In a moment when his country seemed awash in both progress and mounting peril, Martin Luther King Jr. embraced one of the world’s oldest policy ideas.

It was January 1967. Leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were navigating new political schisms and a backlash from some working-class white voters in the 1966 midterm elections.

King, his wife, Coretta Scott King, and two employees flew to a small town on the north coast of Jamaica. They holed up for a month in a house with no telephone as he wrote his fourth and final book. In it, he arrived at a simple, far-fetched idea: giving cash to all poor people until they were no longer poor.

“I hope that both Negro and white will act in coalition to effect this change, because their combined strength will be necessary to overcome the fierce opposition we must realistically anticipate,” King wrote in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

King was right about the opposition part. Today, of course, the United States has no such system of cash payments to all poor people, let alone payments large enough to end poverty. But King may have also underestimated the idea’s appeal. The month after King’s 1968 assassination, 1,200 economists sent Congress a letter in explicit support of the plan his campaign created. The following year, President Richard Nixon introduced an unconditional minimum income as his signature domestic policy proposal.

In 2020, 50 years after Nixon cynically abandoned the idea, its tide rose again.

The past wrenching and exhilarating year began with, among other things, a string of unlikely successes for the oddball presidential campaign of basic-income promoter Andrew Yang. In June and July a group of US mayors, including Tacoma’s Victoria Woodards and Seattle’s Jenny Durkan, formed Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, a campaign built on King’s arguments; by December, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey had donated $15 million to their cause. Spain passed a conditional minimum income in June. The United Nations endorsed universal basic income in July; Portland mayoral candidate Sarah Iannarone proposed a local pilot in October. In British Columbia, a provincially funded study of basic income is due any day now. The COVID crisis brought a surge in public support for direct cash payments—itself the latest step in a steady trend toward greater public support for giving people cash.

The concept had also hit the street last summer in Cascadia’s Black Lives Matter protests, when Portland police abolition activist Mac Smiff brought it up in an unexpectedly televised sidewalk exchange with Mayor Ted Wheeler over better ways to spend public money as Wheeler stood amid a crowd awaiting its nightly dose of federally funded tear gas.

“Even if they don’t contribute to society, take care of them, right?” Smiff told Wheeler. “Because we have this idea that if people don’t contribute, then they’re not worth s***. And that’s not true—we have to take care of everyone. And we have enough.”

After 2020’s new mix of progress and peril, it can come off as fantasy to talk about a minimum income or its sibling, a universal basic income that goes to both rich and poor. But the thing is, neither King or Smiff were calling for talk. They were calling for action.

So let’s actually run some numbers.

How close are we to King’s proposal today? And assuming Smiff is right—assuming we have enough—what is the path to get it done?

This is what our social safety nets look like today

Because this is Sightline, I’m going to focus on Sightline’s home territory, Cascadia.

Since the 1930s, all the world’s richer countries have gradually built systems for fighting poverty by giving poor people things like cash, housing, food, and child care. In the United States and Canada, the programs were collectively referred to by a word from the preambles of their constitutions: welfare.

We’ve all spent much of the following 90 years arguing about welfare. But what exactly does a modern welfare system look like?

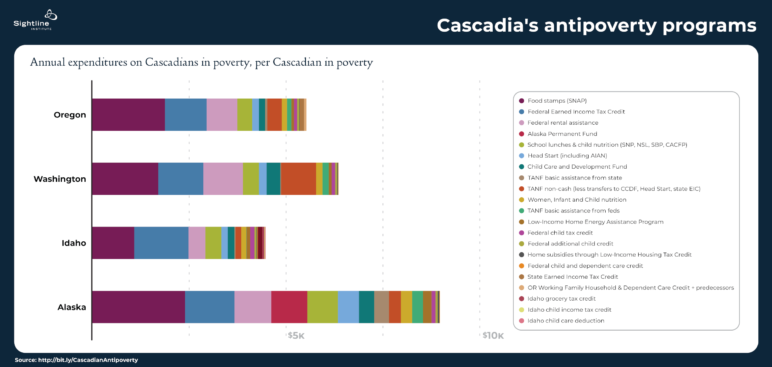

In the Pacific Northwest of the United States, it looks like this:

