Author’s note:The graphs in this post were updated in August 2015 to include the most recent available data.

When British Columbia enacted a carbon tax shift in 2008, many thought other jurisdictions would follow soon with their own ways of cashing in their carbon. Seven states and four provinces were working out the details of a huge carbon cap-and-trade market called the Western Climate Initiative. Candidates Barack Obama and John McCain were campaigning for president with promises of clean energy on the double quick; Senator Obama even pitched carbon pricing in his stump speech. Ottawa was murmuring about following the lead of Washington, DC, with a carbon cap or tax of its own.

Then history took a turn: financial collapse, bailouts, Tea Party, climate science denial, 2010 midterms, the fiasco at Copenhagen. The front in the war on climate disruption shifted from grand policy to fighting Keystone XL, coal trains, and other dirty-fuel infrastructure. Momentum abated for comprehensive laws at the state, provincial, and federal level that would gradually but persistently wean companies and households from fossil fuels by charging a small but rising fee for carbon pollution.

British Columbia then found itself alone: the only jurisdiction in North America with an appreciable, economy-wide price on global warming emissions. With this post, we launch a new series of articles on pricing carbon in Cascadia. Our ultimate focus will be Oregon and Washington, which sit between British Columbia, with its carbon tax, and California, with its new carbon cap (which we’ll discuss another day). But the best place to begin is where Cascadian carbon pricing began: in Canada.

What’s the latest on what BC’s carbon tax shift has done to carbon pollution, the provincial economy, and public revenue?

1. Pricing carbon has reduced carbon pollution.

BC’s carbon tax shift launched on July 1, 2008, with a rate of $10 per ton CO2. It increased by $5 per ton each year through July 2012, when it reached $30 per ton. Since then, the province has arguably been waiting for other jurisdictions to catch up, so that fossil-fuel price differences do not become too large between British Columbia and other places. The tax has therefore stayed at $30 per ton—about 30¢ per gallon of gasoline or 15¢ per therm of natural gas. The tax applies to almost all fossil fuels burned inside the province. Certain agricultural sectors are exempt (see page 23), and by definition the tax does not apply to carbon emitted at non-BC power plants that zap power into the province, to “process emissions” from industries such as aluminum and cement manufacturing, and to fuels for planes and boats that cross provincial borders.

When you tax something, you get less of it. That’s the point of taxing carbon pollution. What’s happened to emissions in the province?

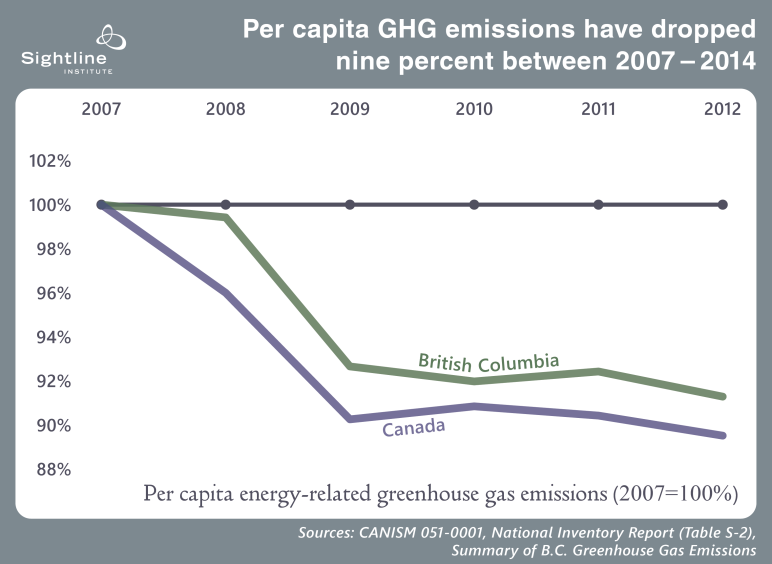

Energy-related greenhouse gas emissions in BC dropped by six percent overall (and nine percent per capita) between 2007 and 2011 (the latest year for which data are available).

Carbon pricing skeptics might note that emissions have also fallen elsewhere in Canada, and they have. In fact, between 2007 and 2011 Canada’s energy-related emissions fell by an equal amount.

But the carbon tax shift was not the only thing happening—far from it. Other forces have also trimmed emissions, such as widespread fuel-switching from coal to gas in much of Canada. These electricity-related changes have had little effect in BC, though, which gets almost all of its electricity from hydropower. Meanwhile, some trends, such as the Great Recession, have suppressed emissions, while others, such as the natural gas boom in northern British Columbia, have boosted emissions. BC’s tax shift is one influence among many.

