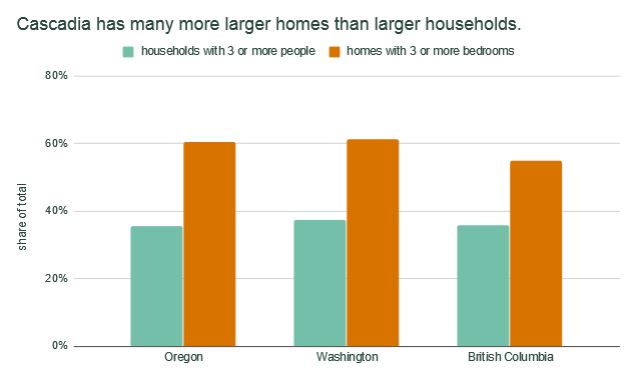

Across the Pacific Northwest—Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia—only 37 percent of households consist of more than two people.

But fully 59 percent of Cascadia’s current housing stock has three or more bedrooms.

Even in the city of Portland, it’s 49 percent of homes with three or more bedrooms despite only 34 percent of households with three or more people. In Seattle proper, the oversupply of big homes is 38 percent compared to 26 percent.

Is it bad that so many of us have bigger homes than we truly need? Well, maybe. The United Nations says it’s a significant contributor to climate change, for one thing.

The fact that one person has plenty of indoor space doesn’t in itself force another person to have less … unless we’ve passed laws that limit the construction of new indoor space. And of course we have many such laws. Bans on adding more apartments to places many people want to live are a primary cause of housing scarcity in the United States and Canada. Apartment bans are the single biggest thing preventing us from having a housing market that feels more like a grocery store than a cage match.

And in most cities, our zoning laws have indeed pitted us against each other. Every time a zoning law makes it harder for a household to find an attractive small or downsize option, it does a little bit of harm to everyone else. A small household ends up in a large home, and larger homes become a little bit more scarce.

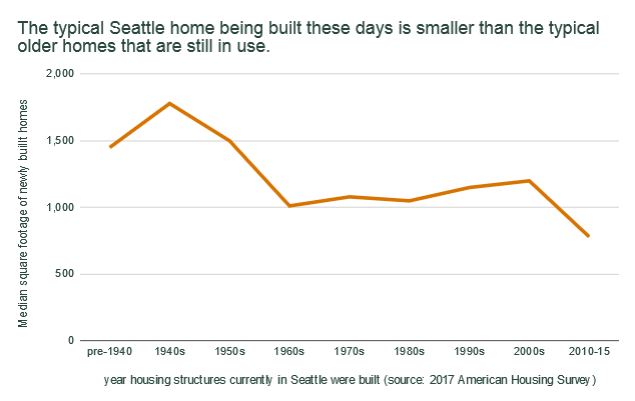

In any case, this mismatch between home sizes and household sizes also explains a thing some people find troubling: Especially in the biggest cities, most newly built market-rate apartments are smaller than the homes that already exist.

Markets fail all the time, but this isn’t one of those times. Just the opposite: This is what it looks like when a housing market is allowed to respond to a demographic trend—in this case the trend toward smaller household size. Households of either one or two people account for an estimated 52 percent of metro Seattle’s net household growth since 2005, 59 percent of metro Portland’s and 69 percent of Greater Vancouver’s.

A lot of that is from people living longer. Some is from people having fewer kids and starting families later in life. Some of it is perfectly normal in any region where relatively plentiful jobs, vibrant downtowns and a beautiful environment have lured or retained many thousands of young adults.

If most existing homes are bigger than the typical household needs, of course most of the new homes built are going to be small.

This is exactly what markets are actually really good at: aggregating millions of private decisions by reasonably comfortable people—those who can afford to consider newly constructed buildings—about what’s right for their own households. Markets are good at this even when a lot of people find the truth surprising.

Collectively, the millions of homeseekers who together make up Cascadia’s housing market are helping the region fill this need by spending their money on smaller homes. That’s why small homes take only a few weeks to fill up, just about the same as big ones. In big cities, our market is trying to build more small homes at almost every chance it gets. Thank goodness.

Letting smaller homes exist is the key to keeping larger homes cheaper

The most expensive 2-bedroom in this Portland 12-plex, a few blocks from frequent bus and rail in Portland’s Hollywood neighborhood, is 5 percent cheaper than the single-detached 1909 home the building replaced. Photo by Michael Andersen, used with permission.

None of this is to deny a different, related problem: many households have more than two people, and do need relatively large homes. And large homes in the Pacific Northwest, like almost all homes in our otherwise prosperous region, are expensive.

