As cities across North America consider re-legalizing duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes in low-density residential areas, housing advocates need to start asking new questions:

How many of these small, attached, relatively affordable homes will actually get built?

Where will they get built?

And for city leaders who face competing political pressures to minimize demolition but also maximize housing opportunity, is there some way to find a balance?

A much-anticipated analysis released Wednesday by the city of Portland sheds some light on those questions. Housing advocates everywhere deserve to understand what it found, because Portland may have stumbled across a formula that could work well in many cities in Cascadia and beyond.

The report from local firm Johnson Economics, hired by the city’s planning bureau to analyze a tentative recommendation from its planning commission, explored the math of Portland’s innovative proposal to do two things at once:

- Cap the size of new buildings.

- But set a slightly lower maximum size for a one-home building than for a duplex, and a slightly lower size for a duplex than for a triplex or fourplex.

In other words, Portland’s idea is to give developers of small projects a reason (other than the goodness of their hearts) to build the sort of buildings the city needs most: those with more homes inside them.

At most, a market-rate triplex (or fourplex) on a 5,000 square foot lot could be up to 3,500 square feet, which is about 20 percent smaller than this Northeast Portland triplex:

A modern triplex in Portland’s Vernon neighborhood. Each home here is 1,465 square feet. Photo courtesy PCRI.

1,217 more homes per year, mostly small and attached; only six more demolitions per year

Portland’s two-pronged proposal, Johnson calculated, delivers a lot of new housing.

The combination of sticks and carrots (none of which would require any public subsidy beyond simple enforcement) would lead to 24,333 more homes over the next 20 years than the status quo, which allows small, old homes to be replaced by big, expensive ones and essentially by nothing else.

That’s 14 times more additional housing than under the city’s previous proposal, under which duplexes would have had the same size cap as a one-home building. An earlier analysis found that the earlier proposal would create only 87 net new homes per year, drawing criticism from both pro-housing and anti-demolition activists at planning commission hearings.

The new proposal, meanwhile, would increase the demolition rate by just 8 percent over the status quo—six more homes per year.

How is this possible? Because the proposal would sharply reduce the number of times a landowner spends half a million dollars to replace one house with one house.

Or as Portland pro-housing advocate Holly Balcom put it, it’d make every demolition count.

Analysis: Low-price, lower-income neighborhoods would see no demolition

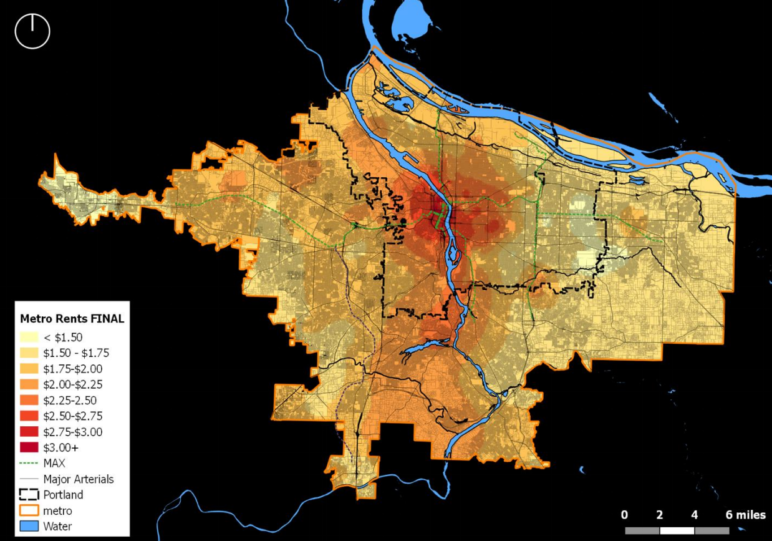

The Oregon side of the Portland metro area. Darker red = higher price per square foot of home. Image courtesy of Johnson Economics for Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, used with permission.

Another bit of news in Wednesday’s report: creating a small size bonus for duplexes and triplexes wouldn’t increase demolition rates in Portland’s lowest-income areas.

The science is not yet clear on whether redeveloping a property to add more housing accelerates displacement on its block any faster than, say, renovating a property (which also tends to eventually replace lower-income people with higher-income people, but has never been banned).

Still, there’s a legitimate question of whether poorer households—those most vulnerable to regionwide housing shortages—might end up bearing the burden of changes from zoning reform intended to (among other things) reduce Portland’s long-term housing shortage.

