When Amazon announced that its new pro hockey arena in Seattle would be called “Climate Pledge Arena,” it was clear that 2020 would be a year of splashy corporate announcements about fighting global warming. Not only will the future home of the Kraken be the first net zero carbon sports arena in the world, but Amazon pledged to be net zero carbon across all of its businesses by 2040. Meanwhile, Microsoft announced it will go a step further: aiming to be carbon negative by erasing all future emissions as well as past emissions going back to the founding of the company in 1975.

These are big aspirations by big companies, but how likely are they to succeed? And, are other leading Northwest corporations following suit? To answer those questions, we examined eleven Northwest Fortune 500 companies to see how these revenue leaders are leading on climate responsibility. We believe the exercise is useful because these 500 companies represent about two-thirds of the United States’ gross domestic product and an outsized number of them call Cascadia home.

As discouraging as the federal government’s failure may be, it is possible to find reasons for cautious optimism in climate action at other scales, including city and state leadership, and increasingly, in corporate America.

Our roster of companies includes nine well-known firms that are headquartered in the US Pacific Northwest, plus two with a significant history and ongoing presence in the region. We included Boeing because 45 percent of its workforce is located in Washington, which was formerly home to its corporate headquarters. And, Intel made our list because 18 percent of its workforce is in Oregon, about 21,000 employees. By comparison, Google has less than five percent of its workforce in the Northwest while Facebook has around ten percent. Our review did not capture some other Northwest companies that rank in the Fortune 500, including Weyerhaeuser (457), Expedia (263), Expeditors International (389), Fortive (422), Lithia Motors (252), and Micron Technology (134). We did include Alaska Airlines and Nordstrom; although they are smaller than some in the former list, we felt they warranted inclusion because they are such prominent public-facing brands.

