The trouble all started at a city council meeting in August 2022. An affordable housing developer was unveiling a potential project.

It was happening in Washougal, a town of about 17,000 in housing-strapped southwest Washington. In the chain of events that followed, the city lost roughly 40 future affordable homes and may have accidentally blocked any future downtown apartments from being built under the new code.

“It will make future projects incredibly difficult, if not impossible,” said Matt Edlen, whose firm is in the midst of constructing a six-story building that will add 46 new homes to Main Street. It’ll be one of the last projects built under the old rules. “Anything like that just stops.”

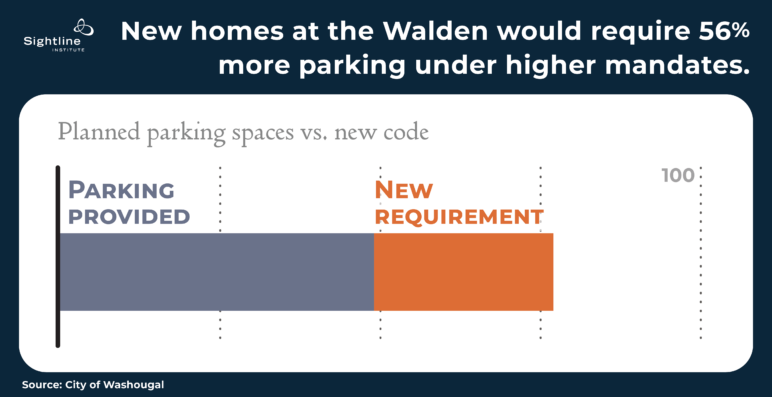

The Walden building coming to downtown Washougal at Main St and Pendleton Way would need 56 percent more parking spaces to be permitted under the new code. Image by Edlen & Co. Used with permission.

Local zoning codes, the thick binders of monospaced text that shape how modern cities are allowed to evolve, are often thought to be carefully crafted regulations that are uniquely tailored to each town’s history and needs.

But Washougal’s story shows what often happens instead. Key regulations that limit how many homes can be built on any given lot are simply copy-pasted from one place to the next based off of what feels right, with scant research into the origins of those numbers or how they fit into the local context.

When this mood board regulating new construction becomes too prescriptive, one false move by people with the best intentions can do dire economic damage. The rules can also become so complicated that even a trained city planner can easily misinterpret them. That’s exactly what happened in Washougal.

How a parking mandate is born

“Council really liked the project, but the question of parking came up during part of that presentation,” recounted Mitch Kneipp, Washougal’s community development director. It was still early in the process, and the Vancouver Housing Authority (VHA) hadn’t yet finalized exactly how many subsidized homes or parking spaces it planned to build. But if it went forward with 80 new homes, council members learned, Washougal zoning code required only 40 off-street parking spaces.

Nobody had ever built to that ratio. Since Washougal had set that parking minimum in 2006, every downtown developer had voluntarily provided at least one space for every home. But if someone actually were to build to that minimum allowed ratio of 0.5 spaces per home, “that’s going to create a demand for parking that is—in their opinion, not acceptable for the city,” described Kneipp. The council tasked Kneipp with increasing the parking requirements. “So that’s what we did.”

Washougal, like most cities, started by looking at its neighbors around the county. Ridgefield mandated at least 1 parking space per home. Battle Ground required 1.5, like Washougal did in areas outside of its downtown core. Out of the other cities in Clark County, only the much larger city of Vancouver, Washington, gave more flexibility over parking spaces.

Not wanting to be an outlier, in August 2023 the Washougal city council voted to increase residential parking mandates in its downtown to match those of neighboring Camas: 1 space per studio, 1.5 spaces per one-bedroom, and 2 spaces for homes with two or more bedrooms.

Unfortunately, Washougal officials had failed to notice a snippet of code that relaxed these mandates for multifamily housing projects—provisions that were critical to making apartments financially feasible.

