Editor’s note: Oregon Public Broadcasting reported April 4, 2019, on the increase in Canadian tar sands oil being shipped by rail through Portland. Environmental regulators there were surprised to learn that not only was the amount of diluted bitumen rolling through the city on the rise, but the company responsible for the shipments had failed to disclose that the concentrations of toxic (and tank-car corroding) hydrogen sulfide gas in the product could pose an air quality risk to neighbors in the event of a spill, and would require spill responders to wear full face breathing apparatuses.

In June 2016, an oil train derailed on the outskirts of Mosier, Oregon causing mass evacuations from the town and nearly dumping more than 40,000 gallons of crude oil into the Columbia River. By sheer luck no one was harmed—a derailment just a few hundred feet in either direction could have wreaked devastation. As the plume of smoke rose, Mosier’s residents were well-aware of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, where just three years earlier a derailment incinerated half of the downtown, killing 47 people.

A June 3, 2016, wreck in Mosier, Oregon overturned 96-car train carrying Bakken crude oil. Sixteen cars derailed and four caught fire. Mosier, Oregon train derailment by Coast Guard PFC Levi Read/Wikimedia Commons (license)

These oil train explosions were not isolated incidents. After a string of high-profile catastrophes, federal regulators under President Barack Obama’s Administration belatedly began writing rules to reduce the risk of oil-by-rail transport. The US Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHSMA) and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) worked together to propose new safety rules for oil trains. But soon after the rules were finalized, President Donald Trump’s Administration threw a monkey wrench into the plan by using dodgy accounting to benefit the oil industry at the expense of public safety.

It’s a change that could put rail-side communities at substantial risk across the Northwest, particularly because we can expect to see oil train shipping significantly increase again, bound for destinations along the lower Columbia River from Portland to Clatskanie, Oregon.

Stopping Derailments

To protect communities from the risks of exploding oil trains, federal agencies in 2015 assembled a package of changes to railroad operations. One of the key rules they agreed on was so that so-called “high-hazard flammable unit trains” (HHFUTs)—trains hauling 70 or more tanker cars loaded with flammable liquids—should be required to have electronically controlled pneumatic (ECP) braking systems if they intend to travel faster than 30 mph. ECP brakes are more effective than conventional braking systems because they provide an electronic signal simultaneously to every car on the train. Conventional air brakes signal each car individually and sequentially. Because ECP systems apply the brakes to all cars at once, they slow down trains more evenly and can drastically reduce stopping distance. It’s indisputable that brakes help prevent derailments and, when derailments do occur, ECP brakes reduce the number of cars that end up falling off the tracks, thereby reducing the likelihood that an oil-laden tanker will puncture or explode.

Yet in December 2015, about six months after the new rules were adopted, Congress passed a new law compelling the Federal Railroad Administration to re-study the efficacy and costs of ECP brake systems—and to repeal the brand-new rule if it no longer passed a cost-benefit analysis. The law might not have resulted in any changes had FRA still been operating in the Obama Administration. But working under the Trump Administration, FRA officials significantly lowered their appraisal of the public benefits of the new brake rule and rescinded it in September 2018, concluding that increased public safety no longer superseded the costs for the railroad industry to upgrade its cars with better brakes.

FRA’s “updated” analysis appears to be riddled with errors, though. In a review of federal documents, reporters for the AP found that government economists omitted the most common type of train derailment from their calculations, excluding from the final tally benefits worth something to the tune of $48 million to $117 million.

