Two years from next month, Portland’s regional government plans to ask voters for about a billion dollars to help build the first modern light rail line through the region’s most exclusive quadrant.

The “Southwest Corridor” project through Portland’s mostly well-off (but poorly connected) southwest neighborhoods could become a new model for the Pacific Northwest in how to improve housing and transportation at the same time.

Alternatively, it could become a model of how to utterly fail at doing so.

On Thursday, Portland’s city council seems certain to approve a toothless document packed with good ideas for mitigating one of the risks of that rail line: that it’d help trigger price increases that force 12,000 low-income households out of Southwest Portland’s “naturally occurring affordable housing”—that is, the old, intact and relatively cheap market-rate apartment buildings scattered around the Barbur Boulevard area.

Notably, the plan recommends buying a bunch of those buildings and converting them to public, rent-regulated housing at their current prices. It’s a great idea that nobody objects to, at least until someone asks them to help pay for it. (Hint: we should pay for it.)

But one of the reasons Portland’s Southwest Corridor housing strategy is so uncontroversial is its toothlessness. Specifically, it fails to sink any teeth into anything that might change this:

That’s what the housing options look like today two blocks north of one of the most important stations of this proposed $2.8 billion rail line, Barbur Transit Center.

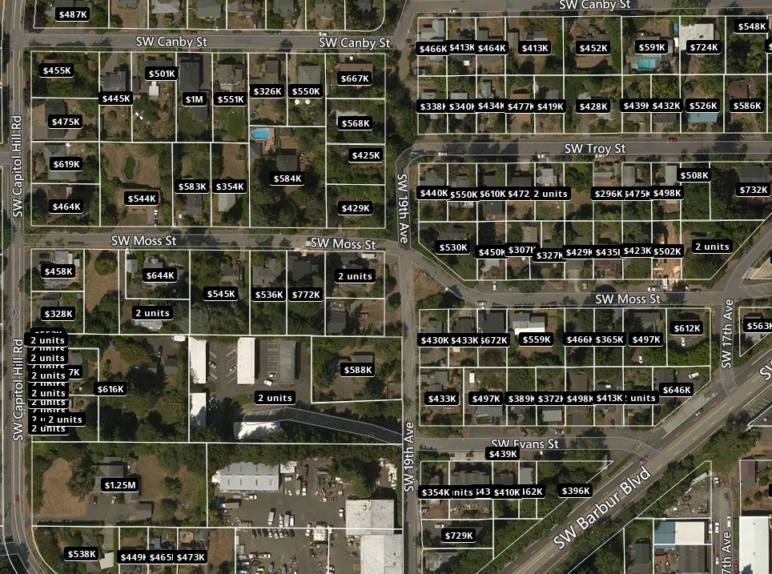

Or, here’s the housing selection immediately north of the station at Barbur and 19th:

I just showed you pictures of about 200 houses on 60 acres, all of them within a future five-minute walk of a massively expensive new rail line to downtown and almost all of them requiring mortgage payments of $2,400 or more—which makes very few of them affordable to a family of four making the Portland area’s median income of $81,400.

And these are the prices before a rail line has even been built.

The strangest part of the images above is that these home prices are essentially mandatory. On most of these lots, dividing the land into so much as a duplex would be illegal.

If that’s not a recipe for luxury housing, I don’t know what is.

In defense of Portland’s housing strategy document, it does identify this issue. All told, apartment buildings are illegal on 48 percent of the land near Portland’s potential stations, it notes. Upzoning this currently exclusive land to allow four-to-six story buildings would eventually make the rail line useful to many thousands more people while also triggering the affordability requirements that kick in for buildings with more than 20 homes.

Here are the document’s proposed remedies: “a corridor-wide station area planning process, beginning in select station areas using a fair housing and health equity lens” and followed by “additional affordability goals and incentives” to get below-market housing built.

In other words, Portland should legalize apartment buildings near its future rail stations, then find offsets that ensure a meaningful number of those new homes are affordable to people who truly need to ride the train.

This isn’t rocket science. And, unlike purchasing the corridor’s old apartment buildings (which, to recap, we the public should also do) it might not even require new dedicated tax revenue.

But it would require big changes to the neighborhoods in the pictures above. And Portland, for all its good intentions, currently has no timeline for making them.

