For years, three-quarters of Portland’s residential land has been almost entirely off-limits to anyone—a nonprofit developer, a government agency, anyone—who wants to build new guaranteed-affordable housing.

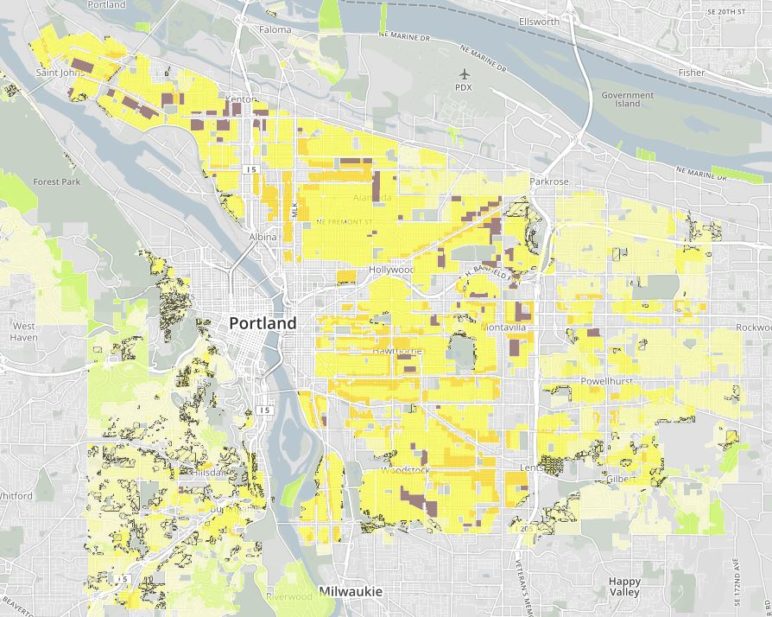

These no-go zones for affordable-housing projects are marked in yellow, orange, brown and light green in the map below.

Cascadia’s third-largest city has plenty of affordable housing developers: Habitat for Humanity, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, Catholic Charities and a cluster of community development corporations: Hacienda, ROSE, REACH. But because of Portland’s laws, none of them are building in the areas marked above.

Why on earth would a city, especially one suffering from a widely acknowledged crisis in the price of housing, do this to itself?

The reason is simple: That’s a map of Portland’s low-density residential zones, from which the city mostly banned duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes in 1959.

In areas where Portland prevented the private sector from building the sort of urban homes that people in the middle class can afford, it also prevented the public sector from building the sort of homes poor people can afford. As Portland has prospered economically and space in the city has become more precious, this obstacle has loomed larger and larger.

But what if the city were to change that?

What if Portland were to not only re-legalize market-rate fourplexes affordable to the middle class (a public-school teacher, a bartender, a firefighter) but also create an option specifically intended to create below-market homes immediately affordable to poorer folks like a home-health aide, a day-care provider or a fixed-income retiree?

Building bigger means building cheaper

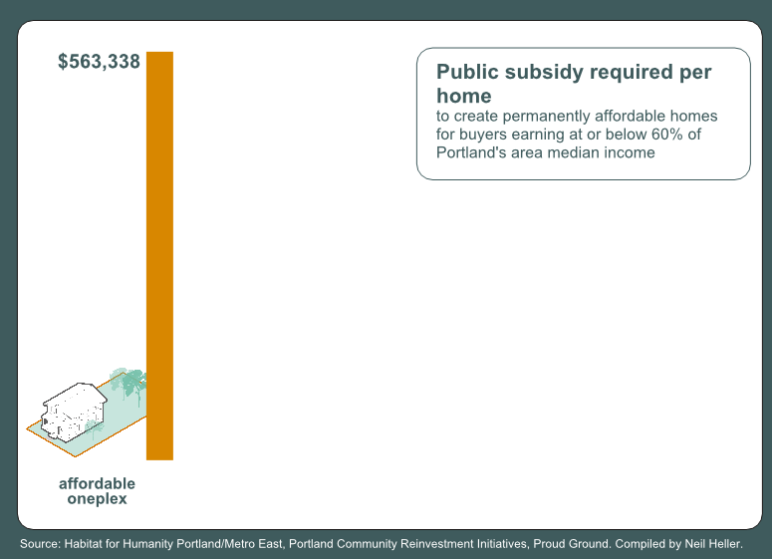

These days, for almost anyone trying to build the sort of subsidized homes that’d be affordable to truly low-income Portlanders, the costs in low-density zones are essentially insurmountable. Creating a fairly average-size detached home—1,600 square feet—in a close-in neighborhood like Portland’s Brooklyn area would cost $300,000 just for the land, because any buildable lot would almost certainly already contain an old house. Then it’d cost another $479,000 to develop, build and sell.

