This fall, British Columbians will decide whether to switch to some form of proportional representation. It will be the third such referendum since 2005. This class of voting systems, locally known as ProRep or PR BC, better matches the share of a party’s seats with the amount of support it gets from voters. Some would say ProRep is overdue. Ten of the last twelve governments did not have support from majorities of voters, which is a situation that ProRep can remedy. Will it win this third time? It depends on whether the major parties expect third-party voting, now at its highest level since 1991, to last into future elections. In theory, that could give the two dominant BC parties—the ruling New Democratic Party (NDP) and the formerly-ruling Liberal Party—an incentive to join other groups in supporting reform. In practice, the NDP is backing reform while the BC Liberals have come out strong against ProRep. Each party’s stance can be explained by its relationship to minor parties, and corroborated by the history of electoral reform in BC.

Third-party voting comes before the change to ProRep

There are two main ways to get ProRep. One is for politicians to enact it within government. A second is for the people to vote it in themselves. But even when the people appear to be in charge, such as during a referendum process, subtle messages from their parties can determine how they vote. In 2009, for example, the ruling Liberal Party worded the referendum question as a choice between “the existing electoral system” and ProRep. This likely led Liberal voters to conflate reform with an attack on their party’s majority.

Major parties typically support ProRep when they believe it will help them win elections. The BC Liberals first proposed ProRep in the wake of the 1996 election. Despite the Liberals getting more votes, the New Democratic Party won control of the Legislative Assembly. In response to this “wrong-winner” election, the Liberals promised election reforms if voters would return them to power in 2001.

But when parties begin to win again, they often change their tune. Liberal leaders gained the seat majority in 2001 and, confident in their ability to continue winning under First-Past-The-Post (FPTP), they backed away from their party’s earlier reform posture. As the 2005 referendum approached, the party’s legislative majority imposed a hard-to-meet win threshold: 60 percent of votes across the province, and 50 percent of votes in each of 60 percent of electoral districts. (58 percent of voters supported reform.) Four years later, in 2009, the Liberal Party opposed ProRep outright.

In 2017, third-party voting was again on the rise in BC. The Green Party won 17 percent of votes, which is roughly twice its share in each of the previous three elections. Current polls have that holding fast. Although the Conservative Party did not win any seats, polls suggest it has voter support in the low teens.

Dominant parties seek change when they fear vote-splitting

For a major party to support BC PR, it needs to believe that some third party will split its vote in otherwise winnable districts. Consider the incentives of the NDP, now in the best position to make or break electoral reform. If Green support is strong enough to split the NDP vote in some districts, the NDP might lose those ridings to Liberal candidates. Votes for losing NDP candidates get “wasted”—they can’t help elect a party’s deputies. A ProRep system, by contrast, adds votes up over larger areas and helps elect a party-proportional share of candidates in multi-seat districts.

Another option, theoretically speaking, would be for the BC NDP to pack Green voters into a small set of single-seat districts. In practice, the party cannot draw lines in its favor because Canadian ridings are all drawn by independent commissions. But in any case, it would be hard to do because Green and NDP voters are mixed together. In the 2017 election, in 17 of the 43 districts won by Liberals, the Green candidate’s vote-share was large enough to prevent an NDP win (assuming those Green voters otherwise would have voted NDP). The average NDP vote in those districts was 35 percent, plus or minus 5 points. In districts won by Liberal candidates where the Green Party was not strong enough to have been a spoiler, the average NDP vote was 28 percent, plus or minus 4 points. The NDP does better where the Greens also may be a problem for it.

The Liberals don’t currently have a vote-splitting problem on the right. The minor-party to their right, the Conservative Party, didn’t win any seats in the most recent election. (Non-Canadian readers may be confused by the fact that the BC Liberal Party is center-right and unrelated to the center-left federal Liberal Party of Prime Minister Trudeau.) And there were only two ridings where Conservative candidates got enough votes to conceivably split votes with the Liberals and therefore help the NDP win. It appears the BC Liberals think they can win a majority without reform because the left is more fractured—between NDP and greens—than the right.

