The notion of the “greedy developer” is alive and well in North America. A recent UCLA study found that the most powerful catalyst of opposition to the construction of new homes is the conviction that developers pocket too much profit. And in booming Cascadian cities such as Seattle, that belief creates a political environment hostile to homebuilding, which worsens an affordability crisis caused by a shortage of homes.

When people see new apartments with high rents, many assume it’s because developers are making a killing. But an audit of the typical costs to create and run an apartment building tells a much more mundane story: new housing is expensive simply because it’s expensive to build and operate.

My Sightline colleague Michael Andersen recently devised an auditing method that boils it down to this question: What is the rent check actually paying for? For privately-owned housing, rent income has to cover every cost: no proposed apartment building will move past the idea stage unless investors believe that it will bring in enough rent to pay for all of its development and operating expenses.

Michael found that for a typical new apartment in Portland, Oregon, the biggest chunk of rent—one third—goes to covering the cost of physical construction. In comparison, the developer—that is, the team that manages the whole project—gets just 3 percent. Add the equity investors—the early-stage, financial backers who are also commonly thought of as developers—and the total portion of the rent check that goes to the “developers” comes to 8 percent. The rest of the rent covers a laundry list of expenses including the land purchase, permitting fees, design services, interest on loans, property taxes, and more.

Bottom line: the rent is what it is because the cost of the new building is what it is.

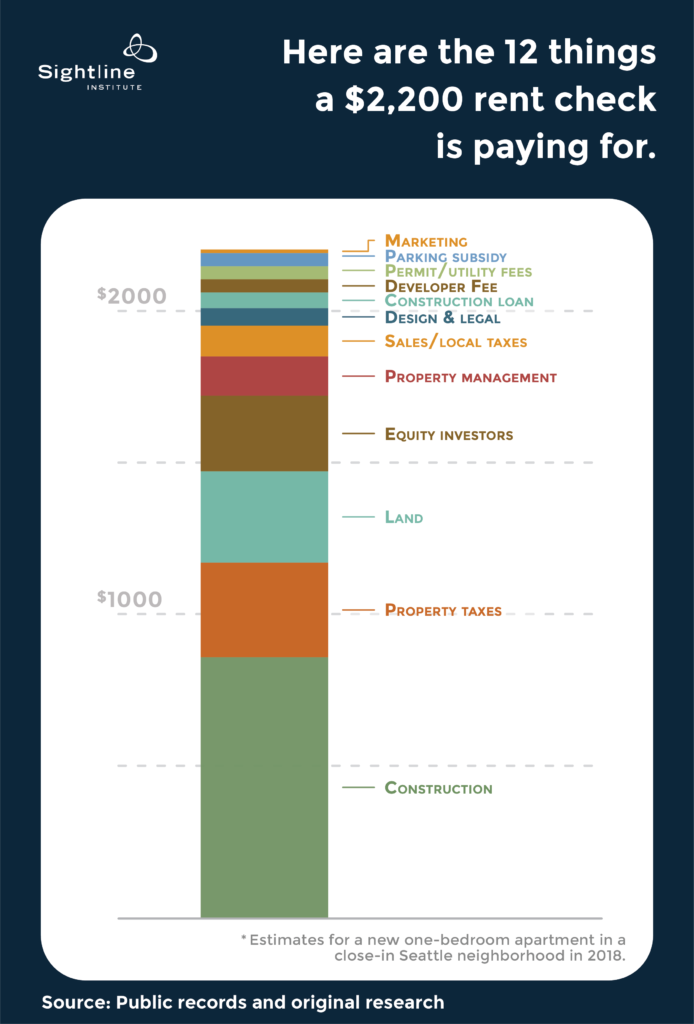

That’s such an important truth that I repeated the exercise for Seattle, running the numbers for a typical new six-story apartment building based on data provided by local Seattle developers. The results are similar to Michael’s. Construction is the biggest single cost, consuming 39 percent of the rent check.

The developer and equity investors together take 13 percent, which is more than our Portland example’s 8 percent, but in the same ballpark. So, contrary to the “greedy developer” narrative, developers aren’t getting half the rent; they’re getting around a tenth of it. Some developers may be less ethical than others—just like any other business. But on the whole, their paychecks reflect their entrepreneurial risk and effort—just like any other business.

