Alaska is a cautionary tale. For those looking to understand the risks of hitching an economy to fossil fuels—and for those trying to determine how to manage a transition away from dirty energy—it’s instructive to examine the fiscal meltdown happening in the north.

Economic fallout from COVID-19 is lacerating government budgets across North America, but few places are bleeding red ink as profusely as the Last Frontier. The state’s heavy reliance on oil sales for revenue has left it uniquely exposed to recent energy market shocks that are exacerbating long-standing structural problems with the state budget.

Even before the pandemic hit, Alaska politics were consumed with arguments about how to deal with the state’s long-declining oil revenues.

Even before the pandemic hit, Alaska politics were consumed with arguments about how to deal with the state’s long-declining oil revenues. In January 2020 Alaska lawmakers were staring at a $1.5 billion deficit (roughly an 18 percent shortfall) in the year’s proposed budget. Now the ravages of the coronavirus have blown the deficit up by another $300 million in 2020 and potentially $600 million in 2021.

Understanding why Alaska faces such a dire situation in 2020 and what lawmakers can do to fix the situation requires looking at what caused the problem in the first place.

Alaska boasts vast mineral resources, including crude oil, but very few people live in the state. Less populous than Snohomish County, Washington, it was not long ago that it looked like oil wealth would be a blessing for Alaska’s economy. Now those resources have begun to seem more like a curse.

Alaskan oil production entered the big leagues of global energy markets in 1968, with the discovery of the largest oilfield in North America. The area around Prudhoe Bay was estimated at the time to hold 9.6 billion barrels of oil. Alaska’s then governor Bill Egan understood that the find would change Alaska’s future, saying in a 1970, “Alaska has become established as America’s greatest oil province. Ponder for a moment the promise, the dream, and the touch of destiny.”