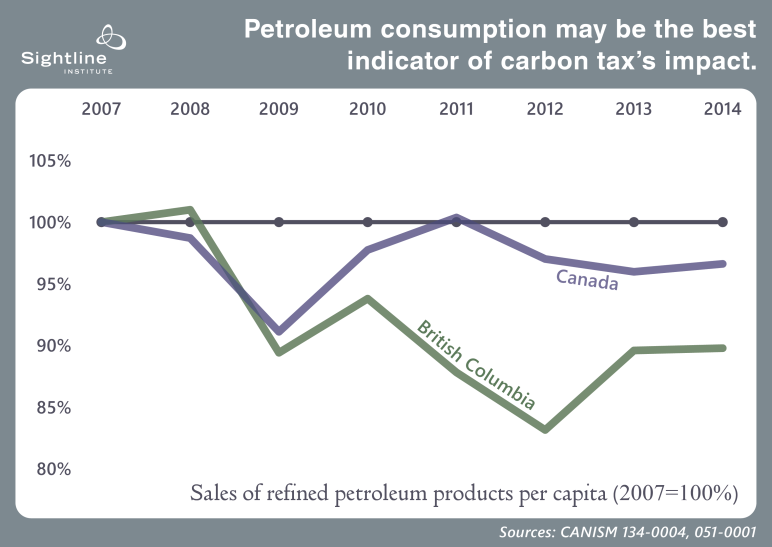

Petroleum products consumption—a trend less complicated by other factors than electricity or industrial emissions—may be the best indicator of the influence of the tax shift on carbon pollution. The province’s per-capita combustion of motor fuels and other petroleum diminished by 15 percentage points in the first four years of the tax shift—10 full points more than in Canada overall.

2. The carbon tax shift has not hurt the economy.

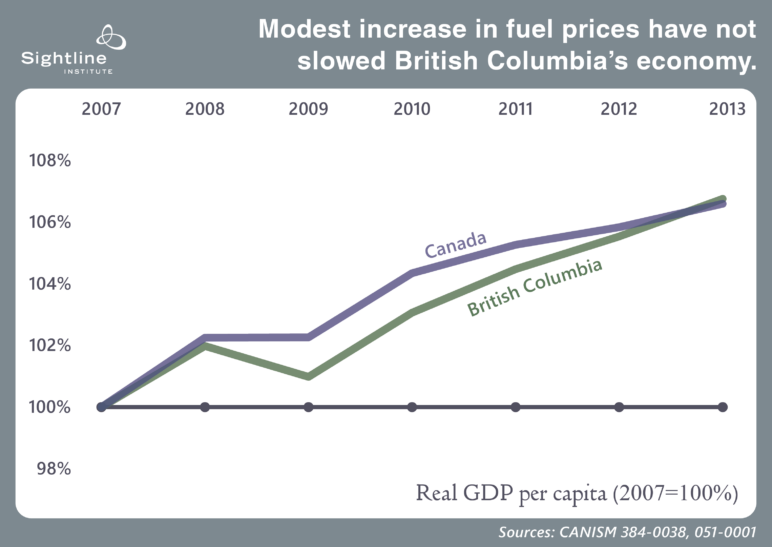

Economies are whipsawed by massive forces all the time. The carbon tax shift has raised the price of petroleum products and natural gas by around 10 percent—less than their prices normally vary in a year anyway. Meanwhile, it’s reduced corporate and personal income taxes. Economic theory suggests this swap of taxes will not hurt the economy and may even help. Some studies suggest that BC’s carbon tax shift in particular will eventually give B.C. an economic boost.

Still, you wouldn’t expect to be able to discern much of an economic impact in aggregate statistics. After all, since the carbon tax started, the province has been rattled by a global financial meltdown, the bursting of a gigantic housing bubble in the United States (the principal market for BC commodities), a boom and then a slowdown in China (another principal market for BC goods), and cascading economic debacles in Greece and other parts of the Euro zone (a third major market for BC exports). The effects of a gradual, modest increase in fuel prices, offset by reductions in income taxes, are almost guaranteed to be lost in the noise of these other trends.

What is detectable is that BC’s economy has roughly matched the Canadian economy overall in GDP growth; the economy has done just fine.

