One of North America’s biggest new ideas for greener transportation is spreading north.

A year after a pair of California state senators drew national attention with a proposal to lift apartment bans from all residential land within a quarter mile of frequent transit, Oregon has a similar bill of its own.

Senate Bill 10, which was introduced last week, had its first public hearing Monday, February 25.

This isn’t the first time the idea of state-led housing legalization, focused specifically around transit, has come to Cascadia. But it’s definitely one of the most ambitious.

SB 10 is barely over one page long, but it’s quite a bill. It would legalize hundreds of thousands of potential future homes, almost all of them in three urban areas: Portland, Eugene-Springfield, and Salem. The buildings it’d legalize—though not, of course, guarantee would or could be built—range from two-story townhomes in small cities to 6-story apartment blocks near Portland-area light rail stops.

Also, for all projects less than half a mile from rail or other frequent transit, the bill would strike down all mandatory parking quotas.

There’s compelling logic to it. Oregonians have spent billions of dollars on their mass transit systems and spend more than a billion more every year. Why not let people live near them if they want to?

Similarly, what better place to allow new below-market housing intended to serve Oregonians who are particularly unlikely to own cars?

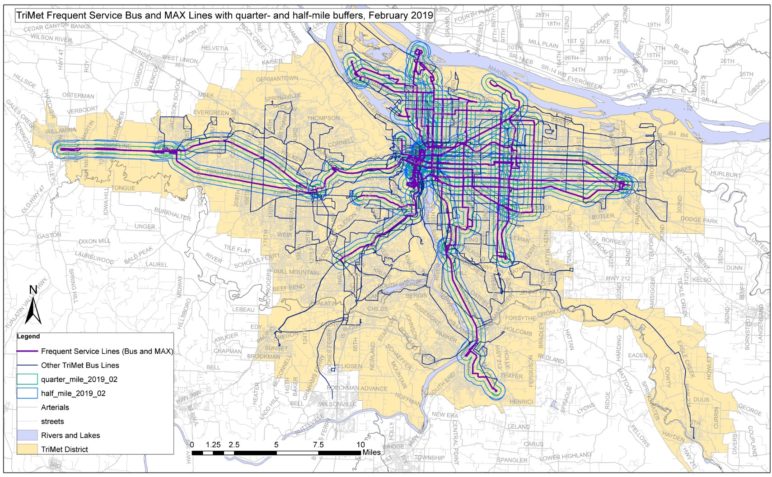

Greater Portland’s regional transit agency TriMet has mapped the land in the Portland area where zoning would be somehow affected:

But what sort of housing, exactly, would the bill legalize?

SB 10 isn’t clear on the technical but important question of whether its new density limits refer to net or gross acreage—that is, whether undevelopable land like streets is included in the ratios. And the office of Sen. Peter Courtney, who sponsored the bill, didn’t respond on the record to a request for clarification last week. But because of the way the regulation is written—applying at the lot level rather than setting average density throughout an area—the intent is probably to refer to net density.

Below are a series of slides, created by Seattle-based urban design firm GGLO Design unless noted, showing roughly what scale of housing the bill would allow where. (Thanks to my colleague Dan Bertolet for compiling all the images below for a 2009 post on his personal blog, before his current stint at Sightline.)

Keep in mind that the law would apply equally to public and private projects, market-rate and below-market homes.

In Portland-area cities above 10,000 residents

(Here’s a list of Oregon cities by population.)

Within a quarter-mile of a light rail station: 140 homes per acre. So, somewhat less than the building below, which has 162 homes per net acre.

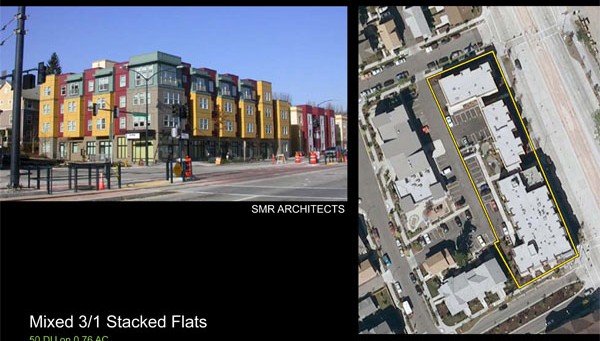

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a current station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 75 homes per acre. So, a bit more than the building below, which has 66 homes per acre.

