To dig out of Oregon’s housing shortages, build 36,000 homes a year for the next decade. It’s that simple.

Okay, maybe not that simple. That is, after all, a lot of homes, and land, and materials, and carpenters, and architects, and plumbers, and city permit review staff. It’s a lot more homes than the state’s been building the last few decades.

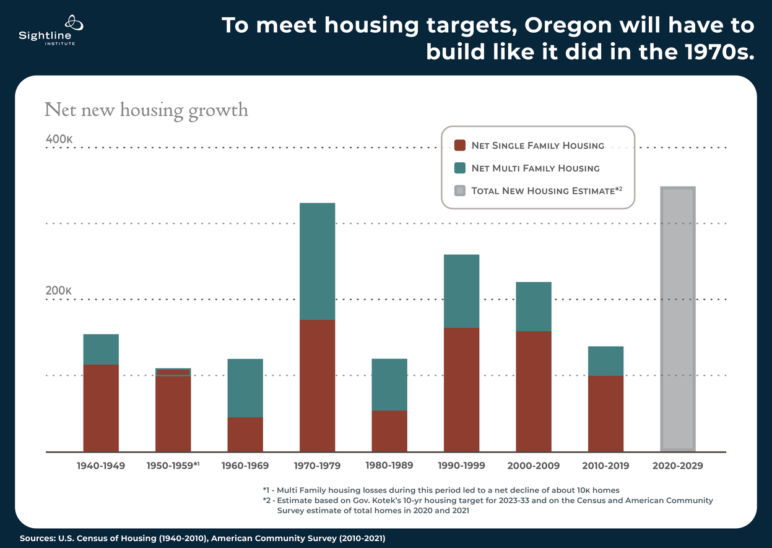

But that’s part of the problem that Oregon’s new governor, Tina Kotek, wants to address. The state hasn’t been building enough new homes to keep up with population growth over the last few decades. State analysts calculate that Oregon is 140,000 homes short of having enough for families, working people, seniors, and everybody else to find a place to live that meets their needs. And that’s not even counting the 220,000 homes needed just to keep up with future population growth and demand over the next decade.

It’s a big problem. To have a prayer of getting there, policymakers would need to swing for the fences.

So how does Oregon get there? A lot of people making small decisions, and a smaller number of people making some big decisions.

One of those big decisions could be House Bill 2889, an overhaul of state housing rules that would do two main things. First, it would set targets for housing production that are based on actual need, not just carrying forward recent patterns of homebuilding. These targets would consider price, location, and equitable outcomes, in addition to just the number of homes needed. Second, it would identify the barriers to homebuilding that state and local government can alleviate directly—everything from apartment bans to parking mandates to slow permit processing to roadway standards to environmental reviews.

Here’s the trouble: every one of those barriers exists for a reason, often a good reason. The point of HB 2889 isn’t to sweep them all away, even if that were possible. The point is to force government, at every level, to weigh the benefits of each barrier against its costs.

And what if Oregon did take on that huge task? Would it even be possible to build as many homes as Oregonians need?

It turns out that it would.

Back in the 1970s, a much smaller workforce built this many homes

The year is 1977. Bell bottoms reign, disco fever is high, the Blazers just won the NBA championship, and Oregon’s estimated 7,6521 residential construction workers are building 33,000 new homes.

The year is 1977. Bell bottoms reign, disco fever is high, the Blazers just won the NBA championship, and Oregon’s estimated 7,6521 residential construction workers are building 33,000 new homes.

This is a big number. Oregon added almost 330,000 new homes during the 1970s, almost three times as many as it built during the 1960s or 1980s.2 That’s not far off from the 348,000 homes that Governor Kotek wants the state to add by 2030.

And in the 2020s, Oregon will have some new advantages. For one, Oregon now has a private residential construction workforce almost three times the size of 1977’s: 20,227, as of 2021.3 Oregon’s total population is 4.2 million, more than double the 2.1 million residents the state had fifty years ago. It’s true that a lot of work needs to be done. But if Oregon could bring the barriers to housing back down to the level of the 1970s, its current and future workforce could find the time to do the job.

Oregon also has way more homes already in place, so 348,000 new ones by 2030 would be much less of a change to the existing landscape than it was in the 1970s. Those 330,000 additional homes in the 1970s were a 44 percent increase to the 745,000 homes that already existed in 1970. But now that the state has 1.8 million homes, adding 348,000 would mean less than 20 percent growth—pretty close to the growth rate of the 1950s, 1960s, or 1990s. If you live on a block with 20 homes, that might look like your neighbor on the corner converting their garage into a granny flat and a small apartment building going up two blocks over.

Why does it take a much larger workforce today to build a smaller number of homes? Whatever the reason, it’s not unique to Oregon. Last Sunday, a New York Times column about a new academic study on this question quoted construction industry veteran Ed Zarenski:

There are so many people who want to have some say over a project…. You have to meet so many parking spaces, per unit. It needs to be this far back from the sight lines. You have to use this much reclaimed water. You didn’t have 30 people sitting in a hearing room for the approval of a permit 40 years ago….

The work we do today takes hundreds more people in the office to track and bring to completion…. The level of reporting that you have to send to the government, to the insurance companies, to the owner, to show you’re meeting all the requirements on the job site, all of that has increased. And so the number of people you need to produce that has increased.