Johnson concluded that poorer neighborhoods wouldn’t see any more demolition, simply because newly-built homes in low-amenity areas couldn’t sell or rent for enough to cover the cost of construction, let alone buying and then scrapping a habitable home. The additional size and unit allowances proposed by the city wouldn’t change that basic fact.

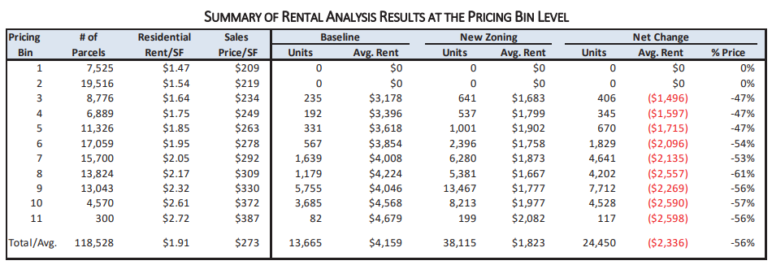

According to Johnson, new homes—and all six of those additional demolitions per year—would be economically possible only in areas where new housing can command rents above $1.64 per square foot—almost nowhere east of Interstate 205, in other words. In Portland, the neighborhoods most likely to see more housing would be those where new homes rent for $2.32 or higher: west of 82nd, north of Holgate, south of Fremont, north of Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway. (Those are the so-called pricing bins labeled 9, 10 and 11 in the table below.) The new market-rate homes in those areas wouldn’t be cheap per square foot—no new market-rate housing is. But Johnson calculated that the new homes, most of them smaller homes in duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes, would be an average of 56 percent cheaper than the big detached homes that would be built there under current zoning rules.

The new market-rate homes in those areas wouldn’t be cheap per square foot—no new market-rate housing is. But Johnson calculated that the new homes, most of them smaller homes in duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes, would be an average of 56 percent cheaper than the big detached homes that would be built there under current zoning rules.

In the same way old triplexes and fourplexes still standing do today for prewar neighborhoods, this new generation of small, attached housing would open the doors of currently exclusive neighborhoods to more people: different ages, different incomes, different wealth levels. Over the long term, it’d integrate the Portland neighborhoods closest to jobs, schools, and public transit.

This issue heads back to Portland’s planning commission for a final vote in the spring, then to its city council in mid-2019. (That’s the latest schedule, at least.) It’s unclear where the city council will come down on one crucial question: striking a politically acceptable balance between allowing more citywide displacement by not building enough, and allowing more demolition in order to add more homes.

But this study, at least, suggests to me that the city’s latest proposal is pretty close to a home run.

brett

Do the pictured duplex and triplex have alley parking or no parking?

Michael Andersen

Curbside in both cases. The duplex is three blocks from the 60th Ave light rail station (served by three MAX lines, so ~5 minute headways all day long) and two bus lines. The triplex is close to a frequent bus, and it’s on a corner so there are like 5-6 parking spaces’ worth of curb frontage.

Nothing in the plan prevents someone from building on-site parking, except in the case of narrow lots that aren’t on alleys. In that case the driveway curb cut would remove more street parking (and street trees) than it’s probably worth.

Jim Labbe

I’d gladly give up the street parking if they could put some wider green strips for larger street trees… I bet a lot of Portlanders would too.

Jim Labbe

Are the photos of the triplex by PCRI in Vernon neighborhood mean these units meet some level of affordability? That would be cool.

Michael Andersen

The triplex is pictured here for the sake of illustrating scale, but under other provisions of the proposal (not discussed here because I think they’re less controversial) PCRI and other nonprofit builders would also get a leg up in developing below-market homes for targeted folks. That’s all to the good I think.

MK Hanson

… except that even PSC member/developer Eli Spevak points out that the revised Johnson Economics study is deeply and fundamentally flawed in a way that not only over-exaggerates the projected net unit count, but erroneously under-reports projected multi-family rents.

The report applied the same construction costs per square foot across all housing types, which is not how new construction works. In the real world, heating systems, kitchens and bathrooms add considerable additional per-unit costs. So within the same 4,000 square foot envelope, it costs the least to build a single family home, next is duplexes, then triplexes, and finally the most expensive is 4-plex. As such, for-profit developers are more likely to build single family homes where land costs are high and home sales are lucrative and less likely to build multi-family on those same parcels even if permitted. So that has an effect on the number of units likely to be built and at what price-points.

