Press, pundits, and elected officials—Left and Right—drum a message into our heads: “Americans hate taxes.” Look! I’ve just done it again! (Note to self: Refuting and repeating a negative frame simply serves to reinforce the frame.)

But Vanessa Williamson, fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution and author of the book Read My Lips: Why Americans Are Proud to Pay Taxes, says that the notion that Americans hate taxes “has become a truism without the benefit of being true.”

Williamson’s research digs into a pervasive but largely buried alternative to the conventional wisdom:

Pollsters have been asking Americans whether “it is every American’s civic duty to pay their fair share of taxes.” Every year, about nine in 10 Americans agree with that sentiment. In 2009, 3 percent of respondents disagreed. That level of accord is very rare. To give you a point of reference: About 6 percent of Americans think the Apollo 11 moon landing was faked. On the civic responsibility of taxpaying, Americans are about as close to consensus as they ever get.

So how do Americans feel? Williamson says that “paying your fair share of taxes is a norm that a vast majority of Americans hold dear.” When you ask Americans about taxes (and she has been asking—for nearly a decade), their thoughts are anything but small. “They talk about what their country means to them,” she says, “and about the world they hope to leave for their children and grandchildren.” For better and for worse, people connect taxes to their core values and sense of community identity—and of right and wrong.

Especially around “tax season,” most Americans participate in customary griping and complaining, but Williamson finds that Americans view paying taxes as something to be proud of. “It is evidence that one is a responsible, contributing, and upstanding member of society,” she writes, “a person worthy of respect in the community and representation in the government.”

This is a double-edged sword. Broadly held patriotic pride in paying taxes signals promise for more productive conversations about government investments, revenue, and reform. But, as Williamson tells us, a belief among many Americans that they themselves pay taxes, but that many others, especially the very rich and the poor, do not pay their share is deeply corrosive to the social fabric. “The widespread misperception that immigrants, the poor, and working-class families pay little or no taxes,” she writes, “substantially reduces public support for progressive spending programs and undercuts the political standing of low-income people.”

What’s set up is a dangerous litmus test for civic “worthiness” or “who counts as American,” and it is exacerbated by racial and national prejudice.

But it’s unfounded. Lower income Americans as well as undocumented immigrants pay a substantial part of their income in sales taxes, payroll taxes, and fees. But a mainstream—and sometimes politically strategic—preoccupation with income taxes renders these other contributions nearly invisible. The point is, income taxes aren’t the only way people uphold their sacred civic duty.

When pollsters ask what bothers people most about taxes, “Americans overwhelmingly say the feeling that the wealthy and corporations are not paying their fair share.” Corporate loopholes and overseas tax havens are viewed by Americans as very unpatriotic. Even when corporate tax avoidance is legal, Williamson says, most Americans believe corporations should be punished for taking advantage of the system. This goes back a while. She points out that the original Boston Tea Party is wrongly remembered as “founding example” of anti-tax fervor. It was not motivated by high taxes, but rather it was “an act of resistance against what we might deride today as a corporate tax loophole.” A 2017 IRS survey found that “The majority of Americans (88%) say it is not at all acceptable to cheat on taxes; this ethical attitude is not changing over time.” Corporate tax avoidance—even when carried out legally—inflicts damage not only as lost revenue, but by eroding Americans’ trust in government. Here again is an opening for discussions of taxes as patriotic and an argument for more corporate accountability as paramount to a healthy, responsive democracy.

So, what do we make of this? We have work to do to overpower the default thinking established by decades—even centuries—of relentless anti-tax rhetoric. The good news is that Americans are fundamentally more favorable about taxes than that rhetoric insists. In fact, for more than 30 years, Williamson shows, Americans have remained committed to the principle of taxpaying and they have grown markedly more receptive to tax increases in recent years. The data are surprising: “Voters today are as likely as not to approve a state tax increase.”