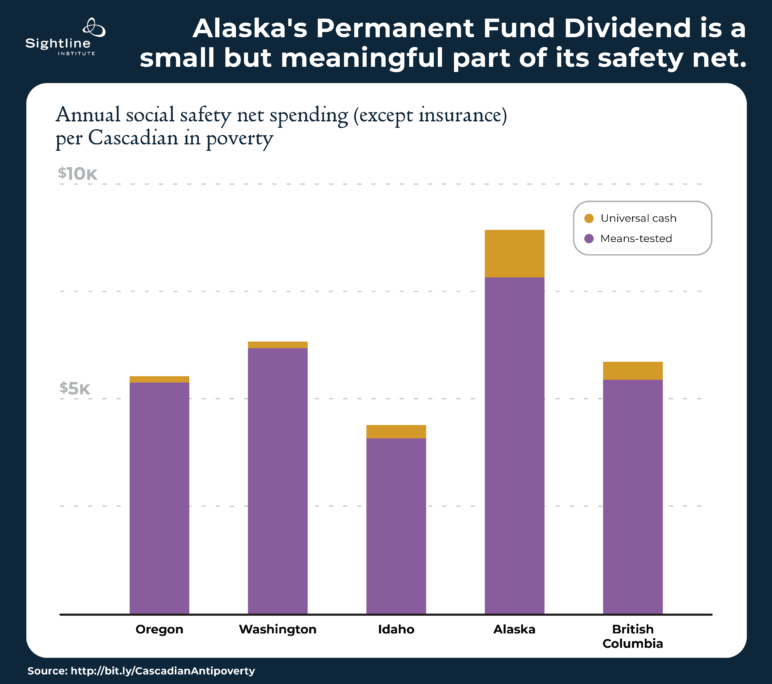

Bars represent annual state and federal spending on each universal cash program per resident of each state, plus annual state and federal spending on each means-tested welfare program per person living beneath the poverty line in each state. Does not include public services like primary education or fire suppression; social insurance like Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid or unemployment insurance; or federal administrative costs. Figures are for fiscal or tax year 2017 where available, and for 2018 in a few other cases. Data, from many sources, is here, along with an interactive version of this and other charts. Click here for a larger version.

OK, so that’s a lot of information. (And if you think it’s complicated to read that chart, imagine actually trying to use all those programs.)

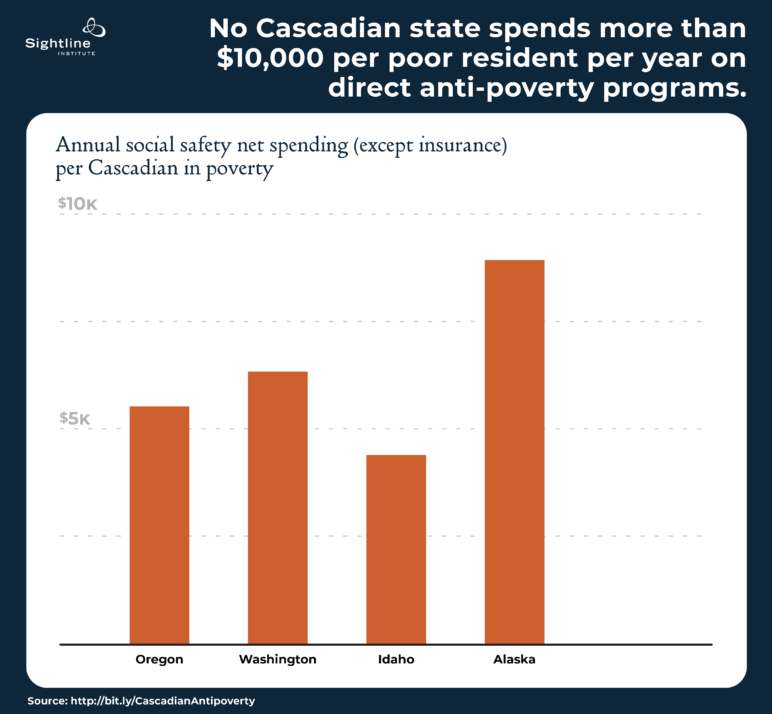

Here’s a simpler version. If you wrapped up all the Pacific Northwest’s current anti-poverty programs and turned them into an annual check to each person living in poverty, you’d get something close to this:

