted use.

In 2019 when Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) came into effect, most of the remaining areas were either up-zoned to a height (75 feet) where congregate housing isn’t viable, or re-zoned to a category like NC2 where congregate housing is not a permitted use.

The need to undo the restrictions described above was originally raised by Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda Report in 2015 (see page 24). It was reiterated again by the Affordable Middle-Income Housing Advisory Council in 2019 (see page 42). Despite the official attention congregate housing has received from our various blue ribbon housing commissions, the city has taken no action on these recommendations, nor is there any legislation in the works.

The need to undo the restrictions described above was originally raised by Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda Report in 2015 (see page 24). It was reiterated again by the Affordable Middle-Income Housing Advisory Council in 2019 (see page 42). Despite the official attention congregate housing has received from our various blue ribbon housing commissions, the city has taken no action on these recommendations, nor is there any legislation in the works.

Why did SEDUs replace congregate micro-housing?

This one’s also quite simple. It’s the corollary to what happened to congregate housing. SEDUs are allowed in any zone where apartment development is allowed. SEDU units are large enough that they can be designed to meet accessibility standards and still be within a size range that is economically viable, so they can be developed under Seattle’s newer, taller zoning. In a nutshell, congregate housing has been starved of a land base where it can thrive, while SEDUs have not.

Why is SEDU production now falling?

This one is a bit of a sleeper issue. I was not expecting to find it in the data, and the trend isn’t as obvious as what happened with congregate housing, but it does track with the currents that we have observed in our practice, namely that SEDU projects have become a decreasing percentage of our workload, and that a fair amount of the SEDU projects that we permitted recently aren’t getting built. I don’t think there is any single reason that this is happening. Rather, I suspect it is the confluence of several problems:

- Construction costs, land prices, and regulatory burdens are at all time highs. This is putting the squeeze on projects of all types. One common response developers have to this pressure is to try to outrun the problem by putting together bigger projects that can spread fixed costs over more units and find an economy of scale that can reduce construction costs. Micro-housing developers tend to be small fish, and larger institutional scale developers lean toward more traditional project types, so it’s not surprising this compression in the market might put the squeeze on micro-housing development.

- One tool that some developers employ to try to make their projects work is the Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE), where developers provide lower rents to income-qualified residents in exchange for a property tax exemption. In areas of the city where market rents are lower, participation in the MFTE program can sometimes make or break the viability of a project. In 2016 Seattle enacted new MFTE rules that lumped SEDUs into a price category that ensures the MFTE participation is a money loser for SEDU projects. Accordingly, MFTE participation has evaporated as a tool for making SEDU projects pencil out in marginal rental markets. Many of our clients who were previously interested in SEDU projects have shifted their focus to building small one-bedroom apartments, where the MFTE program allows for a rental rate discount that is reasonably proportional to the value of the tax break, benefiting the project bottom-line.

- Over the past several years the city has enacted a series of small administrative and legislative tweaks that have made SEDU apartments larger and the overall buildings less efficient. The net effect of these changes is that the average SEDU project in 2020 is roughly 28 percent less dense than it was in 2014 before all of the rule-making began in earnest. To fully unpack all of these changes is a bit of a chore, but the biggest changes include:

- The 70-7 rule explained in “How Seattle Killed Micro-housing”

- Directors Rule 7-2016 explained in “How Seattle Killed Micro-housing again“.

- Directors Rule 9-2017, which between its text and its application has created new requirements for larger in-unit storage areas and less design flexibility for their configuration.

- Expansive new bicycle parking legislation resulting in a ~3 percent reduction in the unit count of a typical SEDU project.

- New SPU administrative requirements that roughly double the size of most waste rooms. New legislation that will expand these mandates further has been introduced but is on hold pending the outcome of a State Environmental Policy Act appeal.

The issues I have outlined affect the viability of all types of projects, but they fall most heavily on micro-housing development. These projects are generally smaller and thus lack the access to institutional capital and economies of scale that can float larger projects. In a similar fashion, bureaucratic burdens like the bike parking and the waste rooms fall more heavily on smaller projects and smaller units, as the mandates are levied on a per-unit basis. The MFTE issue is just straight-up bad administration. The city government put its thumb on the scale, won’t take it off, and frankly will barely even acknowledge the issue.

