Imagine hordes of unused, electric e-scooters stirring in the middle of the night, twitching their camera-studded handlebars side to side. Then slowly, methodically, they roll along sidewalks with their headlamps aglow. The silent scooters pause at each cross-walk and, with two twists, assess the street for signs of life. Inexorably, they make their way, mile after mile, until they reach the object of their quest and begin an unfamiliar, mechanistic ritual, guided by some unseen force. More and more scooters arrive, all arranging themselves to feast on the warm, beating heart of … an electric charging station.

It’s not a horror movie.

It’s how Cascadia’s cities could make micromobility services more useful, accessible, and economically viable. Slow-moving, empty, e-scooters piloted by remote operators would provoke smiles rather than shrieks as they expand access to convenient, low-cost mobility and reduce sidewalk clutter. With smart regulations to enable scooter drones, cities could pave the way for more shared, electric, and eventually autonomous mobility. Be unafraid! Be very unafraid!

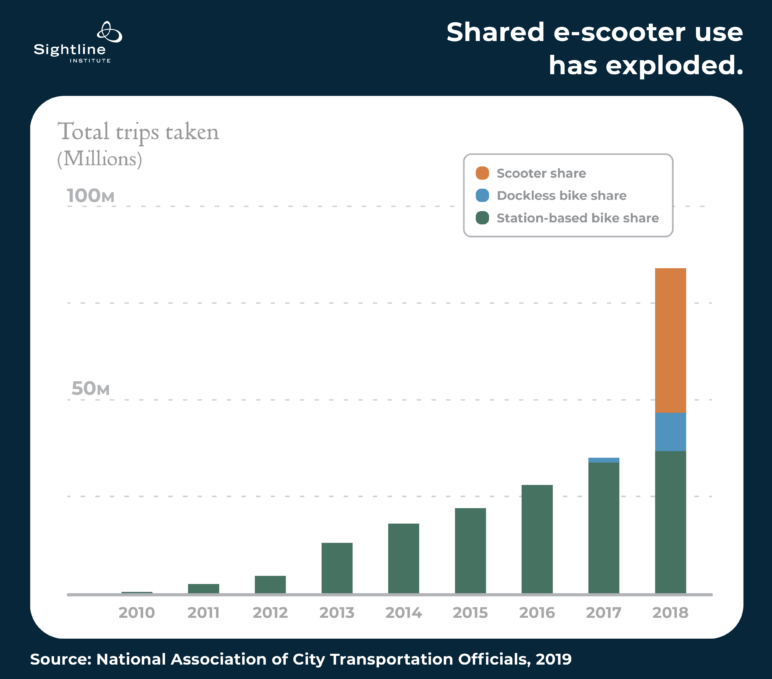

The growth in shared e-scooter use in cities across the globe in the last two years has been fantastic. According to a report from the National Association of City Transportation Officials, shared e-scooters in the United States went from zero trips in 2017 to 38.5 million trips in 2018. In their first year, e-scooter operators provided more trips than station-based bicycle programs that have been running for nearly a decade.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Over half of all the trips of all types in the Puget Sound region are under two miles, a distance well served by bikes and e-scooters. This represents an enormous market for micromobility services. But for all their popularity and potential, shared e-scooter programs have presented challenges for cities, riders, and program operators. Cities struggle with sidewalk clutter that obstructs pedestrians and people in wheelchairs. Riders can’t count on finding an e-scooter at the beginning of many trips and so only use the service opportunistically. Program operators outside of dense urban cores lose money because utilization is low and the costs of sending workers in trucks out daily to reposition and recharge scooters is high.

In October 2019, a start-up co-founded by a former Uber executive announced a new service to address these challenges. Disappointing fans of the Walking Dead, the company passed on branding itself as Zombie Scooters and instead went with Tortoise, evoking Aesop’s fable of the slow and steady terrapin who wins the race. Tortoise retrofits e-scooters with cameras, a steering motor, retractable training wheels, and a controller so that a remote operator can drive the scooter at less than 5 mph to a new location. The operators, who may be located in control centers hundreds of miles away, maneuver the scooters along safe travel routes that have steady connections to 4G cell service. Other companies like Uber and Segway Ninebot have similar technology under development. Scooters with fully integrated remote driving capabilities will enter the market in the first half of 2020.

Making E-scooters Work For Cities

The Tortoise technology solves the sidewalk clutter problem by allowing drone operators to move poorly parked e-scooters to approved parking areas that don’t obstruct pedestrians and people in wheelchairs. The technology also makes micromobility services more equitable by moving e-scooters to areas that have lower incomes and lower densities so all communities have access. Some cities already impose requirements for equitable access on operators but remote repositioning allows rebalancing to happen multiple times a day and without the need for emissions-spewing trucks.

