A Federal Child Credit, Explained

Sightline’s case for cash support to families.

A federal child credit—a monthly payment of $250 to $300 for every child in the US—would be an epochal victory in the fight to house vulnerable Americans. The payments, which under some proposals would phase out for the wealthiest families, would be far less than the cost of raising a child. But $250 to $300 per month happens to be very close to another number that represents the single largest expense of parenting: housing a child.

A federal child credit—a monthly payment of $250 to $300 for every child in the US—would be an epochal victory in the fight to house vulnerable Americans. The payments, which under some proposals would phase out for the wealthiest families, would be far less than the cost of raising a child. But $250 to $300 per month happens to be very close to another number that represents the single largest expense of parenting: housing a child.

And that is one way to think about these proposals. They’re basically the equivalent of a massive boost to the federal housing voucher program, specifically for households with kids.

Except these proposed benefits are much, much better.

Cash payments give households the flexibility to respond to their needs in real time.

Most welfare programs in the United States, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—commonly referred to as food stamps—and Section 8 housing vouchers, restrict how recipients can use the benefit. Because they’re so specific, they seem to be carefully targeted. But the truth is the opposite: they’re actually blunt instruments. A direct cash payment, in contrast, is a wire brush: fine and endlessly flexible, giving each recipient full control of their budget and the ability to tailor spending to an infinite variety of circumstances.

One person poor enough to qualify for a housing voucher might have access to affordable housing thanks to an uncle’s basement apartment, so would prefer to put the voucher’s value toward online classes to boost skills and launch a new career. Someone else who qualifies for SNAP might have access to nutritious food via community services, but could use the value of some SNAP dollars to cover childcare, pay for a necessary car repair, or even build personal savings.

Like a tree twisted by a shadow above it, everything about anti-poverty policy in the United States has been shaped by the unusual decision not to give poor people cash.

The impulse to micromanage the household budgets of the poor gradually created a vast array of valuable but convoluted social programs, separately applied for and maintained at incalculable burden to their recipients.

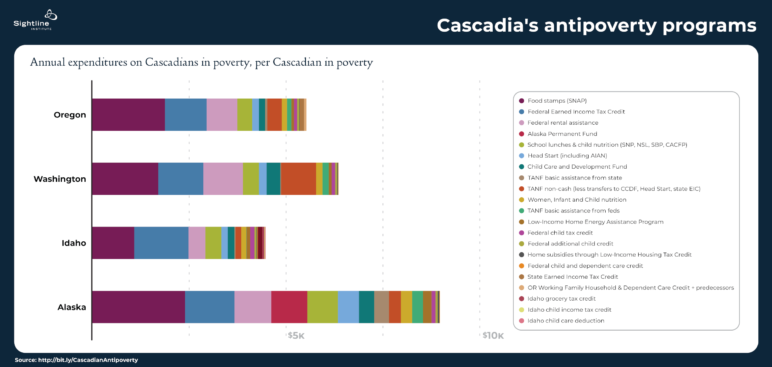

Bars represent annual state and federal spending on each universal cash program per resident of each state, plus annual state and federal spending on each means-tested welfare program per person living beneath the poverty line in each state. See this article for more details. Data, from many sources, is here, along with an interactive version of this and other charts. But in early 2021, the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan opened the door to an alternative approach to future expansions of the US social safety net: giving people money and letting them decide how to use it.

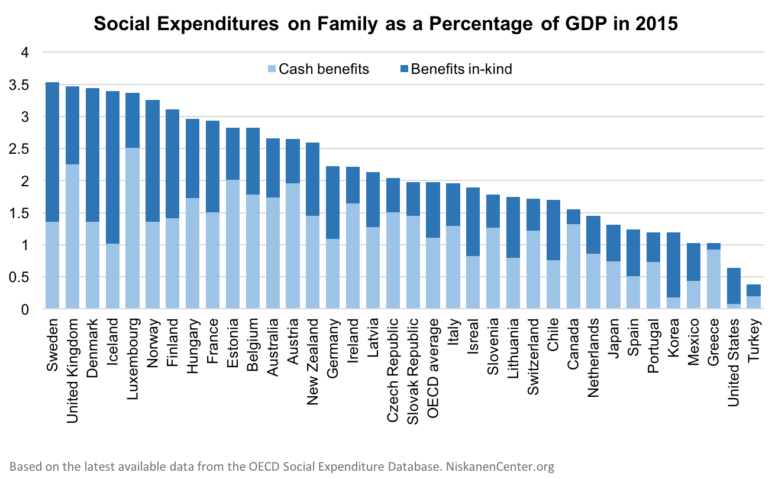

The United States currently has one of the highest child poverty rates in the rich world. That’s largely because most mid- to higher-income countries dedicate much more of their national wealth (more than 3 percent of all economic activity in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia) to helping their youngest residents begin their lives.