What’s next for Seattle micro-housing?

We now have years of data that confirm the predictions we made back in 2014 and the early trends we reported on in 2016 and 2017. Things have continued to play out exactly as we expected:

- Seattle has pretty much killed off congregate housing as a meaningful source of more affordable market-rate homes.

- Seattle replaced congregate housing with SEDUs, regulated SEDU projects to produce larger, more expensive units, then drove the resulting housing to be less affordable by cutting off access to the MFTE program.

- All forms of micro-housing are in decline, driven by regulatory policies that make the housing more expensive for developers and renters alike.

- Seattle has tasked two blue ribbon commissions with fixing housing policy. Both have made similar critiques of the city’ micro-housing policies and have recommended action.

- Neither the Mayor’s office nor the city council have taken any action on the recommendations to ease restrictions on micro-housing.

In 2014 Seattle embarked on a campaign to “fix” micro-housing. In doing so, we have done quite the opposite, and have cemented in place a long term trend where market rate development is increasingly unable to provide low-cost housing options to a city that desperately needs them.

The hard part about turning this situation around is that these anti-micro-housing policies aren’t accidental. The city took these actions because powerful constituencies perceive micro-housing as a threat to their interests and values. If you already live in Seattle and you’re already comfortable, allowing more homes means you might lose some of your quiet enjoyment and convenient street parking. If you’re a social justice advocate, supporting micro-housing might feel like acceding to the status quo—figuring out ways to help poor people with the tools we have, instead of growing the safety net. If you’re a housing non-profit, micro-housing violates a guiding principle that affordable housing should conform to middle class norms, and micro-housing doesn’t. And if you’re a politician, rolling up your sleeves and fixing this mess means ignoring the misgivings of all of these powerful constituencies and throwing your lot in with developers.

There is a tremendous case to be made for micro-housing. It allows people to live in places that they’d otherwise be priced out of. It helps people find community. It uses far less energy per person than conventional housing and enables low-carbon, transit oriented, pedestrian lifestyles. And most plainly, because in the midst of a housing crisis, denying housing options lower income people can afford is plainly, indefensibly, wrong. The gravity of this argument will win out in the end. Let’s hope 2021 is the year our political leaders wake up on this issue and get to work.

David Neiman is a principal at Neiman Taber Architects, where he is deeply involved in micro-housing as an architect, developer, and proponent in the public policy sphere. He served on the HALA committee. His firm works to create plentiful, high-quality, small unit housing, designed to support livability and promote community among residents. He has contributed several articles on Seattle micro-housing and coauthored a Sightline article on missing middle housing and design review for Sightline in February 2016.

peg staeheli

Honestly – I would be more in favor of micro housing if a few simple things were included in siting:

1) ability to have load/unload zone directly in front of complex.

2) If alley access- then a drop off zone in back

3) waste is real – don’t know the answer but agree sf/unit does not match scale

4) Urban trees- If these have no room for trees at the minimum they should pay into a tree fund. ( trees planted on the current micro sites have no viable room)

DAVID NEIMAN

It’s natural to be ambivalent about micro-housing. It’s a compromise between what we’d like people to have and what they can afford. Most people would choose more space for themselves (and on behalf of others) if they could. But they can’t. Conventional market rate housing can’t deliver homes at a low enough price, and by an order of magnitude there isn’t enough funding out there to build social housing. So the choice for many people is either to build micro-housing or consign a large swath of the urban working class to long commutes, decrepit housing, doubling and tripling up, or a combination of all three.

All multi-family projects need load/unload areas. Not just micro-housing. Typically this is provided as a loading zone along the front of the building. The city of Seattle is quite accommodating in this regard. We have never had a problem getting a load zone for any of our projects.

Every building needs a place for waste pickup. In recent years Seattle has massively increased the footprint they require for this function. For a large apartment complex, the costs of these features are not a big deal, but for small micro-housing projects they are existential problems. Policies like these that prescriptively impose “best practices” solutions for all projects reduce unit yields and increase costs to the point where the projects can’t deliver the units plentifully or inexpensively. When this happens, the economic model breaks, and the projects don’t get built.

Trees are not a unique issue for micro-housing. They are an issue for all dense urban development. It’s an unusual project that can’t accommodate planting some trees. That’s rarely the issue. The issue is whether we allow removal/re-planting/mitigation, or if we prioritize the preservation of individual existing trees at the cost of providing homes.