In the case of newly built subsidized housing, prioritizing some large homes makes sense. Many families in need are eager for the chance to live with grandparents, siblings and so on. Under normal formulas, residents will pay more for those larger homes, even after subsidies. But for many people, the household community the larger homes enable is well worth it.

Then there’s the more than 80 percent of low-income Cascadians who rely on market-rate housing.* What’s best for this subset of us? When poor people aren’t receiving subsidies but need larger homes, can we do anything to help the market provide them?

It’s not going to be easy, because building things costs a lot of money and building bigger things costs even more. This is one reason it’s important to have some small homes mixed into every neighborhood: it gives people with less money the option to put their limited funds toward a valuable location instead of a large home, if location is more important to them.

But outside the realm of subsidized housing, there is one thing we can do to help poor people find larger market-rate homes for less money: We can make living space less scarce.

There are two main ways to make that happen: allow more homes inside each building, and let buildings be larger.

Sometimes this just means a renovation that turns an unfinished basement into an apartment, or replaces a garage with a cottage. Sometimes it means a whole new apartment building. Either way, we’re creating small homes that give middle- or even high-income singles and couples somewhere to live, allowing a cascade of voluntary relocations that will free up bedrooms in larger, shared homes that would otherwise be perfect for a larger family.

This is the same process of new homes opening up existing homes that Evan Mast of the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research described at the city level in a paper published in July. In a separate paper published in October, Xiaodi Li of New York University found that newly constructed apartment buildings tend to reduce upward pressure on rents in nearby buildings even within 500 feet.

And here’s one thing that definitely won’t make bigger homes cheaper: forbidding new homes from being small, as recently proposed in Des Moines, or (phrased a different way) requiring them to be big, as recently approved in Seattle. That’s a good way to prevent small homes from existing, but it can’t make the market build big ones, because there’s no magic that’ll make more of us able to afford them.

Some people don’t want small homes, and they shouldn’t be forced to live in them. But anyone who does want to prioritize their preferred location over a big home should have that option. It’s an option that fits more Pacific Northwest households every year.

* This is a conservative estimate based on 2012-2016 Department of Housing and Urban Development data for Oregon and Washington, the 2016 Canadian Census, and this report on Washington’s MFTE program. Adding all households in these subsidized rentals together, and assuming that all US households in subsidized housing are low-income, suggest that 13 percent of all low-income households are in regulated-affordable housing. I considered a US household “low-income” if its income was less than half the median calculated for its area, and I considered British Columbian households low-income if they had incomes below $20,000 Canadian, or below $30,000 for households larger than one.

BK

Wow – thanks for flagging the (bad) Seattle size requirements of minimum 850 SF for 2 BR and 1,050 SF for 3 BR apartments under MHA. This will needlessly make those apartments more expensive. I can attest from experience (I grew up in a 1,000 SF apartment) that you can get a small but still “American style” 3BR experience in less than that. But more important I’ve chatted with a guy in Singapore whose family lives (happily) in a 3BR 650 SF apartment – by US standards he describes the bedrooms as “more like sleeping closets.” But that’s fine – if the City is regulating anything it should be to encourage creative ways more people can be housed for less by looking for innovations that have worked elsewhere – not prohibiting them!

Michael Andersen

Credit goes to Dan for knowing that about MHA and pointing me to the link!

Agreed re innovation dissemination.

Nancy Padberg

Having people “living” in a house, doesn’t mean that’s the only people who stay there. MANY homes will soon be housing their elderly parents when in 2035 there will be more people over 65 than under 18 for the first time in history. I am raising my two grandkids in a 1500sq foot home with 3 bedrooms. Their uncle comes up almost every weekend to help get things done around the house and property. His friend may come with him to help cut down trees or build a shed or move wood. They spend one or two nights per week. I am 64. When I get in my 90’s he or one of my grandkids may move in with me to help care for me. It is already happening and it is going to happen even more every year. LOOK at demographics and plan for it.

kathy johnson

I’ve been trying to build a DADU in the city of Seattle now for 14 months. I am into this now for $50k and still don’t have a permit. The cost estimate to build a garage with a 800 SF apartment. The cost estimate to build this is over $500K. Banks will not finance the DADU since there is no income stream. How is the average homeowner, who has the space and has the desire to provide a DADU supposed to finance this if the banks will not.

If the city was serious, they would provide a funding mechanism so that us single person home owner who is middle class with a mortgage supposed to afford it?

RDPence

Tell the banks you are putting your DADU on Airbnb~ you’ll have plenty of rental income to cover the second mortgage. Agree on the City doing more to support DADU and ADU construction, perhaps by waiving some or all of the permit charges, sewer connection fees, etc.

Gary Krause

Great Article. We have a decentralized model launching

in Q1 20/20 in Dallas TX. and

NCW-CW area. 😎😊👍

Jan Steinman

There is a third, which is long ignored, and which also has prohibitions† in most jurisdictions: home sharing.

