Micro-housing—dorm-room-sized apartments in desirable, walkable neighborhoods—isn’t for everyone, but it most definitely is for Anna Rogers. Anna is a recent college graduate who grew up in the suburbs of Seattle and now works a retail job while looking to start a career that harnesses her passion for politics.

Thanks to a building called OneOne6 on Seattle’s Capitol Hill, Anna can afford to live her twenty-something dream of her own private place—no sharing with Craigslist strangers or returning to her childhood bedroom at mom and dad’s. Capitol Hill is one of Cascadia’s most exciting neighborhoods, a thriving center of arts and nightlife, historic home to Seattle’s gay community, and now exorbitantly expensive.

Anna is hooked on the lifestyle: walking around Cal Anderson or Volunteer Park, meeting friends for coffee or happy hour, attending Pride events steps from her door, or frequenting the year-round farmer’s market. “Things pop up on Facebook, turns out they’re just two blocks away, and I can just swing by. I love that,” she says.

“My friends were like, ‘It’s too small; don’t do it.’ But I don’t feel that way. I have my own bathroom, a full bed, a desk, shelves…. I mostly just need a safe, clean place to shower, eat, and sleep…. There’s so much going on. I’m rarely home.”

Unfortunately for the many other Annas out there, eager to live close to good city jobs or to participate in city life, Seattle has now effectively outlawed micro-housing through the minutiae of policy and zoning rules. Seattle was the modern birthplace of micro-housing in North America. It went strong from 2009 to 2013, but building micro-housing projects has since become an uphill battle. In fact, the local war about micro-housing is over… and micro-housing lost.

This article is the story of that war—the obscure changes in land-use rules and departmental regulations that have now strangled a practical, modest, sustainable, unsubsidized form of inexpensive living that held enormous potential both for Seattle and for the rest of Cascadia. I’ve been involved in Seattle micro-housing as an architect and, more recently, a developer, since 2010. Building affordable homes and livable communities for people like Anna struggling for a foothold in our housing market has become a core mission of my practice.

But first, some terminology….

What is micro-housing?

Micro-housing is the umbrella term for a housing option that is smaller than average. These homes are the modern-day equivalents of rooming houses, boarding houses, dormitories, and single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels, and they come in two main flavors:

- Congregate housing is like a dormitory. The rooms are “sleeping rooms,” rather than complete dwelling units, and renters enjoy private bathrooms and kitchenettes in their units, along with shared kitchens and other common amenities for the whole building. A typical project looks like an apartment building—Yobi Apartments, near Seattle University, is one example. “Apodments,” the brand that started the micro-housing revolution in Seattle in 2009, are functionally the same thing as congregate housing, though technically they are classified as boarding houses. The size of the sleeping rooms in congregate micro-housing is typically in the range of 140 to 200 square feet.

- A Small Efficiency Dwelling Unit (SEDU) is a slightly undersized conventional studio apartment. It has a complete kitchen and bathroom and closet space. By code, SEDUs must have at least 220 square feet of total floor space, as compared to 300 square feet for the smallest typical conventional studio apartments.

All types of micro-housing unlock more affordable and small but independent homes for people who wants them. They are one more option to serve the broad spectrum of housing needs.

War of attrition

So what happened to Seattle’s micro-housing? There’s no one single moment when we lost the war. Rather, it’s been a process of accumulated bad decisions. In short, rule changes made by the city mandate larger and therefore costlier units, drastically limit the areas in which they can be built, require the extra process and expense of formal design review, and discourage participation in the city’s multi-family tax exemption, a program that lowers rents substantially for working-class households.

All types of micro-housing unlock a more affordable and small but independent home for someone who wants it.

The timeline below summarizes the series of misguided steps—most taking place just in the last two years—that have taken Seattle from micro-housing leader to micro-housing void:

2009: Micro-housing first appears on the Seattle market, near the University of Washington. Average home size is about 140 square feet.

July 2009: Seattle Times publishes an article about Videre Apartments, a proposed micro-housing building in the city’s Central District. Public awareness and NIMBY opposition grow.

2010-2013: Micro-housing proliferates and evolves. Average unit size increases to about 175 square feet, and production ramps up to more than 1,800 homes in 2013, nearly one-quarter of all new dwellings built in that year.

