Whatcom County, Washington, is a battleground in Cascadia’s fight to hold the Thin Green Line against fossil fuels. The fight against the Gateway Pacific coal export terminal also provides a window into how democracy is broken in North America—and how we can fix it.

“The fight against the Gateway Pacific coal export terminal also provides a window into how democracy is broken in North America—and how we can fix it.”

November’s ballot will offer Whatcom voters two options for changing their voting system: one that will make their Council far less representative of county voters, and one that will make it slightly more so. Voters will not have the option to approve proportional representation—a voting system that would guarantee the Council accurately mirrors the people.

The first option—I’ll call it the three-district option—would keep the current county district boundaries but switch from at-large elections to district voting for six out of seven seats. The second, five-district option would keep the county’s current voting system—district primaries and countywide voting in the general election—but would create five new districts in place of the current three. A switch to district voting with the three-district option could have profound implications for Whatcom and for coal exports, possibly enabling pro-coal conservatives to consistently win four out of seven council seats and give the green light to a huge new coal export terminal. But Whatcom’s choice offers larger lessons for voters across Cascadia about the risks of district-only voting.

District-only, winner-take-all-voting—when the person who wins the most votes in a district becomes the sole representative of all the voters in that district in that election—is a deal with the devil. It comes with immense downsides.

Districts are delicate

In a representative democracy, the legislature should be a mirror image of the voters. But winner-take-all, district-only voting creates a distorted kaleidoscope image. Whoever arranges the mirrors inside the kaleidoscope (draws the districts) largely determines what the image (the legislature, or council) will look like.

