Critics of congestion pricing argue that the policy favors the rich and hurts the poor. A new proposal to break gridlock in downtown Seattle offers a progressive approach to get traffic moving. Few low-income households would pay the toll and the revenues from higher-income households could put free, multi-modal transit passes in the hands of low- and moderate-income people who travel to downtown.

Workers in downtown Seattle—Cascadia’s biggest jobs hub—who earn less than the median income of $35 per hour would, as a group, receive more money for mobility than they would pay in tolls and transit fares, according to the proposal. They would also waste less time stuck in traffic because commute speeds would increase by as much as 30 percent.

Washington has the most regressive tax system in Cascadia or, in fact, anywhere in the United States, so any plan to make transportation fairer and faster should get a close look. Because of Washington’s exclusive reliance on sales, gas, excise and property taxes, the poorest 20 percent of households spend nearly 18 percent of their income on those taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent pay just 3 percent.

In 2014, state and local governments within the four counties of central Puget Sound levied $7.8 billion in taxes to pay for roads, transit, and ferries that fell most heavily on the poor. With gas tax revenues projected to fall because of rising fuel efficiency and vehicle electrification in the next decade, the region needs a new approach. Fortunately, one has recently emerged. It’s called Fair and Efficient pricing and it’s the brainchild of Matthew Kitchen of ECONorthwest, a local economic consulting firm.

Kitchen used to work at the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), which develops long-term transportation plans, so he knows his way around the regional data. He took an enormous dataset of regional trip-making behavior from PSRC and combined it with new public data from Uber (the study sponsor) on hour-by-hour travel speeds on the street network. He mixed in local research on how drivers respond to price changes and insights gathered from other toll projects across the country.

From all the number crunching emerged a picture of how Fair and Efficient pricing could work in Seattle:

- Auto travel time to and from downtown would decline by 30 percent during the morning and afternoon commute.

- Bus transit speeds would increase, and so would ridership. Consequently, transit trips into downtown would increase by 4 percent, even without investments in new transit service.

- Auto trips during commute hours would decline by 7 percent.

- Tolls would range from zero on weekends, between 11 pm and 5 am on weekdays, to $1.50 at midday to $3.80 during the afternoon rush hour.

- Drivers would only pay once, for the most expensive hour the vehicle traveled within downtown. The maximum charge any private vehicle would pay per day is $3.80. Uber, Lyft, and taxis would pay a charge per ride delivered.

- The program would generate at least $130 million per year in gross revenues.

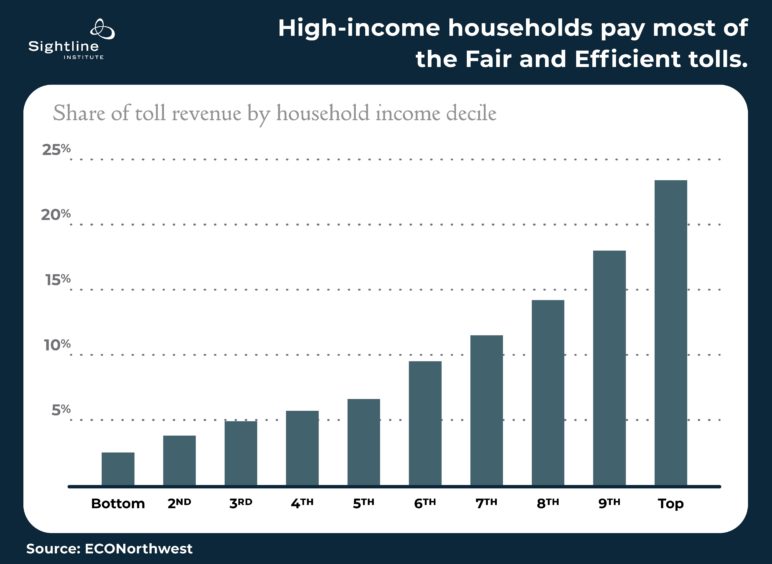

The analysis also shows that high-income households would pay most of the toll revenue, which makes sense because high-income drivers make up a disproportionate share of the auto trips into downtown.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