Overall, the analysis shows that there’s no single solution for big cuts in the cost of homebuilding, which also means there’s no silver bullet for lowering rents in new housing. There are, however, ways to chip away at it, and those ways add up.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Where the rent check goes

My test case is a generic 75-unit, six-story apartment building with 50 stalls of underground parking and a small street-level retail space. As is common in Seattle, it’s constructed of five wood-framed floors built on top of a concrete bottom floor. I assume developers launched the project in mid-2014, finished construction three years later, and took another six months to fully lease it up.

Typical rent for a new one-bedroom apartment in this type of building located in a close-in Seattle neighborhood is $2,200 per month. As illustrated in the graphic above, here’s what a $2,200 rent check pays for, listed from the smallest to biggest portion:

Marketing consultants: $12/month (0.6 percent)

These folks spread the word about the building and get tenants in the door.

Parking subsidy: $43/month (2.0 percent)

What owners charge for parking usually isn’t enough to cover the cost of constructing it—a staggering $50,000 per stall for underground parking in the present example. That means apartment tenants end up subsidizing the parking through higher rent, whether they own a car or not. A typical $175 per month parking charge leaves an average $43 per month for each apartment renter to cough up.

Permitting and water/sewer/electrical connection fees: $43/month (2.0 percent)

Utility connection charges paid to city and county were $530,000, adding an average of $7,100 to the cost of each apartment. City building permit fees account for the rest, which comes to $2,100 per apartment.

Developer fee: $43/month (2.0 percent)

The main function of developers is master project manager during the entire three- to four-year development process. For this they typically charge 2 or 3 percent of the total development cost, or $690,000 in this example.

Construction loan interest and fees: $52/month (2.4 percent)

The 4.5 percent interest on the loan used to pay all the construction contractors came to $470,000. Miscellaneous fees and insurance associated with the loan added another $360,000. (Today, interest rates are one half to one percent higher.)

Design, engineering, and legal consultants: $57/month (2.6 percent)

This includes the architects and various engineers that design the building and its inner workings, and the lawyers that ensure it complies with regulations.

Sales, B&O, and real estate taxes: $102/month (4.6 percent)

Seattle’s sales tax rate, counting state and local levies, is a steep 10.1 percent, and it applies to all materials and labor that go into a building. In 2017, sales taxes on construction alone provided 5 percent of the Seattle’s total general fund tax revenue of $1.2 billion. For this example, sales tax was $1.5 million, which raises the average cost of each apartment by $20,000. Real estate taxes on the building were $64,000, and Seattle Business and Occupation taxes paid by contractors, another $35,000.

Property managers: $129/month (5.9 percent)

These folks clean, maintain, and repair the building. This figure also includes the building’s gas, garbage, water, and sewer bills, paid by the landlord. (Tenants pay for electricity.)

Private equity investors: $249/month (11.3 percent)

Equity investors put up the cash to pay for the development expenses not covered by the construction loan. They receive interest payments on their investment after the building is completed and leased up, and recover their principle when it’s sold. Equity investment is high risk—lots of things can go wrong with a large homebuilding project that takes several years to build! For this example, equity investments that accrued to about $11 million over the three and half year development would deliver a return of $4 million, which is 15 percent of the anticipated sale value of the completed building.

Land purchase: $301/month (13.7 percent)

The one-third acre of land cost $4.8 million. That comes out to $339 per square foot of dirt, and $64,000 per apartment. Customarily, developers put down a nonrefundable deposit of around 10 percent to secure an option to purchase the land later—ideally right after the city grants the permit to start construction, which minimizes holding costs. (Over recent years the cost of land has risen sharply in Seattle and sellers now often require full upfront payment, not just an option deposit.)

Property taxes: $312/month (14.2 percent)

Most Seattleites probably wouldn’t guess that property tax eats up so much of a typical rent check. State law caps Seattle’s property tax revenue increases to 1 percent annually, but recent voter-approved levies and state school funding legislation superseded that cap and boosted Seattle’s current rate to $9.56 per $1000 of assessed value. For an assumed building value of $30.4 million, the annual tax bill is $291,000 per year. Landlords usually pass those tax costs on to tenants, especially in a hot rental market like Seattle’s. In any case, property taxes are a cost that any proposed homebuilding project’s expected rent income must cover for it to get the green light from investors.