If you wanted to subsidize that project until the related mortgage and utility payments were affordable to a family making 60 percent of median income, the public would need to cover 72 percent of the cost of that home: $563,338.

Simply put: With thousands of Portlanders in desperate need of better housing, this would not be a very good use of public money. This is far more than the $167,000 per home created or preserved by the Portland region’s recent housing bond—spending this much to house one household would mean failing to serve two or three others.

Simply put: With thousands of Portlanders in desperate need of better housing, this would not be a very good use of public money. This is far more than the $167,000 per home created or preserved by the Portland region’s recent housing bond—spending this much to house one household would mean failing to serve two or three others.

That’s why nobody in Portland is building below-market oneplexes—and that’s why below-market housing development has been essentially banned from most of the area in the map above, where oneplexes are the only legal option.

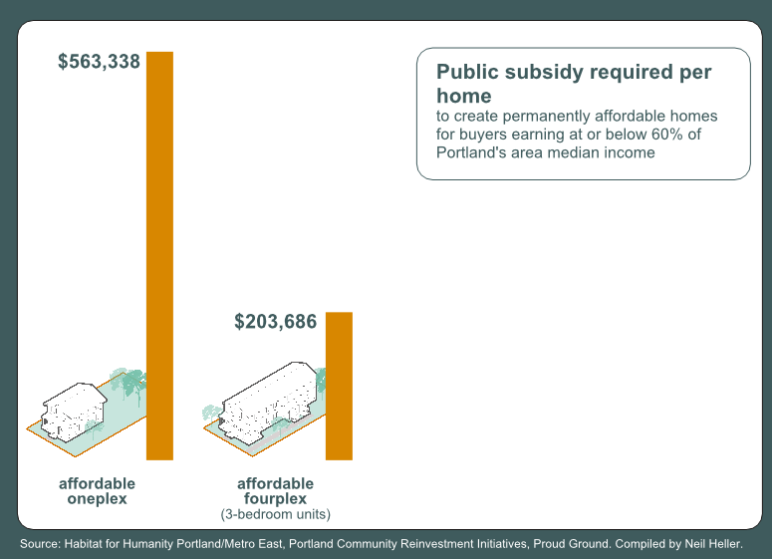

But what if fourplexes were an option?

It turns out that for the same reason that market-rate fourplexes tend to be cheaper than market-rate oneplexes, duplexes or triplexes, below-market fourplexes require less subsidy than below-market oneplexes, duplexes or triplexes.

Not only does an affordable housing developer like Habitat for Humanity get to split the land cost four ways, they also spread the costs of condoization and site preparation. This is the result:

Portland’s affordable housing developers have been pointing this out for years. It’s why they endorsed state-level legalization of market-rate fourplexes last spring—because, as they pointed out, the rules would let nonprofit builders house far more Portlanders below the market rate, too.

Portland’s affordable housing developers have been pointing this out for years. It’s why they endorsed state-level legalization of market-rate fourplexes last spring—because, as they pointed out, the rules would let nonprofit builders house far more Portlanders below the market rate, too.

But a $200,000 subsidy per home is still a lot of money—more than most housing nonprofits can find under most circumstances.

That leads to an interesting question.