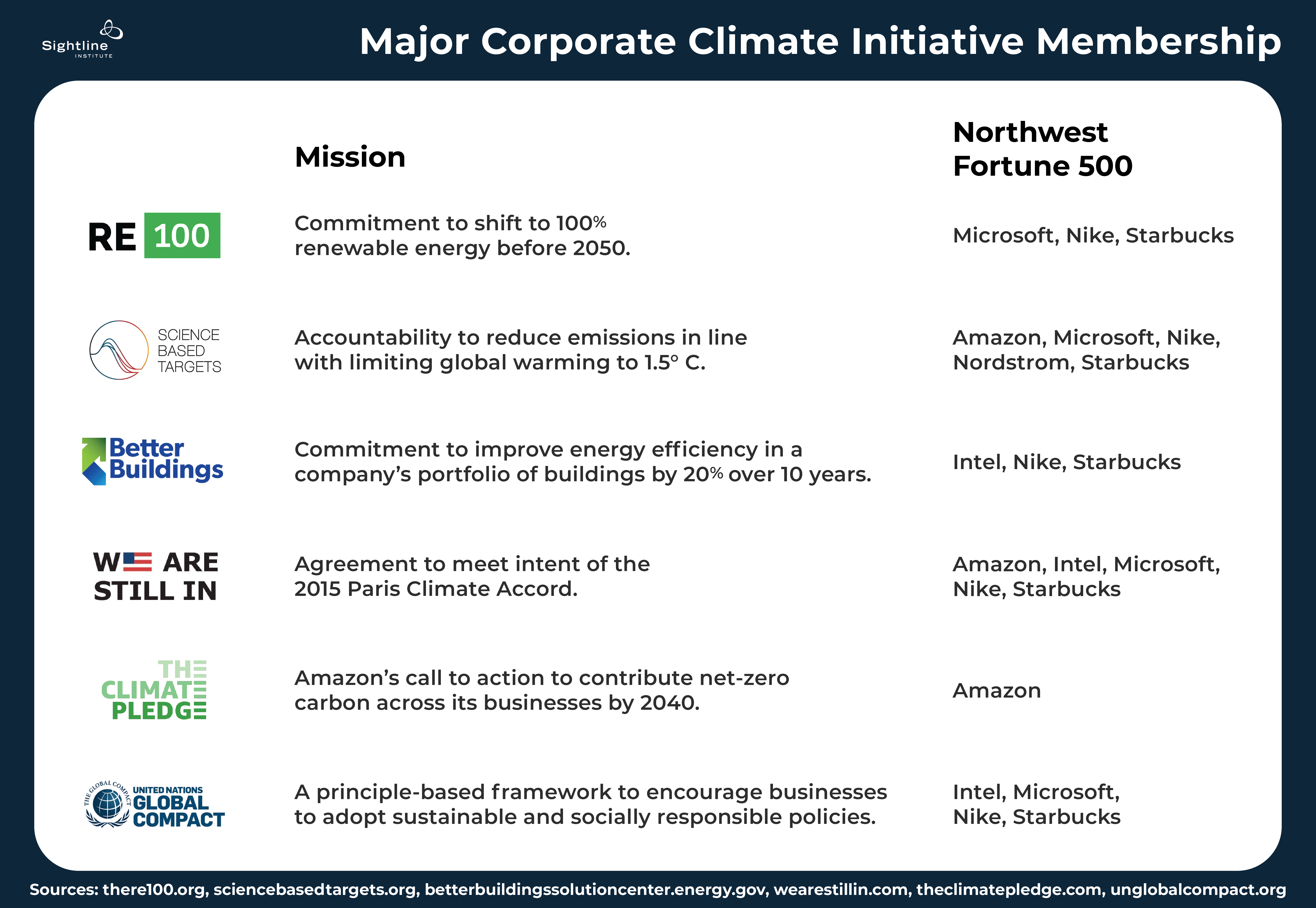

To evaluate the seriousness of the eleven companies’ climate commitments, we focused on three areas: (1) reducing carbon emissions, (2) using renewable energy, and (3) implementing energy efficiency measures. We also surveyed their membership in and partnerships with six major climate change initiatives that provide important frameworks for corporations trying to combat climate change.