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 45 homes per acre. So, a bit denser than this, which has 41 homes per acre:

In cities above 10,000 residents in one of Oregon’s seven metropolitan planning organizations

(Here’s a site that gives a list of Oregon’s seven MPOs. It’s basically the 10 biggest urban clusters, including some suburbs of Longview-Kelso and Walla Walla, Wash. Here’s a list of Oregon cities by population.)

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a nearby station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 50 homes per acre. So, somewhat denser than the below (which you’ll notice is also the closest example for the scenario immediately above), which has 41 homes per acre:

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 25 homes per acre. So, about the same as this fiveplex, which offers 27 homes per acre:

In cities above 10,000 residents that aren’t in one of Oregon’s seven mpos

At the moment, there don’t seem to be an such cities in Oregon, unless one such as, say, Woodburn were to sharply increase its peak-hour transit frequency. So the below images seem to be theoretical, for now.

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a nearby station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 25 homes per acre. Again, that’s about the same as this fiveplex, which offers 27 homes per acre:

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 14 homes per acre. That’s exactly the density of these two-story townhomes:

Again: Senate Bill 10 wouldn’t require any building to be replaced. It wouldn’t guarantee that it would be profitable for anyone to actually build anything pictured above. But it would make it possible for buildings like the above to exist. Today, in many areas, that’s illegal.

“Smart growth” like this would sharply reduce energy bills, infrastructure expenses and sprawl

If this bill passes, and if buildings like these are eventually built, what would the effects be?

A report released last year by the new national organization Up For Growth, Housing Underproduction in Oregon, offers a partial answer. It estimated that in the wake of the Great Recession’s collapse in homebuilding, Oregon is 155,000 homes short of its long-term needs. The report (authored by economic consulting firm ECONorthwest) then floated two scenarios for building new homes:

- A “more of the same” scenario that assumed Oregon would continue building detached homes, low-rise attached homes and towers at the same ratios as its past;

- A “smart growth” scenario that assumed Oregon would concentrate new homes near jobs and transit, as envisioned by Senate Bill 10.

According to ECONorthwest’s calculations, the “smart growth” scenario would (compared with “more of the same”) reduce the rate of sprawl by 81 percent; reduce auto miles traveled by 34 percent; and reduce public infrastructure spending by 89 percent.

Building many more homes near transit would save money. It would help preserve the global and local ecosystem. It would, in combination with necessary public support for lower-income Oregonians, help keep everyone housed who needs to be.

Should what’s good also be legal? That’s the question SB 10 asks of us.

Tina

I wonder if the bill will also address shopping in high-density neighborhoods near the rail lines. To truly live without a car (or for a family to drop from 2 cars to 1), we need not just housing but services. The Elmonica station on the MAX blue line in Beaverton/Hillsboro is a great example. There is a ton of high-density housing all around the station. There is a giant Tri Met park-and-ride lot. There are a few (less than 10) small shops. There is a giant vacant lot. There is also no grocery store, and no shopping that could enable a person to truly live without a car. Where is the will (and the help) to build services IN the transit-friendly neighborhoods also near the rail line? Houses and apartments on their own next to the trains won’t do it.

Paul T CONTE

The basic (but not necessarily publicized) main purpose of MAX is to reduce urban center congestion by commuters. That may also reduce average Vehicle Miles Travelled, which is a good thing. But this fantasy that a large number of the occupants of expensive apartments and condos on a MAX line are not going to own and use cars is unsupported. It takes an incredible density and mixed-use to support car-free households. I lived in the center of Washington D.C. for awhile in an older row-house (converted to rental units) without needing a car. But when I moved out to Roslyn, just across from Georgetown, there were thousands of apartments, but commercial was strip development, which required a car.

In contrast, I lived in a rented room in a single-family, detached house for two years without a car, and it was fine because it was safe and convenient to use my bicycle (as a young, healthy individual).

Diminishing car use is a complex and challenging problem, and SB 10 (along with HB 2001) are so simplistic, they aren’t going to help at all. On the face of it, “one-size-fits-all” with no fore-planning is absurd.

Michael Andersen

Good points, Tina. I’ll say here what I said on Facebook: It’s a chicken/egg problem. TriMet can’t begin to justify frequent service buses (let alone the necessary grid of them) until the density of an area is roughly 2x that of the lower-density parts of Portland. There just aren’t enough potential riders. Same with walkable shops (though not enough commercial zoning in some areas is a problem for that too).

If we wait to legalize housing until after we have transit and walkable retail, then we’ll never have either and we’ll keep subdividing the Willamette Valley (and/or driving up home prices) instead. We’ve got to start the process somewhere, in my opinion. So we should be tapping private investment in housing while we can, and using the tax dollars and purchasing power that are created to pay for the buses and shops that are also needed in Elmonica etc.

