Courtney Freeman met me this month at her front door, on which she’s hung a little wreath tied with a red ribbon. Then she led me past photos of her niece and nephew and into her little living room, where she offered me a bottle of water and started talking about sharing.

“I really worked my butt off and worked my way to being a homeowner,” said Freeman, a hospital health educator and mom who lives in Portland just east of Northeast 82nd Avenue. “I understand how it can be to go through the struggle. You don’t have it and you don’t have resources to get it. … I have walked that walk and know what it’s like to struggle and here I am, a homeowner.”

Meanwhile, she said, “we see the homelessness right before our eyes every day.”

The mismatch between her circumstance and those she sees around her is one thing that caught Freeman’s attention about a promising new plan in Portland: A program, now in development by the nonprofit Hacienda Community Development Corporation, that would build 537-square-foot cottages in the backyards of low- to middle-income homeowners, like Freeman. These modest cottages would provide regulated affordable housing for low-income tenants for 10 to 15 years. After that, the accessory cottage would revert to control of the property owner.

Hacienda calculates the program should be able to deliver homes at half the public cost of a more traditional below-market housing project.

That’s an audacious goal. But here’s the biggest mark in its favor: It’s making use of land that’s just sort of sitting around.

“I’ve got this huge backyard,” Freeman said. “And here could be someone else that’s coming from either a similar situation or a not so similar situation. But we both can relate to the struggle.”

“I looked at this as: here’s two people who can meet each other halfway and help each other,” Freeman said.

New twists on a fast-spreading idea

Rose Ojeda, real estate developer for Hacienda CDC, and Kate Allen, Hacienda’s consultant on the “Small Homes Northwest” pilot project. Photo by Michael Andersen, used with permission.

Hacienda’s concept isn’t entirely new. It’s just the latest local iteration of an increasingly common but frustratingly hard-to-execute idea: subsidizing construction of backyard cottages for scattered-site affordable housing.

For a few years, as privately funded ADUs have surged in popularity, nonprofit entrepreneurs around the United States have been chasing this concept with the tenacity of Thomas Edison, twisting filaments and reshaping glass in search of the light bulb they’re convinced is waiting to be invented.

My colleague Margaret Morales wrote last year about five of these programs, including an earlier pilot spearheaded by Portland’s Multnomah County that had focused on housing recently homeless people. That one, like Hacienda’s, was backed by the Oregon charitable foundation Meyer Memorial Trust. It ended up creating four such homes but stalled amid permitting delays, an unexpected tax liability and a decision by county leaders to pay above-market wages to workers on the project.

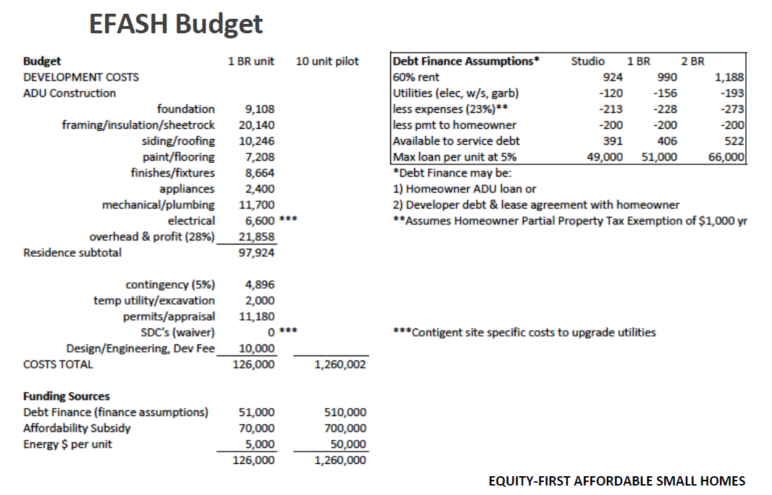

So far, Hacienda’s run at this concept exists only on paper. But it’s different from the county’s in various ways. The community-based nonprofit is specifically targeting lower-income homeowners to receive the ADUs, and building in a modest monthly income for the homeowner—maybe $200 out of a $990 per month rent payment. The program would recruit homeowners through partnerships with culturally or geographically specific nonprofits: Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, Verde, ROSE Community Development. (Freeman, for example, got wind of the program in part because Verde happened to help her build her rain garden.) Construction of each mostly-uniform 24-by-24 ADU would be done at market wages through a partnership with the National Association of Minority Contractors, by companies that lack the scale to tackle big commercial projects.

And, crucially, the homes are being privately financed by customized loans from a lender such as Craft3, Umpqua Bank or Consolidated Community Credit Union, with Hacienda serving as the homeowner’s advocate and financial counselor. After that, a seasoned property manager—PCRI or ROSE—will join the team to collect rent and start cutting monthly checks to landlord and lender.

That property management deal is a key factor in recruiting homeowners and persuading a lender that they can count on a steady flow of rent payments.

“A barrier to a lot of homeowners is ‘I don’t want to be a landlord,'” explained Kate Allen, a Hacienda consultant who’s co-creating the program with Rose Ojeda, Hacienda’s in-house real estate developer.

The pair are so bullish about their business plan that they’ve given it an ambitiously generic name: “Small Homes Northwest.”

For the moment, the program’s only subsidy is coming from Meyer Memorial Trust, but the goal is to eventually persuade the state or local governments to open a revenue stream that doesn’t add much paperwork: a tax abatement option or a simple, targeted grant.