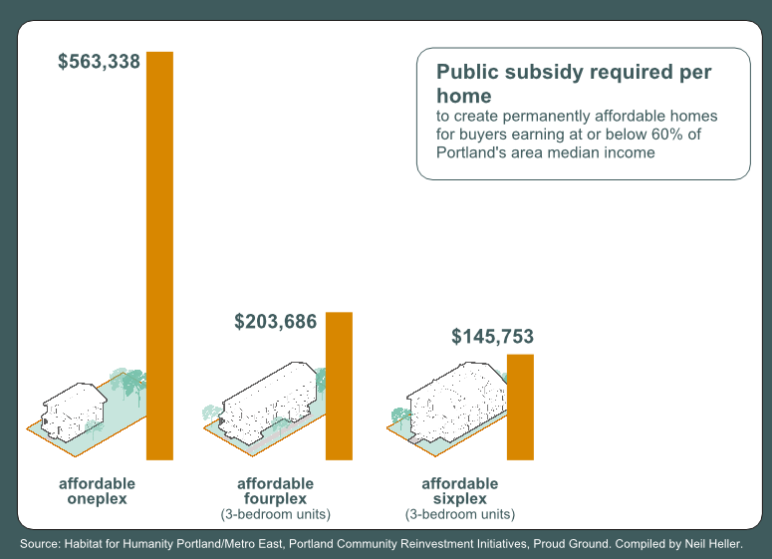

What if, in Portland’s search for ways to create below-market housing in areas near the best transit, schools and jobs, it’s been thinking … too small?

For the last few months, a pair of Portland housing advocates, Neil Heller and Madeline Kovacs, have taken on a volunteer project to find out just how low that orange bar can go. Kovacs, a Sightline outreach associate and a co-founder of the advocacy group Portland: Neighbors Welcome connected Heller, a Portland-based faculty member of the Incremental Development Alliance, with nonprofit developers at Habitat for Humanity Portland/Metro East, the local community land trust Proud Ground, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives and ROSE Community Development Corporation.

Using the cost figures and regulatory constraints provided by those nonprofits, Heller ran the numbers on what it might cost those nonprofits to build more deeply affordable homes in bigger buildings, if only the city let them.

According to the figures, it helps quite a lot. Allowing three-story sixplexes, with each home an 1,100 square foot three-bedroom, would reduce the public subsidy per unit by another 28 percent.

This brings the figure below the magic number of $150,000 that the Portland Housing Bureau sets as its maximum subsidy for new below-market homes.

This brings the figure below the magic number of $150,000 that the Portland Housing Bureau sets as its maximum subsidy for new below-market homes.

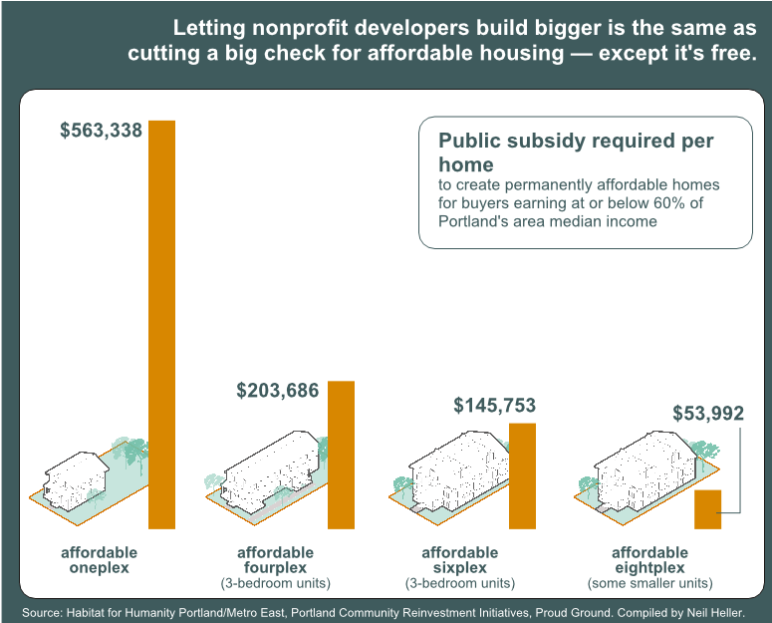

Using the same building size, there’s another option too: we could allow some of the homes to be smaller (still including one family-size home, but bringing the average unit size down to 800 square feet). This would let the project divide its costs eight ways and also (because of the smaller sizes) sharply reduce construction cost per home.

This combination brings the per-unit subsidy significantly lower.

For any of these examples except the last, a would-be homebuyer earning up to 60 percent of Portland’s median income would be taking out the same mortgage: $282,597 before down payment assistance of up to $80,000 per home.

For any of these examples except the last, a would-be homebuyer earning up to 60 percent of Portland’s median income would be taking out the same mortgage: $282,597 before down payment assistance of up to $80,000 per home.

At current interest rates, that’d come to a monthly mortgage payment of $1,390 per month for one of these three-bedroom homes in an inner Portland neighborhood.

(In the case of the eightplex, the buyer’s price would be lower for the smaller homes.)

In other words: A “deeper affordability” option would make public dollars far more efficient—and every project could house many more people.