The technology would also expand the use of Cascadian cities’ recent investments in bike lanes and transit. Users can summon an e-scooter to their location via a smartphone with accurate vehicle arrival times, which would massively expand the number of people who have ready and reliable access to transit stops. Transit riders typically travel less than half a mile to reach a stop, a distance covered in ten minutes of walking. In that time, someone on an e-scooter can travel two miles, a sixteen-fold increase in the land area accessible to any given transit stop. E-scooters could extend the feasible range on both ends of a transit trip, making buses and trains a viable option for many more users.

Consider Bellevue, Washington, a suburb of Seattle, and the hometown of Tortoise co-founder Dmitry Shevelenko. The regional transit system will open a new light rail station in 2023 in downtown Bellevue and Amazon plans to add up to 15,000 new workers in nearly 5 million square feet of new office space over the next five years. E-scooters located at the city’s transit center would allow many of those workers to ride quickly to office locations within two miles, greatly expanding the number of potential transit riders. With remote repositioning, during the morning commute, each e-scooter might ferry five people from the transit center to offices and then return the same number from offices to the transit center in the afternoon. More people on transit means less car traffic on the roads and less need to build expensive parking. For that very reason, commercial real estate interests have begun forming alliances with micromobilty providers to integrate their services into projects.

Bellevue recently lost the shared e-bike service provided by Lime because the utilization was low and revenue did not cover the costs. Lime is eager to offer e-scooter service in Bellevue but current city policy prohibits it. By launching an e-scooter pilot with remote repositioning, Bellevue could test a technology that eliminates sidewalk clutter and has the potential to expand transit utilization just as the city is about to undergo a major growth spurt.

With drone operated e-scooters, riders can summon an e-scooter to their location so trips no longer begin with a wild goose chase to find a vehicle. A hurried trip to avoid showing up late for a meeting could end with a quick hop off the e-scooter by the building door before the vehicle slowly proceeds to an approved parking location. By making e-scooter trips more convenient and dependable, remotely operated e-scooters allow riders to view the service as a reliable alternative. That reliability would increase utilization and eventually drive down costs. Increased demand and vehicle utilization would result in more choices for the types of services and vehicles available, including seated e-scooters and covered e-bikes that offer protection from the weather.

Improved Economics for Operators

Today’s business model for e-scooters operates like a taxi service if the car and driver had to stay parked at their last destination and wait for a new customer within walking distance to show up. In that scenario, many vehicles would languish for hours or days, which is exactly what happens today with dockless bikes and scooters. Researchers at MIT recently analyzed the dockless bike-sharing in Singapore and showed that if operators used remote repositioning, they could have met all of the trip demand with one-tenth of the bicycles they had on the streets.

Collecting, charging and redeploying e-bikes and e-scooters cost operators $3-10 per vehicle per day, which makes the services uneconomic in all but the highest density urban areas. Enabling remote operators to drive the e-scooters, drone-like, back to a charging center would substantially reduce the companies’ operating costs and the energy and emissions associated with today’s “juicers” who often drive older, gas-guzzling trucks and vans to pick up and drop off their scooters.

Micromobility providers have experienced explosive growth that has attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital investment. But the loss of over $100 billion in value from high-flying “unicorns,” including Uber and Lyft, in 2019 has focused investors’ attention on how micromobility companies plan to make money. Higher vehicle utilization rates and lower operating costs from remote repositioning could improve the operators’ economics, especially in suburban markets, paving the path to future growth and profitability.

Action agenda for cities

Cities need to take action for this new approach to succeed. Micromobility operators have mostly abandoned the Bird playbook of flooding a city with e-scooters without ever consulting city officials. Technology providers like Tortoise and the operating partners want to work with cities to pilot remote repositioning of e-scooters in ways that allow for learning, information sharing, and program modification informed by real-world experience. Successful integration with transit services requires collaboration and conversation with multiple stakeholders that cities know how to lead.

Cities in Washington and Idaho already have state laws that allow for remotely operated, low-speed electric delivery vehicles on sidewalks that set maximum weights, speeds and insurance requirements. Cities can build on those new laws to structure short-term pilot programs that test consumer acceptance, utilization, and integration into the urban environment. Successful pilots could inform and shape full-scale programs that meet demand. A suburb of Atlanta has already authorized a pilot program with Tortoise. Cascadia’s cities should get in the race to go slow.

Autonomous, connected, electric and shared mobility holds tremendous promise for Cascadia’s cities but it will take years before we have the regulatory framework to ensure that robots will operate safely and reliably at normal automotive speeds. In the meantime, by piloting lightweight, low-speed drone e-scooters on sidewalks, cities can embrace a new mobility option that extends the utility of investments in bike lanes and transit while maintaining safe, uncluttered pedestrian spaces.

Nothing about that is scary.