Throughout 99% of human history, people have shared living space with more than just their immediate family. Sometimes it was multi-generational, but most of the time, it was at the tribe or clan level, meaning mostly-related, but also involving un-related individuals.

There are many reasons for this. It enables what Ivan Illich called “conviviality,” or the art of living together. When one lives with others outside their immediate family, they develop more tolerance of and appreciation for differences, they develop a greater sense of community, there is less crime, and they take care of each other, reducing pressure on already-strapped industrialized social support systems.

Not to mention that small houses are much less efficient on a per-capita basis than large houses. Five people in five bedrooms of a large house have a vastly reduced footprint than five people in five separate tiny houses! (Of course, apartments are a different matter.)

It was only when we started digging and pumping fossil sunlight out of the Earth that we had the wherewithal to not share housing beyond an immediate family.

There is a movement afoot to simplify this: co-housing. Co-housing complexes often share laundry and washrooms, and often feature a large communal dining area (supplemented by small kitchenettes in each unit), thus enabling conviviality while significantly reducing the per-capita ecological footprint — and cost!

We are working at providing this sort of solution, but we could use some help!

†The BC Residential Tenancy Act specifically excludes situations where tenants share a kitchen and bathroom with a landlord, thus, the rights of tenants in such situations are not protected by law, landlords must approve — and can deny — any subleases, or people sharing the rent, and an “unreasonable number of occupants” can result in lease termination.

Michael Andersen

Completely agreed!

Julia Minugh

It concerns me that I see new storage centers popping up in my community. Are they anticipating a need for space for belongings that won’t fit in the compact communities being built. Will new homes that may be less expensive, cause the savings to deminish by necessity to pay for storage space.

Julia Minugh

diminish

Julia Minugh

It concerns me that I see new storage centers popping up in my community. Are they anticipating a need for space for belongings that won’t fit in the compact communities being built. Will new homes that may be less expensive, cause the savings to diminish by necessity to pay for storage space.

Michael Andersen

Good point, Julia, and this concerns me, too—there’s a three-story storage center right next to the rail stop near my house and it drives me nuts that that isn’t either housing or the site for a meaningful number of jobs.

That said, I think there is actually a case for storage centers as a response to our ever-rising standards for new housing construction. Should we hold homes to an expensive but generally high-quality standard of construction? Maybe. You might see storage centers as essentially be a way to avoid holding our storage space to that same expensive standard, making the system more efficient overall.

Or maybe not, I’m not sure. That storage center near me is illegal in residential zones; they built it in a light industrial one. Somehow I suspect that wasn’t what some planner imagined when zoning that plot of land for light industry.

Chris S

The major assumption here is that a smaller home equals a cheaper home. Obviously, in absolute terms that is true. But has someone done the research to find out whether small units are proportionally less expensive, or just marginally so? Let’s take as an example the 12-plex in Portland (pictured above). The captions states that the most expensive of the units is 5% cheaper than the replaced single family house. Should the units be approximately 1/12 of the price of the single family home? Eh, well, maybe not 1/12 but they should be significantly cheaper, measured in times, not %. I have the suspicion that someone is making a wonderful profit out of this flip. I would applaud that if it was not at the expense of affordability.

Michael Andersen

Smaller homes do rent or sell for more per square foot, but they also cost more to build per square foot. Kitchens and bathrooms cost a lot more than family rooms and bedrooms.

As for the 12plex, of course a newly built home is more expensive per square foot than a 100-year-old one! But they aren’t actually that much smaller than the old one, it’s just that they’re newly built and there are 11 more of them. The efficiency of having more homes per lot is in the land cost, not in any of the other major costs. That (plus the smaller size) is the main reason they can be sold more cheaply and still pay for the time and risk of everybody involved.

Chris S

Yes, but condos share the roof and basement and foundation – this is a significant saving. My point is that while small units are less expensive they are by no means affordable. A small-ER new construction unit in Bellevue (I have not seen anything smaller than 1500 sq ft) is still over $ 1/2 million. That is far from being affordable.

Howard Metzenberg

The statistics fail to capture what really happens to a lot of this surplus family sized housing. Some of it is de facto subdivided into rooming houses, filled with residents without leases, in which there are sometimes more housemates than rooms.

Sometimes shared spaces such as living rooms are curtained off to add an extra resident. Bonus rooms such as dens, garages, basements, or even large closets, are rented out, although housing codes prohibit it.

My wife and I know of a number of cases of this amongst our extended networks of friends, including parents taking in adult children or adult children taking in parents. In some cases, is landlord is aware, and overlooks an arrangement that is technically illegal but is benefiting both parties.