A backyard cottage—a garage beautifully converted into a two-story, two-bedroom 800 square foot home—allowed Becky to afford to live close to work and within walking distance of her daughter’s elementary school. It also meant she could help her aging parents stay in their home, on the same lot.

Kay built a small home behind her house so that her disabled brother could live close by and get the help he needed while keeping his independence. Kay joked that her neighbors were worried when she added an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) because it was unfamiliar in her community. But when the tiny home was completed, neighbors told her they wanted one of their own—or knew someone who’d love to rent it.

Kay is a mom and fifth-grade teacher, raising her family in a home she owns on a quiet Seattle street. In her backyard she’s built a small cottage for her brother Doug, who is not able to live independently. Photo by Seattle Neighbors, available under our free use policy.

These housing solutions are frequently thought of as isolated or rare occurrences, but that would be a mistake. It’s also a mistake that’s made, over and over again.

Americans in particular, it turns out, are not good at planning for a time when they might have a harder time getting around. They have what gerontologists and other social scientists casually refer to as “Peter Pan Syndrome”: They don’t plan their streets for people who use mobility devices to help navigate the urban terrain. They don’t plan their transportation systems for a time when they may no longer be able to drive. And, they don’t plan their homes in ways that will allow them to age in community. But mobility and self-reliance shift over lifetimes. No one is exempt from the aging process, and there will (hopefully) come a time when Americans all might be grateful for housing that allows them to age in their communities.

AARP’s recent report, Making Room: Housing for a Changing America, written in partnership with the National Building Museum, points out that this is not an individual problem, one that each of us can or should solve on our own. The lack of housing to meet our changing demographics and budgets is quickly becoming one of the defining problems in American cities:

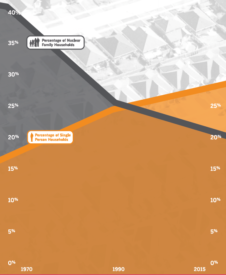

Nuclear family households overtaken by single person households. Graphic courtesy of Making Room: Housing for a Changing America, National Building Museum, used with permission.

“America’s current housing stock doesn’t fit a rapidly aging population. In 2017, more than 19 million older adults were living in housing that didn’t provide them with the best opportunity to live independently, and only about one percent of the nation’s present housing is equipped to meet their needs.”

In fact, single-person households now outnumber “traditional” nuclear family households: Single-person households account for 28 percent, while nuclear family households account for only 20 percent. This isn’t a bad thing in itself. What’s bad is that American housing stock hasn’t been keeping up. Our cities are overwhelmingly zoned to produce stand-alone single homes designed for nuclear families. Most neighborhoods in Cascadia and beyond don’t allow a range of home options that would work better for adults living alone, young couples starting out, older adults who want to downsize, single parents and their children, or adults living together in shared housing.

AARP’s main policy prescription to improve our cities, and better align housing options with Americans’ changing needs? Expand the menu of housing options, and grow their supply. People need more homes, of all shapes and sizes, and they need community intervention to stop preventing them from being built.

Making Room spells out the main barriers that American cities can clear away in order to address the root causes of these housing affordability and accessibility challenges:

- Evolve local zoning codes. Don’t continue to ban creative, flexible housing solutions, or place so many onerous requirements on projects that make them infeasible,

- Re-legalize the kinds of compact, walkable neighborhoods that can support transit, or neighborhood businesses by allowing “missing middle” housing types—like duplexes, triplexes, and quads—in more places, and

- By doing both of those things, increase our ability to close the gap between American households’ income and the amount they need to spend on a place to live.

The report also gives concrete examples of age-friendly housing types that American cities could re-legalize– exactly the kinds of homes Americans would be wise to imagine themselves living in someday or imagining a child or friend needing at different stages of their lives. For example:

Smaller, less expensive homes that require less upkeep let nonprofits serve more households

The John and Jill Ker Conway Residence in Washington, D.C., accommodates a variety of different people at different stages of life and incomes by providing small 500- and 400-square-foot apartments, 340-square-foot dormitory-style two-bedroom suites, and 250-square-foot single-room occupancy housing. Spearheaded by the nonprofit Community Solutions, the building includes 60 homes set aside for formerly homeless veterans, 47 for households making no more than 60 percent of the area’s median income (AMI), and 17 for tenants making no more than 30 percent of AMI. The project is among the first of its kind to have full-time case managers from Veterans Affairs on-site.