“The cool thing is that zoning changes are technically free,” Heller said in an interview.

A potential homeownership lifeline for less wealthy Portlanders

Cecelia, a homebuyer at Cully Place, at a home dedication last summer. The 15-unit community land trust project is being developed and built by Habitat for Humanity in one of the few parts of Portland that currently allows that density of housing. The homes will remain permanently affordable thanks to a unique partnership with Proud Ground. Photo by Habitat for Humanity Portland Metro/East, used with permission.

Steve Messinetti, the local Habitat CEO, said his organization is strongly in favor of a “deeper affordability” option in the residential infill project.

“The key thing for us and for others is that if we’re serious about addressing the minority homeownership gap, we need to be looking for ways to serve under-60-percent households,” Messinetti said, referring to Portlanders making less than 60 percent of the median income.

In Portland as of 2017, the median household brings in $58,423 per year, but the median Black household has an income of $26,675, the median Native American household $29,859 and the median Latino household $40,982.

“All affordable housing currently needs more than $100,000 in subsidy to work,” Messinetti said. “If we can get that subsidy down, our dollars that go to that are going to go a lot further. … We’re doing a project in Northeast [Portland] right now where we’re doing $125,000 in city subsidy per door to make it work. If we only needed $60,000, we could have built twice as many homes.”

Three-quarters of local Habitat homebuyers are people of color, and most are earning 30 to 50 percent of the area’s median income, so currently as little as $23,760 for a family of three. (In Portland, that’s one full-time job at minimum wage.) Habitat could take advantage of the deeper affordability option while making homeownership projects affordable to that family thanks to help from volunteers and private subsidies.

“The other option is that people are continuing to move further and further out and continuing to see the problems that we’ve seen with traffic and the cost of living,” Messinetti said. “Quality of life is getting worse and worse because the people who run our city are not able to afford to live in it.”

Hundreds of potential new affordable rentals in inner Southeast Portland alone

According to Heller’s numbers, the “deeper affordability” sixplex-eightplex option wouldn’t be any more viable than the fourplex option for most nonprofits that specialize in below-market rentals, like East Portland’s ROSE CDC. That’s because so much the cost of rentals is caught up in their maintenance and operation.

(Fourplexes, sixplexes and eighplexes would all be far more viable than oneplexes, though.)

But there is one organization in Portland that specializes in rental housing and could gradually deliver huge results from the “deeper affordabilty” option: REACH CDC, ROSE’s peer organization that works in inner Southeast Portland.

That’s because, unlike most developers, REACH doesn’t have to acquire new land. It already owns, operates and subsidizes 60 low-density properties in inner Southeast Portland, acquired decades ago when the area’s biggest housing problem was disinvestment.

“The price of land in really good transit-oriented sites is getting so expensive,” said Dan Valliere, REACH’s CEO. A “deeper affordability” option in Portland’s residential infill project, he said, would “create some opportunities over time for REACH to redevelop those in a slightly more dense way.”

Beyond that, Valliere said, REACH’s residents get another huge benefit from affordable homeownership programs: it gives them somewhere to move to.

“Every year there are people who live in a REACH rental who end up leaving because they’re buying a home,” Valliere said. “That’s not everybody’s goal; there are many many other REACH renters whose goal is to live out their life there, and that’s great.”

But for those who do want to buy, there are few options near their longtime home.

“One of the big problems right now is finding a place,” Valliere said. “People can get organized, they have a little down payment even, they have a steady income. They live in affordable housing, which allows them to save, but they still struggle to find a place. … So my only choice is to move 80 miles away?“

“This could be a really helpful thing for residents at REACH, those who are saving for a home,” Valliere said.

The equivalent of cutting a $150,000 check to every new affordable home

New Columbia in Portland’s Portsmouth neighborhood, managed by Home Forward, is Oregon’s largest mixed-income development. It consists largely of fourplexes, sixplexes and eightplexes for a good reason: They make public dollars go a long way. Image courtesy of Google Maps.

Last month, Portland’s city council approved a different reform to mid-density zones, called Better Housing by Design, that will allow mixed-income rentals in many more areas.

Unlike the residential infill project, which is projected to reduce demolition-related displacement of low-income renters, that reform was projected to increase it.

But Portland’s progressive housing community supported the Better Housing by Design reform anyway, largely because it included generous provisions for a “deeper affordability” option—letting buildings be twice as big if at least half the homes inside were affordable at 60 percent of median income.