Also: my family rents an ADU that’s a five-minute walk from a grocery store and a 7-minute walk from the 60th Ave rail station, where trains arrive in both directions every five minutes all day. I would love for people to be allowed to live above us. But they’re not. Portland’s zoning process has failed the thousands of people who would like to live in my neighborhood but can’t.

In the forseeable future, this bill would be much more likely to create housing in my area than in lower-amenity areas like Elmonica. Allowing it in the lower-amenity areas too is a way to prevent future shortages from materializing. (But could, admittedly, have other downsides.)

Paul T CONTE

Please pass the Kool-Aid!

SB 10 went to public hearing yesterday, and there was overwhelming opposition, including League of Women Voters Oregon, Portland Planning Department, Oregon Chapter of the American Planning Association, and many more.

I contacted Courtney’s office and spoke with a “policy director,” who couldn’t answer the most basic questions. In addition, no one has any data or even a good guess on the geographic scope or impacts in the top ten population cities in Oregon (except partially for Portland).

The provisions in Section 2 Subsections (3)(a) and (b) would apply to Eugene, and would require a maximum allowable density of 50 or 25 residential units per acre if within one-quarter mile or one-half mile, respectively, of a priority transportation corridor.

In Eugene, this would encompass the EmX bus rapid transit corridor along W. 6th and 7th Aves., as well as numerous main streets, such as Coburg Road, that have multiple bus route. Both of these “corridors” are abutted by older, fully built-out, low- and/or medium-density residential areas within a half mile on both sides. There are hundreds of single-family homes, as well as plexes and medium-scale apartments.

Here are the unclear and/or ambiguous terms and provisions in SECTION 2 for which I asked clarification, but which staff could not answer:

(1)(c) Bus routes with service every 15 minutes or less during peak commuting hours.

* Does this mean “at least one bus route with service every 15 minutes or less during peak commuting hours,” or does it mean “any route segment” along which there is a bus every 15 minutes or less during peak commuting hours.

* How are peak commuting hours determined.

* Is this criterion met only if the bus route provides service every 15 minutes or less during the entirety peak commuting hours. Or is the criterion met if the 15-miunute-or-less service occurs during some portion of peak commuting hours. Is it met if the 15-miunute-or-less service occurs only doing morning or evening peak commuting hours, but not both.

(3) Within areas zoned to allow residential development …

* Does “zoned to allow residential development” mean all zones that allow any form of dwelling, either “by right” or “conditionally? Or is the scope more narrow; e.g., zones whose primary purpose is “residential.” (Note that SB 1051 and proposed HB 2001 use different language, i.e., “zoned for ….”

(3)(a) and (b) 50/25 residential units per acre if within one-quarter/one-half mile of a priority transportation corridor.

* What are the endpoints for the two distances?

— E.g., On the corridor, is it any part of the corridor right-of-way; any part of a bus stop/station; etc.

— E.g., On a lot, is it to any point on the lot boundary; to any point on a dwelling; to the front door of a dwelling; etc.

— How are cases, such as the West Eugene EmX alignment treated, when the two directions are at least a block apart. Thus, a site that is withing 1/4 mile of one direction’s route may be more than 1/4 mile from the other direction’s route.

* How is the distance measured? A direct, horizontal line; a line across grade (e.g., on a sloped area); the shortest walking distance; etc

The intent is to allow wholesale redevelopment of a one-mile wide, undifferentiated swath</I to high-density apartments, including those established neighborhoods that are zoned for low- or medium-density and are within a quarter-mile of a priority transportation corridor.

No wonder even the Oregon APA opposes this idiotic bill.

Paul T CONTE

For anyone who would like more than a bumper-sticker “pitch” for SB 10, I suggest you read the testimony available at:

https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Measures/Exhibits/SB10

If you read it all, you’ll discover that the advocates almost no credible data, instead resting their case on one pivotal assumption: Radical upzoning will produce more market-rate housing and that “supply” will trickle down to lower rents and dwelling prices.

But, as opposing testimony cites in a number of recent and solid research analysis, this action wouldn’t help, but would instead worsen, housing affordability.

It’s also the most egregious rejection of Statewide Planning Goal 1 — Citizen Involvement.

The measure is so ridiculous that I was wondering of “Sightline” would be too embarrassed to advocate for it. Nope.

