Series: Metro Matters

Bus passengers, 2001 by Seattle Municipal Archives used under CC BY 2.0

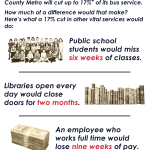

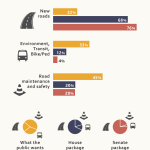

King County voters will decide on April 22 whether to approve Proposition 1, which would make needed investments to fix local roads and prevent a 17 percent cut in bus service. It’s a critical investment in the region’s future, and a fitting choice for Earth Day. Because slashing transit is one of the quickest ways to turn a region with healthy growth in transit ridership—which takes cars off the roads, gives people choices, and accommodates growth without adding to pollution and traffic and health burdens—into a region where people simply give up and get back in their cars.