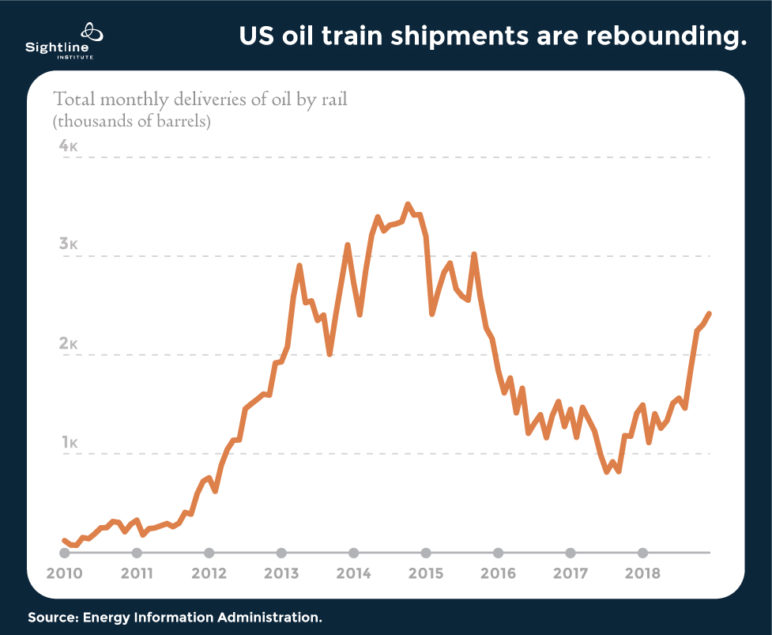

Plus, PHMSA and the FRA low-balled their predictions for oil train numbers, an assumption that tilted the analysis in favor of the industry. The volume of oil shipped by rail in the US had skyrocketed from just over 20 million barrels in 2010 to more than 373 million barrels in 2014. Nationwide oil-by-rail volumes dropped in subsequent years, but trains loaded with crude continued to roll through the Northwest in numbers near the 2014 peak. The Trump-era agencies concluded that the dip in oil-by-rail shipments in 2016 was indicative of the future, so they lowered their forecast for the volume of oil that would be shipped by trains over the next 20 years. Yet domestic oil-by-rail shipping is up. Late 2018 figures show a year-over-year increase of almost 40 percent.

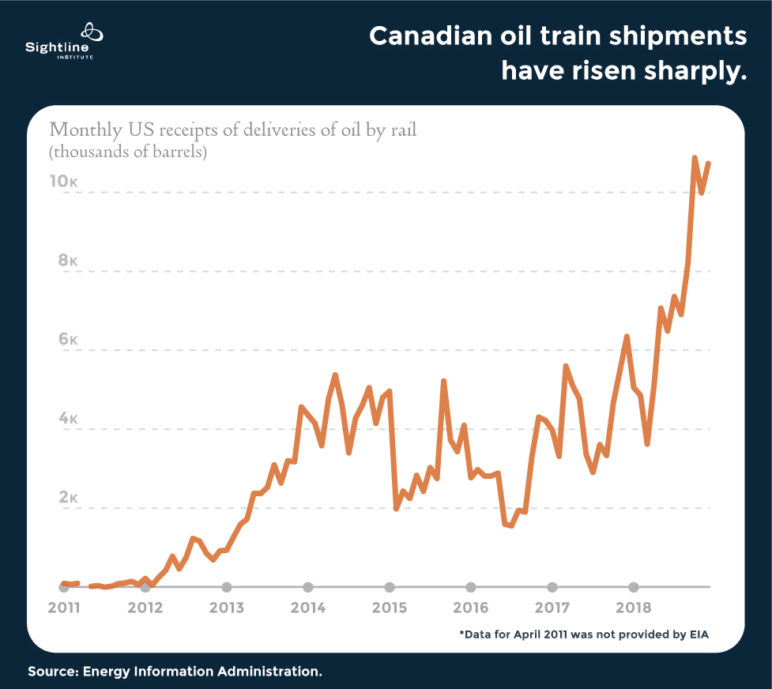

Even more troubling, the new analysis appears to ignore oil trains coming into the US from Canada. It so happens that Canadian oil train numbers have increased substantially over the past few years, in part owing to delays in building the big new export pipelines that the oil industry wants.

Even more troubling, the new analysis appears to ignore oil trains coming into the US from Canada. It so happens that Canadian oil train numbers have increased substantially over the past few years, in part owing to delays in building the big new export pipelines that the oil industry wants.

Analysts expect the number of Canadian oil trains operating in the US to double again by the end of 2019 and, in fact, the government of Alberta is planning to buy its own railcars and locomotives in order to ship an additional 120,000 barrels of oil by rail per day to American refineries and port terminals.

Analysts expect the number of Canadian oil trains operating in the US to double again by the end of 2019 and, in fact, the government of Alberta is planning to buy its own railcars and locomotives in order to ship an additional 120,000 barrels of oil by rail per day to American refineries and port terminals.

Whether the public ever gets a chance to weigh in depends on an administrative appeal filed by Earthjustice, an environmental law firm. They are arguing that the US Department of Transportation failed to conduct the Congressionally-mandated safety tests; lowered its estimates of crude-by-rail accidents and risks based on faulty assumptions; and allowed only limited public comment before the required tests and information were made public.

Because the Northwest is a prime a destination for crude from both North Dakota and Canada, the Trump-era rollback in protections means greater risk for communities all along the rail lines from Spokane to Portland to Tacoma and beyond. Not even seven years old, the region’s oil-by-rail industry has proven itself to be an extreme threat to communities and wildlands along the rail line—a hazard that could be mitigated with rules requiring explosion-prone trains to use the most effective brakes available.

Phoebe Barnard

Fascinating article, thank you. What are the safeguards, if any, for oil trains in the event of an earthquake?