A quarter-century ago, Washington passed a law requiring cities to allow mother-in-law suites in houses. So why are Washington legislators proposing a new bill this year to reform the rules for granny flats statewide?

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs), as these unassuming homes are known to policy wonks, may be legal under state law, but that hasn’t stopped cities from piling on restrictions and fees that can make it unworkable for homeowners to actually build them.

In recent years, a handful of cities dropped prohibitive rules and saw ADU homes take off. The trouble is, dysfunctional local politics usually makes it much easier for cities to put such rules in place than to undo them later.

The urgency of Washington’s housing shortage is worsening, pushing prices and rent higher. This statewide housing crisis warrants statewide action to ensure that all cities share the responsibility for creating more housing options. The state legislature is currently considering an ADU reform bill that would do just that (HB 1797 and SB 5812). The bill would establish a baseline set of flexible rules to remove known barriers to ADU construction and level the playing field among all Washington cities.

To demonstrate why state-level action is the right prescription at the right time, here’s a rundown of:

- the gamut of restrictions imposed by Washington cities;

- cities where liberalization unleashed pent up demand for ADUs; and

- cities that endured arduous processes to enact reforms.

Washington cities bog down ADUs with a raft of restrictive rules:

Requiring extra off-street parking for ADUs: Seattle, Bellevue, Kent, Federal Way, Everett, Kirkland, Bellingham, Yakima, Richland, Bremerton, Pasco, Shoreline, Aberdeen, Auburn, Lake Stevens, Snohomish, Stanwood, Kelso, and Tukwila

Requiring the owner to live on site in the house or ADU: Seattle, Spokane, Bellevue, Kent, Spokane Valley, Renton, Bothell, Everett, Federal Way, Kirkland, Bellingham, Pasco, Marysville, Burien, Edmonds,Shoreline, Richland, Bremerton, Tukwila, Snohomish, Stanwood, and Aberdeen

Charging high impact fees for ADUs: Everett (up to $9,130 for 2-bedroom ADUs), Federal Way ($7,580), Renton (up to $6,700)

Prohibiting more than one ADU per lot: All Washington cities (Seattle has proposed legislation to allow two)

Prohibiting backyard cottages: Bellevue, Covington, Edmonds, Medina, and Pasco

Only allowing ADUs on lots larger than 4,000 square feet: Spokane (5,000), Yakima (7,000), Federal Way (5,000), Marysville (7,200), Cheney (5,000), Vancouver (5,000), Bellingham (5,000 for backyard cottages), Kennewick (10,000 for backyard cottages)

Limiting maximum ADU size to 800 square feet or less: Spokane, Vancouver, Bellevue, Kent, Everett, Federal Way, Renton, Yakima, Bellingham, Richland, Olympia, Aberdeen, Kelso, Lake Stevens, and Snohomish

Limiting ADU height to 20 feet or less, precluding two-story cottages: Spokane, Bellingham, Richland, Tacoma, and Tukwila (unless over a garage)

Requiring the ADU to match or complement the exterior design of the main home: Spokane, Tacoma, Vancouver, Everett, Yakima, Bellingham, Richland, Bremerton, and Tukwila

But some cities have bucked the trends and gotten rid of some of the restrictions and fees that thwart people from creating ADUs:

Not requiring off-street parking for ADUs: Ellensburg, Olympia, Tacoma, and Vancouver

Not requiring the owner to live on site: Vancouver, Tacoma, Olympia, Yakima, Lake Stevens, and Kelso

Not charging impact fees for ADUs: Bellevue, Bremerton, Covington, Edmonds, Granite Falls, Issaquah, Kirkland, Lynnwood, Marysville, Mercer Island, Redmond, Sammamish, Seattle, Spokane Valley, Tacoma, Vancouver, and Yakima

Washington cities that relaxed ADU restrictions saw permits jump:

- Bellingham received a record 48 ADU permit applications in 2018 after re-legalizing backyard cottages and reducing off-street parking quotas and impact fees. Previously, the most in a single year was 12.

- Vancouver removed its owner occupancy requirement in 2017 and annual ADU permit applications rose from one in 2016, to 10 in 2017, to 45 in 2018.

- Renton reduced ADU permitting and impact fees by half in 2017 and ADU permit applications rose from two in 2016, to three in 2017, to five in 2018.

- Olympia removed owner occupancy and parking requirements and raised height to 24 feet in late 2018. The city received five applications in 2017 and four in 2018 but already received 3 applications by February this year.

Cities outside Washington have also seen ADU permits surge after loosening ADU rules:

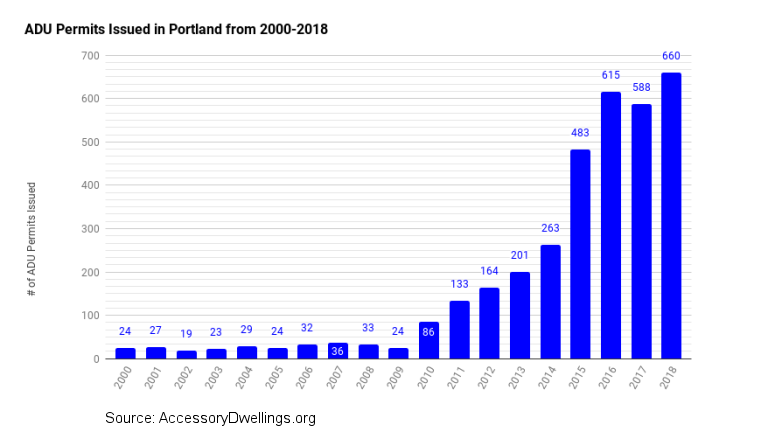

- Portland, Oregon, reformed multiple regulations starting in 2010 with a waiver of an $11,000 impact fee followed by relaxations of setbacks and design standards. As shown in the chart below, the results were dramatic: before 2010 ADU permits hovered around 20 to 30 per year, and by 2016 had surpassed 600.