3. Pricing carbon has not caused inflation.

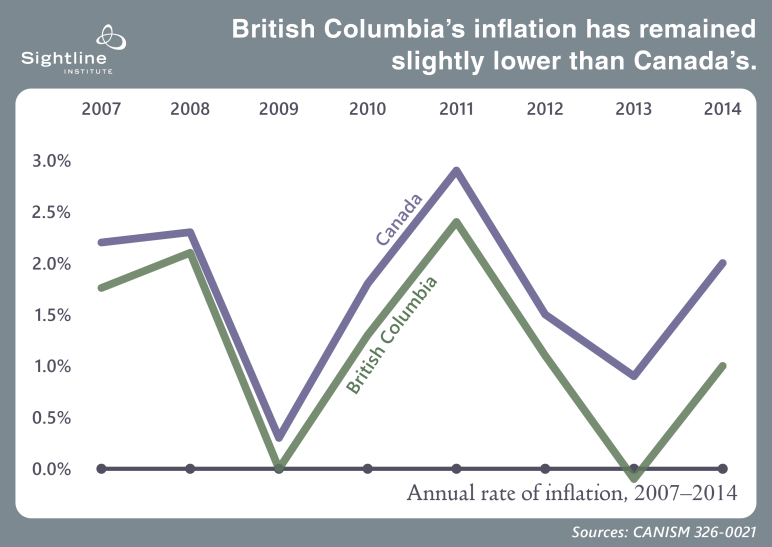

Will raising fossil-fuel prices drive up the price of everything else, triggering inflation the way that the oil price spikes of the 1970s did? No. On inflation, BC has done no worse than Canada overall. As the chart shows, inflation was lower in British Columbia than in Canada as a whole in 2007, before the tax shift started, and it has stayed lower ever since, neatly paralleling the national average a portion of a percentage point lower.

4. The carbon tax shift has been revenue neutral.

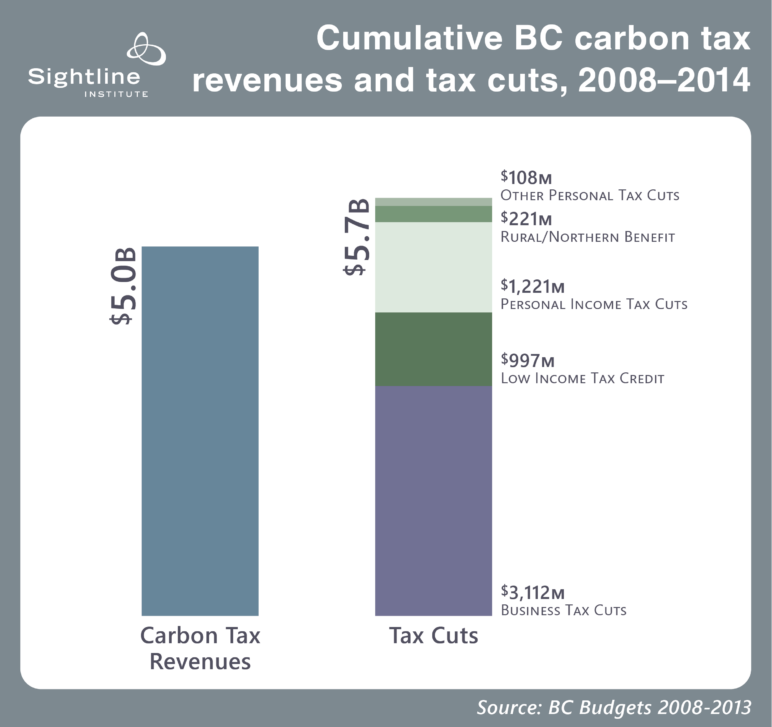

By law, carbon tax revenue must go back to citizens and companies as tax cuts (see page 64): “tax reductions must be provided that fully return the estimated revenue from the carbon tax to taxpayers in each fiscal year.” In practice, the tax shift has actually reduced tax revenue slightly overall: the carbon tax raised $1.1 billion in the fiscal year ending in 2013, for example, but offsetting tax cuts lowered other treasury receipts by $1.4 billion.

This chart shows revenues for the first six years of the program, during which net revenue declined by $700 million. The goal of the policy was not to reduce revenue, but the province has overestimated carbon tax revenue and therefore reduced other taxes by more than necessary to maintain revenue-neutrality.

5. BC’s carbon tax shift is not perfect.

BC’s carbon pricing system has flaws.

First, although BC’s carbon tax shift made low-income families whole in its early years, it has since become mildly regressive. An expansion of tax credits for working families would make them whole again.

Second, the carbon tax shift is not likely to get the province all the way to its ambitious emissions reductions goals for the later years of this decade. In fact, carbon tax revenues (and the associated carbon emissions) are expected to begin rising now that the carbon price has stopped stepping upward each year to counteract the effects of population growth and economic growth.

Third, the value of offsetting tax reductions is expected to grow faster than are carbon tax revenue. In other words, the shift is yielding a revenue gap that’s gradually growing.

All three of these issues could be addressed by returning to annual $5 per ton increases in the tax rate. This would help keep carbon pollution on a downward trajectory and at the same time would generate additional revenues that could be split between closing the revenue gap and providing additional tax reductions for low-income households.

Still, BC’s carbon pricing system is the best in North America and probably the world. The province has finished the nitty-gritty work of drafting statutes and regulations to implement the system. Oregon and Washington could do worse than to copy them, word for word, into their tax codes, then make adjustments needed to match circumstances. (Washington, for example, cannot rebate the carbon tax revenue through its income tax, because it does not have one. Instead, it could reduce sales and business taxes and provide rebates to low-income families, perhaps through the Working Families Rebate.)

Comments are closed.