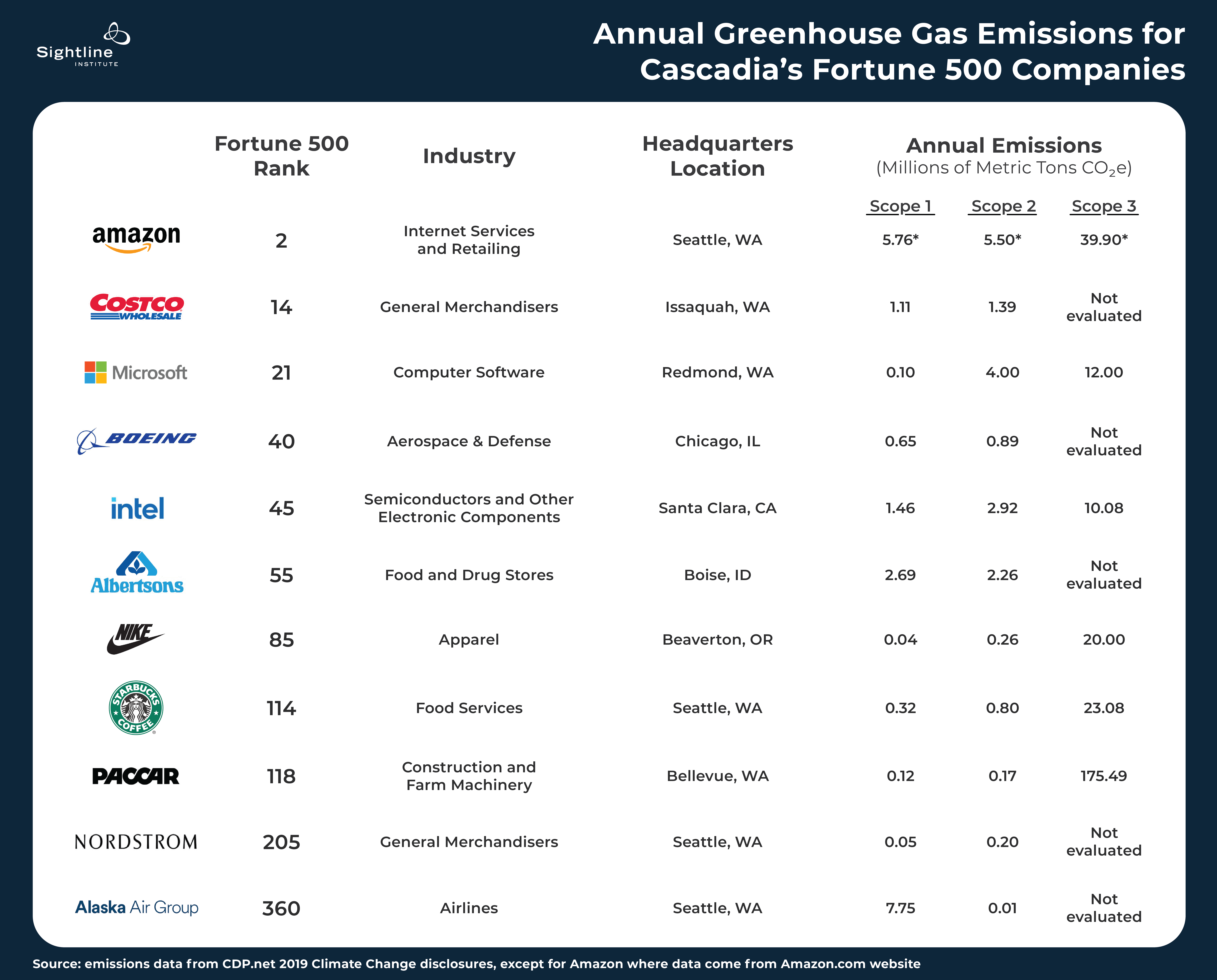

Before we dive into our findings, a quick note about corporate emissions will help make our analysis intelligible. Carbon analysts generally break down corporate emissions into three categories:

Before we dive into our findings, a quick note about corporate emissions will help make our analysis intelligible. Carbon analysts generally break down corporate emissions into three categories:

- Scope 1 includes direct emissions from sources like fuel and refrigerant use in company facilities and vehicles;

- Scope 2 includes indirect emissions from purchased energy, such as gas-fired power from an electric utility;

- Scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions from activities like business travel, employee commuting, the use of products sold, transportation and distribution, and supply chain purchases.

A real-life illustration of these categories may help make clear the distinctions. Microsoft counts the exhaust from its corporate vehicle fleet in Scope 1 emissions. The company’s Scope 2 carbon emissions are those attributable to powering its physical operations like data centers and office buildings, which includes the electricity it buys from utilities. And, when a teenager switches on her Xbox for gaming, whether in Redmond or Rome, the emissions from the electricity powering the device are counted as Microsoft’s Scope 3 emissions. In fact, Scope 3 contains all other emissions rooted in Microsoft’s existence, everything from the gasoline burned by employee commuting, to jet fuel for business travel and global product shipment, to all relevant emissions from their suppliers. Not surprisingly, Scope 3 emissions are typically a company’s largest category of emissions, as well as the most difficult to calculate.

Here’s how they stack up.

Cascadia’s Standouts

Cascadia’s Standouts

Three of the eleven Northwest companies we examined emerge as leaders when it comes to making commitments that really move the needle: Microsoft, Amazon, and Starbucks. All three will be sourcing 100 percent renewable energy for their business (reducing their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions), and all three are promising to slash their total emissions, including Scope 3 emissions. Some highlights:

- Microsoft stands alone in its pledge to be carbon negative by 2030. It has also made a broader promise to, by 2050, erase all of its historical carbon emissions (at least those in Scope 1 and 2) dating back to the founding of the company in 1975. By purchasing renewable energy credits, Microsoft had by 2016 already met the RE100 standards for 100 percent renewable energy. But now the company is pledging to go even further, obtaining 100 percent renewable energy through power purchase agreements for all of its physical operations, including data centers, buildings, and campuses by 2025.