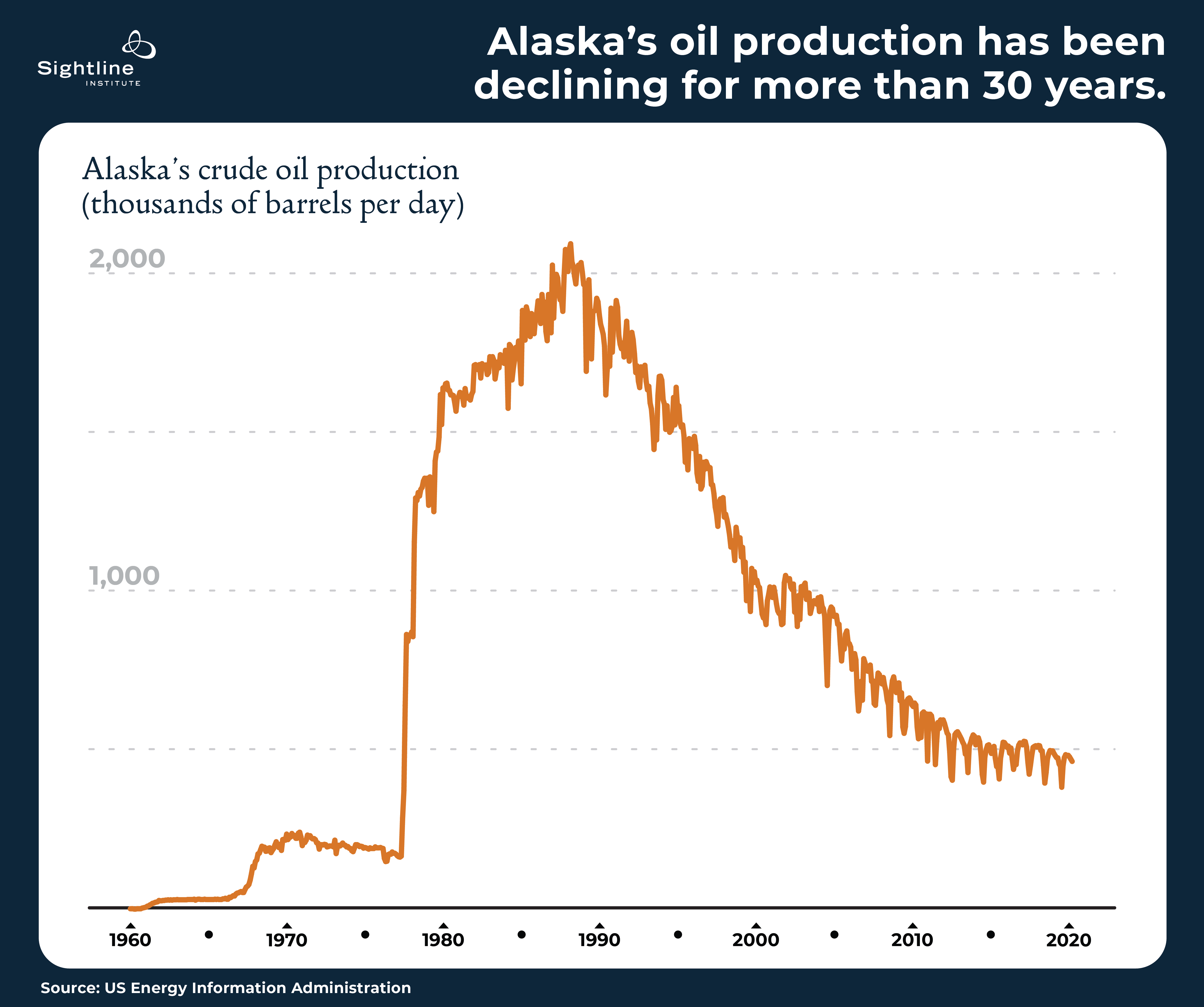

Initial oil production lived up to Egan’s expectations. By 1981, production at the North Slope reached 1.5 million barrels per day and eventually peaked at more than 2 million barrels per day in March 1988. The oil was indisputably was a boon to Alaska finances. Throughout the 1980s, revenue from taxes on oil production regularly accounted for 80-90 percent of Alaska’s total unrestricted general fund.

But after it peaked in 1988, oil production at the North Slope began a long, steady decline. In 1995 production dipped below 1.5 million barrels per day; and March 2002 was the last time production was above 1 million barrels per day. The highest production month of the 2010s was March 2010, when drillers managed to extract 636,000 barrels per day. Thus far in 2020, production has been steady at around 460,000 barrels per day—less than a quarter of what it was two decades ago.

Alaska fiances: Crude oil production is in decline. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

From the very beginning, most Alaskans understood that the oil would not last forever and therefore voted to create the Alaska Permanent Fund in 1976, a move designed to endow the state with a strong fiscal foundation. The enabling legislation stipulates that at least 25 percent of “all mineral lease rentals, royalties, royalty sale proceeds, federal mineral revenue sharing payments and bonuses received” by the state government would be deposited into the fund. These deposits, worth about $45 billion, compose the fund’s principal, which the legislature cannot spend for any reason. (Its function is similar to that of a university endowment.) The fund also includes about $17 billion of investment earnings. The amount in this Earnings Reserve Account can be spent by the legislature, which has famously chosen to give a significant portion of investment earnings from the fund back to Alaskans in the form of an annual Permanent Fund Dividend. The dividend usually pays out between $900 and $1,900 per person. In 2020 the per capita dividend was set at $992.