Parking flexibility was critical for new housing in downtown Camas

It’s easy to see why any town would want to copy what Camas is doing. The former mill town of 27,000 has reinvented itself in recent decades, attracting new businesses and the highly paid workers that come with them. This October, Camas was selected as one of eight semi-finalists for the national Great American Main Street award, recognizing the Downtown Camas Association for its work reducing commercial vacancy rates from 60 percent in 2009 to less than 1 percent today.

“When I first opened a store in 2004 there was not much going on,” said Carrie Schulstad, executive director of the Downtown Camas Assocation. “We had plenty of parking, because there weren’t people.” For decades, there were only 32 homes downtown. That number doubled in 2020 after the opening of the Clara Flats building with 30 new residences. Another building about to break ground, named Hudson East, will add 56 more.

Left: Clara Flats in downtown Camas. Photo by Catie Gould. Right: Hudson East building. Image by Cascadia Development Partners.

Washougal thought it was copying Camas. But neither of those buildings would be legal to build under Washougal’s new code, which would require each to be surrounded by a big parking lot.

Washougal’s planners had missed that for many years, Camas’s code has contained a unique and complicated rule that effectively cuts parking minimums for multistory buildings by half or more. Where that exemption came from is anyone’s guess. But without it, neither of the town’s new downtown housing developments would have been allowed.

Thanks to the snippet that discounted the upper stories from the high parking requirements, the pair of new buildings only were required to have 0.6–0.9 parking stalls per home.

To Schulstad, buildings like these are exactly what a healthy modern downtown needs. “In the Main Street world, you want lots of people living downtown,” she said.

Washougal builders grapple with town’s new parking ratio

The increased parking mandates run contrary to the vision Wes Hickey has long had for downtown Washougal. His aim was to create a vibrant city center rather than more strip malls on the outskirts of town, and he has been working for decades to make it happen. His company, Lone Wolf Development, built the iconic Town Square building in 2007, among several others.

“This decision does not seem like it was really thought out,” he said about the policy change. “There was no discussion of ‘how does this impact anything’ or ‘is this helpful to move downtown redevelopment forward’.”

“I am not able to envision what any private developer could build in downtown Washougal right now with their current parking requirements,” said Hickey.

Victor Caesar said the new rules will force the VHA’s tax-subsidized affordable housing project to house fewer people than it would have. Due to the August code change, VHA has pivoted from an initial goal of 80–90 units of workforce housing down to just 40–50 homes for seniors, in part because Washougal still allows lower parking ratios for senior housing.

The homes are sorely needed. Half of renter households in Clark County are considered rent-burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

In response to the city’s inquiry into parking minimums, the VHA prepared a capacity analysis to show the city what a higher parking ratio would mean. The site, which covers three-quarters of a city block, could fit a maximum of 40–45 parking spaces on the ground floor. To meet higher parking ratios, the building has no option but to shrink.

A parking garage, which officials from the city suggested the VHA could consider, was out of the question. “I’ve worked in real estate and affordable housing for almost a decade now,” Caesar said. “There’s just no way you can get a parking garage to pencil.” A multi-level structure can cost upwards of $80,000 for each parking space.

Even the market-rate Walden building, currently under construction a block away from the VHA site, can’t shoulder the cost for a multi-level parking garage in the small-town market. “Mass excavation, shoring costs, water considerations. All of these things make going down [to build underground parking] very, very expensive,” explained Edlen. Building multiple levels of parking above ground wasn’t a good option either, due to overall building height restrictions. More floors dedicated to parking means fewer floors remaining for housing and other uses that actually make money for the building. “You’ll never recoup what you spent on the parking stall based on what you can charge for parking,” said Edlen. The cost—hundreds of dollars in additional rent per month to finance each parking stall—gets passed on to the tenants upstairs, whether they use the parking or not.

“That is going to make development really challenging,” Edlen said about the increased requirement. “That’s the kind of parking ratio that you would have seen 20 years ago.”

The only way Edlen could fit a parking space for every home in the downtown Walden building was through a mechanical stacking system that fits three cars into the space of one. The system costs roughly $30,000 per parking space. But even accounting for the fancy mechanical car stacker, the building would still be 20 parking spaces short of the new requirements. This project was lucky. It had already gone through permitting before the change. But without special permission to deviate from the zoning code, it wouldn’t be allowed again.