- Bend, Oregon, reduced application fees and relaxed regulations in 2016 and saw ADU applications increase from 17 applications in 2015 to a high of 117 applications in 2018.

- Vancouver, BC, demonstrates the long-term potential of getting the rules right: one in three houses in Vancouver has an ADU, compared to less than 2 percent in Seattle. The main reason is Vancouver eliminated its ADU barriers starting in the 1990s, and has a set of rules very similar to the reforms originally proposed for HB 1797.

California’s statewide ADU reform unleashed ADUs in several cities:

California’s statewide ADU reform unleashed ADUs in several cities:

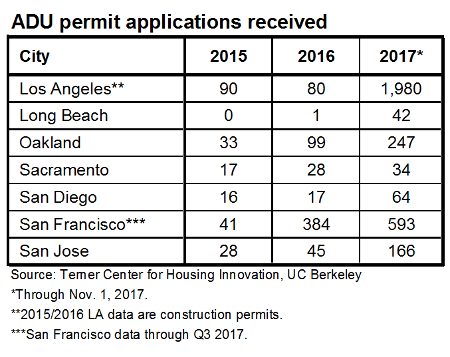

California’s statewide ADU reform (SB 1069) went into effect at the start of 2017. The law requires cities to use a ministerial—rather than discretionary—approval process, limits parking quotas, eliminates some utility connection fees, and loosens design standards. As shown in the table below, data from 2017 show a surge in ADU permit applications in cities throughout the state.

Local ADU reform can be time consuming, expensive, and capricious:

Local ADU reform can be time consuming, expensive, and capricious:

Local jurisdictions face resource constraints and political challenges to enacting ADU reform. Small cities in particular may lack the staff resources to conduct an extensive planning process with public engagement. Meanwhile, residents concerned about change often reflexively oppose any rule change that allows more homes, spooking politicians and making the city’s task that much more costly and time consuming. A state law that establishes the same baseline ADU rules for everyone takes political pressure off local electeds, and can also lighten the planning load.

Seattle’s ADU reform process is at three years and counting! The city’s effort started in late 2015, and will likely stretch to mid-2019. A large part of that delay was caused by legal appeals filed under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). The success opponents had using SEPA to delay legislation in Seattle may encourage residents of other cities to do the same, potentially gumming up ADU reform throughout the state. Washington’s proposed ADU reform bill may include a provision that would exempt cities from SEPA appeals on actions taken to meet the requirements of the law.

Other cities have also endured lengthy processes to enact ADU reform:

- Bellingham: 30-month process. The city held an initial work session on ADUs in November 2015, started working on legislation in September 2017, and passed it in May 2018.

- Vancouver: 20-month process. In December 2015 a city task force recommended relaxing ADU rules, and the city passed legislation in August 2017.

- Olympia: part of 22-month process. In early 2017 the city launched an ADU liberalization process as part of its Missing Middle housing plan, which passed in November 2018.

- Tukwila: 16-month process. The city held its first work session on ADUs in March 2017, the planning commission made recommendations in October 2017, and the city adopted reform in July 2018.

- Tacoma: 15-month process. The city began developing recommendations to loosen ADU regulations in December 2017, and will consider a final proposal in March 2019.

Tom Lane

ADUs present a way to solve the affordable housing crisis without causing visual blight for those of us who dislike tall towers. Another solution is to expand outside the urban growth boundary with 1 acre lots. Deschutes county (Bend, Oregon) is doing this in order to clear brush that could burn and destroy Bend (I assume that most trees stay in place).

Roberta Lewandowski

ADUs are a great way to conserve some of the original look of historic houses and neighborhoods, with units above the garage, in the basement, or in cottages. So much preferable to the huge, square mansions that are removing historic houses with character. And, For most of us who have seen our neighborhoods empty out when the young people leave, this is a welcome addition of liveliness.

Real Estate Podcast

One thing I’ve noticed is always that there are plenty of common myths regarding the banks intentions while talking about home foreclosure. One fairy tale in particular is the fact the bank prefers to have your house. The financial institution wants your dollars, not your home. They want the bucks they lent you having interest. Staying away from the bank is only going to draw the foreclosed conclusion. Thanks for your write-up.

https://hibandigital.com/

Brian Drake

Missed from this article are the COUNTY jurisdictions. For example, Thurston county does not allow ADUs at all – it doesn’t matter how much land you have. I contacted the planning department and their response was “we are looking at it”. They have been looking for years but there has been no action.

Landlord

Is there a way to legalize a 13 year old ADU in Sammamish? I’m unable to find any info on this, including on the city’s website and, needless to say, I’m loath to contact the city directly. Any info on what might be involved? I do have pictures of construction.

Larame Sweet

How can I get my in law quarters permitted in Pasco, my father in law had been given 24hr to vacate. He’s lived there 6 years and before we bought it someone lived there 13 years. Is it possible to get done