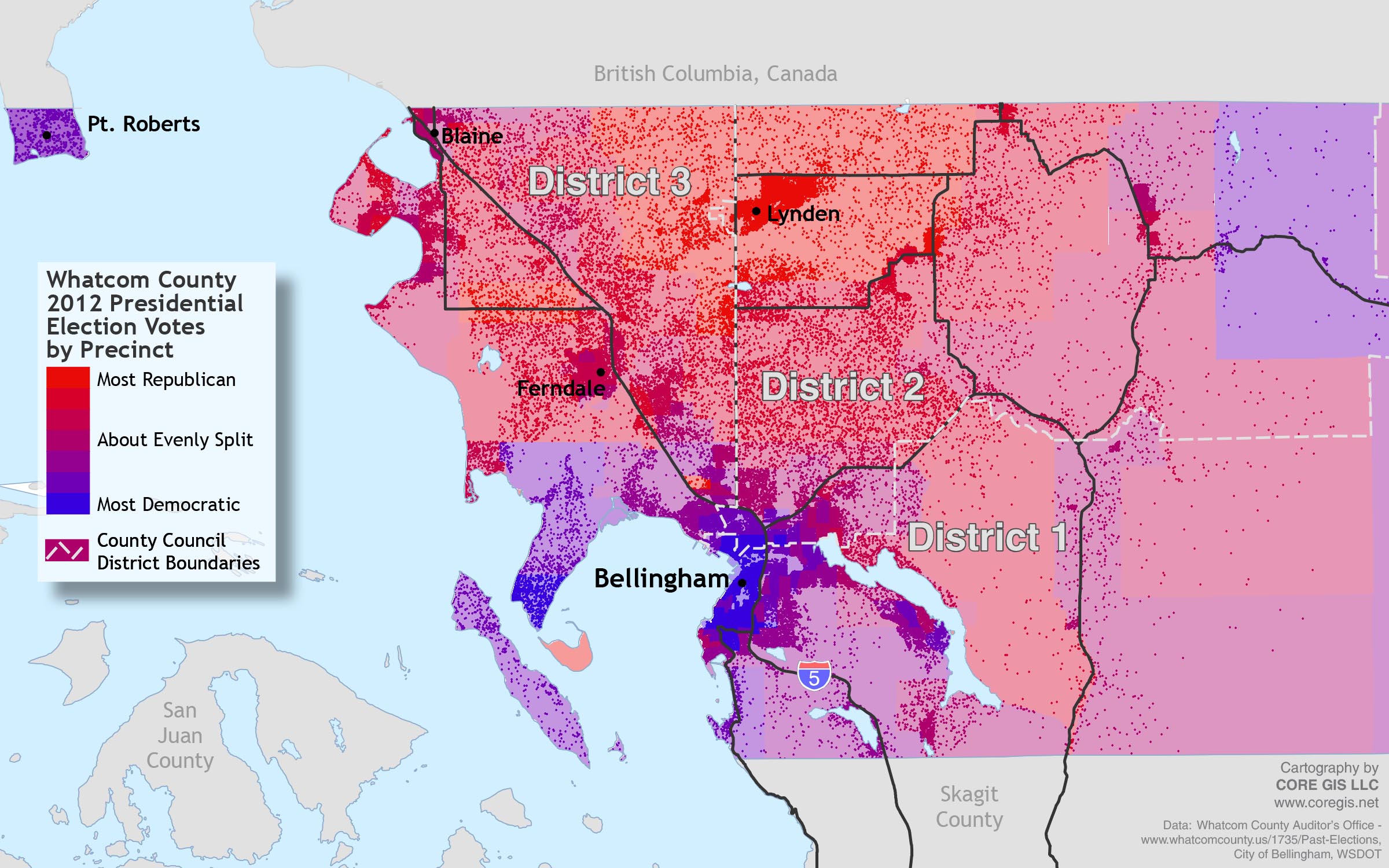

It is tempting to grab for the kaleidoscope if you think you can control the district boundaries. In Whatcom, the Republicans like the gerrymandered district lines that enclose most Democrats in District 1, making District 1 elections a landslide for Democrats but giving Republican voters, spread thinly across Districts 2 and 3, the opportunity to gain slim majorities in two out of three districts, despite being in the minority in the county as a whole.

The three-district map below shows a picture that is repeated across the United States: most Democratic voters (blue dots) are packed into the urban center, while Republican voters (red dots) are spread across rural areas. Proportional districtwide voting would mean the council would look much like the map—split between rural Republicans and urban Democrats, and leaning slightly more towards the latter, as voters do. Because the current districts divide the many urban voters between three districts and concentrate the less numerous rural voters in two districts, district-only voting could enable Republicans to win a disproportionate number of seats.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

But beware: district voting systems are sensitive. Small changes in district boundaries or voter demographics—tiny movements of the kaleidoscope—can lead to a completely different image.

For example, conservatives are counting on winning both seats in Districts 2 and 3 with district-only voting, since those districts generally vote majority Republican in odd year elections. However, in the high turnout election of 2012, District 3 voted 53 percent for Obama, and even District 2 went 48 percent for Obama. A high turnout election, or a deviation in demographics leading to a two to three percentage point shift in voting in District 3 and a three to four percent shift in District 2 could tip the council composition from the conservative hope of three Democrats and four Republicans to the conservative nightmare of seven Democrats and no Republicans.