In other cities, Edlen might be able to provide additional parking by leasing spaces from a city-owned lot nearby. Washougal has no such lots available. Ironically, the desire to avoid having to build a public parking facility in the future was one of the primary reasons that the council increased the off-street parking requirement in the first place, effectively shifting the cost of presumed parking needs to the private market.

In practice, high parking mandates—like the 1.5 spaces per home required outside of downtown Washougal—require acres of land for surface parking for projects to be viable. Sites this large are rare to find in the city center. Washougal’s Ninebark apartments, which opened in 2023, provided 1.6 parking spaces per home. Residents will need cars for daily life here. Its location far from downtown means it only has a walk score of 20.

Under the new city code, if the complex was located downtown where residents might not need to drive for every trip, the project would require even more parking than it has now.

The Ninebark Apartment’s 1.6 parking spaces per home wouldn’t be enough to meet the new downtown parking minimum. Image by Ninebark Apartments. Used with permission.

Caesar is still exploring options for the VHA project, including purchasing a nearby property for surface parking or securing a slightly lower parking ratio through a development agreement with the city. A discretionary approval is not as good as a by-right allowance, though, Caesar explained. The project loses points on funding applications, and the agreement is subject to change with a shift in the political winds. But with parking mandates so high now, such agreements are likely to be the only way any new housing will be feasible to build in downtown Washougal.

Unfortunately, Washougal is not unique

Setting parking requirements is more of a political activity than a professional skill, professor and parking economist Donald Shoup writes: “I have never met a city planner who could explain why any parking requirement should not be higher or lower.” Planners, he insists, are winging it.

Case in point: Washougal’s story is unfortunately not the exception but the rule. “A lot of jurisdictions kind of rely on each other,” Camas planner Robert Maul replied when asked where his city’s parking minimums originated.

The hyperlocal politics of parking incentivizes cities to participate in this game of telephone. Every single trip a driver takes must both start and end in a parking space, providing an abundance of opportunities for frustration and panic at the prospect of not finding one. The housing that goes unbuilt—and the anguished calculations of those who find they can’t afford to live where they want—are invisible by comparison.

In any given town, only a handful of builders and city staff might know the extent of the damage.

Indeed, the high parking requirements that threaten future housing in downtown Washougal prevail across Washington. Pasco requires 2 parking spaces for every home. So does Puyallup. Even for studio apartments, where tenants forgo a bedroom for cheaper rent, Auburn and Bremerton require 1.5 parking spaces apiece; Lynnwood requires 1.25. At that ratio, builders must dedicate as much land to parking cars as to housing residents. This, in a state that has calculated it needs to build 1.1 million more homes in the next 20 years to address its severe housing shortage and high rents and prices.

In recent years, cities and states have increasingly been reducing or removing their parking minimums in order to reduce red tape for sorely needed housing. This past year Spokane eliminated residential parking mandates for the vast majority of the city. Across the border in Oregon, nine cities have eliminated their minimums citywide to comply with new state land use rules.

Washington does have some guardrails in place to protect new housing from excessive parking mandates. In 2019 and 2020, the state capped how much parking cities can require for certain affordable housing, homes for seniors and people with disabilities, and regular market-rate multifamily homes. But those protections only apply within a short distance of frequent transit, as if those are the only locations that a parking mandate can possibly be set too high. Smaller communities like Washougal and Camas don’t qualify.

Kneipp said that in the next year-and-a-half, Washougal will likely conduct a parking management plan for downtown. Maybe after that, its council will be moved to re-lower parking mandates, making new downtown housing possible again.

“Downtown is where we need to look at getting the density,” Kneipp said. “This is where we have our services. It’s much easier to build here than up on the hill, put in bigger pipes and everything else.”

That growth won’t be possible if new housing is hamstrung by parking every time. “I believe we are going to have to change regulations again,” Kneipp said. “I don’t think there’s a way that we can get away from it.”