Editor’s note: This is the second of three articles discussing the major challenges—planning, paying for it, and permitting—to building the transmission lines needed to transition to a cleaner energy future.

Transmission lines cost a pretty penny. Take for example the only new regional transmission project that will break ground in the Northwest anytime soon. Idaho Power and PacifiCorp’s 290-mile Boardman to Hemingway line will cost more than $4 million per mile, for a total of $1.2 billion. And that’s hardly the steepest line in the works in the United States right now; developers anticipate footing multibillion-dollar bills for several large transmission projects outside Cascadia.1

Most incumbent transmission developers in the Northwest, namely the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) and investor-owned utilities (IOUs), balk at building projects sporting these price tags.2 BPA shies away from large investments that would require it to raise rates on its public power customers and assume additional federal debt. And most IOUs fear tying up billions of dollars for years or even decades only to risk state regulators ultimately not allowing them to recoup their investment. As a result, neither BPA nor IOUs are investing in the grid infrastructure Cascadia desperately needs to decarbonize.

But if building transmission lines is expensive, not building them is exorbitant. Total decarbonization costs could rise by up to $13 billion if the Northwest does not expand transmission capacity. And unless Cascadia builds a grid that can support the end of climate-destroying fossil fuels, we will pay the highest price of all in the form of more devastating wildfires, oppressive heatwaves, and dangerous droughts.

All Northwest leaders can help untangle the financial impediments to building new lines. Washington senator Maria Cantwell and the Northwest congressional delegation can pressure BPA to deploy more low-cost federal debt to the cause. The Oregon and Washington state legislatures can set up state entities to partner with private non-utility transmission developers. Oregon governor Tina Kotek and Washington governor Jay Inslee can initiate the development of a multistate cost allocation agreement to offer IOUs greater assurance that they will earn back their transmission investments. The best and least expensive options are those that leverage low-cost public financing so as to maintain to the extent possible the Northwest’s relatively low electricity prices. Still, given the dire urgency of the climate crisis, all options are worth pursuing. Otherwise, Cascadians will be left holding the bag, coughing up for expensive and inefficient infrastructure projects while the planet burns.

BPA’s priorities: Low debt, low rates, few builds

BPA is, as Sightline has written about extensively, the Northwest’s transmission giant. And it looks flush with cash to pay for new wires: it has only tapped $5.7 billion of the $17.7 billion Congress authorizes it to borrow from the US Department of the Treasury.3

But BPA doesn’t see it that way. Understanding why requires looking back at the agency’s foundational statutes, which direct it to sell power from US government dams on the Columbia River to “public bodies and cooperatives” at “the lowest possible rates.” These “preference customers,” as they are known, include municipal utilities like Seattle City Light, public utility districts (PUDs) like Snohomish County PUD, consumer-owned cooperatives like Umatilla Electric Cooperative, and tribal utilities like Yakama Power. Just as these preference customers depend on BPA for power and transmission service, so too does BPA depend on them. US federal statute requires BPA to recover its costs, including debt repayment and interest, by selling power and transmission service; BPA does not receive annual Congressional appropriations. As of 2022, a full three-quarters of BPA’s operating revenue came from selling power, primarily to the agency’s preference customers.

In other words, if BPA were to reach further into its deep pockets to build a few multibillion-dollar transmission lines, it would need to pay back its federal loans by raising rates on its customers. And BPA has given no indication it is willing to do this. In fact, BPA’s 2022 financial plan emphasizes the opposite: maintaining low rates, reducing interest expenses, and lowering its debt-to-asset ratio. The agency’s financial challenges in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which included a precipitous drop in BPA’s cash reserves and concern that it would not be able to repay its US Treasury debt, likely contribute to the agency’s skittishness.

As a result, BPA places most of the financial risk for new transmission projects onto renewable developers that need BPA’s grid to zap power from solar and wind farms to homes and businesses across the Northwest. BPA’s requirements, including that developers post a security deposit or letter of credit to cover the cost of a transmission upgrade or new line until it is up and running, can be too high a hurdle for some developers to clear. And when no one wants to foot the bill, nothing gets built.

Then there is the contentious issue of whether BPA, to cover the cost of a new project, would raise its transmission rates only on the developer(s) that requested the additional grid capacity or on its entire customer base. Some, like the Northwest & Intermountain Power Producers Coalition (NIPPC), which represents the region’s independent renewable developers, argue that raising rates only on developers “can be a kiss of death” for their solar or wind projects. Plus, NIPPC contends, doing so ignores the broad benefits that new transmission provides to all BPA customers. Others disagree.