- Amazon co-founded The Climate Pledge in 2019, announcing its plan to become carbon neutral by 2040, a decade ahead of the Paris Climate Agreement timeline. For a company with a huge distribution and transportation reach, zeroing out the emissions footprint of its shipments will be a cornerstone of the strategy. Amazon recently moved up its timeline to source 100 percent renewable energy by 2025 and is currently around 42 percent renewable energy.

- Starbucks will meet its renewable energy goal in 2020, sourcing 100 percent of its energy for its global operations from renewable sources through a combination of solar and wind power purchase agreements as well as renewable energy credits. The firm has a goal to reduce all emissions by 50 percent by 2030, with an aspirational goal to be resource positive, storing more carbon than it emits, by 2050.

In the original version of this article, we awarded an honorable mention to Intel and Nike, but the honor is undeserved. Intel is sourcing 100 percent renewable power for its US and European Union operations (which works out to be 71 percent globally) and has cut their product’s overall carbon footprint substantially. Nike is sourcing 100 percent renewable energy for its business by 2025 and has pledged to reduce carbon by 65 percent for Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and 30 percent for Scope 3 by 2030. Since publication, we have learned that both companies sit on the executive committee of the Oregon Business & Industry association which, along with a coalition of industry groups, recently sued Oregon Governor Kate Brown arguing that she illegally issued an executive order adopting new standards aimed at sharply reducing Oregon’s greenhouse gas emissions over the next 30 years.

The Carbon Footprint of “Made in the Northwest” Products

Two companies on our list are major manufacturers of products that consume fossil fuels: Boeing with its jets and PACCAR with its semitrucks.

Boeing has easily the largest Scope 3 footprint—the carbon emitted by people using its product—of any company on our list. Commercial aviation makes up two percent of the world’s carbon emissions or 915 million metric tons annually, and Boeing’s commercial aircraft likely account for a little less than half of that, if market share is any indicator. Adding to that are the unpublished emissions from the defense and space aircraft that Boeing produces. PACCAR, a major manufacturer of medium-duty and heavy-duty trucks, including Peterbilt and Kenworth big rigs, has attempted to estimate the carbon footprint of its in-service trucks and other Scope 3 emissions at 175 million metric tons; Boeing has not.

Still, both are improving. Boeing and PACCAR have put meaningful engineering effort into improving the fuel efficiency of their products, in each case driven by governmental carbon regulation. In 2011, the US Environmental Protection Agency put in place standards that drove a 10 to 21 percent improvement in fuel economy for heavy duty trucks by 2014 and a requirement for a three percent improvement beyond that by 2017. Model year 2019 PACCAR trucks improved fuel economy and carbon dioxide emissions by 14 percent over 2014 models. And last summer, Europe adopted a CO2 emissions standard for heavy-duty vehicles that will drive a 30 percent cut in their CO2 emissions by 2030.

As part of a global agreement brokered by the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) that established new fuel efficiency standards for aircraft, Boeing has committed to a 1.5 percent average annual improvement in fuel efficiency of its commercial aircraft. The company hopes to achieve this goal by both retrofitting older planes with aerodynamic technologies like winglets and engineering new aircraft with lighter materials and more efficient engines. This commitment is part of a larger suite of goals that support the aviation sector in achieving CO2 reduction for carbon-neutral growth in the airline industry by 2020 and halving the net CO2 emitted by this sector by 2050. Each new airplane Boeing develops is 15 to 20 percent more efficient than the product it replaces, so as we see airlines retiring older, less-efficient aircraft during the COVID-19-induced travel downturn, carbon footprints will improve because the mix of in-service aircraft is, on-average, becoming more fuel efficient.

While vehicle manufacturers have far more energy-intensive products, other Northwest manufacturers have made similar commitments for their products. This year, Intel is developing notebook computers that use just one-fourteenth the energy of its 2010 models. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s and Amazon’s cloud computing services, an alternative to on-premises data centers, are around 85 percent more energy efficient than traditional on-site server infrastructure. Coupled with Microsoft’s and Amazon’s 100 percent renewable energy commitments, these cloud computing services could reduce carbon emissions by between 88 and 95 percent over on-premise data centers.