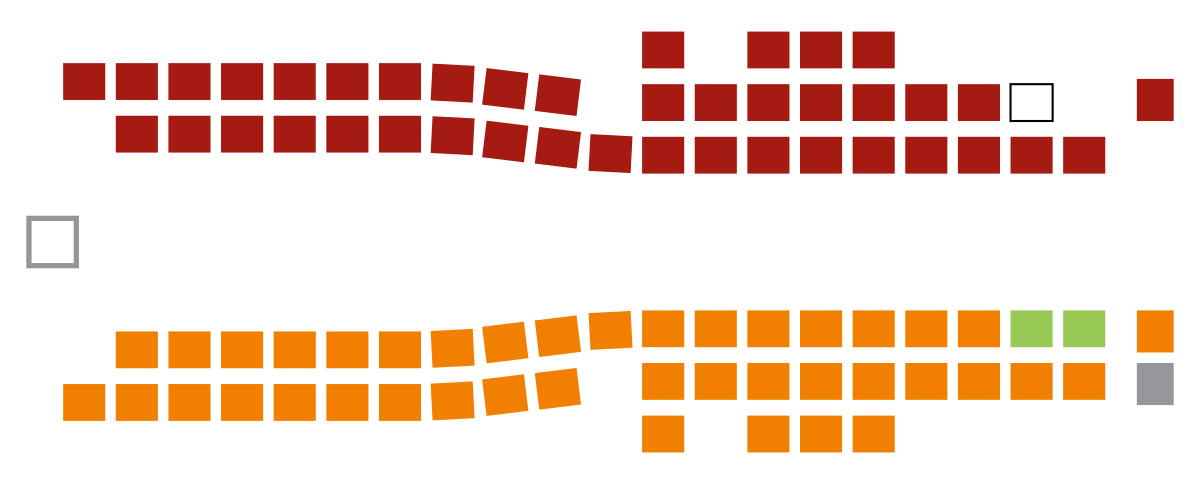

Composition of the 41st Parliament of British Columbia. There are 42 members from the BC Liberals, 41 from the BC New Democratic Party (NDP), three from the BC Green Party and one Independent. By DrRandomFactor – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Earlier BC reform efforts have succeeded when multiple parties were present

British Columbians have flirted with electoral reform for more than a century. Success has tended to happen when the number of parties was high.

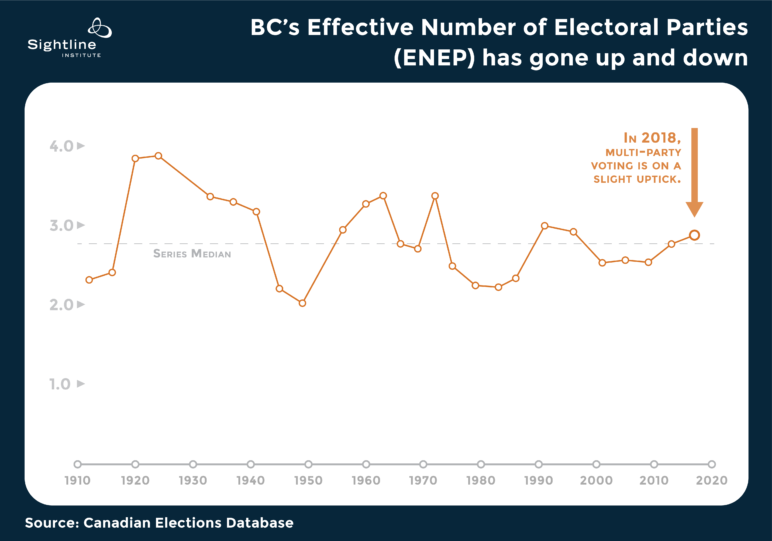

One way to measure multi-party competition is with the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP). This common political science measure is a size-adjusted count of a country’s (or province’s) political parties. Say there are two parties, and each gets 50 percent of the vote. ENEP in that case equals two. If one party does better, ENEP is less than two. If three parties divide votes evenly, ENEP equals three. At the national level, ENEP in Canada is 3.3, with the Liberals and Conservatives getting about two-thirds of votes and smaller parties dividing the remainder. ENEP in the 2016 US House of Representatives elections was 2.1, which reflects the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties.