John and Jill Ker Conway Residence. Photo courtesy of DLR Group and National Building Museum, used with permission.

Creative, flexible shared housing options promote community and social networks

Denver’s Aria Cohousing Community arose when the Sisters of St. Francis sold Maycrest Convent and 17.5 acres surrounding it to local developer Urban Ventures. Urban Ventures reconfigured the building and site for a multi-generational cohousing community, part of a larger urban infill project called Aria Denver. The four-story building now holds 28 condos with between one to three bedrooms, two of which are also physically accessible. All homes share a large communal kitchen, dining area, and community room, as well as a library, guest suite, and gardens, among other amenities. Eight of the community’s 28 condos are regulated affordable, and sold for less than 80 percent of the area’s median income.

Aria Cohousing Community. Photo courtesy of Urban Ventures LLC and National Building Museum, used with permission.

What’s needed is a lot more flexible ways to adapt existing housing stock—namely, ADUs

Moray Eco Cottage was converted from a formerly detached garage, in a backyard in Portland, Oregon. The garage underwent a radical transformation and expansion, while adhering to strict Historic District design rules. The 508-square-foot Eco Cottage was built using sustainable building practices to reduce energy consumption. The ADU currently serves as a guesthouse and short-term rental. Long term, the homeowner plans to downsize and occupy the space herself.

Moray Eco Cottage kitchen. Photo courtesy of Jack Barnes, PC and National Building Museum, used with permission.

It isn’t enough to just re-legalize ADUs. What also needs changed are local zoning rules that, especially when combined, can make them too expensive or difficult to build. Take Bellingham, Washington, for example. In 2018 the city legalized backyard cottages and reduced off-street parking requirements and impact fees. Within six months, the city saw more than three times as many ADU permit applications as in previous years. Portland, Oregon, recently became one of the nation’s most supportive municipalities for Accessory Dwelling Units only after it made key changes to its zoning code. From AARP’s report:

“The city repeatedly relaxed or removed restrictions and incentivized construction by wltiving the infrastructure impact fees that were especially onerous on the homeowners seeking ADU permits. Between 2010 and 2016, Portland issued just short of 2,000 ADU building permits, a steep rise over the previous decade. Two interventions — easing design and setback standards (2015) and allowing ADUs to be used for short-term rentals (2014) — coincided with a surge in issued permits. In 2016, in excess of 600 permits were issued, more than double the number from 2014.”

When asked in the 2018 AARP Home and Community Preferences Survey, people age 50 or over who would consider building an ADU responded that they’d do so in order to: provide a place for a loved one to stay who needs care (84 percent), and provide a home for family members or friends (83 percent). Other reasons included wanting the security of having another person living close by and earning extra income from rent.

ADUs will likely prove a critical part of the solution to America’s housing affordability crisis. Because cities largely ruled out all but single-dwelling homes for so long, ADUs are one way to modify these existing homes to fit real American households. In short, ADUs will help ensure that our communities have the kinds of home choices and flexibility that will serve their residents long into the future.

The full report is available at AARP.org/makingroom

Paul T CONTE

Where are you getting the following “fact”?

“In fact, single-person households now outnumber “traditional” nuclear family households: Single-person households account for 28 percent, while nuclear family households account for only 20 percent.”

The 2017 ACS 1-year estimates for Oregon (Table S2502) does show 27.7 percent of occupied housing units are “Householder living alone.” But “Family households” is 63% and “With related children of householder under 18 years” is 28%. And, of course, that means that 72.3% of occupied households are not “single-person” households.

This is the kind of bogus slanting of facts that destroys the credibility of Sightline bloggers.

Yes, allowing true, small (even “tiny”) Accessory Dwellings for relatives, wards, dear friends and others is a terrific idea and is based on either owner occupancy or renting to a closely-affiliated cohort (e.g., a parent and the family of a child of the parent).

On the other hand, using “ADUs” as a Trojan Horse for mere increases in density is dishonest and should not be used as a way to “bust” single-family neighborhoods.

And the argument for true “accessory” dwellings doesn’t need slanted representation of the facts to make the case.

Octavius Vanzandt

Paul,

I’d think the answer is pretty obvious. A traditional nuclear family means 2 parents with 1 or more children. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_family

So, your stats are based on an ignorant understanding of the terminology.

I hope this helps your understanding of the world.