If you position your camera at the perfect angle, wait until the right time of day, and keep a soft focus on the shoreline, you can take a picture of Lake Tapps that creates the illusion of a pristine lake in the shadow of Mount Rainier, its edges crowded with Douglas firs and Western Red Cedars.

That is exactly how the reservoir appears on the website of the Cascade Water Alliance (CWA), the coalition of Seattle suburbs that banded together to purchase it from the gas and electric utility Puget Sound Energy.

The 2009 purchase made Lake Tapps the first major new drinking water supply in 50 years in Washington State. The image of a wilderness lake fed by pure mountain streams might apply to Chester Morse Lake and the Tolt Reservoir, the two large reservoirs that currently supply water to Seattle and its suburbs, but applying it to Lake Tapps is either false advertising, self-deception, or some combination of the two.

In reality, Lake Tapps is a time bomb with a 30-year fuse. It offers a cautionary tale of how climate change might jeopardize our water supplies, even in the water-rich world of western Cascadia.

FIRE AND WATER: The Backstory

The notion that it would be easy to turn Lake Tapps into a reliable source of drinking water began unraveling in 2015. The previous fall, the CWA drained the lake and completed a list of long-overdue infrastructure repairs, and the group’s leaders had reason to feel good when everything finished ahead of schedule.

But climate change is not kind to plans built on data from the past.

To understand what that future might hold for Lake Tapps, we need to understand the history of Seattle’s water supply. That story begins—and may end—with fire.

On a June afternoon in 1889, John E. Back set a pot of glue on a stove in the Seattle woodshop where he worked. Around him, the city was swelling. In the preceding decade, the population grew by 1,100 percent—roughly 35 times the rate of today’s boom—creating a mad scramble for housing and resources. The city’s builders threw up wooden buildings as fast as they could manage. For water, the young boomtown relied on a handful of private companies operating a hodgepodge of wells and small reservoirs.

Back, described in newspapers as hapless and of “mediocre intelligence,” later recalled putting the glue on the stove, where it was left until it caught fire. He told a reporter he tried to douse it with water but instead caused a steam explosion which sprayed the shop with flaming glue. Within minutes, the fire engulfed the building. Firefighters aimed streams of water at the growing inferno, trying to save the building, then the block. Before they knew it, they were fighting for the survival of a city made of kindling.

Though Back caused the first flames, the Great Seattle Fire was years in the making. This combination of too much wood and too little water set the stage for disaster.

Half an hour after the fire started, the entire block was ablaze. More and more men braved the scorching heat to aim hoses at the fire, and there was a moment when it seemed they might save the rest of the city.

Then, the water ran out.

Residents of the waterless city could only watch it burn. Twenty-five city blocks, the heart of the city’s downtown, were reduced to ash before it ended. A month later, Seattle voters passed a referendum to create an entirely new water supply, giving it 97 percent of the vote. Land and water were cheap commodities in nineteenth century Washington, so buying a watershed high in the pristine wilderness of the Cascades, damming a river, and running 20 miles of pipeline was a straightforward process, cost was not an issue. Without water, the city could not exist.

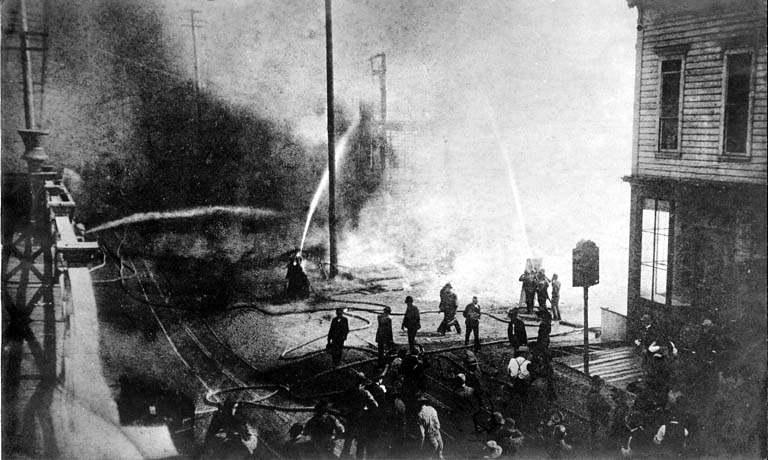

The Great Seattle Fire

LAKE TAPPS: SOFT FOCUS

Today, more than a hundred years after the fire, Chester Morse Lake, which sits behind that dam on the Cedar River, still provides 70 percent of Seattle’s water. A second dam, built in 1964 on the nearby Tolt River, provides the rest. In 1982, the water supply was so abundant that Seattle agreed to share its surplus with major suburbs for the next 30 years. But, when it comes to water, 30 years is an eye blink.