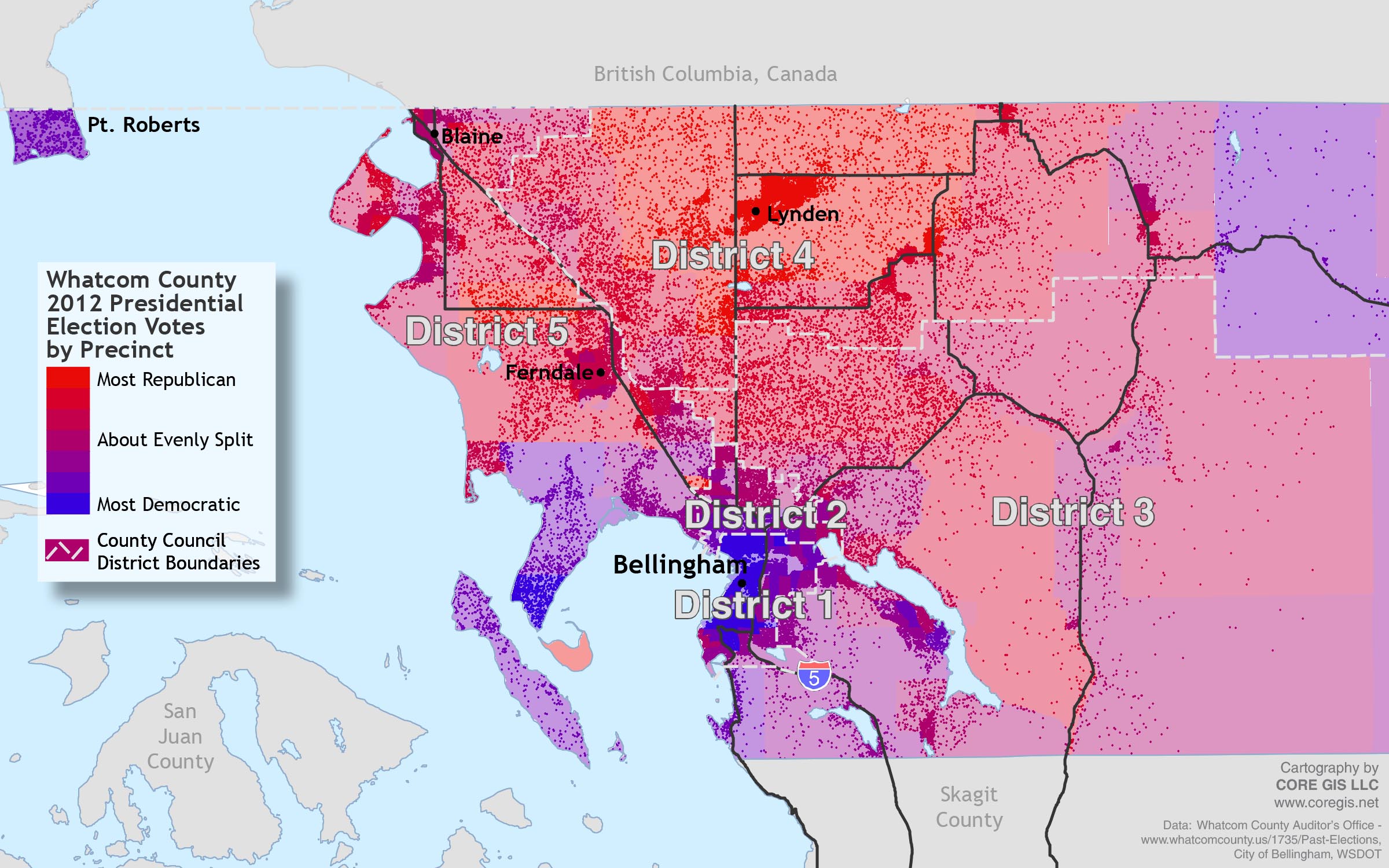

The five-district option would draw district boundaries around more cohesive communities—keeping more urban voters together and more rural voters together. The map below is a rough approximation of where the boundaries might be drawn, based on the ballot language. By giving all voters the opportunity to vote for all seats in the general election, the five-district option does not allow the kaleidoscope to go haywire, as it could with district-only voting.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Proportional representation—an option that the conservatives on the Charter Review Commission prevented Whatcom County voters from voting on in November—does one better and creates a faithful mirror image. You always know exactly what kind of council you will get. One that looks like voters. Gerrymandering is impossible.

District-only voting promotes parochialism and gridlock

Not only is the kaleidoscope district-only image temperamental and sensitive to tiny changes, it is also fractured. County Councilman Rud Browne, testifying against district-only voting to the County Charter Review Commission, asked, “Why would you want to give up your right to vote for every member of the County Council? Why would you want to bring Congressional stagnation to Whatcom County?” Browne is correct that winner-take-all, district-only voting is one of the root causes of the United States’ partisan, polarized, gridlocked Congress.

“If most councilors only answer to narrow geographic interests, the council will make worse decisions about issues of county-wide interest.”

Whatcom voters saw the dangers of parochialism when they tried, and promptly rejected, district-only voting in 2007. Voters quickly realized, to their dismay, that if you only get to vote for three councilors, the other four don’t care what you think. When voters discovered that the Charter Review Commission planned to put another district voting amendment on the November ballot, they came to the Commission’s June 8 meeting to testify against district voting. Whatcom business person Jeff Margolis told the Commission: “We don’t want parochialism. We want all councilors to be dedicated to the whole county.”

Long-time resident Dennis Smith gave a specific example of how parochial infighting can play out: in the 1980s, he said, the county was looking for a site for a landfill and picked a clearly inferior location because councilors were looking out for their own turf, rather than the greater good.

Whatcom resident Jeremy Standen said, “When we vote for council, we should be thinking of the county as a whole,” and other people pointed out that the county is a special, interconnected place.

District-only voting creates sustainability and governance challenges. If most councilors only answer to narrow geographic interests, the council will make worse decisions about issues of countywide interest such as coal terminals, landfills, and water regulations. County-wide voting ensures the council considers the county as a whole. Proportional representation would ensure the council always represents all the people of Whatcom.