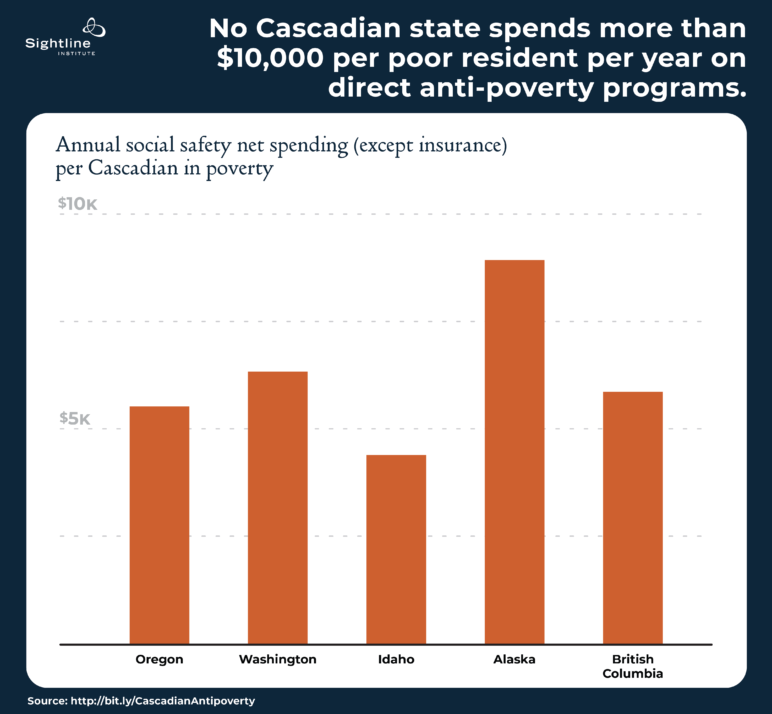

And while we’re at it, let’s bring in our Cascadian neighbors to the north, too:

Canadian dollars converted to US dollars at a rate of 1.3 to 1.

Many assumptions go into these charts. They’re my best attempt to add up the costs of all the benefits and programs that exist mostly because we don’t have a guaranteed minimum income.

For example, they don’t include huge programs like Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security or unemployment, all of which are essentially insurance programs that shift money from one part of a person’s life to another, sometimes (as with Medicaid) with various subsidies attached. These would likely be a good idea even with a minimum income. Nor do these charts include federal administrative costs. They do include tax credits, including child tax credits that function as annual cash payments to families with kids. (Unlike Social Security, payments to families with children don’t count as insurance because everyone is definitely a kid at some point.) Finally, they use a very rough measure of our safety net: total qualifying expenditures (some of which go to helping people who aren’t in poverty) divided by total number of people “in poverty,” a standard that is itself calculated differently in Canada and the United States.

Given those assumptions, these charts make a few things clear.

First, we are spending a meaningful amount of money to help the poor people among us—a good deal more, per person in poverty, than we did before Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society legislation in the mid-1960s. This is why the US poverty rate, after taxes and transfers, has fallen from 19 percent in 1967 to 13 percent in 2018. That’s one-third of poverty eliminated.

The “War on Poverty” hasn’t been won. But it might be winnable, just as King predicted it could be.

A second lesson of this chart is hidden between its lines: The government is not the only source of money or resources for poor people, and it doesn’t necessarily need to be.

The highest of these benefits, $8,930 per poor Alaskan per year, wouldn’t even cover a year’s rent for a studio apartment in Anchorage, let alone the other ingredients of a minimally decent life. But even if all these programs were liquidated and converted to cash—not necessarily a good idea, to be clear—a minimum income wouldn’t become a uniform dollar sum that every poor person receives. It’d be an average payment that is higher for the poorest of the poor and lower for the working poor.