Misguided Efforts

PACCAR deserves credit for tabulating (and sharing) the carbon emissions that come from using its trucks, but it should get dinged for a misguided strategy: using natural gas to try to achieve emissions reductions. PACCAR counts among its “low carbon” offerings compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquid natural gas (LNG) engines as alternatives to trucks powered by diesel or gasoline. The company supplies more than 50 percent of the market for fracked gas trucks, but the industry has so far failed to acknowledge that the all-in greenhouse gas emissions related to fracking, moving, and compressing or liquefying natural gas erase all of the alleged climate improvements.

PACCAR is not the only company to make this misstep. Natural gas features prominently in corporate strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by both Albertsons and Nordstrom. Both firms identify fracked gas trucks for their distribution operations as part of their strategy to reduce their carbon footprint.

Other Highlights, Plus Some Lowlights

Alaska Airlines, a major North American airline carrier, has the best carbon footprint ranking for any US-based carrier according to a 2018 atmosfair report. Globally, however, the picture is less rosy: Alaska is ranked just 22nd worldwide out of 125 airlines, after slipping from 14th place in the 2017 report. The airline’s 2019 sustainability report indicated that the company had achieve a 16 percent reduction in emissions per revenue-ton-mile over 2012 due to the use of efficiency-enhancing winglets and navigation technologies. Still, officials acknowledge that this achievement is unlikely to fulfill the company’s goal of reducing emissions 17 percent below 2009 levels.

More worrisome, by early 2020, Alaska Air’s overall Scope 1 and 2 emissions were up by a whopping 70 percent in the past 5 years. (The collapse in air travel following the Covid-19 pandemic has almost certainly reduced these figures substantially.) Like Boeing, Alaska Air has voluntarily agreed to meet the UN’s CORSIA goals designed to cap aviation emissions at 2020 levels, though the program has received sustained critique from some climate hawks.

The company currently has no operations powered by renewable electricity, although in 2019 it did commit to fueling its now-grounded 737 MAX aircraft with a blend of biofuel and traditional jet fuel. Alaska Air is working with airports in Seattle and San Francisco to develop a strategy for sourcing sustainable aviation fuel. These biofuels may be able to reduce carbon emissions, but the availability of the feedstock to produce them sustainably is currently limited and scaling up may have broader negative consequences for the environment.

Albertsons, a major US grocer that owns Safeway and Haggen, has not made transformational climate commitments nor joined any of the major initiatives that we surveyed combatting climate change. Like Costco, the company has on-site solar generation prominently featured in its corporate sustainability report, although it amounts to less than one-half of one percent of its annual energy use. Alberton’s has no published emissions reduction or renewable energy targets. While proactive on deploying money-saving energy efficiency upgrades in its stores, the company seems to be primarily following consumer interest in climate-friendly behavior, which has thus far been insufficient to spark meaningful change beyond trying to burnish its reputation.

Amazon is launching a $2 billion climate fund to pursue investments in clean energy and technologies to combat climate change. And, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is donating another $10 billion of his personal fortune to fight climate change. In addition to other admirable pursuits like powering Amazon with 100 percent clean energy by 2025 and becoming net zero by 2040, Amazon announced it is ordering 100,000 electric delivery vehicles (so that 50 percent of all shipments will use net zero carbon in their fulfillment, packaging, and transportation by 2030). The company has also named the Seattle’s new professional hockey venue, “Climate Pledge Arena.” Unlike its peers who have signed onto third-party led climate initiatives, Amazon is home-growing its own climate initiative, filling a space where other accepted programs already exist. Still, the company has had four other corporations join its pledge: Infosys, Mercedes Benz, Reckitt Benckiser, and Verizon.

Yet for all these positive actions, Amazon works against the climate as well. The company has very diverse business arms—cloud computing, online retailing, and grocery delivery just to name a few—including some highly carbon intensive components. Most prominent is its global logistics network that depends heavily on fossil fuels for air and ground transportation, along with energy-intense server farms across the world. Amazon generates around 50 million metric tons of carbon annually, comparable to the carbon footprint of entire countries like Switzerland or Norway. Worse, its artificial intelligence technology is used by oil and gas companies to improve drilling prospects, improving their profitability. Donations from Amazon have gone to climate science denying organizations. And, Amazon has threatened to fire employees who have been vocal about Amazon’s contribution to climate change. On that score, Amazon’s employees deserve a round of applause for pushing the company toward faster climate action.