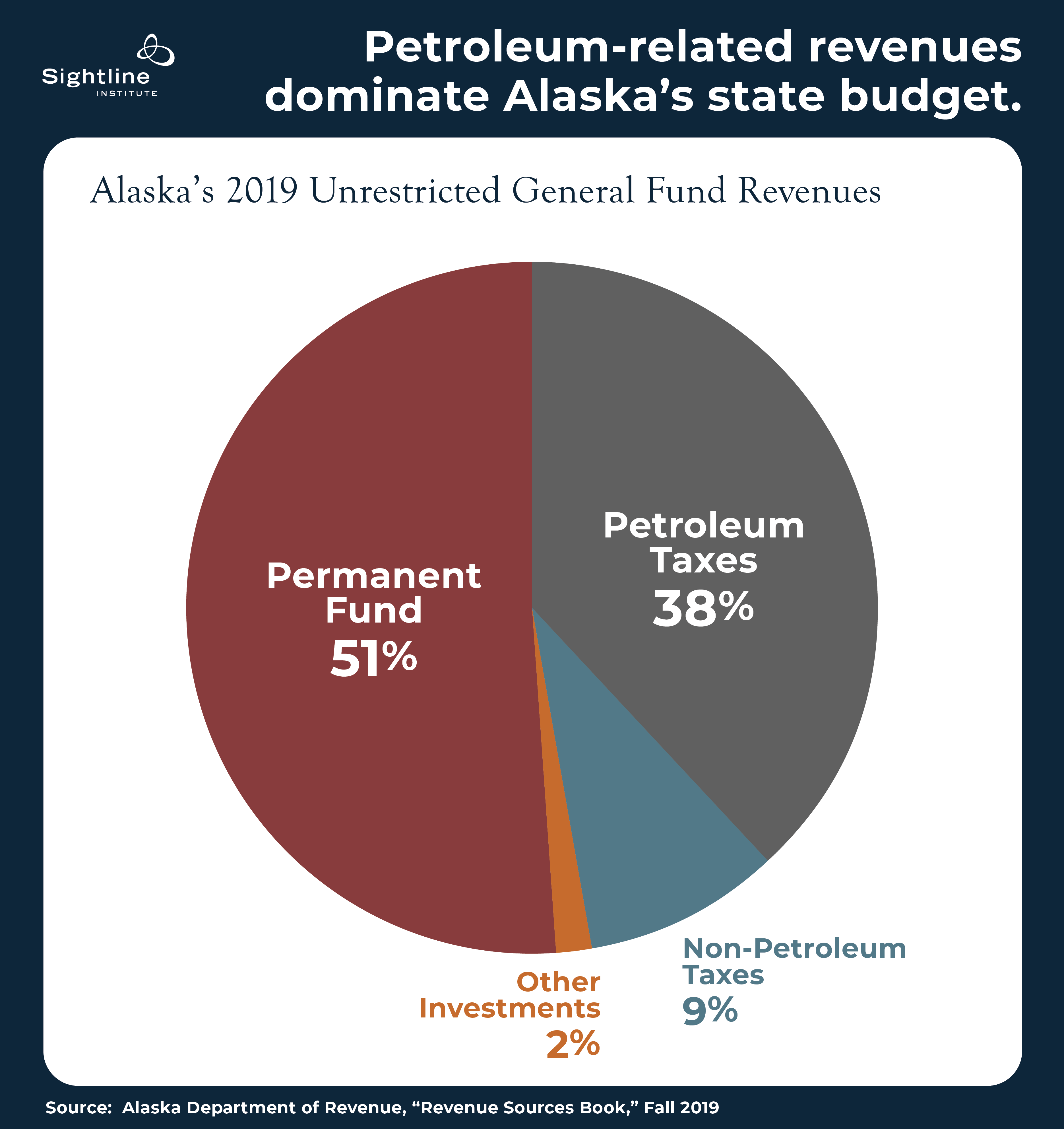

Aside from the money deposited into the Permanent Fund, petroleum is expected to provide between 70 and 74 percent of unrestricted state revenue over the next 10 years. But as oil production decreases, potential revenue decreases as well. Petroleum revenues amounted to $2.6 billion in 2019 and are projected to fall to under $1.8 billion by 2024, although the actual decline may be steeper because these projections assume a relatively stable oil market. Alaska has no state sales tax, no state property tax, and no income tax, so other sources of revenue are scarce. In fact, all the non-petroleum revenues together made up only around a quarter of Alaska’s unrestricted funds in 2019. These revenues were primarily from alcohol taxes ($20 million), tobacco taxes ($40 million), insurance premium taxes ($72 million), fisheries taxes ($28 million), and non-petroleum mining taxes ($45 million).

