Many North American cities are oddly un-city-like compared to their peers in Asia, Europe, Africa and even South America. Our cities are weirdly spread out and the damage to our environment and economy is colossal.

Why did this happen?

The New York Times‘s “1619 Project,” launched in print over the weekend, sets out to explain various distinctly American characteristics with a decoder ring: chattel slavery. Understand the ways multigenerational slavery twisted US society, it argues, and you’ll understand more about everything else in the country, too.

One of the essays, by historian Kevin Kruse, looks at how modern American transportation and housing were shaped by deliberate and largely successful attempts to preserve racial segregation. The effects, he argues, are visible on downtown freeways every weekday morning as hundreds of thousands of commuters try to drive in from far-flung suburbs.

He’s writing about Atlanta, but much of the story will be familiar to anyone sitting at the Rose Quarter in Portland or I-5 through downtown Seattle.

Commuters might assume they’re stuck there because some city planner made a mistake, but the heavy congestion actually stems from a great success. In Atlanta, as in dozens of cities across America, daily congestion is a direct consequence of a century-long effort to segregate the races. …

At first the rule was overt, as Southern cities like Baltimore and Louisville enacted laws that mandated residential racial segregation. Such laws were eventually invalidated by the Supreme Court, but later measures achieved the same effect by more subtle means.

Kruse goes on to discuss suburbanization and “white flight,” both of which were federally subsidized by freeway construction and tax-free mortgages but doesn’t spell out the factors that made suburbs so disproportionately white. What linked sprawl and segregation?

Racial wealth gap + low-density zoning = More segregation

Some of the suburban power to exclude came from racial discrimination by the federal government, the real estate industry, law enforcement, and neighbors. And some was baked into suburb-style zoning—separating homes and shops, banning apartment buildings and even duplexes—requiring everyone to pay for one or more cars and for a hefty amount of private land.

Sprawl enforces segregation, in other words, because the median white family has $171,000 in wealth and the median black family has $17,600—a gap created by slavery and perpetuated by both deliberate racism and systemic racism.

One of those systems was low-density zoning: a technically race-blind way to continue a long chain of segregation policies, from racial zoning to restrictive covenants to apartment bans.

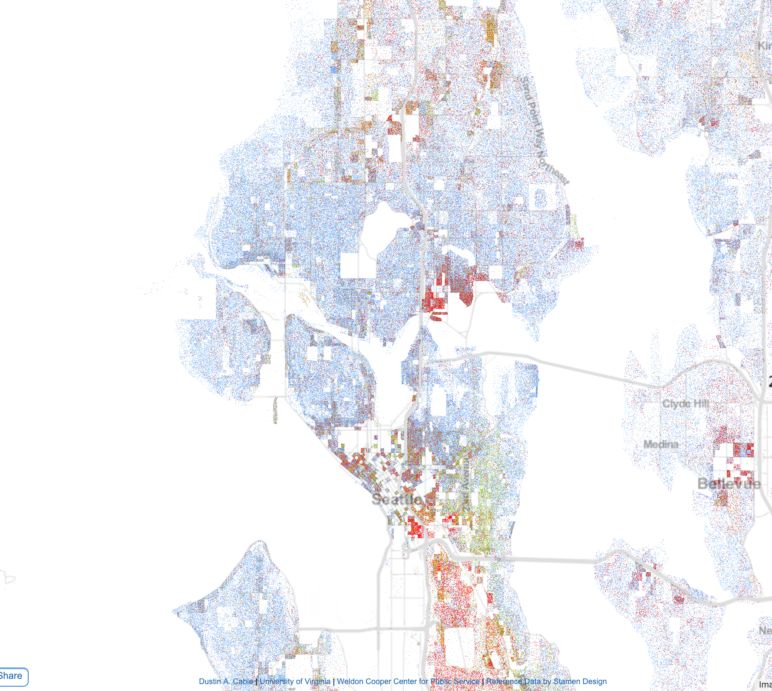

This map shows much of Seattle by population, broken down by race. Each dot represents one person. White householders are marked in blue, Asian-American householders in red, black householders in green, Hispanic or Latino householders in orange. Source: 2010 Census via University of Virginia.