Construction: $858/month (39.0 percent)

The cost of physical construction is the single biggest share of the rent check. Seattle’s boom has inflated that portion as the shortage of skilled labor and materials has pushed prices ever higher. The construction firm Mortenson estimates that costs in Seattle rose around 4 percent annually over the past few years. Construction “hard” costs—that is, just the costs that go into the physical structure—run to $228 per square foot for the living space portion of this example. If the building had gone up three years earlier, cheaper construction could have knocked about $170 off the rent.

How much fat could be trimmed to lower the rent?

The total building development cost of $26.4 million averages to $352,000 per apartment. Scrolling through the above list reveals that when it comes to cutting costs deeply, there’s no obvious fix. Many of the cost factors are relatively small and wouldn’t help much, even in the unlikely event that they could be entirely eliminated. And there’s no easy way to abate the biggest factors—land, property tax, and construction.

For this example, the costs typically associated with developers—their project management fee plus the equity investor returns—accounts for 13 percent of the rent check. Even if that entire cost could be magically wiped out it would only reduce the monthly rent from $2,200 to about $1,900. But without the chance to earn a reasonable profit, no one would risk multiple millions of dollars and subject themselves to four years of cat-herding inspectors, investors, and contractors. Perhaps one could find socially motivated “impact investors” willing to accept a one third lower return, as Michael suggested in his Portland study? That would drop rent by a mere $80 a month.

Developers, like any entrepreneurs who take financial risks, get paid more when things go better than expected, but they also take the hit when things go off the rails. On average, their payoff is commensurate with normal standards that apply to any other business pursuit. And as illustrated in our Seattle and Portland examples, that typical payoff is nothing spectacular—it’s a modest portion of the rent check.

I’ll take a look at specific cost reduction approaches in future articles. For now, some observations:

- Construction is the big kahuna. It’s expensive to build big things! Developers have little control over the cost of labor and materials. Modular construction holds promise: if it delivers on bullish expectations to cut costs in half, it could knock down the rent check by one fourth. In contrast, cutting back on “luxury” finishes and appliances might bring a rent reduction of just a few percent.

- Seattle captures one fourth of the property tax collected, and if the city exempted multifamily housing from its portion (legally, it cannot), rent could drop by about 4 percent. Cutting the non-city portion of the property tax bill would be, well, a political fight for the ages.

- The price of land is dictated by the expected net income it can generate, which is a function of what can be constructed on it and what people will pay for that built space. Rent, in other words, flows from the local market and how many homes zoning allows on the lot. Rezones that allow more homes tend to increase the price of land, but the price of land per home usually drops, which reduces the rent check for each apartment. Over the long term, cities can minimize land prices by allowing as much new housing as possible, which keeps market rents as low as possible. (Better yet, the state or its cities could convert to a land value tax, but that too would be a political fight of Biblical proportions.)

- Eliminating off-street parking requirements at least ensures that city laws won’t force renters to subsidize parking. Seattle doesn’t require off-street parking in most locations where midrise apartments tend to be built, but investors and lenders often do. They operate in a risk-averse world where changes to parking norms established in suburban locales set off alarm bells and bring funding to a halt. My Seattle example has two parking stalls for every three apartments, a relatively low ratio by historic standards. If the building had two stalls for every apartment, the subsidy would rise from $43 to $127 per month.

- Waiving all fees for permits and utility connections could trim rent by 2 percent. Seattle is at risk of moving in the opposite direction, however; it is considering new impact fees to fund water, sewer, and transportation investments.

- Cities that force homebuilding projects to go idle waiting for permit approval boost the rent check by increasing the carrying cost of the project’s high-risk, high-return, early investments. In Seattle developers report that the typical time it takes to entitle a midrise apartment project has risen to nearly two years, almost doubling over the past decade or so. For a ballpark estimate of what that added delay would cost this example project, 15 percent interest on $3 million for a year is $450,000. That translates to $29 per month higher rent. Roughly triple that if the project had to pay the full land price up front. On top of that, though it’s hard to quantify, the uncertainty caused by just the possibility of delay can also add cost, as I discussed in a previous article.

The core rent driver: long-term yield

The fundamental link between the cost of an apartment and its rent is the yield required by investors. By yield I mean the net income generated by the building divided by its purchase price—known in the biz as yield-on-cost (see the “how the math works” endnote for details). No one’s going to sink a pile of money into an apartment building unless it can reliably deliver a cash flow that makes the investment worthwhile compared with other options such as the stock market. Institutional investors are often responsible for getting reliable returns on pension funds, for example.