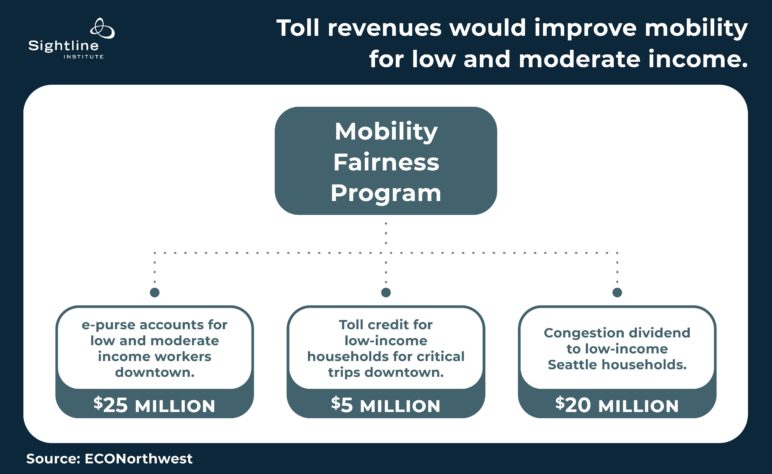

But for those households earning less than the regional median income (the left half of the chart above) who need to drive into downtown, the toll rates would still represent a larger share of their income than for the higher income groups. To stem this regressive element of tolls, the Fair and Efficient plan devotes $50 million of the more than $130 million in gross revenue to fund a three-part Mobility Fairness Program.

The first part involves all employers with workers in the downtown area administering a new transportation benefit for employees whose incomes are near, or below, the regional median. Think of it as an e-purse or super Orca card of $85 per month that can pay transit fares, bike-sharing expenses, shared-ride fees, parking charges and tolls. Workers downtown who earn less than $35 per hour would receive toll revenues back in the form of the super Orca card independent of whether or not they pay tolls. For workers who pay the toll daily to enter downtown Seattle, the e-purse would offset daily toll expenses. For workers who avoid the toll entirely by taking transit, the super Orca card would represent new money in their pocket.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

The second part of mobility fairness would provide rebates to offset toll charges associated with important trips into downtown by low-income households that qualify for programs such as Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Hospitals and other essential service providers would validate visits by qualifying households so they can receive a credit on their toll payment account, much in the way some medical providers validate parking in nearby garages. Finally, some 30,000 Seattle households with the lowest incomes that qualify for the city’s utility discount program would receive a super Orca card worth $50 each month to ensure better mobility for the low-income.

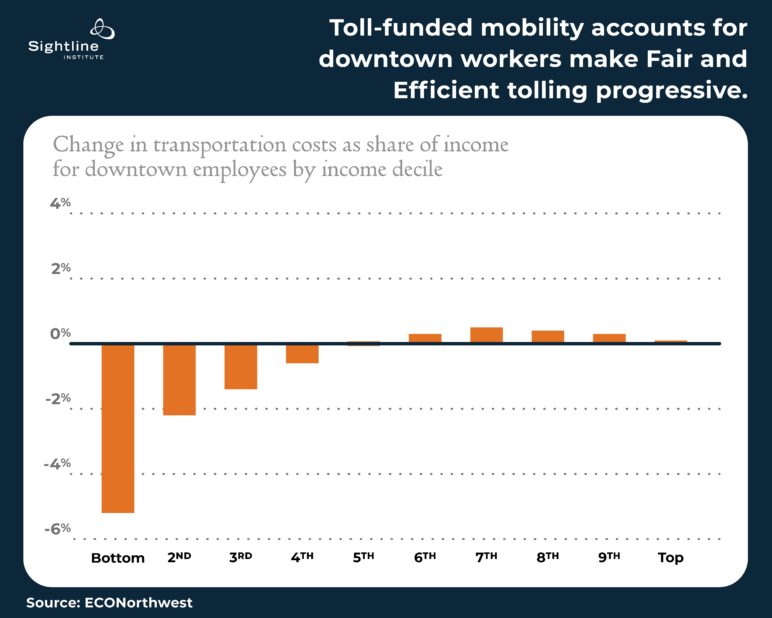

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

For low-income workers downtown, the Mobility Fairness Program would represent a meaningful decrease in costs. For those earning close to minimum wage, the value of the super Orca card after subtracting what they would pay in tolls is more than 5 percent of their annual income.

This new study lands just weeks after the City of Seattle published its Phase 1 summary report that surveyed the lessons from other cities that have implemented congestion pricing solutions. The Fair and Efficient plan offers a promising approach that cuts congestion and improves equity that the city will want to consider as it moves into discussion with community stakeholders about next steps.

Polling shows little enthusiasm for congestion pricing now. But experience in cities that implement pricing shows public opinion can flip from opposition to support when the benefits become obvious. A plan that cuts traffic by 30 percent and puts money in the pockets of low- and moderate-income workers could start to tip the balance in Seattle, setting an example for cities across Cascadia and beyond.

Disclosure: Uber has authorized a grant to Sightline Institute to underwrite a portion of an effort to convene stakeholders in Seattle to discuss congestion pricing. Daniel Malarkey served as a third-party reviewer of an early draft of the ECONorthwest study described in this blog post.

Editor’s note: We’ve clarified the article to reflect what type of vehicle would pay for rides downtown in the fifth bullet point that spells out how Fair and Efficient pricing could work in Seattle.