Again: the lesson here isn’t that rules are bad. It’s that every rule has a cost.

Oregon built a lot more apartments in the 1970s

Then there’s the issue of sprawl. News coverage of Kotek’s plan last week from The Oregonian and CityCast implied that Oregon’s rapid 1970s growth had been possible only because it happened before the state’s famous urban growth boundary (UGB) law took effect around the end of the decade.

Yes, it’s likely that the state’s new anti-sprawl law slowed homebuilding somewhat. But other changes were afoot, too.

Multifamily construction in Oregon soared in the 1970s, plummeted in 1980, and has never recovered. By the 2010s, the share of net new Oregon homes in multifamily buildings hit its lowest average in 60 years.

In part, that’s because the public backlash against what former Governor Tom McCall had called “coastal condomania” had also reached far inland. For example, as part of a national trend in the ‘70s, a major downzone banned apartments from much of inner southeast Portland. City leaders said their goal was to attract middle-income families to the area. One thing the downzone definitely did was push up the price of land per home. Today, it’s common to see the price of land account for more than half the value of a single-detached house in Portland’s walkable, transit-rich inner southeast neighborhoods.

More generally, local governments were institutionalizing a new level of scrutiny on additional housing. This wasn’t unique to Oregon; in California, the scrutiny was far more intense. Still, rules kept piling up.

Meanwhile, the government, whose subsidies accounted for 28 percent of multifamily housing starts across the United States in 1970-72, was pulling back from direct construction in favor of housing vouchers that had a less direct impact on homebuilding.

Economies are big and complicated. It’s impossible to say if the planning reforms of the 1970s contributed to the rapid decline in multifamily construction in Oregon after 1980. What’s certain is that they failed to prevent it. And because three-story wood-frame buildings are generally the least expensive type of structure to build, this decline had a profound impact on the state’s housing market.

Adversaries agree on Oregon’s need for speed within urban areas

Oregon’s urban growth boundary was established by only one of 19 new planning goals created by Oregon in the 1970s. Thanks to heroic efforts at the time, one of those goals (goal 10) was to build enough housing for people of all incomes. But even in residential zones that fall within Oregon’s urban growth boundary, state law doesn’t prioritize housing over any of the other goals.

Some think that should change.

“There’s been a concerted effort in both the legislature and [the state land use commission] to acknowledge that the primary purpose of land zoned under Goals 3 and 4 is farming and forest,” Dave Hunnicutt, executive director of the Oregon Property Owners Association, said Monday. “But we don’t get that same recognition on lands inside the UGB that are zoned for residential. And we should.”

Mary Kyle McCurdy, deputy director of the pro-land-use-planning nonprofit 1000 Friends of Oregon, has a slightly different take: that Oregon can reboot apartment construction by allowing apartments and other compact, less expensive housing options on more land without de-prioritizing other goals.

“We have sufficient land inside urban growth boundaries that we are inefficiently developing,” she said Monday. “Surface parking lots, sprawling one-story office buildings with expanses of grass that nobody is using for anything.”

Though McCurdy and Hunnicutt have been adversaries for decades over the state’s urban growth boundary, both are supporting House Bill 2889 alongside affordable and for-profit housing providers, environmental justice organizations, the Fair Housing Council of Oregon, and Sightline.

“I think where Mary Kyle and I would agree is regardless of where the housing is built or how we do on land supply, if we can’t get it built in an efficient and timely and cost-effective manner, then it just doesn’t get built,” Hunnicutt said.

The first hearing for HB 2889 is today, but there are still many details to be hammered out about how to make building more efficient. Some of those details will be added to the bill soon. Many others will be worked out by the state government over the next few years, should the bill pass.

For that work to fully pay off, policymakers would need to keep focusing on a fundamental goal: making homes simpler and less expensive to build, one way or another. Making things a little more like the 1970s.

H. Pike Oliver

Great piece! The productivity issue is big. I posted your excellent analysis to Post.News — a great alternative to Twitter.

https://post.news/article/2LStDzOzEengD2Ro158zYUzPIFH

Davd Yaden

An excellent example of Sightline at its best: clear, rigorously analytical, timely and topical.

Chris Jones

I live in Eugene-Springfield, and my perception is that we have had a multi-family housing boom during the past ten years. But looking at the data from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EUGE641BPPRIV shows that we are only running at about half of the needed rate over the last three years.

The Eugene-Springfield MSA is about 9% of Oregon’s population, and according to the Fed’s data, we have had 4,800 new housing units authorized in the past three years. To build our share of the 36,000 new units needed, we would have had to build 9,700 units in those three years. The current pace is not terrible, but it looks like we need more. Maybe the changes in minimum parking requirements will motivate some additional building; the statistics released recently by the City of Eugene about ADU permits show only a tiny effect, if any, from the “middle housing” rule changes.

Tom Civiletti

Perhaps the larger number of residential construction workers today in Oregon build fewer houses because many of them are doing remodeling and repair of existing residences. Not only do more buildings increase demand for workers, but reduced do-it-yourself construction increases demand for pros. I’ve heard from many people that the wait for a remodeling contractor is often many months.