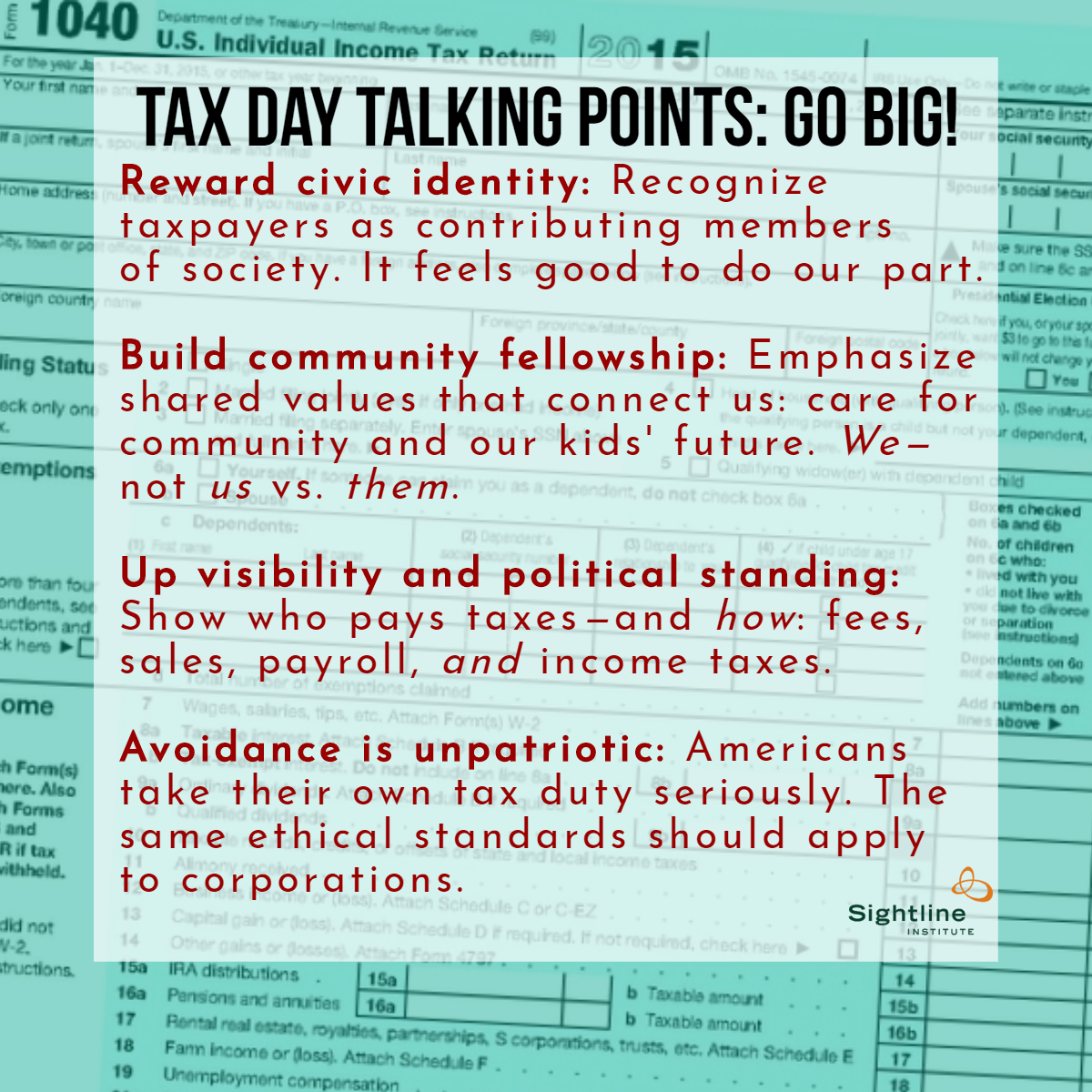

Of course, polling and Williamson’s interviews revealed what many Americans feel in their gut; when the government fails to live up to its democratic ideal, any pride people might feel in taxpaying is subverted. In that context, better messages about taxes aren’t an adequate fix. Still, we can make good progress on many policy fronts by building on the sturdy foundations for positive tax attitudes that Williamson has uncovered, especially because those foundations are so often invisible and buried. Here are some ways to start:

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

I recommend this Planet Money podcast for more surprising American tax tidbits like:

- Tax Day is a uniquely American phenomenon. In most other countries around the world the day federal taxes are due is not a national event, in part because there’s no culture of anti-tax fanfare and, more important, because in most places filling out the forms and paying is far simpler.

- But anti-tax operatives like Grover Norquist prefer to keep tax filing cumbersome and frustrating. The logic is that “if paying taxes is difficult, people will hate taxes and vote against them.”

- Simplifying the process for filing tax returns is opposed not only by anti-tax political operatives, but also by the tax preparation industry lobby. Right now the US Congress is considering a measure that would permanently bar the Internal Revenue Service from offering a simple, free tax preparation service online—competition for products such as TurboTax. It already passed the House.

- Also: A US House bill to abolish the IRS currently has 29 Republican co-sponsors.

Jeffery J. Smith

Paying one’s fair share and paying taxes have some overlap, not a lot. Humans conform, naturally. When Lynch mobs were commonplace, the whole town turned out. Same for burning witches. Morality is not a popularity contest. And letting people who don’t work but opine while occupying public office, who live off others paying taxes, set them or target them, that’s madness. They don’t get to do that, not in a just world–too much obvious conflict of interest. Finally, taxists ignore their responsibility for endless war, bridges to know where, corporate welfare, sprawl, etc, and all their wasteful, harmful consequences. Give me those Quakers with guts any day.