The news from southern Oregon looks promising: There is growing evidence that the Jordan Cove LNG export project will run aground, sharing the same fate as every other major Northwest fossil fuel project over the last decade. When the project backer, Pembina, withdrew its permit application from the Oregon Department of State Lands in late January, many heralded the scheme’s demise. But Jordan Cove has returned, zombie-like, several times before—and this time may be no different. Some observers believe that Pembina may try to get approval from federal regulators and then resubmit its application to state level after the Trump Administration weakens key provisions in the US Clean Water Act, potentially forcing a showdown over whether federal water laws can preempt state authority.

The fight over Jordan Cove is emblematic of Northwest’s long-running opposition movement to coal, oil, and gas export projects that Sightline calls the thin green line. For a decade, Cascadians have opposed carbon fuel proposals in unprecedented numbers, repeatedly packing local hearing rooms to standing-room-only, burying government agencies with hundreds of thousands of comment letters, and committing scores of acts of civil disobedience. The movement has even spawned its own art.

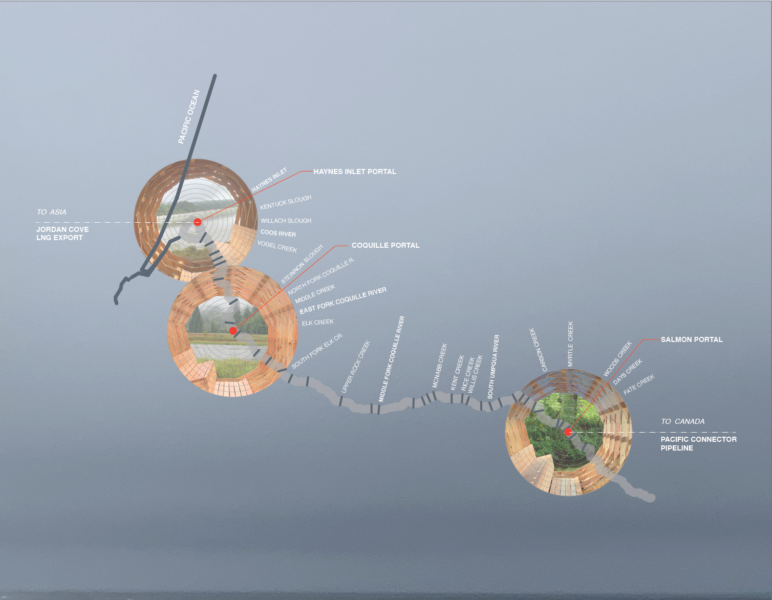

At the University of Oregon, Erin Moore’s architectural design studio made one contribution in 2016 with “Lines, Pipelines, and the Contested Space of Fossil Fuel Transport in the Pacific Northwest,” which reimagined fossil fuel export schemes. Now, a new project from Moore looks hard at the route of the Pacific Connector Pipeline that would supply gas to the Jordan Cove site on Coos Bay. She designed and built a trio of pavilions along the proposed route, each one highlighting the natural features of its site and encouraging visitors to imagine a different use of southern Oregon’s landscapes.

As the project website describes it:

Each of the three pavilions is constructed on private land owned by community members who are actively challenging the expropriation of their land for pipeline construction. Each of the sites is ecologically rich—one is estuarian, one is wetland, one is riparian. Each of the three resisting landowners have stewarded their land for biodiversity conservation. The Portals are intended as direct action pipeline resistance.

The planned 36-inch diameter Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline would run across 229 miles of public and private land from a pipeline hub in south-central Oregon to the coastal site of the facility. The proposed route would cross the traditional territories of the Klamath, Yurok, and Karuk Tribes who argue that it would disturb sacred sites, burial grounds, and other cultural resources.

The pipeline would stretch across the remoted and rugged forests of southern Oregon. Along the way it would cross 485 wetlands and waterways, including some of the Northwest’s most prized streams, including big rivers like the Rogue and the Klamath, as well as smaller ones like the South Umpqua, and the north and east forks of the Coquille. All of these are federally recognized for their pristine habitat or cultural value, and 74 are home to fish. Conservationists worry that the pipeline would harm critical runs of salmon and steelhead.

Not surprisingly, the Jordan Cove project faces opposition all along the pipeline’s route. Over 500 landowners would be directly impacted, many by eminent domain proceedings in which the government would seize a portion of their land for the private use of Pembina’s pipeline. Many of these landowners have been vocal critics of the project, even getting arrested for their demonstrations.

If it is built, Jordan Cove will become Oregon’s single biggest source of carbon emissions, and that’s counting only the operations on site to liquefy the gas for export. Factoring in the staggering emissions of actually burning the gas for power at its destination—as well as the insidious leakage of methane from frack wells, compressor stations, and pipelines—the project is nothing short of climate disaster. In fact, a complete tally of the project’s carbon pollution might show that it is equivalent to fully one third or more of all the emissions in the entire state of Oregon.

The Northwest is at a crossroads, literally and figuratively. Confronted with a choice to become a carbon export hub of global proportions, the region has decided to chart a different course, one that prizes clean energy and climate responsibility. It’s time to ask how we will imagine a new future for the region, and what will it look like?

Thanks to Zane Gustafson, who provided research assistance.

Al Dopa

Thank you for the information. I would like to be updated about the progress, or, hopefully, abandonment, of this pipeline project.

Please let me know about any actions to participate in as well.

Thank you for your work!