Avelina Cabantan, 84, has never had a driver’s license. Her husband always drove. But after he passed away in 2003, what she really needed was a home she could afford on her own.

Cabantan has seen her share of hard times. She grew up poor in the Philippines, at one point pawning her mother’s ring to afford a $10 document fee that would give her children a future in the United States. In Oregon, she found work at Tektronix and Nike. But after her husband passed and she retired, Cabantan couldn’t keep up with the $1,600 rent on their longtime apartment. For the next twelve years, she moved frequently, staying with friends and family and craving another stable home.

An early riser, each morning she walked over to see the construction of a new affordable housing development steps away from the Orenco light rail station in Hillsboro, Oregon, chatting with the carpenters. By then, Cabantan had applied for two other low-income housing projects but was told the waitlist was years long. Then, leaving church one day, she got the news that her application at Orchards at Orenco had been accepted. She wept with relief. The rent was only $603 per month.

Cabantan is one of the lucky ones, the one in four households that qualify for federal housing assistance that actually receive it. “I love living here,” she repeated frequently during our conversation. She plans to stay for the rest of her life.

Avelina Cabantan stands alongside her raised flower bed, at Orchards at Orenco. Photo by Catie Gould.

Stories like Cabantan’s make affordable housing popular across Cascadia amid the region’s housing crisis. In poll after poll, year after year, Northwest voters call homelessness a top issue and say the region needs more affordable homes. Which only makes it stranger that, even as Cabantan was moving into her forever home, her own local government was working to block more low-priced homes like hers from existing.

Why? The planning commission was insisting that something else needed to be built on the land instead of homes.

More parking spaces.

Excess parking spaces come at a cost: Housing for people

When Cabantan’s home was built, Hillsboro’s zoning code required every new home to provide 1.5 parking spaces. But data presented by REACH showed that even during the busiest times, similar affordable housing complexes averaged closer to 0.6 parked cars per household. REACH didn’t want to kill dozens of affordable homes in favor of dozens of parking spaces that would probably sit empty.

REACH requested to build 0.8 parking spaces per household, but an initially receptive planning commission turned skeptical over the course of approving three separate buildings. “We had to fight tooth and nail every step of the way to just get some reduction,” recounted Dan Valliere, Executive Director of REACH Community Development. At one point, even the Metro Council President and former Hillsboro mayor, Tom Hughes, weighed in, giving his full support to the parking reduction.

In the end, the housing complex was required to have 1.1 parking spaces per household. It knocked up to 30 homes off the project, recalled a city staffer.

Minimum parking requirements—ratios of how many parking spaces each building needs to have—were widely adopted in North America in the mid-twentieth century. Intended to provide a home for every car, these regulations frequently overestimate how much parking will actually get used. That creates a new host of problems.

Parking eats away at the buildable area of a site. It means fewer homes and less space for amenities like Cabantan’s garden bed, playgrounds, or walking paths. Bigger impervious surfaces also drive up the cost of managing stormwater and amplify temperatures during heatwaves. Each needless parking space hits a project twice: once in its direct construction costs, and then perpetually through the lost revenue of homes that weren’t built, increasing the public subsidy needed to maintain the building over time.

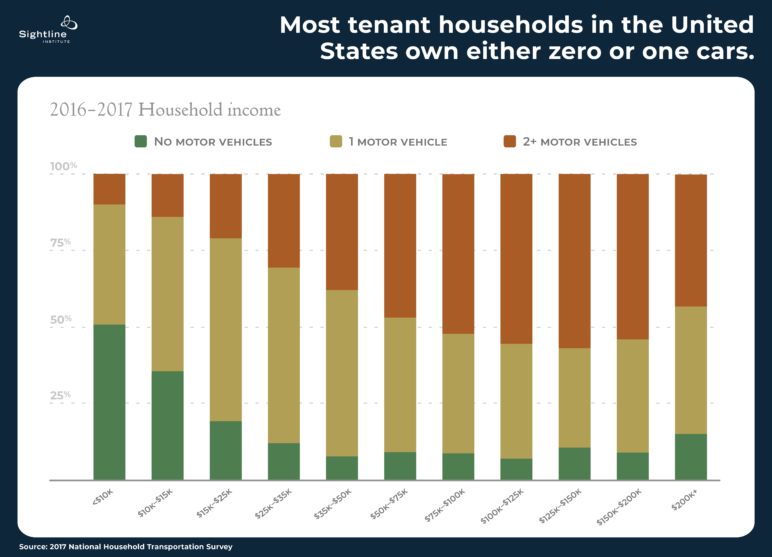

Households with the lowest incomes are also the least likely to need a parking space at all.

Data: 2017 National Household Transportation Survey.

Data from the Cabantan’s building in Hillsboro would show that only 67 percent of households who moved in owned cars, well below the citywide average. Every night, dozens of the free parking spaces sat empty, just as REACH had predicted they would.

“For sure, we would have had more homes,” recalled Valliere, if they hadn’t been forced to build more parking than needed.

The following year, Hillsboro amended its zoning code to avoid making the same mistake in the future, adding a carve-out for affordable housing near transit at nearly the same ratio REACH had initially requested. But these mandates are still on the books in many cities across Oregon, preventing more people like Cabantan from finding the affordable housing they need.

High parking requirements increase barriers to housing construction

In towns with excessively high parking requirements, it can be rare for affordable housing to be sited there at all. Catholic Charities of Oregon’s Good Shepherd Village housing development, proposed in 2021, which will provide 143 affordable homes for residents of Happy Valley, was the city’s first ever subsidized housing project. One reason? In Happy Valley even a studio apartment needs 1.25 parking spots, and requirements increase from there.