For better or worse, most Cascadians in poverty work. In Oregon about 52 percent of poor working-age people have a job, in Washington 56 percent, in Idaho 57 percent, in Alaska 53 percent. Canada tracks things differently, but about 55 percent of all British Columbian households in the pre-tax “low income” category have at least one worker.

The point of government safety-net programs isn’t to replace work; it’s to give more people a decent life. That’s exactly what happens today, in both Canada and the United States.

This doesn’t mean that current safety-net spending is enough to meet the “indispensable” requirement laid out in King’s book, that any minimum income be high enough not to “freeze into the society poverty conditions.” But it does show how social programs currently serve people with and without income.

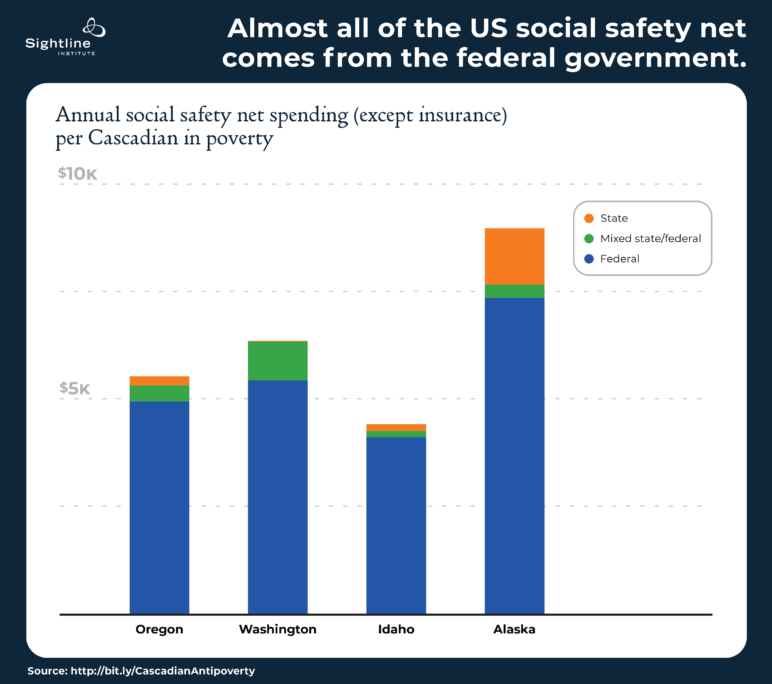

Another question: where is anti-poverty money currently coming from? Well…

As somebody who spends a lot of time thinking about state government, I took this as a reminder that everyone who’s obsessed with federal politics has a point.

Federal social-service spending dwarfs state spending. There’s a fine reason for this: states can’t print their own currency in a pinch, so they have to mostly balance their budget every year. If states were on the hook for vast social programs during fiscal and economic catastrophes like 2020’s, they could get stuck slashing aid programs in the moment that individuals and the general economy need help most.

The differences in the chart above start to explain the state-by-state differences: Idaho spends much less per person in poverty, largely because so few of its poor residents receive food stamps or housing choice vouchers, two of the largest federal anti-poverty programs. And though Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend, an annual cash payment to Alaskans regardless of income, is only part of the reason that state stands out, it’s a pretty big part.

Here’s another question that gets to the difference between minimum income (cash payments to poor people) and basic income (cash payments to everyone). Of the money that’s helping poor folks, how much of it is from programs that also go toward sending cash to everybody else?

Across Cascadia, almost all of the safety net goes to relatively low-income people. There are just a few exceptions, mostly child tax credits (which I counted as “universal” even if they phase out for the richest households) and Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend.

