A few years back, coal exports were a hot topic up and down the Northwest coast. The coal industry had proposed no fewer than nine export projects from Oakland, California, through Vancouver, British Columbia, all designed to ship coal to Asia.

One by one, each proposal died, falling victim to a potent cocktail of political opposition and dismal economics. And the economics were really, truly terrible. By 2015, a multi-year collapse in Pacific Rim coal prices had turned West Coast coal exports into the financial equivalent of a no-fly zone.

Yet some of the more desperate segments of the coal industry have kept their West Coast coal export fantasies alive. And they now have the ear of President Donald Trump’s administration—which, having failed to secure a massive bailout for domestic coal power plants, promptly floated the absurd idea of using US military bases as coal export terminals. Federal officials also ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to restart federal permitting for a coal export project that had already been blocked by Washington State.

Even well-positioned coal companies are struggling to make money from exports.

Some of the renewed fervor for Asian coal exports likely can be traced to a handful of hucksters, including a private equity group registered in the Cayman Islands that made big bets on selling coal to Asia half a decade ago. The firm still hopes to rescue those failed bets, and its underlings now pound the pavement in Washington DC and in state houses in the western US, shilling for an idea that prudent investors abandoned long ago.

This excellent opinion piece over at Bloomberg helps explain why would-be coal exporters have focused their attention on Washington rather than Wall Street: the economics of West Coast coal exports stink. Exporting coal to Asia—wresting the mineral from the ground, hauling it more than 1,200 miles by rail to coastal ports, unloading it at a terminal, reloading it onto a cargo ship, and then shipping it thousands of miles across the ocean—typically costs more than Asian buyers are willing to pay. The mammoth coal mines at the southern end of Wyoming’s Powder River Basin (PRB) face particularly poor prospects in export markets, due to the long distances their low-energy coal must travel.

Even well-positioned coal companies are struggling to make money from exports. Take Cloud Peak Energy. The company’s Spring Creek operation has the best export position of any PRB mine, with a comparatively short rail trip to the coast, plus a slightly higher energy content that earns a modest premium in Asia.

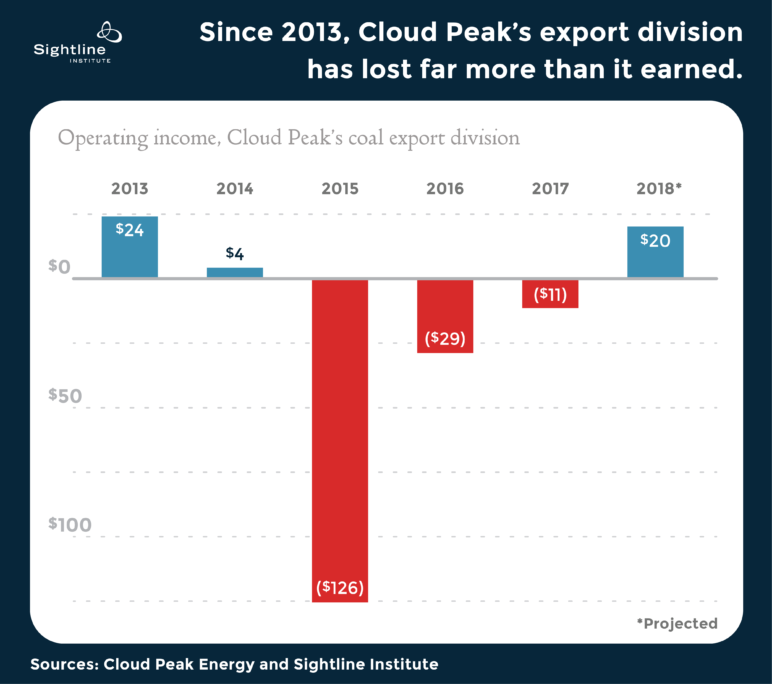

Despite these export advantages, Cloud Peak’s export arm still spilled a torrent of red ink over the past few years.

The worst years were 2015 and 2016, when Asian coal prices hit rock bottom and Cloud Peak paid huge penalties to back out of its export commitments. For a few quarters in 2016, the company halted export shipments entirely—while still paying contractual penalties for not shipping coal.

Cloud Peak did manage to squeeze out some export profits over the past year after Pacific Rim coal prices rebounded. Yet its export business remains fragile, vulnerable to every twist in the volatile seaborne coal market. In fact, the company’s CEO recently admitted that export margins will dry up next quarter due to a sustained decline in Asian prices.

And remember, this is the record for the company with the best export position of any PRB coal producer. For other PRB coal companies—ones with higher mining costs, or lower-energy coal, or longer rail distances—the red ink would have been far worse.

To be sure, the communities in the Northwest will need to remain watchful of the coal industry’s export fantasies. But they’ll always have a powerful weapon in that fight: the reality that coal exports remain a risky business.

Michael Mathews

Have you taken into consideration Coal technology? Energy Technology?

Coal dehydration removes water content = lessens shipping costs?

Clean Coal Tech removes 90 percent harmful chemicals and creates a DUST FREE

coal so it cannot contaminate water ways or land! making it also safe for the AIR.