Mike

So Uber is lacing the pockets of various lobbying groups and those groups came up with a plan that benefits Uber with a one-time fee for its drivers to drive in circles all day long while regular citizens pay the same amount to just get in and out of downtown even if they only travel a couple blocks on the city street. Like with the soda tax, the proponents who actually care about congestion (and not making ride sharing services money) will be sadly disappointed when congestion isn’t actually reduced by this misguided plan. Any plan that doesn’t tax distance traveled or at least individual trips in and out of the restricted zone isn’t congestion pricing, it is a naked ride sharing subsidy funded by taxpayers.

Funny how nobody is proposing that we regulate ride share vehicles like the taxis they are with a defined set of “virtual medallions”. You could quickly remove quite a lot of congestion that way without having to resort to regressive taxes. And existing transit is such a great option in Seattle, particularly downtown, that nobody will miss those ride share vehicles being off the roads, right? I mean we have a train to the UW and some street cars, so we’re basically on par with Manhattan or central London now as a world class city.

Daniel Malarkey

Mike-

The approach to congestion pricing for downtown Seattle that ECONorthwest modeled in this study applied the daily charge to each separate passenger trip that Uber or Lyft would carry into downtown. This study was designed to estimate the toll levels that would reduce congestion and show how the tolls would fall on different groups. The key principle in the toll design was to ensure that all vehicles, to the extent possible, bear the congestion costs that they impose on the road network. If the city moves forward with a pricing program, there are lots of important details to work out to ensure that it doesn’t unduly favor or disfavor a particular class of drivers.

Thomas

This is wrong. The study explicitly ignores the possibility of multiple trips being made in the same vehicle on the same day. It assumes that each trip in and out of downtown results in a single charge (whichever boundary crossing produces the higher toll), and models the demand response accordingly. Uber and Lyft operations are not even considered.

The proposed policy—very clearly stated as one charge per vehicle per day—will in reality use tolling to push people from personally owned cars to Uber and Lyft, whose cars will drive nearly twice as many miles for the same passenger movement, while being nearly immune to the congestion pricing scheme. Without policy designed to account for this, the study’s projections are virtually meaningless.

It’s hard to believe that someone of Daniel’s experience would not recognize these insidious implications. This analysis is either a serious embarrassment or a sign that SI’s integrity has been compromised by the relationship with Uber.

Billy Poobah

True to your name this proposal is full of malarkey (shit)!

Nancy Padberg

I live 47 miles from where I work. I carry a backpack, a briefcase and sometimes bags of food with me. I can’t decrease this load. I have tried. And what do I do when it is raining? Carry an umbrella as well? I am almost 64 yrs and have over 6 yrs till I retire. With no traffic my drive takes 1 hr, with traffic up to 1.5 hrs. Having to drive to an area where I can catch mass transit would add even more time. And where would I put my backpack, briefcase, etc.? I am already stressed raising teenage grandkids, taking them to events and medical appointments. This would just add even more stress.

MARTHA JORDAN

What specific geographic (i.e. street) boundaries are being discussed for when this toll is charged? How much will it cost to collect the toll? And what about the casual traveler or tourist who visits downtown Seattle and does not have a pass or whatever the system is? Do they get dinged an extra fee for either not knowing or not having the appropriate sticker, tag, tab or ? I will assume traveling north or south through on the I-5 corridor and not exiting in Seattle will not trigger a fee.

Daniel Malarkey

The boundaries are from South Lake Union on the north to the baseball stadium on the south and from the waterfront on the west to Broadway on the east. You can see a map on page 24 of the study which is at the second link in my article. The costs to collect the toll would be between 10% and 20% of the revenue but the details about the particular technology were not explored in the study. That technology choice will affect how occasional travelers are charged. The proposal did not apply a toll to I-5 or I-90.

asdf2

Within the realm of Uber/Lyft trips, the congestion fee has to be per-trip. A fee that’s per-driver-per-day doesn’t make any sense.

Ideally, such a fee would be structured to encourage people who are unable to take public transit all the way home to at least ride it to a Link station or bus stop outside the congestion zone, and have their rideshare driver take them the rest of the way from there. To give a concrete example, we would like people Ubering from downtown to Maple Leaf to have their driver meet them at UW Station, rather than in the middle of downtown. This could be done by crediting a portion of the rideshare congestion fee to the customers’s Orca card, so the transit fares would not a deterrent, and also requiring Uber and Lyft to suggest this in their app and point out much money money it would save. In many cases, riding Link outside the congestion zone would actually save passengers time as well as money, since it eliminates driving through the most congestion areas, and the driver can even be already heading to the pick-up point while the customer is riding the train.