Two Portland State University professors, Lisa Bates and Marisa Zapata, explained last month in an Oregonian op-ed how this plays out:

Limiting sprawl reduces income segregation—the wealthy aren’t isolated in distant enclaves, first-time homebuyers don’t have to “drive till they qualify,” which adds huge transportation costs to their budgets, and lower income families can access transit and jobs from close-in rental homes.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, where even our biggest cities were built mostly after modern zoning became popular in the 1920s, auto-oriented sprawl is common within a few miles of every downtown. That’s one reason segregation took root here, too, across the continent from Virginia’s tobacco farms.

As I wrote last year, you don’t have to be racist or classist to live in a neighborhood shaped by racism and classism. But whoever you are and wherever you live, your life is still being shaped by the ways these forces shaped your neighborhood.

Very likely, your life is being shaped by this every weekday morning.

Michael Andersen, Sightline senior researcher, writes about housing and transportation. For questions or interview requests, contact Senior Communications Manager Ed Guzman at ed@sightline.org.

Sarajane Siegfriedt

How can you write about sprawl and omit any mention of the Growth Management Act of 1990 that powerfully limits sprawl, allocates growth by agreement among municipalities and preserves agricultural land? Doesn’t fit your narrative?

Michael Andersen

The GMA is a good tool for slowing sprawl, Sarajane! As we all know, though, it’s only as good as actual land use practices at the local level. Here’s some old work on this subject from my colleague Clark, with a pretty compelling/disturbing map:

https://www.sightline.org/2012/07/18/new-report-rural-sprawl-in-metropolitan-portland/

At its best, the GMA is a way to push public and private investment in the direction of urbanization. But for it to really work in an equitable way—without becoming a tool that drives up the cost of housing, as its critics have always claimed it would—we also need to take constant action to ensure that infill is (a) legal and (b) actually happening. That’s the focus of a lot of my work here.

RuthAnn

This article is primarily referring to the suburbanization that happened earlier than the 80s or 90s.

Unfortunately, the current situation has worsened. As downtowns revitalize low-income housing locations are being purchased by developers. Since growing cities no longer have empty lots, developers are bulldozing low-income housing sites and retail space and replacing them with luxury condos and upscale restaurants and retail.

Previously, minorities were “stuck” in downtown urban settings, and now they find themselves competing for an insufficient supply of affordable housing.

Michael Andersen

I totally agree that the recent flow of money toward central cities and older buildings and neighborhoods has shaken this narrative and caused the problems you mention. But we also shouldn’t ignore the fact that suburbanization continues rapidly:

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/05/24/big-city-growth-stalls-further-as-the-suburbs-make-a-comeback/

Rep. Alissa Keny-Guyer

I love your articles! Please write one about the negative role that the current Mortgage Interest Deduction (which allows second homes and is not means tested by income) plays in exacerbating racial disparity in home ownership. My testimony for my 2019 bill in the Oregon Legislature: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/191953

Michael Andersen

Thanks very much, Rep. Keny-Guyer! Great idea. I just sent you an email.

David Fisher

Just had week long exploration of Boston. Boston a very mature City about the same size as Seattle but three times the density. A very well established Boston ‘T’ train / light rail and bus system with miles and miles of 3,4,5 story apartment buildings between the transportation links and little to no parking except on the streets. Seems Seattle needs to take a hard look at it’s miles and miles of single family zoned housing stock and let people start redeveloping into denser 10-20 units per acre apartments/ condos if they truly want to become an world class affordable interesting city with housing for all including the homeless.

John Dautovic

Segregation is just a modern word for tribalism, it’s imprinted in our genetic code. Anyone can ascribe cultural failings for any reason they wish, there’s as many reasons as there are people. Victimhood is just as old as tribalism.

Michael Andersen

I’d differ: prejudice is a modern word for tribalism, and IT’S imprinted in our genetic code to some extent. But “us”-ness … that is, the set of people we tend to be prejudiced toward and against … is shaped by our social milieu. Which is shaped by segregation. Which has been created by illiberal, unconstitutional laws.

Prejudice will always be with us, and I think it’s something we can recognize and counter in ourselves if we understand that. But segregation is one of the various means by which we pass good and bad fortune from one generation to the next.