September 2013: New micro-housing legislation is proposed, requiring all projects to undergo design review and to include more amenities, like common areas and bike parking.

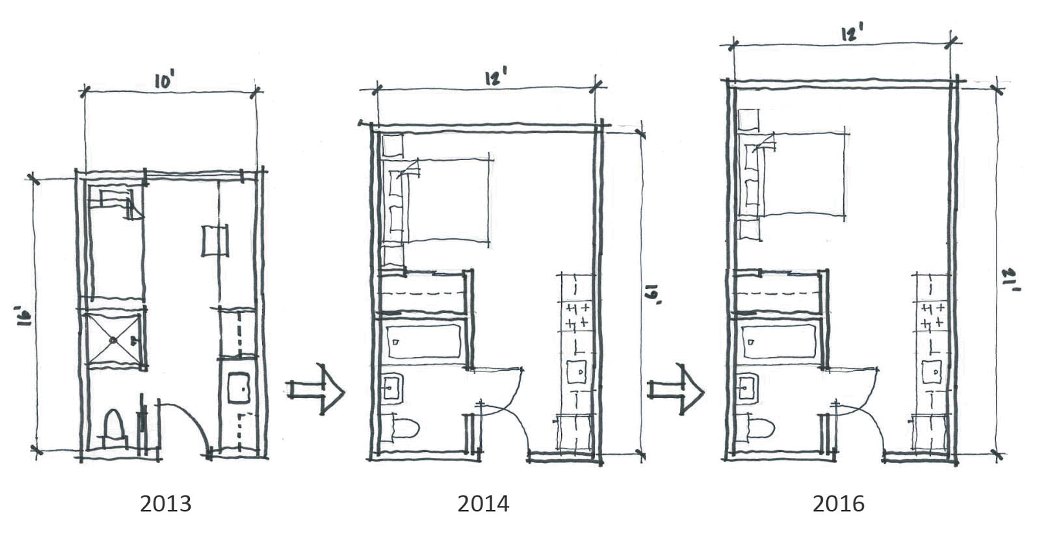

August 2014: King County Superior Court rules that all current pod-style micro-housing projects must go through the design review process, a time-consuming series of meetings with community members and a citizen panel that comment on plans. To avoid the expense, most existing projects switch over from pod-style to SEDUs.

September 2014: Revised micro-housing legislation proposes more expansive changes, including prohibiting congregate housing development in places zoned for neighborhood commercial centers and for low-rise multi-family buildings, such as small apartment buildings and duplexes. Such zones are exactly the parts of the city where most micro-housing was previously built and where it makes economic sense.

October 2014: Micro-housing legislation passes with some additional hostile amendments. Congregate housing is virtually banned and subsequently disappears from the development pipeline. SEDUs are encouraged as a replacement for congregate housing, with a minimum unit size of 220 square feet. However, other restrictions make this minimum size difficult to achieve, resulting in units averaging 250-270 square feet. Rents rise proportionally.

December 2014: A hearing examiner appeal invalidates the working definition of frequent transit, because the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections (SDCI) determines frequent transit based on average time between transit vehicle pickups. This change dramatically curtails the geographic extent of what the city can recognize as part of its “frequent transit network.” Proximity to the frequent transit network is the test for how much off-street parking housing developers must provide. Micro-housing construction cannot pencil out unless it is exempt from mandates to build off-street parking. Because of this change, micro-housing development is no longer cost-effective in portions of several of the city’s designated urban villages, exactly the transit-oriented density magnets where affordable options such as micro-housing are most needed. (The HALA committee flags this issue in early 2015 and again in its mid-2015 final report in recommendation Prk.3. The Seattle City Council could resolve this issue by adding the word “average” in one place in the land use code. To date, no City Council member has proposed this amendment.)

February 2015: The City Council passes changes to the multi-family tax exemption (MFTE), setting the rent restriction so low for SEDUs that participation in MFTE becomes improbable. (Since this time, only three SEDU projects have applied for participation in MFTE.) The rules also exclude congregate housing from participation, but then in Fall 2015, in response to HALA recommendation R4.b, congregate housing is allowed back in.

July 2015: The HALA report is published. HALA highlights the de facto ban on congregate micro-housing and recommends relaxing recently created restrictions to increase the supply of these homes. The Seattle City Council does not include this recommendation (MF.8) in its HALA work plan.