According to one study, which looked at 37 cases of reform from the late 19th Century through 2005, the average ENEP in advance of a ProRep adoption was 3.9, plus or minus 1.6. Electoral reform, in other words, tends to succeed when multi-party politics are already in place.

The figure below plots ENEP for BC elections since just before World War I. Both of the most recent reform efforts, in 2005 and 2009, followed an uptick in multi-party voting, which began in 1991. By the time those efforts made it to the ballot, support for multi-party voting already died down.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Working our way back from the present, ENEP also spiked in 1972. Following that election, one of the two dominant parties, the Social Credit Party, lost and promised reform if returned to power. Elections in 1975 did bring the SoCreds back into power, but multi-party voting tanked, and the SoCreds backed away from reform.

Multi-party voting also spiked in the 1950s, when the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) threatened the two major parties: Liberal and Progressive Conservative (PC). In a bid to prevent CCF gains, Liberal and PC legislators agreed to switch to the Alternative Vote, a limited form of ranked-choice voting. The idea was to shut the CCF out of power by letting votes for Liberals transfer to PCs and vice versa. In the first Alternative Vote election in 1952, however, many transfers from the CCF helped bring the SoCreds into power. The SoCreds forced a new election, won a seat majority, and repealed the Alternative Vote.

The earlier two reform efforts did not involve ProRep. In the one that came to pass in 1951, establishment parties supported the alternative vote because they preferred each other to the CCF. The two dominant parties aligned better with each other than with the third-party CCF, their common enemy. Today, the two dominant parties (BC NDP and BC LIberals) are more opposed to each other, and both are open to working with the third-party Greens. When BC’s parties were forming the current government the Liberals and New Democrats each approached the Greens about a coalition deal. This new openness to multi-party government partly explains why ProRep is attractive to voters, the NDP, and the Greens. The Liberals are taking their chances that doubling down on a two-party system will benefit them, as it has since the right united and the left began to fracture after the 1996 provincial election.

What can we say about the ENEP spike in the early 20th century? As it turns out, this spate of multi-party voting coincided with the spread of ProRep systems in BC and Western Canada.

The Progressive Era spread of ProRep in Western Canada

Between the start of World War I and middle of the Great Depression, 20 municipalities in Western Canada switched to ProRep voting. Eight in BC used that system, thanks to provincial authorization in 1917: West Vancouver, Port Coquitlam, New Westminster, Nelson, Mission, Victoria, Vancouver and South Vancouver, a city later absorbed into Vancouver. As our ENEP chart above shows, these adoptions coincided with a period of multi-party voting that came just after World War I.

Third-party entry was gaining steam in other provinces too. In 1921, a new Progressive Party won the second-most votes nationwide in Canada. This performance was especially strong in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, where Progressives won more votes than any other party. Twelve more cities in these provinces went on to use ProRep, beginning with Calgary in 1916.

Canadian cities with ProRep used a form known as the single transferable vote (STV). With STV, voters rank candidates instead of choosing among parties. One of this year’s reform options, Rural-Urban ProRep, incorporates STV. Two other options also have candidate-based features.

Why did early reformers turn to STV? The short answer is that third-party voters were reluctant to unite behind a single, minor party. The sizes and identities of their parties were unclear, and reformers couldn’t easily project how party-based ProRep would affect the balance of power. Instead, lowering barriers for individual candidates was an easy point of agreement.

Reluctance to form a single party was rooted in class divisions in the Canadian Progressive movement, especially in the years around the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, and “sympathy” actions in other cities. Strikes like these tended to splinter Progressives into left- and right-wing factions.