The present example was financed assuming a yield-on-cost of 5.8 percent, which was typical a few years ago. But what if long-term owners had been willing to invest even if the anticipated yield-on-cost was lower? Reducing the yield-on-cost to 5 percent would drop the required rent by $262 per month, or 11 percent. Seattle affordable housing developer Bellwether tapped impact investors to partially fund two projects, offering a return of just 2 percent. At 2 percent yield-on-cost, the $2,200 rent could be cut in half!

It’s an exciting prospect, but whether it scales to more than a few niche projects depends on finding enough impact investors willing to trade financial returns for social benefit. In rapidly growing Seattle, billions of dollars flow into apartment construction annually, mostly supplied by giant institutional investors that seek to maximize returns, not social benefit. Are there people or institutions with billions of dollars to invest who are willing to accept dramatically lower returns? It seems unlikely.

Cutting costs helps housing affordability across the board

Setting public policy and regulations that will help ease, rather than inflate, the rent of new apartments depends on a clear understanding of all the costs associated with developing and operating a building. Assessing the various costs in terms of rent paid by the tenant exposes how they translate to affordability.

The main take-home point from the above analysis is: there’s no single cost factor that offers big cuts—that is, absent some as yet unproven scalable way to finance housing while paying radically discounted returns to long-term owners. Minimizing rents will require working to reduce many different factors. Conversely, every cost added by regulations, no matter how small, pushes the equation in the wrong direction, eventually leading to death of homebuilding by 1,000 cuts. Most regulatory costs also apply to nonprofit affordable housing development, raising the burden on limited public funding sources.

The second key point is that developers are not to blame for the high rent of new housing. Based on the present Seattle example and Sightline’s prior Portland analysis, what developers get paid typically accounts for around a tenth of the rent check, plus or minus a few percentage points. Advocates for inclusionary zoning or impact fees are wrong to presume that developers are awash in windfall profits ripe for extraction. The unavoidable, unintended consequence of any such added cost is either higher rents or fewer new homes.

Lastly, some readers may be thinking that even if costs are reduced, the landlord will still charge whatever the market will bear, in which case those reductions won’t help affordability. That may be true for one building at a single point in time. But what matters most is the effect on the citywide housing market over the longer term. When costs drop, developers build more, because projects with lower expected rents can still attract investors. The growing abundance of homes pushes down the whole city’s baseline average rent. That benefits all renters in the private market, while at the same time lowering the number of people who can’t afford what the market provides—and that means limited public dollars for housing subsidy can help more of those who need it.

Endnote: How the math works

The rule is simple: the rent pays for everything. That includes the paychecks for everyone who played a role in making the new building happen, along with the purchase price of the land to build on, returns to equity investors, interest on the loans, taxes and fees, and, once the building is done, the ongoing costs to keep it running.

Investors and lenders won’t put money at risk in apartment projects unless they are confident that the rent income will achieve a minimum “yield-on-cost.” Yield is the annual income from rent minus the operating expenses. Cost is the total expense to create the building and get it leased up. In 2014 in Seattle, the standard green light target for yield-on-cost was 5.8 percent. In other words, investors had to be convinced that every year the building would generate a net cash flow equal to 5.8 percent of its total development cost. (Today in Seattle investors have begun to accept lower yields in the 5.2 to 5.6 percent range.)

It follows that the rent necessary to cover a specific development cost for my example is that cost multiplied by 5.8 percent. For example, the $4.84 million expense for land must be compensated by $281,000 rent annually. Rent also must offset all of the building’s ongoing operating expenses such as maintenance, repairs, utility bills and property taxes. I excluded the small retail portion of the building to isolate the residential portion, but included the parking because it mainly serves the residents. The total required residential rent income for the building is the rent that delivers 5.8 percent yield-on-cost for total residential costs, plus operating expenses. The spreadsheet I used is here.

Jemma Nelson

Obviously land and construction are a one-time cost. But rent is ongoing, and there isn’t a developer out that that says “Oh we’ve now covered our construction costs, now we’re lowering everybody’s rent by $1150.”