But Portland’s reform to its low-density zones has never had such a provision, essentially because of a perception that it would be politically impossible to allow three-story sixplexes or eightplexes on some properties in Portland’s longtime no-go zone for affordable housing.

Even if doing so were (compared to the current fourplex option) the financial equivalent of cutting a check for $150,000 to every single one of those new homes, at zero additional cost to the public.

The work of housing advocates like Heller calls that perception into question. If Portland wants to gradually create hundreds of homes in low-density zones that are immediately and permanently affordable to low-income people without vastly increasing its housing budget, he thinks this is how.

Portland: Neighbors Welcome, the group Heller and Kovacs volunteer for (full disclosure: I do, too) is mobilizing Portlanders to testify in support of this proposal, both in person and online. The hearing is next week.

“We didn’t pre-negotiate ourselves based on fear of what’s palatable,” Heller said. “I think there’s some value in just objectively saying, ‘What does it take?’ Do the math and understand it from there.”

Tim McCormick

It sounds good to me, though I wonder about the political calculus. Portland’s Residential Infill Program, in current form allowing four-plexes, after four years of whittling and epic public process, and limiting new buildings essentially to current scale of houses, is in question of passing at city council. If expanded to allow 6 or 8plexes, what would its trajectory be then?

The article’s premise that most of Portland now, ie single-family housing zones, is off-limits to guaranteed-affordable housing, seems refuted by, for example, Hacienda CDC et al’s EFASH (Equity First Affordable Small Homes) ADU program which Andersem wrote about a few weeks ago.

In the best-case, 8-plex scenario described in current article, a $54k/unit local subsidy is required to create ownable (i.e. condo) unit needing $1390/mo mortgage + $80k downpayment (I think?) + I think Low-Income Housing Tax Credit or other financing layer(s) from the non-profit. We might instead for $54k buy people a tiny house outright, arrange siting on a low-income homeowners’ lot for probably less than $500/mo, and thereby create affordability for both the cottage resident and the primary homeowner.

At least as a comparative exercise, we can and in my view should try to think from the bottom up: what soonest could help the poorest, for the least cost / most people? I’m guessing many an unhoused person, like me would choose a tiny house which they could own now and later relocate to where they want it, over an apt/condo on a $1390/mo 20+ year mortgage, even if that were a significantly bigger apartment. Also, they can’t get that mortgage, so probably this someday never comes.

—

Tim McCormick

HousingWiki, Village Collaborative

Portland

R. John Anderson

Neil Heller is taking a straightforward approach, asking “What does it take? Do the math and understand it from there.”

Portland politics often operate in a magical realm immune to the constraints of basic housing and infrastructure math. With all of Portland’s most productive affordable housing operators advocating for this modest common sense proposal, I wonder what the response of the commissioners will be? I can imagine a couple possible reactions:

1.). I can’t do the math, so we can’t change our arbitrary exclusionary zoning.

2.). I can do the math, but I don’t want to upset people speculating on one unit housing.

3.). More housing choices and greater fiscal responsibility? Let’s do this.

david brown

What about infrastructure impacts to water and sewer created by the increased density? Aren’t these like 20 year decisions that will take a big investment by the city to mitigate? What about traffic and parking issues created by the increased density? What about existing home owners that want their single home neighborhoods? What happens to the value of their investment when you fundamentally change the neighborhood? What about increases to crime and a degraded livability when you start cramming people closer and closer together?

Michael Andersen

Good question about water and sewer, David!

As potentially exciting as this is, it would take many years to build even a few thousand projects like this. In a city of 650,000, that’s a drop in the bucket (or the toilet). A few buildings that have six or eight homes, instead of three or four as currently proposed, aren’t going to make a substantial difference, especially because population density in Portland is (like our peer cities) falling over the long term. Falling household sizes mean our low-density areas have fewer people (and therefore fewer poops) per square mile than they did in the 60s.

On traffic: As Messinetti says, the alternative to affordable housing in Portland is people driving in from miles away every day. Compared to homes on the suburban fringe (or even in like Aloha or Gresham), these potential homes already have better transit access, and that access stands to improve further if ridership in the area goes up. (Similar story with biking.) But low-density housing is gonna create more cars almost every time, even for people who are quite poor. Infill isn’t a cause of traffic problems — it’s the only way out of them. For regulated-affordable infill that goes double.

