If you want to understand the new housing crisis that’s looming over the Pacific Northwest like a big silver wave about to break, consider three numbers from Oregon.

616.

3,810.

And 6,781.

The first is the approximate number of wheelchair-ready homes the state needed to add to its housing stock in 2011 to keep up with the increase of age-related ambulatory disabilities that year.

The second, six times larger, is the approximate number of wheelchair-accessible homes the state needs to add this year.

The third is the number the state needs to add two years from now and every subsequent year into the foreseeable future. It comes to about one fifth of new homes.

The precise future is unknowable, of course. But that’s exactly why the housing market is unlikely to naturally prepare itself for this. Over the next 10 years, hundreds of thousands of Cascadian seniors are going to lose the ability to walk easily—and they don’t know it yet.

It’s a daunting problem. If it goes unsolved, it will put even more pressure on the tiny minority of homes that are already universally accessible. A US study from 2011 put that figure at just 200,000 units nationwide, with 8,400 of them in the Portland metro area. A scramble for those homes over the next decade could leave thousands of people of all ages without good housing options for living with their disabilities.

But here’s a bit of good news you may not have heard: There’s a rising movement in the Northwest that would make it far easier—and in some cases, mandatory—to add accessible housing to every neighborhood and jurisdiction.

It’s the movement to re-legalize “middle housing” options like duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and accessory dwellings.

If Oregon passes a law legalizing those options in all larger cities and the Portland metro area, it could boost Oregon’s housing production by a thousand accessible homes per year or more—without a dollar of subsidy or a drop of further regulatory ink.

And due to a little-known federal law, that boost could be particularly strong if cities can learn to embrace one type of structure in particular: the fourplex.

We can’t make accessibility abundant until we’ve made stairs optional

Lenore Prato on the patio outside the daylight basement she would convert to a wheelchair-ready home if it were legal. Photo by Michael Andersen, used with permission.

Lenore Prato walked across the smooth concrete floor of her basement with her hands flipped outward to the width of a wheelchair or walker, navigating invisible corners in the aging-ready home she’s imagined but isn’t allowed to create.

“This is the kitchen,” she said, pacing the large unfinished room. “This is an island. This is where the stove and storage would be.”

For the moment, the mostly empty room is where Prato’s two teenage daughters watch television and where her 84-year-old father, who lives with her 83-year-old mother in the converted garage behind the house, works out on his stationary bicycle.

But as Prato walks out of the basement onto its patio and up a ramp to the sidewalk, she sees a home for one or both her parents if someday they can’t climb the steps to their little house. Or maybe the basement would someday be home for her and her husband, Ken.

“My husband’s family is Korean; my family is Italian,” she said. “We both grew up with grandparents living with us. That’s what you did! We’re trying to do it here.”

For tens of thousands of Cascadians trying to do the same thing—to live comfortably, now or in the future, despite trouble walking—one of the biggest obstacles is all too familiar.

It’s the stair.

Simply put: Where land prices are high, it’s hard to profitably build a one-story building. So almost all new buildings in growing cities have at least two stories. And when only one home is allowed per structure, that means fully accessible homes are essentially illegal. There’s always going to be an upstairs that some people can’t easily reach.

This is where “single-family” zoning laws collide with the increasingly urgent need to build a lot more one-level homes.

The obvious answer is to do exactly what Prato hopes to: Stack two or more homes on top of each other and turn the ground floor into a complete, fully accessible unit. That’s why it’s encouraging that the states of Oregon and California and cities like Bend, Milwaukie, Olympia, Portland, Seattle, Tacoma, Tigard and Vancouver have been working on plans to make this legal in more cases.

But the laws under consideration in Oregon, California and Portland would go even further. They’d make accessibility for some units mandatory.

But doing this wouldn’t require a mandate of their own. It’d simply mean producing a lot of one particular building type.

Part of the magic of four units: An obscure federal mandate

An old Victorian house in Portland being internally divided into a fourplex. By federal law, its ground-floor unit had to be universally accessible. Projects like it are currently legal only on a tiny share of Portland’s residential land. Photo by Michael Andersen, used with permission.

The seven words of federal law that could create thousands of new accessible homes if fourplexes are legalized across Cascadia have sat, buried and mostly forgotten for years, in the “definitions” section of the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988.

The words are “buildings consisting of 4 or more units.”

Under the Fair Housing Act, the fourth home within any structure triggers a requirement that every new ground-floor home, and every home in buildings with elevators, be wheelchair-accessible. Among other things, that means “an accessible route into and through the dwelling” and “usable kitchens and bathrooms such that an individual in a wheelchair can maneuver about the space.”

Those provisions add expense, no question. A bathroom large enough to maneuver a wheelchair requires floor space that can’t be a bedroom closet or another kitchen counter. But that’s exactly why the market currently has so many fewer of these homes than it’s about to need.

Not everyone needs a wheelchair-ready home, and many homes are accessible to people with some disabilities even without fully meeting federal standards. So states and cities shouldn’t require every new building to have accessible units. But if fourplexes were to replace McMansions as the standard building that goes up in the low-density zones of a growing city, the existing mandate in the Fair Housing Act would gracefully create a healthy flow of new wheelchair-accessible homes in low-density areas that, for the most part, currently lack any.