Seattle has a housing affordability and homelessness crisis. I don’t think it’s reasonable to say that we have a waste pickup crisis, or a bike parking crisis, or a tree canopy crisis. And yet, our legislative priorities don’t seem to reflect this.

Steve Dotterrer

Very interesting collection of information on micro-housing production in Seattle. As a Portland resident, it is probably dangerous for me to comment at all. Nonetheless, I feel the need to do so because the conclusion reached– essentially that regulation (what you call bureaucracy) controls the market for housing is patently inaccurate. Firstly, the market framework for housing (as set by federal policies, individual housing desires and the organization of private capital) in the US as a whole has a significant impact on housing in Seattle. Continued low interest rates, rising minimum wages in many metro areas, the way REITs organize themselves, the mortgage interest tax deduction all have a significant impact on the Seattle housing market. In Seattle, the rapid growth of high-wage employers like Amazon over the time period considered is a likely influence on your local housing market. Pretending that those influences can be ignored makes your conclusions suspect.

Secondly, your view that things like bicycle parking, ADA accessibility, and waste room requirements are merely bureaucratic impediments makes your analysis untrustworthy. Each represents an effort to attain “public goods” which Sightline promotes–reduced fossil fuel use and healthier humans, increased equity and increased recycling. Treating them as unworthy of inclusion makes this analysis that of a special interest and not helpful in aiming for an improved future.

In my view, more attention needs to be paid to the national and international setting and markets. Our metro areas, states and Cascadia itself can not ignore the national and international policies and markets we are part of. The solutions do not lie within the boundaries of Vancouver, Seattle or Portland.

I also think more solutions should be advanced. Blaming Seattle is simply shaming, not problem-solving. While that has become increasingly the public discourse at the national level, we should be doing better if we are really going to solve problems.

Maybe we should be adopting the Dutch waste and recycling approach in multi-family areas- you take your waste to publicly provided places rather than within your building. Maybe only 50% of high-rise units should be fully accessible. But getting to those approaches will require discussion about residents’ willingness to change current behaviors, and various groups coming to agreement on how to solve the problem. An assumption that “my answer is the right answer” is not a solution. It should be an opening concern and Sightline should frame it that way.

DAVID NEIMAN

Housing development, like all economic activity, is influenced by countless factors. So, it is beyond difficult to precisely assign cause and effect to specific actions as distinct from the background noise. However, what years of data is telling us is that the downward trends for micro-housing development are both real and counter to those for conventional housing development. I’d point you to the charts showing congregate vs. SEDU production that show the dramatic and immediate effect of the 2014 legislation and the gray chart that shows rising production for all forms of housing at the same time that micro-housing production is flagging.

Public policy is an endless tug of war between competing interests, with every decision redounding to the benefit of some interests and at the expenses of others. The challenge of governance is in choosing among these interests. In recent years, Seattle has decided that it is important to have massive bike rooms and capacious waste rooms. They are not wrong in that those are desirable features (for some). Every prescriptive mandate has a stakeholder for whom the requirement represents their interests. The error is in the unwillingness to acknowledge that these mandates come at a huge and disproportionate cost, not just to the developer, but to the housing economy as a whole.

Codes are meant to describe the floor below which no one can sink. Increasingly, our codes have been used to make everyone reach for the ceiling, to prescribe “best practices” in any number of ways. When we conflate the floor with the ceiling, we make it impossible for anyone to produce housing that is simple, basic, and inexpensive.

Ian Crozier

I was surprised to see the recent MHA upzones listed along with the regulatory burdens that have killed micro-units. Do you have a remedy in mind here?

DAVID NEIMAN

Congregate housing works best when the building are simple walk-ups, 3-4 stories tall. The land base where Seattle allows them is now mostly zoned for 7-8 story development. If congregate housing was allowed in our low-rise zones that would go a long way towards fixing the problem.

Over the last decade Seattle has twice bumped up the scale of our low-rise zones to create more mid-rise apartment zones, but has not done as much to grow the base where low-rise development can occur.

Essentially, congregate housing is another “missing middle” housing type – too intensive for single family zones but not a good fit for the mid-rise zones where we have been directing most of our new development.