Amy Anderson

I would be thrilled to have a 3 bedroom townhouse /s built on my 100 ft lot, i however need a developer to make my land accommodating

david brown

The facts don’t support that in-fill will solve traffic problems. One example is the new apartment houses in Portland that are built without parking thinking that because they are close to a light rail line people would chose to not have a car. Guess what didn’t pan out as now the fight over on street parking spaces are now in full swing? Bikes are still less than 5% of commuters and frankly without a major (as in billions) increase in biking infrastructure that is not going to change much. The if you build it they will come crowd was wrong and there is no reason (or facts supporting any other conclusion) that is going to change. Even when Portland makes it so hard to travel by car people still want to travel by car. And not everyone wants to go downtown which is pretty much the only destination that is well served by mass transit. Also, jobs change and sometimes change locations. It is much harder to change where you live.

mh

Start charging directly for on-street parking, and all kinds of magic happen.

KR

Oh yeah, taxing people to death is always the solution. People aren’t going to give up their cars. They will simply leave when life becomes too difficult and expensive in the area to make it worth their while to live there. If our city planners would deal with reality, they would legislate mandatory parking for one to two cars in every unit they build.

Niles McGiver

This RIP, and this options is all good and dandy, but we also now really need the ability for people to own these units. We need people to be able to buy/sell a share % of home without the whole group having to refinance. Other states have fractional mortgages (CA and NY) where you can more easily do this, but rates are usually slightly higher (which is also ridiculous). FM could help middle class people buy homes in a home w an ADU, or a 3-8 plex. So far as I can tell that we don’t have this option is because banks don’t like anything that gets in the way of maximum profit, and maximum flexibility when it comes to repossessing a home. or challenges them to think in a new way (they are slow moving dinosaurs). We also need to make it easier for existing properties to convert to condo-associations, or create separate category (micro-condo association?) legislation that makes it cheaper and quicker to create condo association for developments of 2-8 units. It can cost > $20k on top of building and permitting fees to do this. Allowing these things would help preserve existing buildings like those big victorians no one but a doctor/lawyer in NW can afford.It would allow them to be segmented into functional and affordable pieces. It would also make it possible for people in Portland to own some of these newer developments (rather than just renting).

KR

Hey Niles, how about allowing Portland to carve up all the empty commercial property and turn it into housing? Think the empty Sears and K-Mart stores, empty Office Depot and Staples stores, and dead malls? I would much rather see that, than see single family homes demolished to be replaced by skinny apartments with no garages to park cars. There is always adequate parking in front of these big box stores and malls, too.

K Walker

I would be surprised if you could regulate your way to limiting these proposals to “affordable housing developers” or regulate how much the developers or subsequent owners can charge for a residence, especially after the initial build. When applied on a large scale like proposed, it seems ripe for being found unconstitutional or likely for the development lobby to eradicate any income restrictions. And if that fails, then any developer can knock down a house in any neighborhood and build a multi-plex without parking and charge what they want.

Your map is intentionally deceptive – everything you can’t build on is in color. Just show a map of the areas you CAN build 3-4 units per structure and 6-8 units per structure in PDX. There are many areas you can already do this in. If in fact, you are talking about realistically building a few thousand of these, then why not determine specific locations and go through the zone change process for those areas, rather than trying to make this happen anywhere or everywhere and anytime?

Please require multi-units to have parking. The “affordable housing” residents will have cars, jobs and many with kids. Charging them and the surrounding homes (many already without off-street parking) as you propose above, does not lead them to give up their cars. You have to be well off, unemployed, without kids, not disabled, and/or with good rain gear to get along well without access to a car in Portland. It just makes it less livable and more frustrating to have to drive around, lurking to find a parking spot, and walk blocks back to your home schlepping kids, groceries, etc. (often in the rain).

Michael Andersen

We regulate the price of homes all the time — the Pearl District has thousands of privately financed homes that are regulated to be affordable. Almost every new apartment building permitted in the last three years has a share of on-site homes that are regulated to be affordable. The city has had affordability incentives built into its fees and taxes for many years.

With homeownership projects, the best way to guarantee permanent affordability is with a community land trust, as discussed above. I’m a big fan of this model that combines some of the advantages of homeownership with some of the advantages of renting. You can read more from my colleague Nisma here:

https://www.sightline.org/2019/09/25/the-role-of-community-land-trusts-in-cascadias-quest-for-affordable-housing/