Update, July 2023: In 2022, Oregon’s Land Conservation and Development Commission adopted rules to reduce minimum parking ratios for jurisdictions within metropolitan areas, with an option for cities to eliminate all parking mandates. It is a major step forward that will make it possible for future development to be constructed without building more heat islands.

Urban heat islands got national attention this past summer after a record heat wave in the Pacific Northwest killed hundreds. In Portland, where the heat disparities between neighborhoods are among the worst in the country, one thing jumps out when you look at maps of these places: huge parking lots.

Big parking lots create dangerous heat islands

When agencies publish guidance for how to break up heat islands, they usually suggest shady trees and lighter-colored roads. But one assumption goes relatively unquestioned: why do we have these huge parking lots in the first place?

“People don’t want to go there because they’re afraid of the blowback or something,” said Ted Labbe, a Portland-based habitat advocate who helped found the group Depave. In his experience, public officials will often talk about adding trees and rain gardens, but they never start by asking how much parking is really needed. “Pavement removal is the simplest, lowest-cost, lowest-maintenance intervention you can do,” said Labbe, but “surprisingly, pavement removal is not considered a best practice.”

How one zoning decision transformed a neighborhood

Large parking lots are not natural or inevitable. They do not spontaneously appear, like dandelions on the edges of roads. They are the outcome of a series of choices by property owners and the governments that regulate these owners. And those choices have consequences.

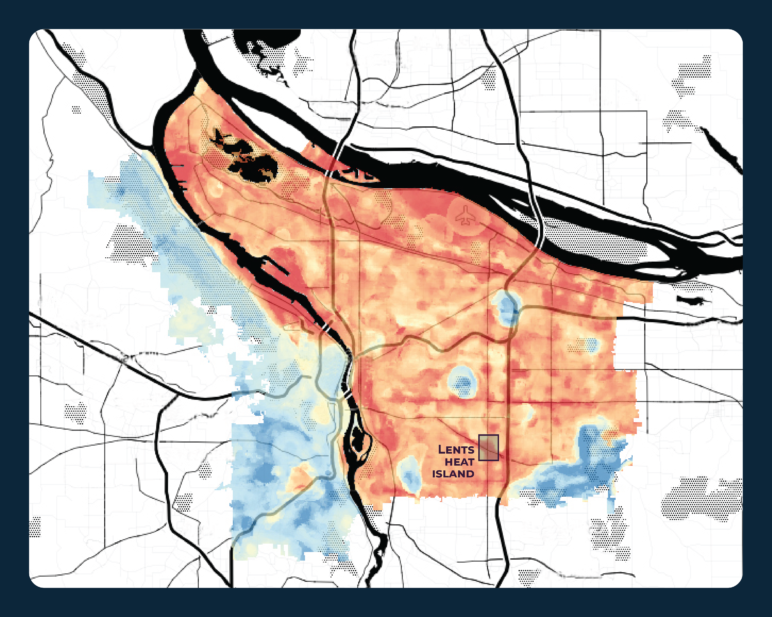

Sightline took a deep dive into one of the hottest areas of Portland: Southeast 82nd Avenue and Foster Road, the western anchor of the Lents neighborhood, marked off by the black rectangle in the map below. This area was largely redeveloped after Portland added its first parking requirements in its 1959 zoning code. The new code defined minimum off-street parking ratios for more than 50 types of businesses, from bowling alleys (two parking spaces per lane) to wedding chapels (one parking space per 56 square feet of public floor area).

The black rectangle in the southeast region of Portland shows Sightline’s study area, overlaid on Sustaining Urban Places Research Lab evening-timed urban heat island map.

Parking requirements are based on little or no data. Yet Portland joined in the mid-twentieth century car-centric planning craze that was sweeping the nation. According to urban planning scholar Donald Shoup in The High Cost of Free Parking, a survey of 76 cities in 1946 found that only 17 percent of them had parking requirements in their zoning code. Five years later, 71 percent had adopted them or were in the process of doing so. “Other than zoning itself, few if any other planning practices have spread more rapidly,” wrote Shoup.

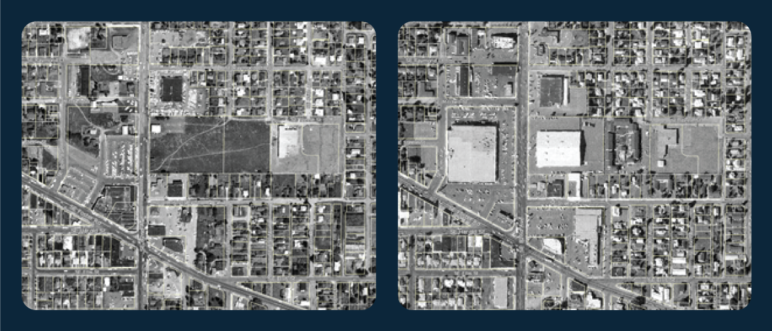

The development that came to Lents from 1960 (left below) to 1975 (right below), the years following Portland’s parking mandate, included the ample parking that city law had required.