Boeing sells airplanes around the globe, so its business success is linked to international protocols governing climate. The most prominent of these in the aviation sector is the UN’s market-based measurement system called Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) that has so far been adopted by 78 countries. In order to remain competitive, Boeing now engineers aircraft that meet the CORSIA fuel efficiency standards, which aim to halt carbon emission growth in aviation starting in 2020 and halve carbon emissions by 2050.

CORSIA’s 2050 goal would be achieved, in a large part, by using alternative jet fuels with a smaller carbon footprint, especially biofuels. Boeing has already experimented with these biofuels, flying around 1,600 miles in partnership with Alaska Air, and has shown that they are technologically viable. Commercializing these biofuels will prove to be a bigger challenge because of the difficulty of harvesting, processing, and distributing biofuels, not to mention making them cost-competitive with fossil fuels.

Internal to the company’s operations, Boeing set 5 environmental goals in 2018. By 2025 the company aims to: reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent, reduce water consumption by 20 percent, reduce waste to landfill by 20 percent, reduce energy consumption by 10 percent, and reduce hazardous waste by five percent. Many of these are a tall order. According to its most recent scorecard, Boeing actually increased water consumption and hazardous waste production. It may also need to accelerate progress on greenhouse gas emissions and energy goals, both of which improved in 2018 but neither of which appear to be on track. Boeing’s internal goals may appear less aggressive compared to peers in our evaluation who have found pathways to become carbon neutral, have zero-waste facilities, or have reduced energy use in their facilities by 20 percent or more.

Costco, a multinational warehouse store, has not made transformational climate commitments nor joined any of the major initiatives combatting climate change that we surveyed. The main efforts cited in its sustainability report address reducing energy intensity in its operations through efficiency projects, like switching to LED lighting and implementing energy management systems. Its corporate website mentions a focus on land stewardship, forestry, packaging, transportation, human rights, agriculture, and fisheries, although there are few specifics. Costco boasts about some renewable energy projects on its website, but these supply less than two percent of its annual energy consumption. Costco’s biggest identified risk related to climate change in its 2019 CDP disclosure is whether extreme weather will prevent customers from shopping.

Intel, a leading semiconductor manufacturer, identified goals for clean energy, emissions, and energy efficiency. It is sourcing 100 percent renewable energy for its US and EU operations, which works out to 71 percent of its global energy demand. Intel was aiming to improve its notebook and server products’ energy efficiency by 25 times beyond 2010 levels by 2020 but it fell short, achieving instead a 14-times improvement for notebooks and an 8.5-times improvement for servers.

From 2018 to 2019, Intel reduced the intensity of its Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions by 13 percent—that is, it reduced emissions per unit of production—but its absolute emissions still increased by eight percent because the company was producing more than ever. Intel’s story is actually a common one: companies are becoming more energy- (and carbon-) efficient but manufacturing more, which expands its overall carbon footprint. Perhaps it is for this reason that Intel is fighting Oregon’s new rules that would drive down emissions by participating in a lawsuit targeting Oregon Governor Brown’s executive order that caps greenhouse gas emissions.

Microsoft leads the Northwest in meaningful climate commitments as well as goals accomplished: the company is already carbon neutral and uses 100 percent renewable energy in its business, accomplished in part by buying carbon-free electricity on the open market instead of the carbon-rich electricity offered by Puget Sound Energy. In January 2020, Microsoft pledged go carbon negative—removing more carbon from the atmosphere than it puts in by 2030. And, to take it a step further, by 2050, Microsoft aims to erase its historical carbon footprint since the company’s founding in 1975. Like Amazon, Microsoft is backing its pledge with a major investment: $1 billion toward decarbonization strategies that will help it and other emitters remove carbon from the atmosphere.