Signing the contract, the Eastside cities knew, only bought a little time. A new water project typically takes at least 20 years to bring on line. Decision-making, purchasing, permitting, and construction are long, slow, expensive propositions. Three decades is tight timetable.

The steady growth of Seattle’s population also meant that, at some point, Seattle would turn off the taps. No one could say for sure when that would happen—it seemed entirely possible that Seattle would extend the contract, but nothing was certain.

(Click and drag the line in the middle of the images below to see a satellite image of development around Lake Tapps in 1984 compared to 2016.)

So the cities of the Eastside banded together to plan a response. After some fits and starts, eight major suburban cities formed the Cascade Water Alliance to address the problem. But it was 1999, not 1889—wandering into the mountains to dam a river was not an option.

The CWA’s members considered drawing from either Lake Washington or Lake Sammamish, two large water bodies near Seattle, but both are relatively polluted and surrounded by some of the region’s most expensive homes. Trying to operate them as reservoirs would create potential operational and political nightmares. So, the CWA scoured the region for a place to build a new reservoir. But there was a reason more than 20 years had passed without construction of a major new dam in Washington. They even explored the possibility of raising the height of the dam on the Cedar River. Luckily, a solution dropped into their laps: instead of building a new dam, they would repurpose one of the oldest dams in the state.

The dam (or, more precisely the series of 15 dams) dates to 1911, when a group now known as Puget Sound Energy looked at a cluster of four spring-fed lakes nestled in the forests and farms of southeast Seattle and imagined a single, vast reservoir. By inserting two-and-a-half miles of dikes into the existing landscape, they outlined the edges of Lake Tapps. They filled it by constructing twelve miles of flumes to divert water from the White River. The resulting water would run through massive pipes to a power plant before rejoining the river.

Eighty years later, just as the CWA was growing thirsty for a solution, Puget Sound Energy was running into permitting trouble with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. After wrangling with the agency for the better part of a decade over a relatively small power plant, Puget Sound Energy was about ready to throw in the towel on Lake Tapps.

The fact that the utility company might be ready to unload one of the largest reservoirs in the state precisely when the CWA was hunting for a new supply of drinking water must have seemed too good to be true. Here was water from a river that began as glacial meltwater on the flanks of Mount Rainier and flowed through protected National Park and National Forest Land. The huge reservoir could provide 65 million gallons of water a day for the cities of the CWA.

At a glance, in a filtered through the trees, silhouetted against a sunset kind of way, it was a dream solution. But when you bring up the lighting, sharpen the focus, and look at Lake Tapps with a cool eye, it has the makings of a nightmare.

LAKE TAPPS: REALITY CHECK

A dream solution is a dam in the foothills of the Cascades on a river fed by a watershed entirely under your control. A water supply so pure, you don’t even need to filter it. Just screen out the leaves and twigs, add a few chemicals, and you’re good to go. That is the Chester Morse Lake. The shoreline of Lake Tapps, on the other hand, is not lined by cedars and Douglas firs but instead hundreds of houses with lush green lawns and individual septic systems. And a boat launch. And a golf course. The White River flows through cattle farms. The lake fills with motorboats every summer. There’s even potential for local industries to contaminate the surface and groundwater flowing into the lake. Not to mention, there’s runoff from the roads that ring the lake. While none of that matters when the water is simply running through a power plant, drinking water is a different story.

Shoreline of Lake Tapps, a reservoir built more than 100 years ago. Though the lake is now used for recreation, a power plant and a host of other purposes, there are plans to eventually use it for drinking water, too. Photo by Bob Morris, used with permission.

And then there’s the politics. When it first filled in 1911, Lake Tapps didn’t look so different from Chester Morse Lake. In the sparsely populated, pre-automotive world, the lake that was thirty-six miles from Seattle and eighteen miles from Tacoma wasn’t useful for much beyond timber and fishing trips. But the post-war population boom changed that. Land values soared, and since no one was drinking the water, Puget Sound Energy had no compelling reason to keep the land. But the utility still made sure to protect its interests. All the contracts to developers in the 1950s gave Puget Sound Energy leaders the right, whenever they felt like it, to walk away from the lake and leave the homeowners high and dry—literally. The clause was largely forgotten for sixty years until talk of selling the lake started springing up. Suddenly, nothing mattered more than the details in those decades-old contracts.