The absence of a single, strong third party also affected the way that ProRep was adopted. In Western Europe and other countries, the typical adoption had an incumbent government reforming itself. This was to stop the advancement of some left-wing party and to deal with vote-splitting in single-seat districts. Canada’s diverse reform movement never posed a united threat to incumbent legislators. It was, however, able to force ProRep in major cities.

Why the cities abandoned ProRep remains a matter of debate. According to one argument, ProRep lasted only as long as organized labor was strong enough to fight repeal efforts. Another argument is that the STV counting procedure was too labor-intensive, especially given the hand counts needed a century ago. Voters’ difficulty understanding STV may have made it easy to attack the system, but that begs the question of what would motivate attacks in the first place. One possibility is that, due to shortages of candidates in some cities, STV simply wasn’t needed.

Another possibility is that the pro-reform coalitions, split as they were between left and right wings, ran into fatal disagreements. It may be that such candidate-centered ProRep systems are not stable without the features of normal, multi-party politics: formal candidate recruitment processes, party labels that simplify voting, and designated leaders who can manage internal disputes. Note that many of these party-like functions were weak, at best, in the Progressive movement.

Will BC reform elections in the 21st century?

When BC votes on ProRep in the fall, the Greens and their supporters will get behind the change. Their vote share stands 14 points above their share of seats in the Legislative Assembly. Conservatives may even get on board, as some polls put their party now at double-digit support, without legislative presence.

But to win, ProRep requires backing from at least one of the major parties, and the record here is clear. Such parties tend to support reform when they see it as a way to power. That, in turn, depends upon sustained threat from a third party.

Consider the BC Liberals. In 1996, they won 42 percent of votes and 33 percent of seats in a barely-three-party election that enthroned the runner-up New Democrats. Once Liberals returned to power in 2001 they launched the Citizens Assembly process, meant to discuss some form of ProRep. While those discussions were going on, third-party voting evaporated and with it the Liberals’ need for electoral reform. They followed through with their promise to put reform to a vote of the people but ripped the rug from underneath the effort with a 60 percent threshold to win.

Now it is the BC New Democrats’ turn. Without a seat majority, their current government depends on Green support. One condition of that support is this fall’s ProRep referendum. The NDP is supporting reform, but is it superficial? Time will tell, but one thing is certain from last year’s election: not since 1991 has voting behavior in BC been so clearly multi-party. Whether the NDP supports ProRep will depend on its assessment of the Green Party’s strength.

But note: fans of ProRep should not give up on the BC Liberal Party over the long term, even though the party’s near-term self-interest has made it the major opponent of reform. From 2001 until last year, the Liberals enjoyed a comfortable legislative majority. That lead shrank to just one seat. If third-party voting is responsible for that, or if Liberals again begin to feel, as they did in the late 1990s, that FPTP is working against them, a proportional system could be in the Liberals’ interest too.

Richard Lung

Unlike the impression fostered by the party-deferential media, elections are for electors, not for parties. In a democracy, voters don’t have to vote for parties at all. The BC Citizens Assembly recognised that the voters, and not the parties, are sovereign in an election. In practise that means the single transferable vote of voters lists, not party lists, to detrmine the personnel of parliament, under a proportional count.

Parties generally fight for dominance in the electoral system. All three options, in the third BC referendum, insist on the presence of party lists, mutilating (with the rejected MMP system) the democratic PR recommendation of the BC CA, in the process. But a free run is given to the MMP option, itself, the worst electoral system in the world for electors. (MMP is a doubly safe seat system of dual candidature.)

(Editor:)

John Stuart Mill: Proportional Representation is Personal Representation.

The Angels Weep: H. G. Wells on Electoral Reform.

(Richard Lung:)

Peace-making Power-sharing;

Scientific Method of Elections.

Science is Ethics as Electics.

FAB STV: Four Averages Binomial Single Transferable Vote.

(in French) Modele Scientifique du Proces Electoral.