However, Microsoft does earn a demerit. Like Amazon, the software giant continues to form and maintain business partnerships with the oil and gas sector. In fact, Microsoft announced new deals in 2019 with Chevron and Schlumberger for cloud computer services. The company says it can work with the fossil fuel sector to help it “evolve.”

Nike claims to be motivated by the future of sports (because temperature changes may affect the duration of playing seasons, clothing options, and safety), and so the company has identified several initiatives to combat climate change. In fact, Nike has joined most of the major climate change initiatives we surveyed and has an active focus on climate But even with Nike’s highly publicized positions on sustainability, Nike is working against climate progress. The company sits on the executive committee of the industry group currently suing to stop the Oregon Governor Brown’s executive order mandating steep emissions reductions in Oregon. Despite its earlier support for Oregon’s failed cap and trade legislation, Nike’s role in this lawsuit cannot be ignored.

The company is making some baby steps in the right direction, however. Like the leaders on our list, Nike committed to sourcing 100 percent renewable energy for the facilities it owns and operates facilities by 2025. Yet facility management is not really Nike’s core carbon problem. More than 90 percent of the firm’s carbon footprint is attributable to its global supply chain, which Nike does not own and operate, and which is not included in its renewable energy pledge. In 2016, Nike signed onto the Paris Climate Agreement, and in doing so, has committed to reducing carbon emissions in its global supply chain by 30 percent by 2030, with a vision (but not a commitment) to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Nike is also participating in the Better Buildings Challenge with a goal to reduce energy use by 20 percent from 2015 levels by 2025 on its 10.8 million square feet of US-based buildings. But with so much of its carbon emissions in its supply chain, the company’s pledges feel lackluster until they extend beyond the Nike-owned footprint.

Nordstrom, a luxury department store chain in North America, announced in April 2020 (the 50th anniversary of Earth Day) that the company would be setting a science-based target for reducing Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Details about this target are still forthcoming, but Nordstrom is already offsetting 100 percent of its emissions from its 13 Western Washington stores using Forterra’s Evergreen Carbon Capture Program. In 2018, Nordstrom stores had improved energy efficiency by 17.1 percent over a 2014 baseline. By the conclusion of this year, Nordstrom aims to buy 30 percent of its total energy from renewable sources. In 2019, Nordstrom also joined the G7 Fashion Pact in which signatories committed to greenhouse gas emission reductions, renewable energy, single-use plastic elimination, and other eco-goals.

PACCAR, a semitruck manufacturer, has made no formal climate commitments nor joined any of the major initiatives combatting climate change that we surveyed. Nonetheless, the truck manufacturer has notched a few meaningful environmental achievements and it is pursuing product designs that indicate it is taking some responsibility for climate change.

The challenge goes right to the heart of its business because PACCAR’s products run on fossil fuels. Demand for electric trucks is growing, however, and PACCAR is prototyping several zero-emission trucks to meet emerging requirements across the globe (although none are yet commercially available). It also joined the US Department of Energy’s Supertruck II initiative to improve the efficiency of 18-wheelers, the trucks that haul 80 percent of goods in the US, and in doing so, use about 28 billion gallons of fuel per year. But it could go much further. By comparison, PACCAR’s major competitor, Daimler (maker of Freightliner, Western Star and Mercedes-Benz trucks), has pledged to make its entire commercial fleet carbon neutral by 2039.

Internal to the company’s operations, PACCAR spent $160 million in the past 10 years on energy efficiency, as well as reducing emissions, water use, and waste. PACCAR has also sliced its greenhouse gas emissions by 29 percent on a per revenue basis between 2009 and 2018, although its actual emissions have increased overall as its revenue has grown. One positive sign is that eighty-eight percent of its manufacturing locations achieve zero waste to landfills.

Starbucks announced in January 2020 that it was “striving” to become resource positive—that is, storing more carbon than it emits, eliminating garbage, and providing more water than it withdraws. The coffee giant has also made some hard commitments, include cutting carbon emissions by half for its direct operations and supply chain, replacing half of the water used for coffee production and operations, and eliminating half of its landfill-bound waste, all by 2030. For its 50th anniversary in 2021, Starbucks plans to formalize its goals and plan.