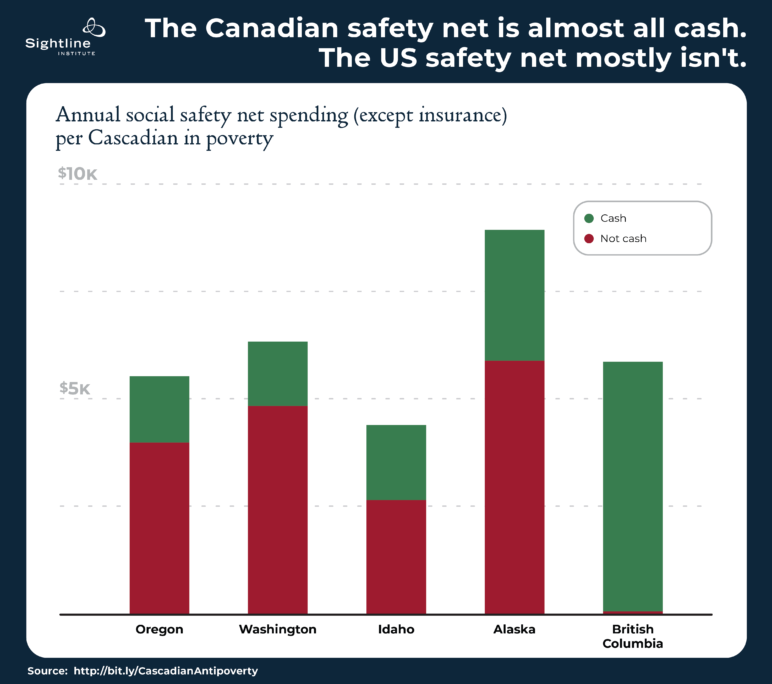

One last question: how much of this money is going out the door as money, and how much as vouchers or programs?

That turns out to be the single biggest difference between the countries.

As I wrote with my colleague Margaret Morales in May, Canada has already embraced cash as the single best way to help poor people.

The whole Canadian system is built on it. Low-income Canadians get a regular cash payment. Got a kid? That payment gets a little bigger. Spend more than a third of your earned income on rent? Bigger still. Also, you get an annual cut of carbon tax revenue, just like everybody else.

At least by this very rough measure—which, I’ll reiterate, is based on a different calculation of poverty on each side of the border—Canada’s cash-based safety net doesn’t actually add up to much more generosity than in the United States. But what its cash benefits do offer is flexibility. Instead of essentially giving poor Canadians a grocery allowance, Canada’s government gives you the choice of spending any given welfare dollar on groceries or on a trip to the dentist or a bike repair or whatever it is that you need most in a given month.

Where do we go from here?

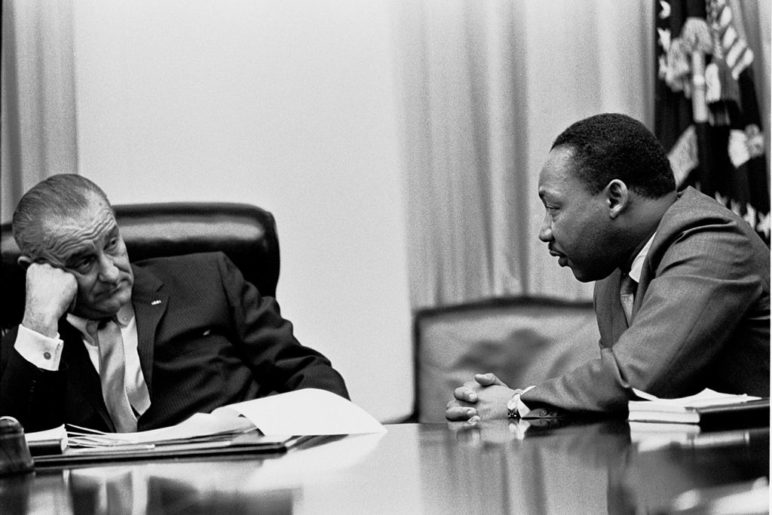

President Lyndon Johnson meets with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the White House Cabinet Room, 1966. Photo by Yoichi R. Okamoto, public domain.

Early in his 1967 book, King laid out a hard truth about his proposed shift in focus from civil rights to human rights.

“The practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap,” he wrote. “There are no expenses, and no taxes are required, for Negroes to share lunch counters. … The real cost lies ahead.”