District-only voting would leave many voters without a representative they voted for

The power of district boundaries is not a fluke. Even nonpartisan redistricting will not prevent the distortions it induces. It is part of the DNA of winner-take-all district-only voting. With district-only voting, 51 percent of the voters in a district elect a representative and the other 49 percent elect no one.

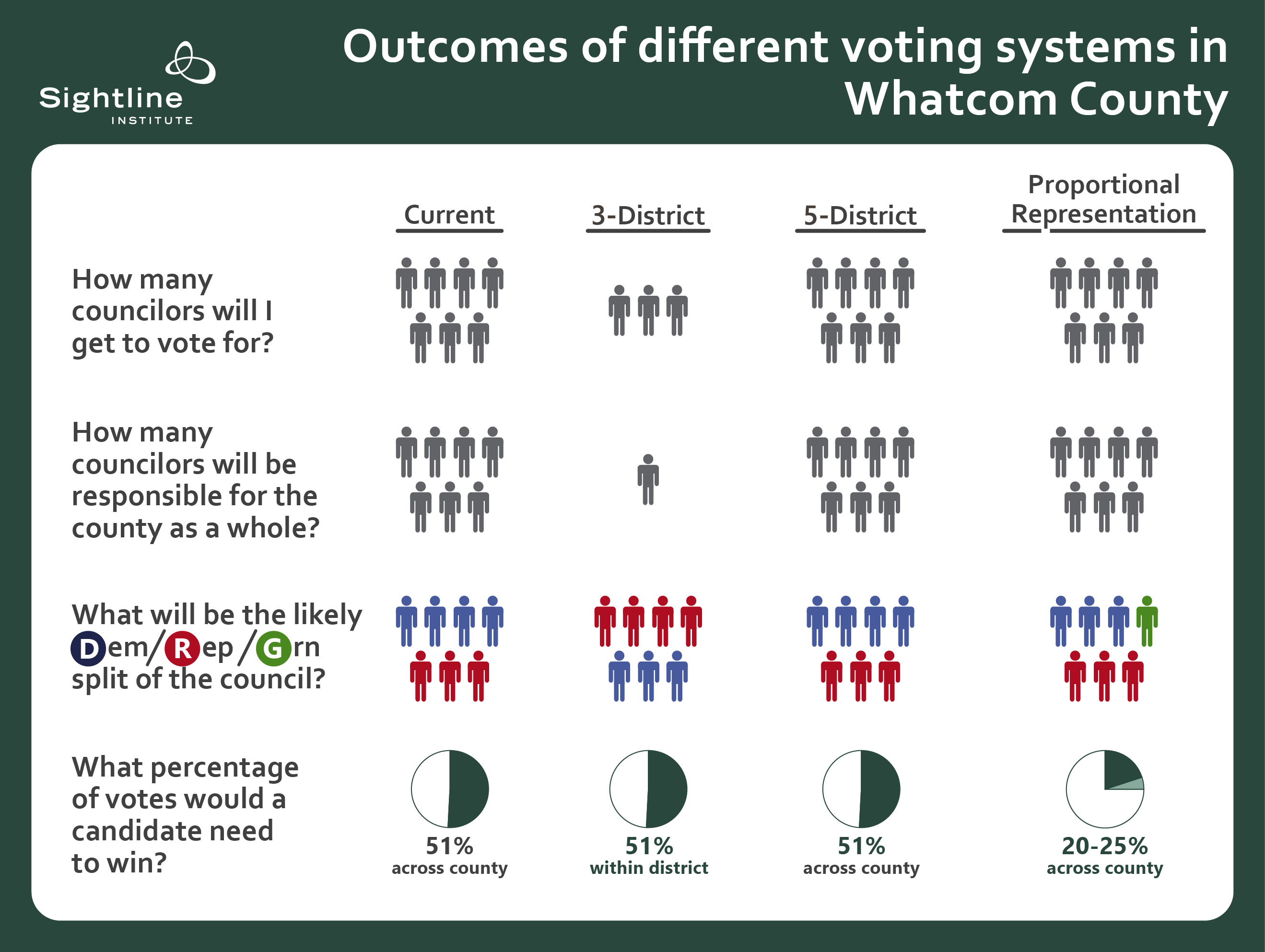

Cascadians want more opportunity to elect a representative they support. Many Whatcom residents testifying at the June 8 meeting echoed what Whatcom nurse Maureen Cleveland said: “I want the right to vote for all the councilors.” Voters want seven chances to elect a candidate, rather than only three. The current system and the five-district option give voters seven votes. But ranking all your choices—rather than voting for just one for each seat—gives you even better odds. With proportional representation, any group of like-minded voters making up about 20 to 25 percent of the voters could elect a council member.