August 2015: SDCI adopts the “70-7” rule, a new interpretation of building code language that establishes the “minimum clear floor space” in a dwelling unit. The result is that the smallest and least expensive apartments in all of the micro-housing projects my firm has been working to build are suddenly illegal. (To date, the 70-7 rule remains unpublished in any public document. Builders usually discover the issue only when an SDCI inspector reviews a permit application and sends them a correction notice.)

October 2015: Based on Seattle mayor Ed Murray’s proposal, the City Council boosts the MFTE requirement for affordability from 20 percent to 25 percent of a multi-family building’s total units unless the building includes four or more two-bedroom apartments—not an option for micro-housing projects.

February 2016: My firm, Neiman Taber Architects, submits an appeal of the 70-7 rule for congregate residences to the Construction Code Advisory Board (CCAB). The firm argues that 70-7 is inconsistent with the published code interpretation manual, past practices, and historical models of small unit housing, and moreover, that it is counterproductive to the very habitability and livability concerns that it intends to support. The CCAB ruling upholds the 70-7 rule but acknowledges that the effect of the 70-7 rule on small unit housing and affordability should be studied. The CCAB asks SDCI to develop a code change to accommodate the design of small congregate units. (To date, SDCI has taken no action, but this issue is on the CCAB agenda for its Sept 15, 2016 meeting.)

June 2016: SDCI adopts new SEDU rules that apply the 70-7 rule to the entire living area of each dwelling. Many unit designs in the 250-280-square-foot range will no longer meet SEDU requirements, meaning they will have to be expanded into the size range of studio apartments. Regular studios, not micros, begin at 300 square feet.

August 2016: June’s new rules go from bad to worse, as the Director’s Rule on 70-7 is clarified to apply not only to SEDUs but to all new home construction in Seattle. The result? Even conventional studios will have to grow in size.

How does this succession of cuts impact projects?

The timeline is damning enough, but let’s look at the same story from another perspective—that of someone who is trying to build new housing for a few dozen Annas, without going bankrupt and with apartments that Anna can afford. Here’s a composite picture of a building project you might undertake.

You buy a plot of land in an urban village to develop micro-housing, anticipating its future residents will benefit from nearby frequent transit, grocery stores, a library and park, and some local shops. Your goal is to provide homes at affordable rents in a desirable neighborhood for the most people that you can. You’d also like to participate in the MFTE program, which gives you a property tax break that covers the cost of dramatically lowering the rent for a share of your tenants as long as those tenants have low incomes.

You draw up plans to build 40 apartments of 175 square feet each. You estimate rent at $900 per month. That amount might sound expensive if you haven’t shopped for rentals in Seattle recently, but it’s a steal: conventional studios now go for $1,400 on average.

Not so fast. Some of the folks who live nearby are upset about what you have planned. So the City Council passes new rules bumping up your units to an average of 220 square feet, and then, in committee, adds some more rules that jack your average unit size further.

You redesign your project according to the new rules and find that you are now down to 27 units of 260 square feet each. Thirteen Annas just lost their housing, and the remainder saw their rent rise by a third, to about $1,200 per month. But at least you are in the MFTE program, so five of your apartments will offer a discounted rent of $1,020 per month to people whose incomes qualify. (You facepalm in disbelief, however, that whereas your original plan offered 40 units, unsubsidized, at $900 a month, your new version has just five units, subsidized, at $1,020.)

Hold on just a second, though, because your Plan B just ran aground. The City Council has decided that the MFTE deal is too good for you, and it adopts more-demanding program requirements, dropping MFTE-discounted rents to $618 per month. Some quick math tells you your property tax break will not come close to covering the rent subsidy.

On top of this, the Mayor’s Office decides to promote family-sized housing by bumping up your MFTE participation quota: you have to subsidize rents for a quarter, not a fifth, of your tenants. You’re baffled why the Mayor’s Office thinks that driving you out of the MFTE program is helping to build family-sized housing. You give up on the MFTE program. There will be no discounted units. The Annas will all have to pay $1,200 a month. Maybe their parents will chip in?

