The people planning the Portland area’s next light-rail line seem to be steering away from a scenario where taxpayers waste $100 million of precious public-transit funding on a series of giant parking garages.

But unless the public speaks up in the next month, it’s possible that a handful of elected officials will push to build the garages anyway—despite a mountain of evidence that spending the money on bus service, infrastructure for walking and biking, and transit-oriented affordable housing would do far more to improve mobility, reduce auto dependence and cut pollution.

TriMet staffers seem to be looking to “update their approach” to park-and-rides based on a closer look at the factors that actually drive transit ridership, says Ramtin Rahmani, a volunteer on the community advisory committee for the Southwest Corridor Light Rail Project.

Rahmani said last week (speaking only for himself) that TriMet’s staff members are making the case for surface lots instead of multi-level garages at several stations along the new rail line through Portland, Tigard, and Tualatin, except at the end of the line near Bridgeport Mall. Their theory is that transit funding is better spent elsewhere and the surface lots would preserve the option of adding housing later.

This proposal isn’t perfect. TriMet has indeed redeveloped a few park-and-ride lots over the years, but it’s rarely removed parking spaces when doing so. That’s probably because, even if land values rise in an area and development becomes more viable, each free space becomes an increasingly valuable entitlement that car commuters are willing to fight for.

That said, as I argued in November, surface lots are less bad than free parking garages. Here’s a slightly updated version of what my Sightline colleague Madeline Kovacs told the rail line’s community advisory committee when it met last week:

At $52,000 per stall, free park-and-ride garages are among the least effective ways taxpayers can spend money on public transit.

TriMet records show that 38 percent of MAX park-and-ride stalls sit empty on a typical weekday. But even if we generously assume a vacancy rate of just 20 percent for Southwest Corridor garages and a 45-year lifespan, then taxpayers are spending about $7 for every weekday a space will be used. The region’s taxpayers would be essentially buying more than the equivalent of a free transit pass for anyone who shows up at a garage, on one condition: that they show up in a car.

If we want to maximize transit ridership, park-and-rides are far less effective than other options. A 2016 King County Metro analysis found that capital investments to improve bus speed and reliability created more than three times as many riders per dollar as free park-and-rides. TriMet’s own analysis projected that even if several new garages are built for the Southwest Corridor, 85 percent of future trips will come from foot, bike or transfer traffic, not park-and-rides.

If we want to minimize congestion and pollution, the meaningful answer is not to convince 200, 300 or 500 cars—out of the 300,000 that drive to jobs in Portland each day—to pull off I-5 a few miles farther south. The answer is to make transit an efficient and attractive option without requiring auto use in the first place.

This can mean improvements to bus, walk and bike connections to rail. $100 million would be enough to install networks of low-stress protected bike lanes for miles in every direction around all 13 Southwest Corridor stops. It can also mean creating mixed-use, mixed-income developments within walking distance of rail stops—something that becomes much harder if you already dedicated the prime land near your rail stop to parking lots and garages. $100 million would be enough to create or preserve 600 more affordable homes along the corridor.

If we want to improve mobility for lower-income people, the solution is not to offer free parking to several hundred car-owning downtown workers in the hope that some of them might be poor. The solution is to spend the money on things we know disproportionately benefit low-income residents: better bus transit and affordable housing near transit. Both of these also boost overall transit use, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that helps improve the system for everyone.

Finally, even if we don’t care about any of the above goals—if the only issue that motivates us is to prevent parking spillover onto nearby streets—there is again a way to do this that costs taxpayers much, much less than free parking garages. Local permit districts are a simple way to eliminate “hide and ride” behavior. If a jurisdiction wishes to give exclusive permits to residents for free, that’s still far cheaper than a free garage. Or if a jurisdiction prefers to raise money for whatever it wants, it can offer parking permits to commuters for a price.

The huge cost of new rail lines can sometimes make park-and-ride garages seem cheap by comparison. They are not. The cost of building something great, like a new public rail line used by tens of thousands of Oregonians, shouldn’t be allowed to conceal the boondoggle of free garages. Our region desperately needs to spend this money on things that will matter more.

Happily, TriMet staffers made some of the same points themselves to the advisory committee Thursday night. Take a look at this section of their slideshow. (Slide 41, for example: “Parking is expensive.” TriMet puts it at $52,000 per garage space and $18,000 per surface lot space, plus $1 per space per day to operate.)

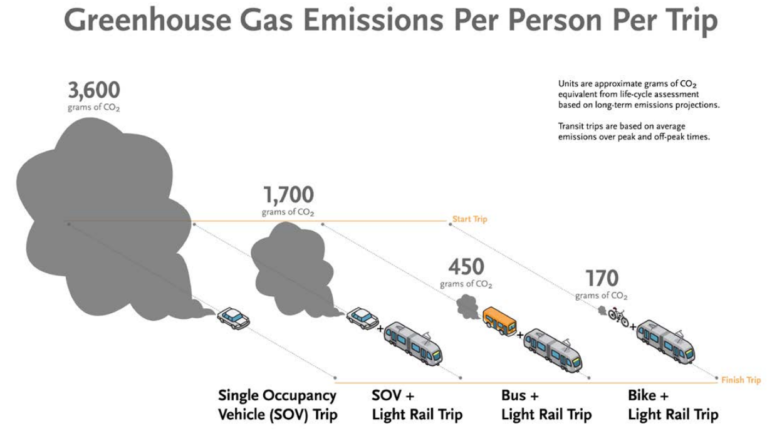

TriMet’s staffers also shared this image comparing greenhouse gas pollution for driving alone, for driving alone to a park-and-ride, and for taking bus or bike to a rail station:

Shifting a trip from car to bus-plus-rail is 67 percent better at cutting carbon pollution than shifting it from car to park-and-ride. Graphic courtesy of Los Angeles Metro. Data from Chester et al, Infrastructure and automobile shifts: positioning transit to reduce life-cycle environmental impacts for urban sustainability goals.