So, anyone who built their buildings (100 / 5.8) = 17 years ago, in 2001 or earlier, has already paid off their investments and is now just making bank.

Dan Bertolet

Jemma –

Yes, in a booming market like Seattle’s anyone who owns property makes bank, single-family homeowners just as much as landlords.

And yes, as I noted in the last paragraph of the article, most landlords will set rent according to what the market will bear, even if their expenses drop. But lowered development costs will boost homebuilding, which reduces what the market will bear and pulls all rents down.

not a SF homeowner

of course a jab at single family homeowners…

But their “bank” is only if there is a sale and move (to a lower cost area, i.e. out of Seattle), often not in plan for homeowners.

And that “bank” is severely impacted by tax liability, selling costs, etc.

Joshua S

“The present example was financed assuming a yield-on-cost of 5.8 percent, which was typical a few years ago. But what if long-term owners had been willing to invest even if the anticipated yield-on-cost was lower? Reducing the yield-on-cost to 5 percent would drop the required rent by $262 per month, or 11 percent. Seattle affordable housing developer Bellwether tapped impact investors to partially fund two projects, offering a return of just 2 percent. At 2 percent yield-on-cost, the $2,200 rent could be cut in half!

It’s an exciting prospect, but whether it scales to more than a few niche projects depends on finding enough impact investors willing to trade financial returns for social benefit. In rapidly growing Seattle, billions of dollars flow into apartment construction annually, mostly supplied by giant institutional investors that seek to maximize returns, not social benefit. Are there people or institutions with billions of dollars to invest who are willing to accept dramatically lower returns? It seems unlikely.”

So… greed is still the main reason rents are so high? It’s just greed from investors, not developers? Seems like if we want to tackle the root cause, we should be focusing here not on driving down costs.

Dan Bertolet

So Joshua, can I assume you’ll be the first in line to invest your retirement savings at 2% instead of 5% so that it can be used to fund affordable housing?

David Neiman

I think this portion of the analysis is conflating yield on costs with yield lon equity. You can (theoretically)ask an investor to reduce their expectation for yield on equity. That’s the ~13% part of the stack that goes to the investors. But yield on all costs has a fairly sharp limit. If the YOC drops below the market cap rate (about 4.5% currently for apts), then the building is worth less than in cost to build it. Dropping below that threshold isn’t asking investors to accept a lower return, it would be asking investors to accept a negative return. Dropping to a 2% YOC would result in the investors losing more than half of their investment.

Michael D

Another factor that has changed recently is how much construction debt (aka “Bank Loan”) a Lender is willing to grant. Pre-2008, a loan of 72-75% of all construction and soft costs (design and engineering, property taxes, legal fees, etc.) was not unusual. In 2017 that had dropped to 65%, which means another 7-10% of equity needed to be raised, which, in turn increases the time (and therefore the cost) of the transaction. Also, in your example the estimated development fee of $690,000 (for the services and risk carried by the developer) looks like a big number. But the carrying costs over 4+ years of design, construction and lease-up for even a small development staff is barely covered. The big fees are on the biggest commercial projects and are earned not just by developers but by the brokers that arrange the marriage between the owner/developer and the debt and equity financing parties. As is often the case and should happen in a private marketplace, the majority of people that fit the term “Developer” are working hard to make what profit they can.

benjamin weenen

The exact incidence of a flat property/sales tax is debatable, that it is reduces landlords income ie not passed on, to some degree or another is not. All taxes on output do the same.

Affordability is a measure of prices to incomes. The best solution for tenants is therefore to scrap existing property/sales taxes and replace with a 100% tax on land rental values, as this rebates in full that part of housing expenditure.

Obviously this benefits all tenants, making housing optimally affordable for them (all else equal), but less obviously, it benefits the majority of working owner occupiers. Especially those about to take their first step on the housing ladder.

Sure landlords, banks and property developers will attempt to use poor widows in mansions as a human shield, but she can be offered roll up and deferment. It should also be conceded that the fact this is an issue at all is conformation of existing market inefficiencies which the LVT solves.

Politically difficult only due to ignorance and a lack of honest debate

Jim Labbe

“Perhaps one could find socially motivated “impact investors” willing to accept a one third lower return, as Michael suggested in his Portland study? That would drop rent by a mere $80 a month.”

