Series: Making Sustainability Legal

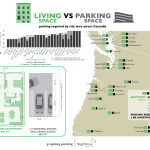

Some of the smartest, most innovative solutions for a sustainable Northwest are, at present, simply illegal. Believe it or not green treatments for polluted runoff, backyard cottages, and paid car-sharing are, in many places, against the law. There are dozens–maybe even hundreds–of similar examples. This Sightline series puts the spotlight on cases where we can make sustainability legal by changing existing regulations and developing pragmatic money-saving proposals. We can single out outdated rules and present smart solutions that align with today’s reality. Clear away this sort of debris, and the Northwest can grow into a region that’s more affordable, fair, and sustainable.