TriMet’s park-and-ride dilemma isn’t unique. As noted above, King County Metro went through a similar number-crunching process in 2016 and concluded that giving dedicated lanes and traffic signal priority to buses would bring in three times as many new riders per dollar as larger park-and-rides. Sadly, that work didn’t stop the Seattle area’s suburban light rail expansion from promising a gobsmacking $700 million of new parking spaces.

Something similar could happen in TriMet’s process. The Southwest Corridor Steering Committee, which consists mostly of elected officials from suburban jurisdictions, will effectively decide how many transit dollars and how much transit-adjacent real estate to dedicate to park-and-rides, even within the City of Portland.

This rail line could instead become a new model for the Pacific Northwest. One possibility: The agency could scrap its garage plans and solicit proposals from outside the agency for mixed-income housing developments. If a new building (probably with some shared parking on-site) can generate more transit riders than a parking lot alone, it could be allowed on the site instead.

Another option: The regional 2020 ballot issue that’s expected to fund this rail line could give cities money to install networks of protected bike lanes around each stop. That, along with relatively dense suburban station areas, can be the “secret weapon” of suburban transit ridership.

TriMet’s steering committee will briefly take up this issue at a meeting next week, and will go into depth at its meeting on June 10.

Free park-and-rides might seem a boon for transit use. But look closely. They’re not: They soak up money that would be better used making transit better and easier to access. Yes, garages are visible. But that visibility is just a monument to our failure to make transit more attractive than driving in any way but one: free parking.

To their credit, a growing number of transit agencies realize this. But getting an agency’s leadership, always sensitive to political pressures, to listen to its own expertise on this subject often requires persuasion—sometimes from its staff, but also from members of the public.

Johnny Come Lately

nope, no amount of busses will replace being able to drive that extra couple miles home. Guarantee if you would like to throw the baby out with the bathwater, by all means rely on people “bicyling” and “running” to the MAX when in absolute reality. . .

cars aren’t going away

people will not walk two miles to your MAX

they will instead drive to work

and the MAX will be an even bigger boondoggle than your thoughts on parking garages are.

Maximize use of the MAX, ensure people have a place to put their cars. If you’re low income, great news! MAX offers you half price on the ticket you’re not about to spend a single dime on anyway. So, doing away with the parking garages will only force you onto a bus. In which case, you’re definitely paying now.

But hey, at least this drivel didn’t push for free max rides for the poor. Shame that the extra money won’t go into their favorite craft brew but instead to pay for their portion of this enormous infrastructure.

jay wash oh-ah

I am curious to know – do you ride the MAX now? like as a commuter or otherwise?

asking as a regular person who happened onto this article and then your comment

Alton Henson

It is my hope that the ideas expressed and proposed in this article become actions of norm soon. Great piece.

rick

keep it going. build jobs, not car storage. Why can’t we simply reroute numerous bus lines instead of this light rail project ?

Yea Right

Sure, be just like the Bay Area, leave no place for commuters to park so you loose them as Max riders. Max is slow enough, add the extra time a bus leg of the journey would add including the walk to/from bus stop and it’s simply impractacle for working parents to spend about 1.5 hours each way to travel 12 miles. What’s your next idea, make it a crime to own an auto?

Michael Andersen

One great thing about improving non-auto transportation and charging for auto parking is that it frees up road and parking space for people who do truly need to drive.

The argument here is that people who want to drive to the MAX should have every right to pay to access private parking garages near stops. Makes no sense for taxpayers to do so for them.

BK

This is a bit–but not entirely–tongue in cheek, but it seems as if it’s likely transit agencies would generate more ridership and possibly more political support if they re-deployed funding for parking toward a lottery. That is to say, each time you swipe your card on your commute you have a chance of winning cash money.

In all seriousness it seems more efficient to incent and reward folks who might be on the bubble about taking transit than trying to win over a tiny amount who require free parking…

(If anyone could figure this out it’s Sightline 🙂 )

jay wash oh-ah

to your knowledge have free rides on a transit system ever been made available to people who are riding from far out nodes? kind of like the opposite of what Portland had going with fair-less square. maybe just free on the way in. its an idea which occurred to me recently and thought you might know.

Michael Andersen

Interesting idea! Never heard of this, though I have heard of something similar: in the 1920s, when Chicago’s El system was still privately operated, the city mandated a fixed fare for all passengers no matter how far they were going.

Unfortunately, this was part of a death spiral for the transit system’s ridership, starving it of revenue even as the city was using gas taxes (which people did have to pay more of when they drove more) to invest heavily in road paving and expansion, which led cars to dominate Chicago and every other major US city except NYC. I’m not saying this would be the case for the scenario you mention! Only that limiting the cost to access a valuable system may sometimes make the world less fair.

Charlie Weiss

SW Portland has its issues — topography prevents a grid; circuitously-dispersed residences resist efficient logistics; lots of people not headed downtown and/or not traveling during commute hours. (Our 2000 research made those points clear.) One suggestion was frequent micro-bus service where big buses don’t work, continuously-improved schedules & routes determined by users’ needs, to feed the transit corridors. And public-transit destinations other than downtown. Dream on?

Bob

Argument seems crankish and unrealistic which is typical of planners. What the author is advocating for is by far the most costly and yet he tries to warp the conversation to make it look viable.