Alaska finances: Petroleum-related revenues dominate the budget. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

Although the state has no taxes on property or sales, Alaska’s local governments do. Local governments collected about $1.86 billion last year (less than a quarter of what the state took in), with $1.45 billion from property taxes, $260 million from sales tax, and the remaining balance from miscellaneous taxes. Further, the state’s budget consists of two major categories of revenue: restricted and unrestricted. Unrestricted revenue sources (described above) compose around half of the state budget and are available to fund general government spending and capital expenditures; they are not tied to fund any specific programs. The other half of the budget consists of restricted revenue—money placed in reserves or used for specific purposes, based on legal requirements or custom. (Some “restricted” revenue, however, is actually available for general spending; it’s only labeled as restricted because of accounting traditions.) Federal funds for health care, highways, education, and other specific purposes are considered restricted. Other restricted revenue can come from investment earnings or oil revenue and may be used to fund designated programs, such as oil spill responses or seafood marketing.

The final piece of Alaska’s savings accounts is the Constitutional Budget Reserve Fund. Created in 1990, the Budget Reserve Fund consists of money the State receives from the resolution of mineral-related income disputes. The Budget Reserve Fund has dropped from more than $10 billion in 2015 to less than $2 billion in 2019—a victim of legislative raiding in 2019 to plug massive budget holes. More recently, the legislature drew $1.1 billion (70 percent of the remaining amount) to fund the 2020 budget. At this rate, Alaska’s Legislative Finance Division projects the Fund will run out of money in 2022.

The Legislature is also siphoning money from the Earnings Reserve Account to paper over its budget deficits. In March it approved a budget that would draw $3.1 billion from it. In fact, the decline in oil revenue is so pronounced that a greater portion of Alaska’s 2020 revenue came from the Earnings Reserve Account than from taxes from oil and gas production and royalties. Continued reliance on it could draw the account down to zero within 10 years. Without the Earnings Reserve Account to cover Alaska’s structural deficits, the legislature will have to either severely cut spending or find other sources of revenues.

In the time of COVID-19, Alaska’s tenuous 2020 fiscal situation is likely the new normal. Unless prices rebound enough to make drilling on the North Slope profitable again, Alaska’s oil production will continue to decline, further stressing the state budget. Oil companies in Alaska are currently cutting production and slashing their planned capital investments, which means thousands of lost employment opportunities in the state. These are well-paying jobs; the average income for industry employees is $135,000. And although nearly 40 percent of oil industry workers live outside Alaska, the loss of jobs can still be very harmful to Alaska’s economy because of the ripple effect of fewer workers spending money at Alaskan businesses.

Alaska’s use of oil revenues worked for a while, but the path has dead-ended in fiscal disaster. The way forward is likely both simple and very challenging; it involves: shifting away from a dependence on oil and gas for state revenues. This could entail creating new revenue sources like a sales tax or income tax, and it could even mean eliminating the Permanent Fund Dividend.

To better understand what Alaska’s fiscal future might hold, in our next article we will compare Alaska’s Permanent Fund to two other models for managing oil wealth: North Dakota’s newly established Legacy Fund and Norway’s enviable sovereign wealth fund.

Thanks for Paelina DeStephano, who contributed research for this article.

Zane Gustafson is a freelance researcher who holds a master of public affairs degree, with a focus in climate policy, from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. He also studies foreign affairs, political rhetoric, and American history.

Aaron

Alaska needs to export water! So many states are in dire need, and other countries, like Canada, are working on meeting future demands. Alaska could export water like oil, but if they don’t get on it they will lose out to other players that will dominate the market.