However, this economist failed to include that fundamental methodology which not only resulted in extremely over-inflated unit projections, but unrealistically low rent projections for multi-family units. Stated another way, the entire purpose of the study was negated by a failure of due diligence and it is useless for modeling anything except in an alternate universe where it costs the same to build one kitchen as it does to build four.

There is also no explanation as to the 5,300 unit discrepancy between the first version of the report and this revised edition in the baseline demolition rate and the 3,686 discrepancy/change in demolition rate with zoning changes. The presumption that speculative development will not demolish existing housing in low-income neighborhoods is outside the realm of reality, particularly considering the Trump Administration Opportunity Zone creation of capital gains tax avoidance through speculating in census tracts where greater than 20% of the residents live below the poverty line. RIP intersects there as well as many other communities with a combination of current high land values, high single-family home renter population, and low median-family incomes.

Michael Andersen

I agree, the Johnson analysis doesn’t assume higher cost per square foot when unit sizes go down, but it also doesn’t assume higher revenue per square foot in the same situation. So when it comes to the crucial question of how many homes get built, which depends on both sides of that equation, those two simplifications cancel one another to some extent … and to the extent that they don’t, they would *understate* unit production a bit since revenue per square foot generally rises a bit faster than cost per square foot as unit size falls. (This seems intuitive enough, since construction costs aren’t the full cost of development, and the other costs don’t correlate nearly as much to built square footage.)

One thing I think is important to remember about this method (because it took me a while to wrap my own head around, at least) is that when it looks at projected rents in new units, it’s looking directly at the lot-level market data … like, $1800 is the price for a given predicted product because it is empirically the price people are currently willing to pay for 800 square feet of newly built housing in such-and-such nice neighborhood. So if the estimated construction costs are higher than these, the consequence is not “rents of new buildings will be high because they cost more to build!”, it’s “some of these new buildings will not in fact exist because no one will be able to turn a profit building them, in which case the current uses of the lot would remain.”

If your prediction of where one-unit vs multi-unit development is likely to occur were accurate, it seems to me we’d have seen the same pattern with recent projects: more 1:1 replacements in rich/high-amenity/close-in neighborhoods and more 1:2 redevelopments further out. Correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems to me we’ve been seeing the opposite: the narrow-lot and other density-raising projects have been more common in higher-end, close-in areas and the 1:1s are more likely to happen a little further out (though not in the actually-low-income areas east of 205). Again, this makes intuitive sense because the defining characteristic of projects in high-end neighborhoods is the cost of the land, so more land-efficient uses will generally make more economic sense there than less land-efficient ones.

I also think it’s possible to hang too much attention on the price of these newly built homes *when they’re built*. Nobody is arguing that new construction doesn’t have higher costs per square foot than old. What I am arguing is that (a) new construction is coming to the status quo anyway in the form of McMansions, and it would be better to make new housing *cheaper than it would otherwise be* by making it legal for it to be more land-efficient, and (b) older and larger homes in these areas and others will remain cheaper if small families with moderate to upper incomes have the option of moving into these relatively small but attractive homes rather than buying their way into the old homes and doing expensive remodels etc. Finally, I’m arguing that (c) these new homes that would begin their lives serving as buffers to absorb wealthier people will gradually transition into relatively cheaper homes that serve to integrate higher-end neighborhoods by wealth and income … the same role our historic duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes in old neighborhoods play today. (We can and should further broaden this last effect with incentives for nonprofit developers delivering below-market units to targeted populations … that’s also in this plan, of course.)

I had the same question as you about the dramatically lower redevelopment rate for the baseline scenario in this latest report. I’ll share what Jerry Johnson told me in an email reply:

“There are two primary explanations as to why the replaced unit totals are so different.

“The first is that we used a significantly lower rate of predicted redevelopment for each of the bins, reflecting some recent backcasting we did for Metro. This reduced the predicted redevelopment rate by almost half, and we believe is much more reliable.

Another major factor was the change in geographic coverage, with the removal of downtown areas.”

So basically I think he’s saying the previous model was (a) not informed by up-to-date information on the observed demolition rate, and once this was added the projected demolition rate fell and (b) the earlier report included a bunch of demolitions in areas not actually affected by this zoning reform proposal.

Less technically, Portland’s demolition rate has been falling pretty sharply in 2018 as new housing has taken some of the edge off the short-term housing shortage and developers have stopped being able to count on ever-rising prices for the big expensive one-unit buildings that are currently the only legal option on most lots.