Portland Maps aerial views of the Sightline study area: 1960 (left), 1975 (right).

Off-street parking in Lents did exist before the minimum requirements went into effect, but the new rules cast those norms in stone. Once new buildings were required to supply enough on-site parking for anyone who showed up in a car, the price that car owners would ever be willing to pay for parking in the area fell to zero. It also became pointless for a new building even to share its parking lot with a neighbor; after all, it was already required to create its own dedicated lot.

Even then, big parking lots weren’t the only way to do business. Businesses on the triangular block between SE Foster and SE Harold (outlined in yellow below) still operate in buildings constructed between 1911 and 1950. Today, multiple businesses share the parking lot, which equates to 1 parking space per 1,000 square feet of building area.

But since 1959, parking mandates for new construction kicked off a cycle in which people expected more and more parking. The red-outlined area in the map below, which was redeveloped after parking minimums went into effect, has 3 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet. By 1970, new big box stores were providing 4–5 spaces per 1,000 square feet, above and beyond what was required.

Google Earth aerial view, altered and labeled by Sightline Institute, available under our Free Use Policy.

Even way back in a 1954 Planning Advisory Service report on shopping center design, Architect G. Morton Wolfe wrote about the pressure to expand parking lots. “Many years ago it was considered good practice to provide as much parking area as the total area of the building. This was increased to two times the area and is on the upward swing now from 3 square feet parking area to each square foot of building.” After designing over a dozen shopping centers, Wolfe had given up on any logical formula and resorted to guessing.

The health impact of all that asphalt

Ever-expanding parking lots have serious side effects during heat waves, which are growing more frequent even in the temperate Pacific Northwest thanks to climate change. Parking lots absorb the sun’s energy during the day and release it back at night. “What’s making the news is the highs,” Lara Cushing, an environmental health scientist at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, told the New York Times. “But nighttime minimums have an impact on mortality.” Nighttime lows above 80 degrees are especially dangerous to the human body. Instead of giving our bodies getting time to recover, heat stress compounds in our systems. For people without air conditioning, opening windows overnight stops being an effective way to cool down a home.

During Cascadia’s June 2021 heat dome event, Professor Vivek Shandas, who researches climate resilience and urban heat at Portland State University, recorded an ambient temperature of 124 degrees Fahrenheit just ten blocks east from our study area. The pavement was a sizzling 180 degrees Fahrenheit, the highest recording he had taken in his life. “The big-box store parking lot—those are what really amplified these temperatures,” Shandas said at a recent presentation to Portland-based Families for Climate.

In his research, Shandas noted a tipping point where air temperatures start amplifying based on the size of the asphalt surface below: somewhere around 20,000 square feet of asphalt. A small residential street doesn’t have that signature bump in temperature, but an intersection like 82nd Avenue and Powell Boulevard does.

Shade from trees can help keep temperatures down, but unfortunately putting trees in the middle of parking lots is a partial solution at best. Shandas likened the environment to a 150 degree oven. Heat absorbed by asphalt not only radiates up into the air, but also down into the soil, which is compacted by the paving process—a challenging environment for a fledgling forest to lay down roots. That may help explain why requiring parking lots to include trees hasn’t always delivered the shade intended. And according to Shandas, heat signatures jump when as little as 20 percent of a parking lot is in direct sunlight. It’s far more common for a parking lot to have the opposite ratio, with only 20 percent shaded.

The consequences for Lents

This summer, more people died from the heat wave in Lents than in any other zip code in Multnomah County, an environmental justice red flag in the Rose City. Higher temperatures compounded the risks already faced by people living in the neighborhood, half of whose residents identify as people of color. Bisected by the I-205 highway and surrounded by high-traffic roads, the neighborhood has diesel pollution rates 10 to 20 times higher than state health benchmarks and asthma rates twice as high as the rest of the city (asthma, like other chronic medical conditions, makes people more vulnerable when temperatures spike). Residents also have fewer resources to draw on in an emergency, with median income 24 percent lower than Portland’s average.