If the cost estimates actually work, they think they’ll have a strong argument to make.

The Portland Housing Bureau’s usual subsidy for a newly created below-market home, Ojeda said, is $150,000 per unit.

“We’re asking for $66,000,” she said.

Simple backyard cottages are hard to finance. But they’re really not very expensive to build.

“The land is already owned,” explained Allen. “The utilities are already in.”

“The real question is: Can you make it replicable?”

A rough development budget for Hacienda’s affordable-ADU pilot. Courtesy of Hacienda Community Development Corporation.

Michael Parkhurst, a housing program officer at Meyer Memorial Trust who’s been part of funding the program’s development, said he doesn’t assume everything will go as planned.

“For me it’s important to realize that it’s a pilot effort,” he said. “We’ll see how some of these things work out.”

But Parkhurst said Meyer is excited about this pilot because of the strength of the project team and the fact that “they’re trying to think creatively around multiple challenges at the same time”—housing stability, wealth building, economic development and plain old housing supply.

“I guess the real question is: Can you make it replicable, so you can start doing significant numbers on an ongoing basis and keep going?” Parkhurst said.

If the first handful of homes can be built as planned, he imagines finding state or local funding that could potentially allow hundreds of such projects in the target neighborhoods: investment without displacement.

“That’s a place where you’re having some real tangible benefit,” he said. “That starts to feel like you’re supporting a community.”

Freeman, who bought her house four years ago—and who often looks after her young niece and nephew, in addition to her own two-year-old, because their mother is also a single mom—looks forward to building community around the home she’s worked so hard to have.

“That’s what I think homeownership is about,” she said. Freeman said her mother owns a home in Northeast Portland’s Sabin neighborhood, four miles to the west on the edge of Portland’s formerly redlined and majority-Black area. Today, the median home there costs $575,000, according to Zillow.

“It was not the neighborhood it is now, but it changed, and it changed so much for the better,” Freeman said. “This neighborhood, as well as any other neighborhood, could potentially be that in the future.”

Tim McCormick

this is a great program — Equity First Affordable Small Homes. The current targets, I heard at Sept presentation at Meyer Trust, are homeowner household at 100% area mean income or below, tenant < 60% AMI. It seems this is exactly the type of exploratory project we should publicly fund with, for example, the $45M still unallocated from the Portland Housing Bond which has already met all its goals.

Another, more radical Affordable ADU model was proposed for same Meyer grant program, by a team I led from Portland Village Coalition. It aims to serve low-income homeowners & extremely low-income (ELI) ADU residents, using very low-cost movable and *ownable* small houses. See: New Starter Homes.

This proposed program uses Oregon’s new Small House Specialty Code; simple screw/post, standardized, subsurface foundations, & RV-type utility connectors, so the foundation is low-cost & easy to build, allows ADU to relocate/change, & means the homeowner need not permanently commit to hosting an ADU. With this approach, subsidy is focused on the most in-need homeowners & small-house dwellers, the arrangement can be flexible for all parties, and it builds equity + agency for wider range of residents, rather than just permanent equity for a comparatively well-off homeowner.

Also, this model is oriented to off-grid, post-disaster / climate-change adaptative, eco housing. Various & existing small houses could be used, or built off-site efficiently; foundations could be pre-laid + covered, or easily added in many places eg public land, parking lots.

Finally, Portland could quickly create a simple version of this low-cost model by allowing tiny houses on wheels as ADUs, as Los Angeles did this week (!); and as PDX Planning Commissioner Eli Spevak proposed a few years ago.

Joe Missionary

I would like to share my experiences living adjacent to two of Hacienda’s properties for ten years in the Cully neighborhood. Directly behind my house was the Clara Vista Townhouses. The tenants living there frequently threw trash and beer cans into by backyard from their balconies. One morning after a late and and loud party in one of the townhouses, I found approximately twenty beer bottles had been thrown over my chain link fence. That same fence was torn down and three stolen bicycles were hidden in my backyard behind blackberry bushes. These are just a few of examples of the lack of respect shown to me by the tenants of this property. Just one hundred yards east of my house and across Cully Blvd. was the Villa de Clara Vista complex. Due to a lack of off street parking at that location, many of the tenants would park on across Cully Blvd on Emerson Street in front of my house where I would frequently see them throw their fast food trash and even dirty diapers in the street before walking across Cully Blvd to their apartments. I confirmed these thoughtless individuals were tenants of the the Villa de Clara apartments by following them and watching them use a key to open the front door of the apartments. For many years on the evening before putting my garbage can on the street, I would take a kitchen sized trash bags and not only pick up the trash in front on my house in the street; I would cross Cully Blvd and pick up trash in the street in front of the Villa de Clara Vista apartments. It did not take too long to fill that bag up. I was motivated to clean up the street because I always thought that I would never sell my house and I wanted to help keep my neighborhood clean. Some of the residents of the Villa de Clara Vista apartments would work on their cars on Emerson street, drain fluids directly on the street and leave car parts in the street such a batteries, water pumps and spark plugs. The response to my complaints to the management of these apartments was, “ Oh no, it is not my tenants working on those cars or throw trash on the street.” This email is not a personal attack on any ethic group, but an example of the extreme neglect of the Hacienda group and their management representatives in requiring their tenants to be good neighbors.