Shawn Fleek, a spokesman for OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon, told me Tuesday that the city recommendation to upzone these station areas into mixed-income apartment buildings with community benefit agreements could easily be forgotten, just like “any of those clauses that is going to benefit low-income communities and communities of color.”

“We’re looking for definitive material gains and not just empty promises,” Fleek said.

Every city in Cascadia needs better transit, and any proposed rail line has promise. But unless we make it legal for lots of people to actually live near rail stations if they want to, that promise will indeed be empty—for most of us.

JB

Just no. Stop pathologizing the basic need for space. Maybe work on population problems first instead of forcing people to live in tenements. Maybe poor people also want to live in a single family house with room for enjoying some private space.

Mito

Because truly, the poor as well as the rich can apply for a half million dollar mortgage.

Chris I

So, let me get this straight. You’re arguing that we should work on “population problems” instead? Just what exactly is your “final solution” to this problem? And how do you expect urban planners might be involved in said solution?

Fred

I don’t agree with JB’s comment about “population problems,” but I do agree with the comment about “pathologizing the need for space.” You need to understand that your diagram of houses is not just a planning construct – actual people, and families, live in those houses. They *want* to live in those houses and love living in them, and have worked their entire lives to afford to live there (I am one of them). If you require bulldozing our neighborhood to bring the MAX line up Barbur, then I’ll be right there with my neighbors to vote against the MAX.

Why do you have to pit people and interests against one another? I suggest you should want to bring about gradual and incremental change, and not try to blow everything up just to bring the MAX line to Barbur. Sheesh.

Michael Andersen

To be clear, I’m not arguing in this piece that anybody needs to leave a home they love; that every lot in any neighborhood should be immediately transformed by fiat; or that nobody should be allowed to spend hard-earned money on a nice big home if that’s what they want.

What I’m arguing is that we should not REQUIRE big freestanding homes to be the ONLY option for living in this area.

Lenny Anderson

I served on the Interstate MAX CAC as well as the Interstate URA CAC. We put language in the latter’ charter in 1999 to protect at risk residents and businesses; we participated in station area visioning/planning sessions to help insure that housing, business and community goals were clear. But the last folks to get on board was CoP’s Bureau of Planning (& Sustainability) with the needed zone changes! Rather than having those changes in place before the first Interstate MAX dirt was turned in 2000, that came years later. New Seasons put a parking lot at the Rosa Parks MAX Station with no housing. Without zone changes, and financial incentives for dense and affordable housing within station areas of a SW MAX, it is a doomed effort and should not be funded.

Dave

I’d suggest that it’s time, in the name of shortening commutes/making distance drives for housing affordability obsolete, to set finite limits on rents and on the value of properties. Look, we have to change big time to solve some big problems and it may be time for overtly Marxist housing policies. There has to be a limit to what a patch of dirt or a set of walls is worth.

Mary Vogel

I found Lenny Anderson’s comment above very enlightening. And I agree wholeheartedly with his statement: “Without zone changes, and financial incentives for dense and affordable housing within station areas of a SW MAX, it is a doomed effort and should not be funded.” If even a community in Virginia could do this many years ago for their new heavy rail stations, Portland, at least, should do it NOW! Rather should have done it during the planning process–along with land banking.

Casey

You don’t want to bring an environmently friendly public transportation to a region of several hundred thousand people, because we can’t fill one small already developed portion up with condos?

I get it; if we are building this sort of investment we want it to make it as beneficial as possible, but you are so focused in on one small portion (which happens to be fine as it is) that you can’t see the greater good for the entire region.

Casey

I’m just glad people didn’t stop the blue line from being built all the way out to Beaverton and Hillsboro simply because there were already a bunch of single family homes up in the Portland West hills along the way.

Michael Andersen

Those homes aren’t a three-minute walk away from the rail stops, though.

Doug

And BPS, often, will claim they don’t have enough funding/staff time to do an upzoning project now. They’re still doing projects now that should have been done during the Comp Plan, but didn’t have the “capacity” to do, like rewriting the multifamily zoning. And though they’re now doing that, it doesn’t include remapping such zones, which is another, further project to be done.

Looking at zoning along the Southwest Corridor is a proposed project, but it will only cover the West Portland Town Center, and South Portland neighborhood (I think). They don’t have funding to do every station on the line, which is what they should be doing.