Evan Manvel

Oregon has 8 MPOs (plus two crossing the border of WA). 🙂

Dave

Land use on private property cannot mitigate congestion because there is no link between land use and transportation mode choice. An apartment doesn’t make people take a train anymore than a house makes people drive–their choices do. The best way to influence choices about travel behavior are not by regulating land uses but by regulating STREET SPACE. Want to cut down on traffic? Charge people for road use by the foot and on street parking by the minute.

We pay to build electrical wires but then have no problem paying for each unit of electrical flow across them. We pay to build water pipes but then have no problem paying for each amount that comes out of them. We have paid to build the roads–but why aren’t we charging for the use of them?

Michael Andersen

You won’t hear any disagreement from me that we need to pay for road and parking space access like any other utility.

The idea that there is no link between land use and transportation choice isn’t accurate, though. There’s an extremely strong link between land use and transportation mode choice.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11116-007-9153-5

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0042098984538

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S136192099900036X

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11116-007-9132-x

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361920997000096

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0966692306001189

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361920998000017

It’s not clear how causal this relationship is — that is, if you plop a random person in a denser environment, independent of other factors, will they automatically become more likely to choose transit? Probably not much. But when we’re talking about whether or not to allow people to choose to live near frequent transit if they want to, we don’t need to worry about selection bias. The whole point is to allow people to self select. Our current laws make it illegal for more than a relative handful of people to live in various areas that are well-served by transit.

Dave

As desperately as academics want to find it, there is no causal link between land use and mode choice. What is it about a house that generates a certain number of vehicle trips? What is it about a business that generates a certain number of vehicle trips? What about a laundromat? It is nothing about these land uses themselves, but rather the choices of people who patronize them.

Let’s take a basic example: Say we have an office of 10 people located in southern California, and an exact clone of the same office on Mt Everest. If land use causes vehicle trips we should see the same number of vehicle strips in both places, right? Of course we are not going to see the same number of vehicle trips in the Himalayas, because what really influences transportation mode choice over land use is surrounding infrastructure context. Build more roads, people drive more.

“It’s not clear how causal this relationship is”

Yes, and it will never be, because the causal relationship doesn’t exist.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01944363.2016.1249508?journalCode=rjpa20

Dave

I’ll add a bit more–in one of the links you provided: “Does neighborhood design influence travel?: A behavioral analysis of travel diary and GIS data” the abstract states:

“An analysis of household travel diary and GIS data for San Diego finds little role for land use in explaining travel behavior, and no evidence that the street network pattern affects either short or long non-work travel decisions. ”

Academics will continue to search for a connection but they are looking into a nebulous world where they will never find any results. The fundamental fact is that Apartment buildings don’t make people ride light rail, just like single family homes don’t make people drive cars.

Look on Google Maps for “Westview at Lincoln Station By Cortland” in Denver for an example—a high density apartment complex adjacent to a light rail line where I would wager the majority of the people still drive for the majority of their trips. This is because as long as transit is less convenient than driving, people will choose the latter.

Paul CONTE

I don’t have the studies at my fingertips, but an intensive California study found what may seem obvious VMT (Vehicle Miles Travelled) is directly related to distance between home and work. Transit should be expected to influence this in certain contexts. (When I lived in Washington D.C., I rode the bus to work when I worked downtown and drove when I worked in Crystal City.) Bus service and congestion were the determinant factors.

Now, here’s sobering additional results: Number of trips per household directly related to household wealth and number of kids. Again, not surprising. Most families aren’t living in Manhattan.

And, local research around the UO neighborhoods. A large proportion of students owned cars, but walked to school (Duh!) However, almost all of them that had jobs to which they couldn’t walk, used their car, not transit; and a high proportion of usage was on weekends for errands and recreation.

It’s a fool’s errand to prohibit parking requirements unless it’s tied to rental agreements to not own a car.

Michael Andersen

I agree, Dave, but like I said – you don’t need to believe land use is the causal factor to think it’s a good idea to make these homes legal – legalizing housing near transit lets people self-select for that location if and only if they want to. If someone doesn’t want to pay a slight premium to live near transit, then no market-rate housing will be developed there as a result of this law.

Dave

No question that it’s a good thing to allow more density–I agree. But not challenging the pernicious and false idea that land use (other than transportation related land uses) can make people choose a transportation choice is sort of like not challenging someone saying “well, not everyone agrees with evolution”…

Paul T CONTE

A recap of the testimony thus far on SB 10.

Read the submitted testimony here:

https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Committees/SHOUS/2019-02-25-15-00/SB10/Details

It is resoundingly in opposition.

I submitted a request for clarifications of numerous unclear or ambiguous terms and provisions and contacted Courtney’s policy director. No response.