The United States is even more unusual in its singular unwillingness to give children cash. You can see this in the light blue bars below: no other country in the chart gives out less cash to families with children as a share of its GDP.

Source: Niskanen Center.

One reason cash credits for families with children are popular around the world is that they function as efficient, flexible housing subsidies for people who need them most: poor kids. Like automatic voucher eligibility, cash payments soften the blows of bad fortune that are beyond any kid’s control.

In Oregon and Washington, the average Housing Choice Voucher household gets $661 a month. But it’s of little help to most poor families in both states. More than 80 percent of households in poverty in those states don’t get Section 8, as the program is known, even if they meet its requirements. Seattle’s housing authority hasn’t been able to accept a single new name onto its voucher waitlist in four years. In Portland, it’s been five years.

The 2021 federal child tax credit gave a two-child family almost that same amount—$500 to $600—in monthly cash. But the credit was better than a voucher expansion in the following ways:

- This benefit was available to everyone eligible, the way Section 8 vouchers never have been. There were no waitlists and no process of signing up for a waitlist.

- You didn’t risk losing it if you moved.

- You generally didn’t lose it—and risk going through the years-long waitlist process again—if you got a raise or a new job.

- You could use it on a mortgage just as easily as on rent.

- Your landlord or seller didn’t need to go through any special process to accept your payment. It was just a check like any other.

- You could spend it on whatever your household needed most in a given month, not just housing: a hospital visit, a car repair, a preschool.

Helping families with kids cover their additional housing costs isn’t a new or radical idea. It’s almost exactly how rental subsidies work in Canada, where the Rental Assistance Program is a monthly cash payment to tenant households that include children.

“Anyone who’s a tenant advocate or a renter should be intrigued by this proposal and wanting to engage,” said Kim McCarty, executive director of Oregon’s Community Alliance of Tenants, in 2021. “Families could have support from their government that is more dignified, less intrusive, more comprehensive.”

If you don’t enjoy filing your taxes each year, please imagine trying to get around to it while dealing with an eviction. Or trying to document your income from five different gigs, two of which were paid in cash and three of which ended months ago. Or trying to do it from jail. And let’s add that in each of these scenarios, you’re a single parent.

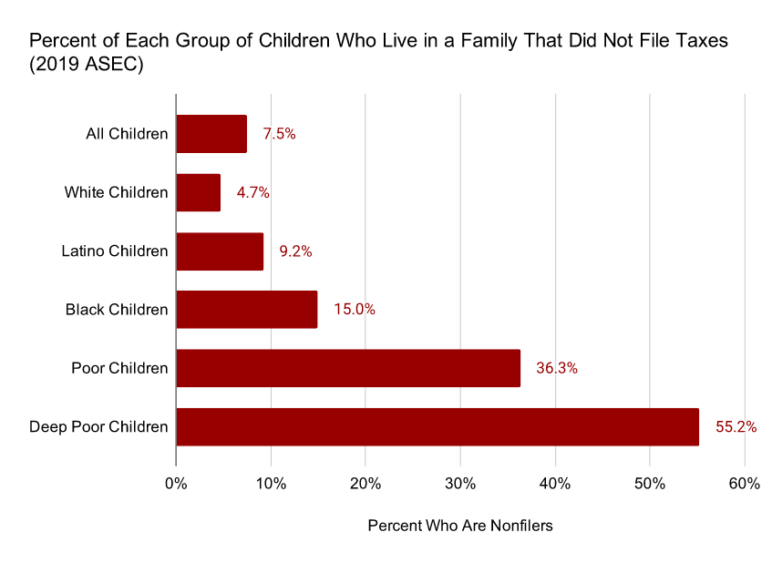

Scenarios like those are part of the reason the demographics of children in US families who didn’t file taxes last year look like this:

Half of US kids in deep poverty live in households that don’t file taxes.

This is why it is not a good idea for cash benefit programs intended to help poor people to send cash only to people who get around to filing their taxes. It’s not a poor kid’s fault that their parents tend to have a lot of other things to deal with.

The 2021 US child tax credit wasn’t a perfect policy, but it was a sensible step in the direction taken by almost every other rich country in the world, including Canada. If we want to keep our most vulnerable children housed, we can learn from both its successes and its shortcomings.