For example, people who live in rural towns such as Lynden, Blaine, and Ferndale make up about 16 percent of Whatcom voters. If they banded together with enough like-minded rural voters to get to 20 or 25 percent, under proportional representation, they could elect a candidate who speaks primarily for their interests. None of the other voting systems gives rural voters that option.

Third parties might also be able to muster 20 or 25 percent support and elect a representative under proportional representation. For example, Green Party candidate Bob Burr got 26 percent of the vote in his bid for a City of Bellingham Council seat. True, he would get less of the vote in a countywide election, but he might get a bump if voters knew that, under proportional representation ranked-choice voting, they can rank their favorite Green party candidate without fear of spoiling the election for their favorite Democratic candidate. Here’s how that might look:

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Under winner-take-all voting, including Whatcom’s current system and the five-District proposal, receiving 25 percent of the vote is never enough to win. Under proportional representation voting, a third-party candidate with that much support would claim a seat.

The kaleidoscopic machinations of winner-take-all district voting would leave many Whatcom voters unable to elect a representative. Proportional representation ensures that almost every single voter will have cast a ballot for at least one winner. The council will always reflect voters’ views, no matter how district boundaries are drawn. Liberal and conservative people, rural and urban dwellers would all have representation on the council in proportion to how many of them vote.

Different voting systems would have profoundly different outcomes for Whatcom County’s future.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

What’s a thoughtful voter to do?

Voters concerned with Whatcom County as a whole would do well to oppose the three-district option and support the five-district option. District-only voting could lead to a council that does not accurately represent the people, possibly leading to approval of a massive new coal terminal despite widespread opposition. Other important sustainability and governance issues will arise after the coal terminal, and a mostly district-only council crippled by parochialism and partisanship might not respond well.

“Proportional representation would ensure the council always represent all the people of Whatcom.”

Beyond this election, there are important questions for voters across Cascadia to confront: do our voting systems reflect the power of the people, or the power of gerrymandering? Do our elected officials represent all voters, or only a plurality?

Proportional representation would make district boundaries immaterial. County councils and other legislative bodies would always look like the people because any group of like-minded people, no matter where they live within the county or state, could band together to elect a councilor or representative of their choice.

Thoughtful voters in Whatcom could look for opportunities to put proportional representation on the ballot in a future year. Voters across Cascadia can look for opportunities to promote proportional representation in their own communities.

Jay Taber

The Whatcom Tea Party has gotten off lightly, considering it’s leaders operate the PACs funded by GPT, and use their KGMI radio programs to promote anti-Indian racism and violence. Check out the following timeline.

http://publicgood.org/pdf/gatewaypacific-terminal-timeline.pdf

Weezy

This paean to representative democracy hits the usual notes: empowerment of people, dis-empowerment of special interests, local government managers listening and acting to further the interests of households not the fossil fuel profiteers, etc.

Isn’t this all backward-thinking, and at odds with the shining Grand Experiment in municipal governance that by all accounts is the greatest thing this state is offering by way of example to the country? Whatcom County’s proposed changes to “by-district” voting in fact cut against the modernist trend in Seattle-area politics. Allow me to offer a modest proposal. We’ve been on the right track for twenty years now – appointive legislative bodies – and we should be putting more of our eggs into that basket.

Why should the legislative body of that county even be elected? The crowing glory here is Sound Transit, and people can’t use any political means to control who adopts the legislation for that municipality.

The Seattle Popular Monorail Authority had an appointive board as well, and Sound Transit’s appointive board supposedly is the wave of our progressive future.

Why not just let the governor appoint all of the county’s councilmembers? That would be better in our fast-paced modern world. The King County Executive already appoints more than half of Sound Transit’s boardmembers. Why shouldn’t the governor be the appointer for county councils?

Everybody reading Sightline thinks Sound Transit’s appointive-board structure is beyond excellent. Nobody in the state’s power structure thinks Sound Transit’s board should be directly-elected. The oligarchy is a streamlined and efficient model of governance.