At the same time, the surrounding towns of Buckley, Bonney Lake, Sumner, and Auburn took notice. These relatively small cities suddenly had Bellevue and its neighbors reaching a giant straw into their watershed. Auburn and Sumner needed water, Buckley was worried about its groundwater, and Bonney Lake, which encompassed all the homes on or near the lake, depended on Lake Tapps for its existence.

Even the White River, the source of Lake Tapps’ water, was politically entangled. Federal treaties guarantee fishing rights in the river to both the Puyallup and Muckleshoot tribes.

It’s a daunting task to provide drinking water under the close scrutiny state and federal health and environmental agencies, particularly from a multi-use water source like Lake Tapps. On top of that, the CWA needed to find ways to appease anxious local governments, mollify angry homeowners, and keep the tribes (and the salmon) happy.

The Lake Tapps Homeowners Association arrived at its first meeting on a war footing and the CWA knew it. They made a 30-year commitment to keep water levels in the lake suitable for boating from Memorial through Labor Day. The CWA also agreed to work with local communities to ensure operations would not affect residents’ water supplies, and it promised the tribes that it would leave enough water in the White River for the salmon fishery.

Initially, it appeared CWA leaders did an astonishing job of navigating the political minefield. But like those photographs of the lake, looks can be deceiving. Under the terms of a 2003 agreement between the city and CWA, Seattle agreed to supply some or all of the CWA’s water until 2053—another 35 years.

That means three things. First, the 30-year commitment to the homeowners is meaningless. It will expire before the CWA needs to draw down lake levels in a serious way. Second, by 2053, the residents who negotiated the deal with the CWA will be retired, if not deceased. Third, by the time the CWA starts to use the lake for drinking water, it is likely that the changing climate will have made all of the predictions about managing the lake obsolete.

Those predictions bring us back to the spring of 2015, almost a year after crews drained the massive reservoir and completed their lengthy punch list that included everything from repairing fish screens to replacing miles of concrete flume that carries water from the White River. With the work done, all that remained was to divert water back into the lake.

A view of Lake Tapps’ north arm in 1989. The White River Hydroelectric Project was completed in 1911. This photo is from Puget Sound Power and Light Company and is maintained by the Historic American Buildings Survey. Image by Brian C. Morris, Puget Power/Historic American Buildings Survey

Models created by the engineers and hydrologists working with CWA showed that, even under the lowest flows ever recorded, the White River would still refill the reservoir by Memorial Day. The prediction was based on solid science, with more than a century of carefully collected and collated data. But buried in the calculation was an assumption that the future would always look like the past.

The year 2015 was the warmest ever recorded in Seattle. As a whole, it was not a dry year—it was actually wetter than average—but a warm winter meant mountain snowpack, which normally filled the river in the spring and steadily fed it through the dry summer, just wasn’t there. Then, the springtime rains that historically turned the state’s rivers into raging torrents didn’t come. The combined rainfall for May and June was the lowest ever recorded.

Despite all predictions, Memorial Day came and went and the lake was far from full. On July 4, residents of the homes that line the banks were still staring out across Lake Tapps’ mudflats.

The lake eventually filled by mid-July. At best, CWA was cursed with a moment of astonishingly bad luck. But what if it was not an anomaly? Six years earlier, an international panel of experts, convened by the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington, predicted that the state would see three major changes in its climate:

- Warmer average temperatures

- More total precipitation

- Lower summer precipitation.

The year 2015 made them look pretty smart.

The Climate Impacts Group report made one other prediction: hotter, drier summers, it warned, would increase the risk of forest fires. Washington is a state where forest fires are simply expected in the summer, but it had never seen a fire season like 2015. By the end of the year, over a million acres had burned, mostly in the dry, eastern part of the state.

In other words, 2015 matched the predictions of the climate change models and raised the possibility that bizarre year could become the baseline for what the future could look like. If so, the challenges to strike the delicate balance between politics and water quality, daunting under the old normal, could be far worse for Lake Tapps than anyone imagined. The next two summers put an exclamation point on this concern.