In the years since King wrote that, public welfare spending has increased quite a bit, in both the United States and Canada—but much of that is from the rising cost of health care, which has fallen on public and private sectors alike. There’s a strong case that the U.S. still spends too little on the rest of its safety net, especially given its unusually high number of children in poverty.

For some Cascadians interested in pursuing King’s vision in 2021, the question may now be: What would it take to redirect some of that existing social safety net spending to cash?

Daniel Hauser, a policy analyst for the progressive Oregon Center for Public Policy think tank, argued in an interview that most non-cash benefits and programs exist for a reason, and that simply replacing them with equivalent cash payments could be very good for some but would hurt others.

“How to ensure that we’re not just shifting chairs on the Titanic?” Hauser asked. “That we’re not just moving around limited aid to poor people, leaving some of them worse-off?”

A different approach, of course, might be to cut other programs instead. For police abolitionists like Smiff, here’s one relevant figure: the Portland Police Bureau’s $245 million budget this year would be enough for a cash payment of $3,094—$259 a month—to every Portlander in poverty. No more; no less.

Another question might be: How can we ensure that future investments in our social safety net focus on giving people cash?

Various Cascadians are working on this. In Washington, the most prominent campaign is to belatedly fund and expand the long-promised Working Families Tax Credit, worth an average $350 per year to the incomes of about 30 percent of Washingtonians. In British Columbia, the leading promoters of a basic income, the Green Party, are out of provincial government for the moment but awaiting the results of the major study they won funding for. In Oregon, a proposed ballot issue in 2022 would create an “Oregon People’s Rebate” of $750 per person per year, paid for by boosting corporate minimum gross receipts taxes. That’d be enough to bring Oregon’s per-capita safety net spending up to Washington’s standard, and to give it a cash-benefits ratio larger than Alaska’s.

“Among the people who drafted this initiative together, a couple of the people in the room were actually homeless,” said Antonio Gisbert, the Corvallis-based chief petitioner for the Oregon People’s Rebate effort. “One of them said, I’ve never physically seen $750 together. I’ve never had access to that much money all at once.”

What Smiff said in July was right. Between some combination of its existing programs and additional taxes, our society does have enough money to give some of it to any of us who need it.

Maybe the path to King’s promised land of a guaranteed minimum income can be traveled in huge leaps like Yang’s. Maybe it’ll take small steps like Gisbert’s. In either case, 2020 seems to have shown that a lot of people are ready to start moving.

Zane Gustafson contributed research. Charts by Devin Porter. Thanks also to Margaret Morales.

Onesmus Mulima

Thanks so much and I appreciate your efforts to make sure the change is made up to the reality. This will make people feel like they are not left behind. Everyone will live life of abundance.

Cliff

It would be valuable to compare these numbers to the amount we pay people who are not in poverty. For example, how much do we spend in tax deductions on mortgages, charitable contributions, etc

The money is there, it just isn’t getting to the people who actually need it right now

Michael Andersen

Completely agreed.

Jeffery Smith

It’s a POV, that a UBI is a gov’t program, a creature of taxes and subsidies, that it must and only can come from public revenue. No such program lasts, or lasts long. The only real-world examples are rent shares. An alternative POV is that society has a surplus and that all members of society are owed an equal share. That surplus is the value of things having exchange yet exist without the input of anyone’s labor or capital. Things like land, especially downtown locations, and natural resources, especially oil, and government granted privileges, especially corporate charters and patents. Were governments to recover the annual market value of all those economic assets–their “rent” (technically)–it’d have many trillions to disburse to us all. Gov’t can recover rents not only via taxes but also fees, leases, and dues. The problem with a UBI is that it’s only a political creature and would soon wither away, not coming from surplus. The beauty of a Citizens’ Dividend is that it highlights not revenue but surplus, a rental value that grows, as MLK noted when citing Henry George, as society grows, as the economy grows, and as technology advances. Yes, we, not government, are rich and rightfully would share what’s already ours.

Jeffery Smith

Oops. Exchange _value_.

Nate Ember

Wonderful analysis, please keep it coming!