That’d be especially important in the many cities where almost all new housing has three stories or less, because incomes and rents are generally too low to pay for the sort of larger buildings that include elevators.

“We consistently have surveys showing how people consistently want to stay in their own homes and community,” said Bandana Shrestha, engagement director for AARP Oregon. Shrestha’s organization, which advocates for people over 50 and their families, is an enthusiastic backer of the fourplex legalizations under consideration in Oregon and Portland.

Last year, a city-funded study of Portland’s fourplex legalization projected that it’d create about 500 new “missing middle” buildings across the city each year, the vast majority of them fourplexes. That’s probably optimistic—a different study assumed triplexes would be most common. But further tweaking the plan to encourage fourplexes, for example by allowing a little more building size to allow that extra bathroom and kitchen space, would maximize the share of new buildings that wind up as fourplexes.

History’s biggest wave of 75-year-olds starts to arrive in two years

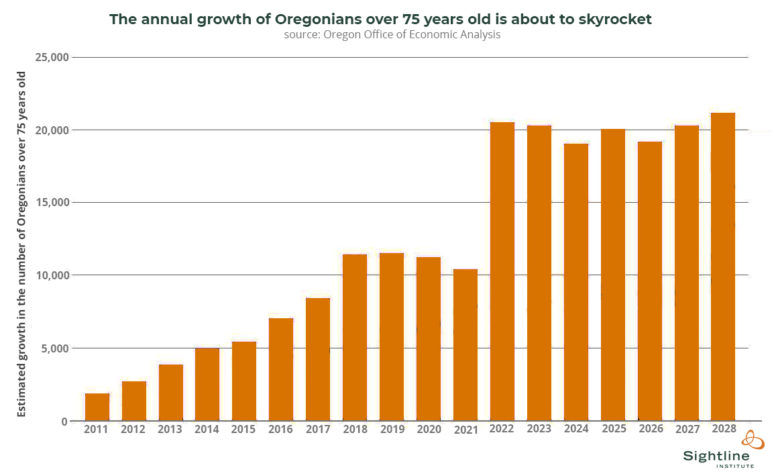

Original Sightline Institute graphic by Kelsey Hamlin, available under our free use policy.

Alan DeLaTorre, director of Portland State University’s Age Friendly Cities project, is a middle-aged professor with a poetic phrase for something he thinks his society needs urgently: to “wake up to our own future selves.”

“About the age of 75, we start to see a really strong correlation between age and disability,” DeLaTorre said.

According to the US Census, 16 percent of Americans aged 65 to 74 have an “ambulatory disability” that limits their walking. For age 75 and above, the ratio is 33 percent—a risk that starts lower but rises steadily every year. Both ratios are essentially the same in Oregon and in Washington.

Apply that 33 percent ratio to the rising over-75 population and you’ve got some idea of the shift Cascadia’s housing market needs.

So although the first Boomers’ 75th birthday won’t itself lead to a sudden surge in people looking for accessible housing, the number of people with ambulatory disability is about to grow rapidly, and maybe indefinitely.

DeLaTorre argues that’ll require further shifts to zoning laws that were, in some ways, developed to serve those same Boomers’ youth.

“What we were planning for in the post-World War II is the baby boom,” DeLaTorre said. “We weren’t planning for an aging boom. Which is what eventually happened anyway.”

Thanks to the exclusionary laws passed during that baby boom, most Americans have now spent their whole lives in cities where fourplexes are unusual. So as states and cities debate zoning reform, there’s inevitably pressure to pare down fourplex proposals to allow only triplexes, or only duplexes. (That’s exactly what happened last year in Minneapolis.) Another possibility: fine print ensuring that even if fourplexes become legal, they remain rare.

But this turns out to be a particularly counterproductive compromise. When it comes to accessible housing, four is a much better number than two or three.

Fourplexes are great not only because they can create twice as many homes as duplexes in neighborhoods where more people would like to live. In the United States, every new fourplex also helps solve a whole different problem: preparing about one-third of us for a more comfortable, stable and independent old age.

Armando J Zelada

Excellent. Thanks for getting the word out about a different kind of equity, diversity, inclusivity issue of aging. -A J Zelada

Harry Weiss

A clarification:

Conversion of buildings originally constructed and occupied for any purpose (including previous housing uses) prior to March 13, 1991, are not subject to the fair housing accessibility regulations. The controlling factor is the “first use” provision – not the four unit threshold.

(See Fair Housing Accessibility First FAQ Items 17 and 22)

The Victorian house conversion pictured in this article may have opted to include the accessible ground floor unit, but that would not be required under Fair Housing, whereas a newly built fourplex of stacked units would require it.

Michael Andersen

Thanks, Harry! That’s correct, the fourplex pictured did opt to include ground-floor accessibility. I didn’t know the requirements for conversions, so this is good to know.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think any of the unit-count projections from Portland include any of the unit gains that may come from internally dividing big houses. They assume all new fourplexes will be newly built.

Carol Trekas

Why does Eastmoreland think it is better than Westmoreland? All our homes are important to be on a historic register. Hopefully the Mayor and City Council think the same thing.