“Why should a public facility pay for a transmission upgrade that is designed to help one private entity provide power to another private entity?” asked Nicolas Garcia, policy director for the Washington Public Utility Districts Association (WPUDA), in a conversation with Sightline. He argues that since BPA’s preference customers already rely almost entirely on carbon-free electricity from BPA’s hydropower resources, they shouldn’t pay for grid upgrades, the purpose of which is to help IOUs clean up their power sources.

Still, appetite among BPA’s preference customers to see the agency invest in more transmission wires may be growing. Garcia acknowledges the need for more transmission capacity, especially across the Cascade mountain range. Lauren Tenney Denison, director of Market Policy & Grid Strategy at Portland-based Public Power Council (PPC), a membership group that includes BPA’s preference customers, echoed the sentiment. While traditionally raising transmission rates “has been a huge concern” for PPC’s members, she told Sightline, she sees interest growing in getting new projects built.

In sum, BPA is sitting on billions of dollars of federally financed debt. But despite enjoying the statutory authority to tap this money and construct new wires, BPA approaches this essential climate strategy with wariness and trepidation. And IOUs, which own most of the rest of the region’s grid, aren’t hankering to pay for new large lines, either.

IOUs make an easier buck on small, local projects than on regional transmission lines

IOUs only profit by investing in new infrastructure. In theory, then, building pricey transmission lines should look like a sweet deal to them. But in practice, most IOUs consider transmission lines, especially large regional ones, too risky for four main reasons:

A. Transmission lines take longer for IOUs to build and recoup costs on than other infrastructure projects.

While a new solar or wind farm might take around five years to get up and running, transmission projects can drag on for 10 or even 20 years, primarily due to lengthy siting and permitting processes.4 Idaho Power and PacifiCorp first proposed the Boardman to Hemingway line almost 20 years ago, and it still hasn’t broken ground.

“No certainty for 15 years is unacceptable for a utility business,” Mitch Colburn, vice president of Planning, Engineering, and Construction at Idaho Power, told Sightline. “Our shareholders don’t want us to take big risks.”

These delays matter because IOUs cannot recoup their investment in transmission lines through state-approved electricity rate increases until the line is “used and useful” to ratepayers. And if the utility ends up having to cancel a project before completing it, the company will have to eat any costs it already spent. Such was the case with Portland General Electric’s (PGE) Cascade Crossing transmission project, which would have carried power across the Cascade mountains, now a heavily congested route. After opposition from BPA, which argued that the line was unnecessary, PGE canceled the project in 2013 and lost the $50 million it had already spent.5 The utility has not proposed a major transmission line in the decade since.

B. IOUs worry that state regulators may not allow them to recover transmission project costs through higher rates.

Compounding the timing challenge is that IOUs do not know if state regulators will ultimately allow them to recoup their investments by raising retail rates.

“The limit is the willingness of state commissions to put more and more projects into rate base,” said Maury Galbraith, executive director of the Colorado Electric Transmission Authority (CETA). And building lines that cross multiple states adds to the challenge.

“Take a hypothetical transmission project to bring wind from Wyoming to Oregon,” Shaun Foster, transmission strategy manager at PGE, explained. “We could see a scenario where Wyoming regulators don’t allow that.”

Indeed, this dynamic already plays out in the Northwest. PacifiCorp has developed an agreement for how to allocate its transmission costs (and other costs) across the six states where it operates.6 Public utility commissions in all six states must agree to the terms, a process that is “neither clean nor easy,” according to Bob Jenks, executive director of the Oregon Citizens’ Utility Board (CUB), which is party to the agreement.

C. The sheer cost of transmission lines makes them hard for IOUs to finance.

That transmission lines are billion-dollar or multibillion-dollar projects further exacerbates the timing and regulatory uncertainty IOUs face.

“Most utilities don’t have the balance sheet to carry a $2 billion transmission line,” Foster said. Indeed, most IOUs in the Northwest have less than $5 billion in long-term debt on their books today; in that context, an additional, say, $1 billion in long-term debt—for a single project that may not pay itself back for at least 10 years—is usually too big a risk to take on.7

The major exception again is PacifiCorp, the utility giant owned by billionaire Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy. It already possesses one of the largest privately held transmission systems in the United States and is investing billions in new transmission projects across the western United States.

D. IOUs must compete for regional transmission lines, but they enjoy monopolies over local ones.

Finally, large regional transmission projects are unattractive to IOUs because of the different requirements that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) places on them compared with local transmission lines. Since 2011 FERC has required that utilities compete to build regional lines, but it allows them to maintain monopolies over wires in their own service territories. While FERC had intended this rule to spur competition at the regional level, in practice it simply encouraged utilities to forgo regional transmission projects altogether.