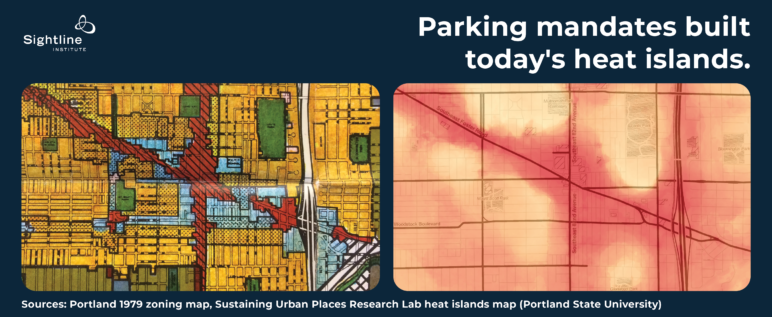

A 1979 zoning map (below) shows the correlation in Lents between commercial zoning, in red, which required off-street parking, and today’s heat islands. But these parking mandates that created such asphalt-rich areas like those in Lents were not applied evenly across the city. More central commercial zones in and near Portland’s downtown were exempt from building off-street parking, furthering disparities in the built environment between downtown and outer neighborhoods as Portland added more people and jobs in the decades that followed.

Parking mandates built today’s heat islands.

A post-parking mandate world: Smaller lots, fewer heat islands

Even though Portland has been chipping away at its parking requirements, virtually every city in Cascadia continues to repeat the Lents template by mandating parking lots in various locations, whether or not they’re needed. Nearly every jurisdiction, from small towns to big cities, makes it illegal for neighborhoods to gradually evolve beyond the need for so much parking. Unless some well-connected developer makes a self-interested argument for an exception, local officials have little incentive to ever reconsider the rules.

The result is more and more parking lots. A new shopping center in Springfield, Oregon, would require 3.3 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet of building. Oregon City, Wilsonville, and Troutdale require even more: 4.1 spaces per 1,000 square feet for retail, the cap set by regional government Metro in the 1990s and more than double what Portland’s code mandates. If the parking minimums Metro currently allows had been applied in 1959, the already sprawling red-outlined parking lots at SE 82nd and Foster in the graphic above would have been 40 percent larger.

A lot of these mandated spots are wasted. Study after study finds that available parking spaces far outstrip demand. After Buffalo, New York, repealed its parking minimums, nearly half of projects included less, resulting in 20 percent smaller lots than the previous code had required. Projects that would have had to build the largest lots shrank them the most. Compared to the six months leading up to the code change, when new construction provided 20 percent more parking spaces than the minimum, that’s a whole lot less asphalt.

Removing parking minimums doesn’t suddenly mean no parking, though—not in a world where most people still use cars to reach their daily destinations. “If a city removes its parking requirements, land use will not snap back to what it would have been if the city had never required off-street parking,” writes Shoup. He predicts that in a post-parking-minimums world, cities will still take decades to recover because new buildings will still be designed for an auto-oriented landscape.

If that’s the case, we’d better start easing up on parking mandates right away. Heat waves in the Pacific Northwest will only become hotter and more frequent in the coming decades, and what gets built today will remain our built environment for decades. If we truly want to lessen the human toll of heat islands, we should probably stop building more of them.

Mike O'Brien

Thanks, Catie— Well articulated, hope our city planners will consider ways to reduce parking and effectively shade what already exists.

Andy Gray

Good article. In addition to less parking, I wonder if putting up solar panels on the rest would help as well? The panels have much less thermal mass than asphalt on the ground and could put all that space to use generating electricity.

Barbara Stebbins

Great article by Catie Gould! I had no idea that over-large parking lots could have such a striking effect on local temperature–and of course contribute to climate change in general. Reducing parking lot size and replacing it with green space clearly makes sense. Not only to reduce those heat islands, but encourage people to use public transit or non-carbon emitting vehicles.

Cliff Sanderlin

Catie, Thank you for your work! What about requiring the use of pervious materials? In Ireland I saw corridors in a parking lot using gravel and pavers with trees, which were thriving.

Doug Klotz

Surprisingly, even buildings would be better than parking lots. Downtown Portland is not a heat island on the maps, and Dr. Shandas told me that it appears that because of the shade cast by the tall buildings, there’s not as much heat at street level. He said they found similar effects in Manhattan, and other city centers. He mentioned that it could also be those wind currents that tend to develop between closely spaced tall buildings is dispersing the heat. (For comparison, Portland’s Central Eastside industrial district, just east of downtown, which has mostly full-block one-story warehouses, which does show up much hotter than downtown)

Glenn Johndohl

Thank you, thank you, thank you!!!

Am glad you mentioned I-205, which a few local historians argue was the nail in the coffin for a once-vibrant neighborhood, not to mention I-205 added heat and substantial air pollution to Lents.

One of the best articles I’ve read on the impact of car culture on a neighborhood level, and our addictive behavior not to deal with it.

Dan

I wonder if a direct economic disincentive would work. Just as many cities charge by the square foot for stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces, maybe there should be a charge for parking pavement, to at least partially make up for the costs to society and government for higher urban temperatures.