In 2018, Starbucks announced its plan to operate 10,000 LEED-certified stores, in conjunction with its pledge to reduce by 25 percent the energy intensity of 12 million square feet of stores in 70 countries by 2025. The company made progress. By the end of 2019, all US, Canadian and UK stores ran on renewable energy and 72 percent of its global operations were powered by renewable energy. In fact, Starbucks will be powering all global operations with renewable energy by the end of 2020.

Yet for all its leadership on climate change, Starbucks has also been a leader in creating the to-go, disposable culture that pervades today. Previous efforts to meet a 2015 goal to reduce waste by encouraging a quarter of customers to use reusable cups fell drastically short, proving that getting consumers on board is a major hurdle to the success of goals like these. To achieve significant emissions reductions, consumers would also need to start opting for plant-based milks to lighten their java; dairy makes up 21 percent of Starbucks’ carbon footprint.

Corporate Outlook

There can be little doubt that the US federal government has failed to address climate change in a meaningful way. Although the national policy response has been especially horrendous under the Trump Administration, it was never adequate under President Obama and there is good reason for skepticism about the prospects for climate progress in a Biden administration. Still, as discouraging as the federal government’s failure may be, it is possible to find reasons for cautious optimism in climate action at other scales, including city and state leadership, and increasingly, in corporate America.

It is heartening then that some of these giants, like Microsoft and Amazon, have emerged as leaders willing to bankroll—and stake their reputation on—reversing the environmental damage where they have been contributors. Many others, like Costco and Albertsons, clearly have much more to do, but they may yet be responsive to customers who demand more meaningful action than the PR campaigns that may have worked in the past. As the region’s politics and culture gravitate toward more aggressive action on climate change, those companies based in Cascadia may be poised for big change.

Cascadia’s Standouts

Cascadia’s Standouts

AndyG

I think you missed a major issue. Many of these corporations are green-washing with their pledges. Every major company based in Oregon is suing the Governor over her attempts to implement some climate change rules. https://www.opb.org/article/2020/07/31/business-groups-sue-oregon-governor-kate-brown-carbon-reduction-policy/

Eric de Place

Andy, is that lawsuit backed by either Intel or Nike?

AndyG

Yes, Intel and Nike are on the Executive Board of one of the plaintiffs, Oregon Business & Industry (https://www.oregonbusinessindustry.com/redesign/obi-board-of-directors/). I don’t think they get to pretend they have nothing to do with it.

Eric de Place

Thanks for bringing this to our attention, AndyG. We are a bit chagrined that we were not aware of their involvement in the lawsuit, and we will be amending our article to reflect that information.

John Abbotts

Readers may not be still following this comment chain, but in an effort to give, “discredit when it is due,” Amazon also treats its warehouse workers atrociously. DemocracyNow! has just posted this news report on the contrast between the increase in Jeff Bezos’s net worth during a pandemic, while the company fights the attempts of its warehouse workers in AL to unionize, link at https://www.democracynow.org/2021/3/23/amazon_workers_union_drive_bessemer_alabama

That is not to mention that some progressive officials have recommend a “pandemic excess profits tax,” on companies that profited during the ongoing plague. And Amazon/Bezos have been cited as poster-boys for this tax, especially since they allow their downtrodden warehouse workers to die of COVID during the pandemic.

These comments are mine alone, but just saying,

All stay safe,

John Abbotts

Again, responsibility for these comments lies with myself alone. But in a “right-wing corporate appeaser bites-corporations,” story, good old Tucker Carlson attacked Jeff Bezos and Amazon, along with other corporations, link at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4o65yNaRIE

Tucker’s comments probably are because Bezos also owns the Washington Post, which consistently criticized the Trump administration, and dare I say it, GOP Treason.

Tucker’s claims might have some teeth if he was not working for multi-billionaire Rupert Murdoch. Is Tucker required to follow Rupert’s daily meme to Fox employees? I do not know the answer, but to ape Tucker’s style, “just asking the question.”

Regards, and All stay safe,