Satellite image of Washington state Aug. 22, 2015, with smoke covering most of the Puget Sound region. Image taken by the NASA Terra satellite and the MODIS instrument onboard. Image by LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team, GSFC, NASA

The year 2016 was not the hottest on record. It was the second hottest. In August of that year, temperatures stretched into the 90s and the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department started getting complaints of people becoming nauseous after swimming in Lake Tapps. Water samples showed the presence of a microcystis, a photosynthetic bacteria often called toxic algae. This primitive organism produces four extremely potent toxins that can cause skin irritation, nausea, weakness, liver damage, and, at high enough levels, death. It blooms in the presence of high temperatures and elevated nutrient levels. Steady, heavy rains from late fall through early spring washed nutrients from nearby farms and lawns into the lake. Combined with the hot summer weather, Lake Tapps turned into a perfect culture medium for microcystis. The conditions in the watershed matched climate predictions and the results were profoundly worrisome. The health department closed the lake to swimming. If CWA had been providing drinking water, the closure also would have extended to the water treatment plant.

Natural Northwest forests have evolved to catch water in the winter and hold it through the summer. Chester Morse Lake is surrounded by dense forests and managers there don’t worry much about the heavy nutrient loads during wet winters. Only one element could rattle confidence in the lake’s resilience: fire.

Fire can destroy natural forest buffers, which, in turn, exposes water to heavy runoff and nutrient loads. Watershed managers were able to take comfort for more than a century in the notion that western Washington is too wet to burn. Then along came the summer of 2017.

Taken as a whole, it wasn’t a dry year. Seattle saw 48 inches of rain, 10 more than average. But climate change is about extremes. Seattle went a record-setting 55 days without rain that summer. And, in August, with temperatures reaching into the 90s, the smoke of forest fires descended on Seattle like a vision from an apocalyptic future.

The number of acres burned did not compare to 2015, perhaps, in part, because the most susceptible forests were already burned. What was remarkable, however, is which forests burned. As the US Forest Service put it in its report on the fire season, “large fires occurred in unexpected places, which are typically considered too wet and temperate to burn, or at least burn readily.”

The fires did not reach Chester Morse Lake but if climate change progresses as predicted, that could change. Fire, which gave birth to the Seattle water supply, may be among the greatest threats to its long-term viability.

WATER AND CLIMATE CHANGE: The Teeth of the Shark

The full story of Lake Tapps remains to be told, but its beginnings suggest a cautionary tale about water and climate change. Like the Seattle area, most of Cascadia’s cities—indeed, most of the world’s—face growing populations, increasing development, and diminishing alternatives for new sources of freshwater. Water conservation can help reduce the need for new sources, but ultimately, growing demand will force most of these cities to find new water.

Scientific models suggest extreme temperatures of 2015 won’t just be the new normal—they will be the new cool.

The best options for fresh water are gone and alternatives are hard to come by. There are no more protected watersheds within reach of major cities. Almost all of the large cities of Australia are turning to salt water as are many less arid cities, such as London. Other cities are looking at recycling wastewater into drinking water. The CWA did not have to go to those lengths, but even without climate change, Lake Tapps is far from ideal as a source of drinking water, from a technical and a political perspective.

If we were dealing with a stable climate, a suboptimal solution like Lake Tapps could work, but evidence suggests we are not. Extreme weather patterns of the last three years offer a glimpse of what might be the potentially devastating impact of climate change on the quantity and quality of water supplies of Cascadia. Newer, less protected water sources such as Lake Tapps are at the greatest risk. Increased precipitation during the rainy season will flush more nutrients and contaminants into surface water, decreasing water quality. Warmer winters will reduce snowpack, which will diminish the water supply in the summer. Hotter, drier summers will further test the water supplies by decreasing streamflow, increasing evaporation, and increasing algal blooms. Higher risk of fires may even put our most pristine waters at risk. And we are just at the beginning of climate change. Scientific models suggest extreme temperatures of 2015 won’t just be the new normal—they will be the new cool. By 2080, the predicted rise in average annual temperatures relative to historical averages will be two to five times the increases we saw in 2015.

None of this is to suggest that the CWA was unwise to purchase Lake Tapps. More likely, they were prescient. Options would have been worse had leaders waited 20 or 30 years until Seattle turned off the tap. But it is time to think carefully about how we use water, to look for innovative ways to reduce demand by reusing wastewater locally and to conserve water in all the ways it is used. And time to stop lollygagging on the transition to a carbon-neutral economy.