Nice try. The building department is concerned that your apartments are so small that they might pose a threat to life, health, and safety. (You groan in frustration. The National Healthy Housing Standard was revised by an expert panel in 2014 to radically reduce the emphasis on minimum space as a health and safety concern. Previous editions of this model US building code had, based on little empirical evidence, recommended space quotas that criminalized the living conditions of many low-income families, but the new codes, based on a thorough review of the research literature, suggest a minimum of just 70 square feet per room and eliminated all other references to crowding. Sightline’s research informed this change.) The building department publishes a new code interpretation that requires your SEDUs to have larger living rooms. You redesign your project again: Plan C. Three more Annas lose their homes. You are now down to 24 apartments of 290 square feet that rent for about $1,300 per month.

At this point, you realize you’re better off converting the units into small, conventional studios. Your unit size bumps up again, to a little over 300 square feet—Plan D—but at least conventional studios can rationally participate in the MFTE program because the required rent subsidy is lower, so 25 percent of your tenants will get an affordable rent.

Not quite. The building department has a follow-up memo. It turns out that the living room size problem doesn’t just concern SEDUs; conventional studios are now also in danger of sliding below the purported minimum threshold for human habitation. This new interpretation applies to all housing, so your studios have to grow yet again. Your units jump up to an average of 330 square feet, Plan E. Three more Annas lose homes. Your unit count drops to 21. Your rents are now at $1,400 per month. They are not micros. Micros are dead.

This is how Seattle micro-housing regulations have evolved in less than two years. Spread over dozens of proposed small unit development projects, this represents the loss of hundreds of affordable dwellings and a huge increase in average rents. How much?

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline housing research right to your inbox.” form_title=”Housing Shortage Solutions Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

Seattle’s micro-housing “fix” costs the city 829 affordable homes per year

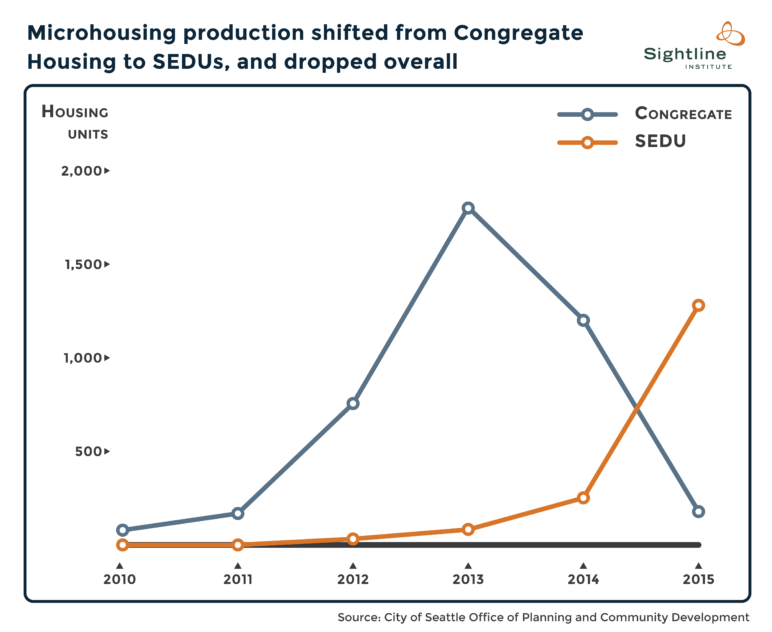

How many affordable homes is Seattle losing due to its new thicket of rules against micro-housing? The graph below illustrates how the production of congregate housing (including pod-style) and SEDUs changed between 2010 and 2015.

Congregate housing production, which peaked at over 1,800 units in 2013, was reduced to a trickle by 2015. SEDU production ramped up to fill the void but only partially—total micro-housing production is still 23 percent below its 2013 peak—and the rules keep forcing bigger SEDUs. This reduction in new supply exacerbates affordability by worsening Seattle’s housing shortage. On top of that, because they are larger and have more features, SEDU homes are much more expensive than congregate housing. It’s a lose-lose for affordability.

How much more are locals paying for what micro-housing does manage to get built under all new the restrictions? To come up with an estimate, I took 2013 as the base year and assumed that the total square footage of micro-housing built would remain constant over subsequent years. I then compared production for two scenarios:

- Under the current rules, 90 percent of total micro-housing production is SEDU, and 10 percent is congregate (which is roughly what has been observed since 2014); half of the congregate projects and twelve percent of the SEDU projects participate in the MFTE program (a rough estimate of behavior since the February 2015 MFTE rule changes).