I’ve also submitted substantial evidence from credible research demonstrating that the “brute force” approach will not accomplish any good and will do harm. If you’re interested, my testimony is posted here:

https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/164325

Jurisdictions and organizations who oppose the bill as introduced:

* Andy Shaw, Director, Govt Affairs and Policy Development, Metro

* Colin Cooper, Planning Director, Hillsboro

* Eric Chambers, Govt Relations Director, Gresham

* Joe Zehnder, Interim Director, Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, Portland

* Keith Mays, Mayor Sherwood

* Lucy Vinis, Mayor of Eugene

* Mary Vogel, PDX YIMBY; Portland Tenants United; Cascadia Chapter, Congress for the New Urbanism

* Norman Turrill and Peggy Lynch, League of Women Voters of Oregon

* DLCD (while stating “no position,” the testimony identifies critical flaws, which are essentially objections to passage as introduced)

* Tamara DeRidder, Principal, TDR & Associates

The one lonely organization in supporter:

* Jon Bartholomew, Government Relations Director, AARP Oregon

P.S. If you’re a homeowner in Gresham, who loves their neighborhood, be aware that your State Senator (Anderson) referred to you as “NIMBYs.”

Dani Zeghbib

Without by-right form-based zoning, “density” allowances just lead to a bunch of 300-350 sqft microunits, which house fewer humans per square foot than would a 1200 sqft 3 bedroom apartment. And those microunit inhabitants/renters will overwhelmingly be millennial and Gen Z urban professionals who contribute relatively little to the long-term vibrancy of a city. That’s because younger people tend to move to wherever the jobs are, rather than setting down roots and substantively investing in the place they live.

I don’t have children nor do I plan to, but studies show that it’s children who create long-term vibrancy because after they move away for college, they often come back to their hometowns after their own job-hopping stints.

City planning for 20-somethings is short-sighted. It’s like a business choosing to perpetually market to new customers rather than fostering repeat customers — which, as any business owner will tell you, is the most cost- and time-effective way to sustain a business. Or a city.

Michael Andersen

Dani, I think you make a legitimate point that a purely unit-based standard would not be very good. The statute as currently written includes a provision that would create a regulatory standard on questions of height and size – what local height and size limits would constitute an unreasonable restriction on the statutory unit counts?

I disagree with you on a couple points:

– I think you overlook the single largest driver of falling average household sizes: healthy seniors. Not saying that every senior wants to live in a microunit (and again, I strongly feel that a de facto “only microunits” policy would be bad) but lots of seniors would happily live in small homes, especially near good transit.

– I think you’re greatly underestimating the role of Gen Z (and future young folks) in the life of a community, both in the short term and the longer term in which (at least according to the research I’ve seen) a large share of current 20-somethings are likely to put down roots.

Paul T CONTE

@Michael Andersen

“(… according to the research I’ve seen) a large share of current 20-somethings are likely to put down roots.”

You left out the next piece if the research … and younger individuals preference is for a single-family home when they begin to have a family.

Paul T CONTE

Humor … Peter Courtney, Oregon Senate President, who introduced SB 10 lives in a single-family, detached house (no ADU) with a 2-car garage on a half-acre lot on the Willamette River in Salem. He’s about 1/2 mile from Salem Parkway, Commercial Street and Liberty Street. I wonder if he’ll be seeing some neighbor build a looming, river-view condo next door. Probably doesn’t have a clue what his bill would allow in his own back yard.

Or maybe Peter would be willing to help solve Salem’s housing crisis by adding 20+ units to his own half-acre lot.

Maybe Sightline should ask him?

Paul T CONTE

@Michael Anderson

Calling you out in your utter disregard for the impact of these radical upzoning gifts to developers. Please watch and justify your ignoring what Portland Planning Commissioner, Andre Baugh says would be on communities of color:

https://streamable.com/ecwz3

Michael Andersen

Commissioner Baugh’s concerns are valid. The phenomenon he seems most concerned about, though, the pushing of redevelopment into lower-wealth neighborhoods, isn’t the result of the fourplex legalization. It’s the result of the new cap on building size that Portland has also bundled into its reform in an effort to address the concerns of people like yourself who object to physical changes to higher-wealth areas.

I’ve spent the past two weeks discussing this subject with anti-displacement pros across Portland. They are in near universal agreement that fourplex legalization is a step in the right direction. They also add, accurately IMO, that zoning reform alone would be a terribly inadequate proposal for housing everyone. Many additional policies are needed.