Instead, utilities focus on local transmission projects where there is “no competition to them and they can do anything they want,” explained David Pomerantz, executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute, a nonprofit utility watchdog. FERC is now considering re-granting utilities monopoly rights over regional projects, but many public interest groups argue that this would be a step in the wrong direction.8 9 An alternative approach could be for FERC to open up competition for local transmission projects.

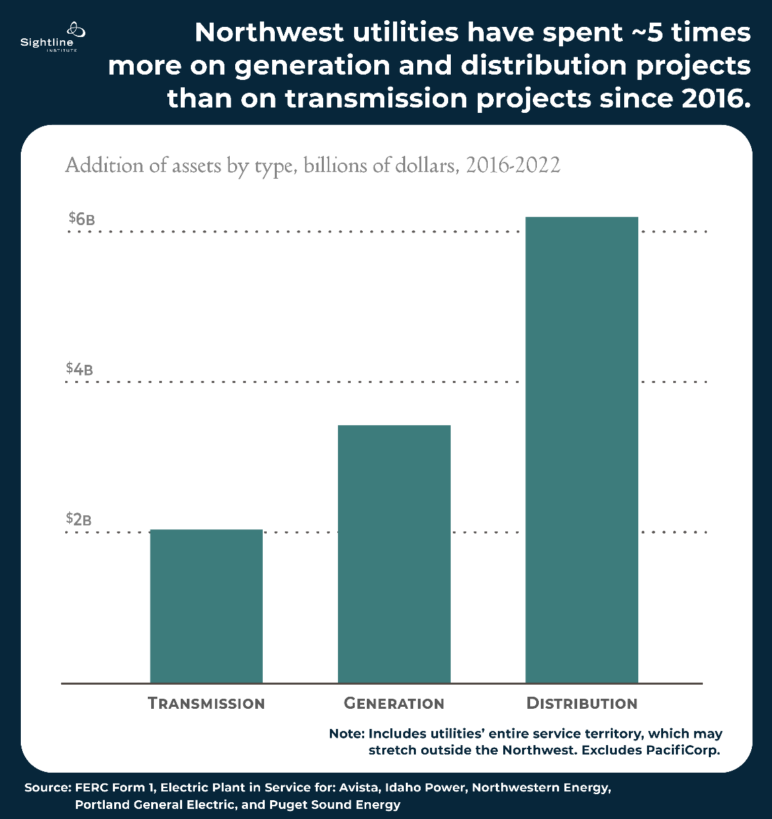

As a result of these compounding disincentives, IOUs spend chump change on regional transmission projects. The chart below shows that since 2016, Northwest IOUs have deployed nearly $10 billion in ratepayer money to new generation and distribution projects and just $2 billion to transmission ones.10 The vast majority of these transmission investments are for local projects; PacifiCorp and Idaho Power are the only IOUs in the Northwest proposing any regional transmission lines.11

Northwest leaders can help break the transmission funding deadlock

Northwest leaders, from state legislatures to the Northwest congressional delegation, all can play a role to unleash funds for new transmission lines. The best and least expensive options are those that leverage low-cost public financing, whether via BPA or a state-led entity (options 1 and 2 below). But, given the urgency of the climate crisis and the current transmission deadlock, all three strategies outlined below are worth pursuing together.

1. Washington senators Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray and the Northwest congressional delegation can encourage BPA to assume more low-cost debt.

The least expensive strategy would be for Northwest leaders to pressure BPA to use more of its federal borrowing authority (i.e., take on more debt) to proactively build new lines. Unlike an IOU, BPA has no profit motive, and it has access to some of the lowest-cost financing available. BPA’s weighted average interest rate for its federal debt was 3.1 percent, according to its 2022 annual report; that’s less than half the 7.23 percent that Puget Sound Energy, Washington’s largest IOU, reported as its weighted average cost of capital the same year. Plus, as the largest supplier of electricity in the Northwest, BPA could soften rate impacts by spreading the costs of large transmission projects over a wide swath of customers—something a single utility could not do.

But encouraging BPA to assume more debt will be no easy task given its stated financial priorities to do essentially the opposite. Changing those priorities will require leadership from the Northwest congressional delegation, which some observers regard as BPA’s informal de facto board of directors. Especially critical would be buy-in from Senator Maria Cantwell, who led the charge to increase BPA’s federal borrowing authority by $10 billion and recently applauded BPA’s decision to take steps toward $2 billion worth of transmission improvements.