See:

http://djcoregon.com/news/tag/atomic-orchard-experiment/

Sonny Kwan

This is one of the most accurate and well written articles regarding development all in one post. I have already shared this article with a number of my friends, colleagues and those who want to know more about apartments and real estate investments in general.

Matt Hays

Agreed…very good article.

Sooo many projects are proposed but never break ground, even in a supercharged economy. This is because it’s tough for developers (along with us contractors) to make projects work financially. Even with rents rising in most years (not 2018), construction and land costs have risen more quickly.

A huge element might deserve more attention: developers (and contractors) can lose money too. A lot of them lost their entire investments in projects around 2010 for example. Nobody is going to build unless that risk is at least a decent bet.

A Joy

Is there any historical reference for these numbers? I am pretty sure back in the 80s and 90s, physical construction costs were closer to 50% of overall rent. Whether I am right or wrong, the data you provide completely lacks context. It is a Polaroid picture of a 4k, 120 FPS video. Without knowing what these numbers have been over time, you cannot make the claim you do in your opening premise.

This rather developer bias piece does nothing to prove construction costs are a reason for high rents in the PNW, because it never bothers to prove present construction costs are high. It just flashes a percentage and fearmongers.

Bad form.

Ian Crozier

It’s surprising that for how well Dan’s analyzed this, he misses the elephant in the room. It’s the 5.8% yield that is the only culprit. I thank him for making this clear to me for the first time.

We could massively expand the amount of housing we build, and keep it more affordable, if developers didn’t have to rely on the private market for investment in the cost of creating housing.

This is my understanding of how Denmark’s substantial public housing stock was built – with low-interest financing supplied by the government. Many of the projects have since repaid these low-interest loans in full, so now rents are only needed to pay upkeep costs. We fund public housing in a very different manner here in the USA, but the concept of a government-backed below-market-rate housing loan provider is not the craziest thing I’ve ever heard.

Mark Wheeler

Older housing stock is also expensive to maintain. People like to talk about greedy landlords, but it is expensive to own a rental property. I’ve provided housing for 20 years & have barely broken even, for most of the years the rents were not even close to covering my expenses. Now they barely do, but still not always. It’s not an easy or super lucrative investment, yet has a very high downpayment. Interesting study, thank you!

Nathanael

So:

(1) Taller buildings mean lower land costs per apartment

(2) Less parking means lower parking construction costs — and more room to build apartments vs. parking garage spaces, so again lower land costs per apartment

(3) More apartments mean lower land costs

So, conclusion, allow taller buildings with less parking, and you cut housing costs.

Giuliana

A couple points to reinforce Dan’s excellent article and the great comments:

1. The ‘greedy developer’ trope is just that. Most developers and builders will do what they do if there’s half a chance things will work out… over the long run… because they are inspired/driven/constitutionally unable to avoid developing/building. A large portion of humanity’s optimism bias is concentrated in builders and developers because no completely rational person would take on the enormous risk present over such a long time period to get one project done let alone make a career out of it. If you doubt this go buy a lot in Seattle, even one that has an existing home on it, tear it down, get approvals, design it, permit it, and build a new one while paying yourself your usual salary… We’ll wait for your report.

2. One thing that didn’t get a lot of attention in the analysis is the cost of operating and maintaining the building once it’s completed and leased up. Typically (over thousands of buildings analyzed over almost 20 years) half the rent goes to operating and maintaining the building. Yes with a new building in a hot market with negligible vacancy you can get that down to around 40% but not over the long term because skimping on maintenance will cost you in the end. Whatever is left over goes to paying back the lenders and the investors in the hope that there’s still something for the developer. Full disclosure: A significant portion of my work involves finding under maintained buildings that can be purchased below replacement cost because they can no longer generate market rents. So if you’ve been cutting back on maintenance, repairs and CapEx for a few years let me know…

3. The thing about ‘the investors’ is interesting because even they ‘gotta serve somebody’ as Bob Dylan wrote. ‘The investors’ typically have investors themselves. With private equity they don’t get paid (other than reimbursing their expenses) until their investors (often pension funds) get X return, usually denominated in IRR which discounts future returns due to the time value of money. On the other hand pension funds by law have a fiduciary responsibility to provide returns adequate to fund essentially unknown future benefit payouts to retirees who are living longer and longer. So whatever returns they can earn only get them closer to their contractual obligations.