If a region as waterlogged as western Cascadia faces the sorts of water challenges I have just described, everyone is in trouble. Climate change may force us to throw out our assumptions about water supplies. As Canadian climate scientist, James P. Bruce, once said, “If climate change is a shark, water is its teeth.” By mid-century, it seems, we will be squarely in its jaws.

Robert D. Morris, MD, PhD, is the scientific director of Eco Logic Consulting, a senior sustainability consultant to Bloomberg BNA, and the senior medical advisor to the Environmental Health Trust. He has taught at Tufts University School of Medicine, Harvard University School of Public Health, and the Medical College of Wisconsin as well as serving as an advisor to the EPA, CDC, NIH and the President’s Cancer Panel. His work has been featured in the New York Times and the London Times, and on Dateline NBC and the BBC. His first book, The Blue Death, received a Nautilus Gold Award and was named one of the Best Consumer Health Books of 2007 by the American Library Association. He lives in Seattle, WA.

Canyon Man

More damn pressure on my first amendment rights. It is getting worse all the time. All I wanted to say was that it has always been a source of wonderment to me that the New City guys had the vision to do what they did. I have spent a little time in three American cities: New York, Seattle, and New Orleans. Water out of the tap in New York is damn good, New Orleans’ barely potable. I drank it all in the spirit of the theory that exposure makes you less vulnerable. I continue to drink out of the odd mud puddle to become one with the local bacteria. I beat all the odds ten years ago. Let’s see how it goes.

Bob Morris

Well said. City’s such as New York, Boston, Seattle, and Portland, which established reservoirs in relative wilderness back when such a thing was possible, are far ahead of cities such as New Orleans, St. Louis, and Washington DC that draw from large rivers which are inevitably contaminated by everything from farm runoff to treated sewage and industrial wastewater.

Bob Morris

Well said. City’s such as New York, Boston, Seattle, and Portland, which established reservoirs in relative wilderness back when such a thing was possible, are far ahead of cities such as New Orleans, St. Louis, and Washington DC that draw from large rivers which are inevitably contaminated by everything from farm runoff to treated sewage and industrial wastewater.

Patricia W Treff

Excellent information. Thank you. We moved to Bonney Lake from the Midwest July 2017 and bought a house on Lake Tapps. It is hard to imagine that Lake Tapps is a logical water source for communities so far away. Is groundwater not an option for Seattle?

Bob Morris

Some of the suburbs can rely on groundwater, but it can’t provide the volume of required for Seattle.

David Plummer

Great article!!

1. If there’s any thought of a slight update, perhaps the author (or Sightline staff) could add a short description of what CWA has to do to actually get Lake Tapps water to the closest water transmission line (it appears that Tacoma’s No. 1 or No. 5 would work). Unless there’s some other way for them to get the Lake’s water into the regional system …?

2. Is it OK to reference the link to this article in an LTE?

lanette

Great article, however, one note I would like to make is there is no reference to the decline in water allowed to flow through the lake, and the possible impact this has on the quality of water within the lake.

Part of the negotiations, and agreements, made during the 12-period of “Saving Lake Tapps” was that the 2000 cubic feet per second that was previously allowed to flow into Lake Tapps was ‘taken’ down to only 250 cubic feet per second. I believe even the Washington State Department of Ecology said a minimum of 500 cubic feet per second would be necessary to maintain healthy water in Lake Tapps. It doesn’t take a lot of calculating to understand how the flow and flush of water, or lack thereof, affects the quality of water in a contained area. When the State of Washington agreed to allow the flow of only 250 cubic feet per second into Lake Tapps, in spite of studies that suggested twice the amount, they knowingly agreed to create a lake body of contamination. Climate change, natural or otherwise, is not the reason the water of Lake Tapps is contaminated. (actual flow may be different on a daily basis) #TheTruthAboutLakeTappsWaterQuality

Eric

I completely agree– it’s the same reason why a standing puddle of water is so much dirtier than a running stream. Water flow is vital to the health of any body of water, and given the recreational use of Lake Tapps it seems like this would have been addressed properly.

Lanette, do you know if there is any recourse the average citizens of Lake Tapps (that use it recreationally for swimming or fishing) have to improve our water quality?

Mike perusse

Does lake tapps supply the new city of tewela?