2. The Oregon and Washington legislatures can create state entities to partner with non-utility transmission developers.

In parallel, Northwest legislators could establish state transmission entities with the ability to partner with non-utility transmission developers, following the lead of Colorado and New Mexico.12 These transmission developers, known as merchant developers, are far less risk-averse than BPA or IOUs are. That’s in part because they do not face the same heartburn as utilities do over recouping their project costs through state regulatory proceedings. Instead, merchant developers earn back their investments by selling transmission capacity to utilities or renewable developers, who in turn pass along the costs to ratepayers. But merchant developers’ risk tolerance comes at a premium.

“These developers really aren’t interested in the ratepayer impact,” said Galbraith of CETA. “What they want to lock in is a profit margin for their investors and shareholders.”

The potentially higher cost of merchant transmission lines might be mitigated, though, if a state entity partnered with them and opened the door to low-cost financing. Both Colorado and New Mexico’s transmission authorities can issue government-backed revenue bonds, which are, Galbraith explained, “if not the lowest cost capital, pretty close.” He is interested in arrangements with merchant developers that would require them to use some of this low-cost capital in exchange for the benefits of partnering with CETA, most of all its eminent domain authority.

By contrast, New Mexico Renewable Energy Transmission Authority (RETA) has not issued any bonds to help pay for the projects it has pursued with merchant developers. But that may be because its transmission lines export power; ratepayers outside New Mexico will bear the costs of the lines, likely lessening RETA’s concern with lowering project costs.

3. Governors Jay Inslee and Tina Kotek can lead a multistate cost allocation framework for regional transmission lines.

Finally, Northwest states could collaborate with utilities and BPA to agree on a way to allocate the costs and benefits of regional transmission projects. “If a regional body identifies a cost allocation framework, utilities have some semblance of assurance when they seek recovery at a state regulatory body,” said Foster of PGE.

Developing this type of agreement would, however, require a regional planning body, whether a regional transmission organization or some other entity. Today the Northwest sorely lacks this type of forum, as Sightline covered extensively in the first article in this series. Creating one would necessitate leadership from Northwest governors, likely beginning with those already committed to addressing the climate crisis. While NorthernGrid, the region’s current planning body, does technically have a cost allocation process and methodology, as FERC requires, it has never used it for any project, and state representatives have no influence over it.13

Jenks of the Oregon CUB agrees with Foster that a planning process that identifies how to allocate costs and benefits for necessary regional projects would likely increase the willingness of state utility commissions to allow IOUs to recover their transmission investments. However, he does not believe state regulators should preemptively approve IOUs’ potential transmission investments. Utilities can, he argues, “mismanage any project,” leading to potentially exorbitant costs for ratepayers. Plus, any transmission project that an IOU develops will inevitably be more expensive than a project that can leverage public financing, such as one BPA could build.

Some improvements could come when and if FERC finalizes a new rule it proposed in April 2022 that would require transmission planning entities, including NorthernGrid, to actively involve states in cost allocation processes. However, even if FERC finalizes this rule, BPA’s participation in any Northwest cost allocation framework would be entirely optional because the agency is not under FERC jurisdiction. As such, state leaders would still need to pursue a voluntary multistate, multiparty cost allocation agreement that includes BPA so as not to put all the financial burden for new regional transmission lines on IOU customers.

Not paying for more transmission capacity is the costliest choice of all

Transmission lines are expensive, but not building them is costing the Northwest dearly. As BPA and IOUs close their purses to regional transmission projects, our region is racking up an ever-worsening climate bill. In just the few weeks since Sightline published the first article in this series, hundreds of people in British Columbia and Washington lost their homes in devastating wildfires, Seattle’s air quality ranked the worst in the world, and Portland hit its highest August temperature on record and third hottest of all time. All the while, ratepayers are stuck paying billions for inefficient grid projects.

Northwest leaders, including Senator Maria Cantwell and Governor Jay Inslee, can break this logjam. They can lessen the impact on ratepayers with solutions that leverage low-cost public finance, though the climate crisis demands that all options be on the table. The question facing the Northwest is not whether we will pay, it’s what we will pay: the cost of a few more electric wires, or our health, livelihoods, and a livable planet.

Sightline fellow Laura Feinstein contributed research to this article.

Roger

What if more power could be generated locally? Where is the greatest population density in WA? Near the Sound. What do we have in the Sound that can generate electricity? Tides. Where is the tidal power? How big a snowpack does tidal power need to last through the summer? How long does the sun have to be up? What happens if the wind doesn’t blow for a week? What if we didn’t need so many transmission lines to move all the 100% reliable and predictable power long distances?

Tim Adams

Warming is a global problem and the northwest US has only a tiny bit of global population. While more lines are needed to allow more sharing of generation resources, the impact on the climate will be so small it won’t be measurable.