4. One final thing is about construction costs in Seattle, OK a couple. First we live on top of ‘The Really Big One’ fault which you can read about in the 2015 New Yorker piece of the same name. Practically that means our buildings have to be built to withstand enormous earthquake forces and that isn’t cheap. The other is that the local energy codes (in place and updated since the 1970s) require almost LEED Gold levels of energy efficiency to be approved let alone built. And that isn’t free either… but would you live in a building that skimped on either?

I could go on… labor costs due to ‘the wall’, Canadian timber tariffs, steel and aluminum tariffs… etc. but building here isn’t cheap and yet there are still those willing to do it. More would do it still if they could get land and had confidence in the approval process but that requires a longer term view from us as voters and from our elected representatives.

Giuliana

Oops, sorry meant to talk about class A apts vs class B and why nobody builds class B (or C). Maybe you can add that to my earlier:

The reason everyone is building class A apartments (for the big dollar tech people) and not more affordable class B apartments is because the incremental expense of the fancier amenities is a rounding error on overall cost of the building. Once you’ve bought and entitled the land, designed and built the building whether you go with wifi everywhere, stone counters and ss appliances is almost free on a relative basis… But this is just another argument for build more because the brand new A properties make the older As become Bs witch command less rent and they make the older Bs become Cs… rinse and repeat.

Aaron

Go ask the Seattle City Council how the hundreds of millions of $ paid by developers in-lieu of building affordable units in their projects (particularly in SLU) is being implemented for new, affordable housing projects. I’ll wait…five years later, still waiting. Better yet, how about 5 times the amount in real estate taxes that are being paid on improved, developed land vs. the dilapidated south lake union warehouses that someone here for 10 years ago can remember. Do I sense a mismanagement of funds? No reason to have public officials involved when they have $ in the coffers, yet have not and cannot follow through with providing housing like they said they would. Meanwhile, the permitting process in Seattle is pushing businesses to “friendly” Bellevue and out of Seattle.

Terry

So far I’ve seen next to nothing in myriad of articles on the cost of housing and what needs to be done about this crisis that addresses the toxic effect of global financialisation of housing –

… structural changes in housing and financial markets and global investment whereby housing is treated as a commodity, a means of accumulating wealth and often as security for financial instruments that are traded and sold on global markets.

Something to think about from an article in NEXT CITY last April:

“The global housing crisis reflects a fundamental paradox of contemporary capitalism. Cities around the world are more economically powerful and essential than ever. This creates tremendous demand for their land, leading to escalating housing costs and competition.

Meanwhile, housing has been financialized and turned into an investment vehicle, which has caused an oversupply of luxury housing and a lack of affordable housing in many cities across the world. The global housing crisis is defined by a chronic shortage of housing for the least advantaged, and in many cases, for the working and middle classes as well.

Although increasing the housing supply and strengthening renter protections are necessary and important steps, cities alone cannot address the deep structural problem of housing affordability. Where possible, higher levels of government and international development organizations will need to step in to rein in financialization and provide the affordable housing that is so badly needed.”

SF home owners do not determine the price of their property, the market does and this is where we have gone horribly wrong. Housing is a human right and we need to stop calling our homes “an investment.” Maybe then we can begin to build a livable city for everyone, not just the wealthy 10%.

Jwahl

Thank you Terry for pointing out what most these idiots can’t see. The housing market – along with healthcare and education – are wells of money being drained to fuel the emerging global oligarchy. When you can’t even find a house in Detroit Michigan without selling your spleen there are issues. There needs to be stricter rules emplaced around financing, investing, selling and building homes. Until then we can all look forward to living with our 6 other roommates at 76 years old.

Kris S.

Great article. One thing I’ve read about development of apartments in Seattle is that they’re building them to condo code in the hopes that they can be converted after 15 or so years when the laws allow them to, since condo construction has higher associated costs due to permitting and liability laws specific to Seattle.

Even if you amortize the cost of construction over those 15 years, you still end up with the initial developers making a load of money at the end of it since they have been making sustaining rental income on a $26 million property (to use your example), and then at the end they can still sell them all as $26m+ worth of condos, assuming the market supports it and they haven’t fallen apart in the meantime. I’m not sure how you would account for this in the big-picture calculations, but it does seem certain some types of development do have additional long-term returns that aren’t always taken into account.