- Recent anti-micro-housing policies are reversed. Production is split equally between congregate and SEDU; half of the congregate projects and half of the SEDU projects participate in the MFTE program (this also assumes that the MFTE limit for SEDUs is 55% of AMI).

Compared to scenario 2, for every year that Seattle’s current micro-housing policies remain in effect under scenario 1:

- Some 1,300 people pay an average of $253 more per month in rent, or $3,040 more per year. That’s just a little short of a year of in-state tuition at Seattle Central College. And that’s just the price increase that results from micros being larger than they would have been under the rules of 2013. The general rent increases that housing shortages cause add to it. Every rent increase and every home not built ultimately increases economic displacement of low-income people.

- Some 345 homes a year, market-rate and subsidized, are not built. Developers are building fewer, larger apartments.

- Some 97 congregate homes are not built that would have been affordable to Seattleites making 40 percent of area median income (AMI; $25,320 for a single person for 2016).

- Some 51 SEDU homes and 680 congregate units are not built that would have been affordable to Seattleites making 55 percent AMI ($34,650 for a single person in 2016).

Those numbers are bad enough. But now stretch them over ten years, and they represent the loss of 8,290 affordable homes, a 25 percent rent hike for 13,000 people, and 3,450 total homes—market-rate and affordable—never built at all.

What now?

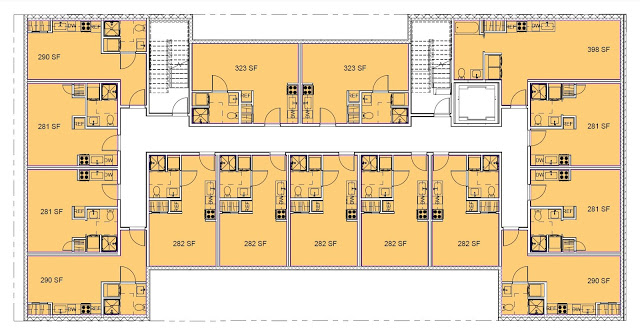

The last two years of compounding restrictions, with the final blow of the new 70-7 Director’s Rule, mean that virtually all proposed small unit projects will have to go back to the drawing board for a redesign to enlarge the units. An example of this change is shown below, where a project loses two homes per floor under the new rules. The unit count drops by about 10 percent, and the average unit size grows about 10 percent, with rents rising accordingly. Most SEDUs built from here on out will be virtually indistinguishable in density and unit size from today’s conventional studio apartments.

Before

After

In sum, barring future changes, micro-housing in Seattle is essentially done. There will be a few projects around the margins that will continue to keep the format alive in the technical sense. But in real terms, that is, in terms of providing an abundant, affordable alternative to conventional development, at a production scale where it can make a meaningful difference? Nope. Game over.

Anna was lucky to find a home that fit her needs, her price point, and her desire to live in one of Seattle’s most vibrant neighborhoods. Unfortunately, far fewer Annas will find that opportunity. Seattle has effectively mandated bigger, more expensive, and fewer homes—and turned its back on a smart, affordable housing option for thousands of its residents.

The only good news in this tragedy—this travesty of displacement and exclusion of low-income workers—is that we know exactly what to do to bring micro-housing roaring back. The only things that stand in its way in Seattle are a series of unforced errors that started in October of 2014 and culminated in the 70-7 rule. Remove them, and literally thousands of Annas will have the choice of new, small, inexpensive, unsubsidized, sustainable homes in walkable, transit-rich neighborhoods.

David Neiman is a principal at Neiman Taber Architects, where he is deeply involved in micro-housing as an architect, developer, and proponent in the public policy sphere. He served on the HALA committee. His firm works to create plentiful, high-quality, small unit housing, designed to support livability and promote community among residents. He coauthored a Sightline article on missing middle housing and design review for Sightline in February 2016.

This article is adapted from three articles published by Neiman Taber Architects. Sightline’s Serena Larkin, Alan Durning, and Dan Bertolet edited and adapted the pieces for Sightline.

Notes

The graph of micro-housing production counts each sleeping room in congregate housing as a separate housing unit.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline housing research right to your inbox.” form_title=”Housing Shortage Solutions Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.