All in all, Happy Valley’s code required Good Shepherd to provide a whopping 1.7 spaces per household. The code does allow affordable housing to request exceptions but doesn’t specify any particular amounts, leaving developers subject to the discretion of city officials and unpredictable council votes. Late-breaking changes to parking or other major design elements can send a finished site plan on a long, costly trip back to the drawing board, explained Julia Metz, who navigated the permitting process for Catholic Charities. “The lack of clarity creates risk for a developer,” she said. “Risk in and of itself can cause someone to not even consider developing in a certain jurisdiction.”

Despite presenting parking studies from three comparable affordable housing projects in nearby Beaverton, which showed a peak demand of 0.68 parking spaces per home, Catholic Charities offered to build 1.5. It was a political calculus on their part, as they needed to request several zoning changes to make the project cost feasible. They had no way to guess what might work; after all, no other affordable housing developer had bothered to try.

State intervention would accelerate parking reform

Oregon is on the verge of freeing nearly all its future affordable housing projects from all of this.

This July, the Land Conservation and Development Commission will be voting to permanently adopt a new set of rules under the “Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities” initiative. Beginning in January 2023, affordable projects like Orchards and Good Shepherd would get to choose their own parking ratios. So would single room occupancies and homeless shelters, as well as all small homes and those close to relatively frequent transit.

One in four Oregonians spend more than half of their income on rent.

Nearly every city within Oregon’s eight largest metro areas will fall under the state’s new planning rules, putting affordable home builders back in charge of determining their own parking needs. So far, twelve organizations that develop affordable housing and provide supportive services have written in support of the rules.

“The parking requirements drive everything else in the design,” said Nick Sauvie of ROSE Community Development, one of the signatories. “Ultimately, requiring a bunch of parking reduces the amount of housing that can be put on the site.”

Any intervention that accelerates housing construction is badly needed. One in four Oregonians spend more than half of their income on rent. According to State Chief Economist Josh Lehner, half of the state’s current housing shortage—54,000 of the 111,000 units—is needed among those earning less than half the area median income (AMI), or about $40,000 per year. Oregon Housing and Community Services estimates that to meet demand for housing at that price point, construction of regulated affordable housing would need to triple for the next twenty years.

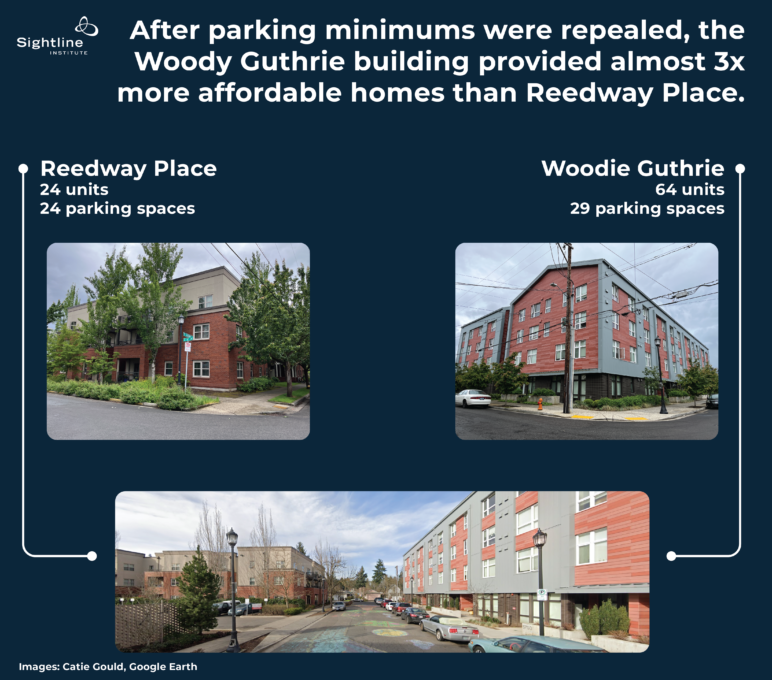

Optimism that changes in land use regulations can play a significant role in that growth might best be found at the intersection of SE 91st Ave and SE Reedway in Portland. First opened in 2004, Reedway Place provided 24 affordable homes for the neighborhood—with the same number of parking spots—exactly what Portland had required. “We had a pretty nasty NIMBY battle,” Sauvie remembered. “The parking complaint was a big deal.”

Since then, Sauvie has seen attitudes change as neighbors have gotten more used to multifamily and mixed-use development. Zoning codes have changed, too. In 2016, Portland waived parking requirements entirely for all residential buildings near transit that included subsidized housing. Two years later and just across the street, ROSE Community Development was able to provide homes for another 64 low-income families. The building, named after Woody Guthrie, could include 40 more homes (and just 5 more parking spaces) than Reedway Place, thanks to the code changes.

The end of parking mandates wouldn’t mean the end of parking. Every affordable housing provider interviewed for this story stressed how important it was to them to provide residents with the amenities they need to thrive, which usually includes some parking. But it would mean that dollars that previously went to unnecessary parking spaces could instead be put towards housing more people or more deeply subsidized rents. Properties that were previously unfeasible to build on could come back into play, increasing the number of developable lots in any given town.

Building an abundance of affordable housing would mean that other Oregonians wouldn’t have to spend a decade to find a stable home, like Cabantan did, after life takes an unexpected turn. She had no idea that her building was at the heart of a years-long fight over parking spaces that ultimately changed a law. Most people never hear about those types of proceedings, least of all the future beneficiaries. What she does know is that she is glad to spend her mornings gardening instead of worrying about moving again.

From Cabantan’s flower garden, the empty parking spaces in view are a stark reminder of all the people who still haven’t found a place to call home. May eliminating parking mandates get them one step closer.

Melvin Ray Farris

Gray’s landing apartment complex have a terrible ratio absolutely pathetic.