Sightline has provided detailed election reports for every state with recommendations to prepare for a surge in mail-in ballots this November. While some states made significant strides to upgrade their voting systems to make absentee voting more accessible for the general election, others have resisted changes. Vote-by-mail systems are especially important in battleground states, where a small number of votes could swing an entire group of electoral votes to one candidate—and even tip the balance for the entire election. We’ve looked at 18 battleground states and catalogued the biggest hurdles absentee voters face in each.

When it comes to how easy it is for voters to return their absentee ballot, there are three big obstacles: whether voters must get a witness to sign their ballot, whether they have access to a secure drop box, and whether community groups may return signed and sealed ballots for voters.

This is assuming voters can get a mail-in ballot in the first place; voters in Kentucky or North Carolina need an official excuse to vote absentee. In Texas, even lack of immunity to the coronavirus doesn’t cut it.

North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Minnesota require witnesses

Only a handful of states, including three swing states, still have a witness requirement for absentee ballots this year. Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Wisconsin require absentee voters to find a witness to watch them sign their ballot and add their own signature and address. The requirement supposedly verifies the voter’s identity, but courts have struck the requirement down in several states as an unnecessary burden on voters during the pandemic. Thousands of early voters have struggled to get their ballots counted in states that still retain a witness requirement.

In North Carolina, Sightline’s analysis of early general election voting data shows the requirement disproportionately impacts Black voters, who are much more likely to get their ballots rejected due to a witness issue. North Carolina voting rights groups have challenged that state’s witness requirement in attempts to eliminate that voting hurdle for the general election during COVID-19, but state judges this month ruled against efforts to drop the witness rule. In Virginia, a state judge approved removing the witness requirement for the primary; after that, state officials in August agreed to extend the suspension for November.

In battleground states, every barrier that prevents some voters from getting their ballot in and counted could make a difference in the outcome of the election.

Some election officials in Wisconsin, which we gave a C grade for vote-by-mail accessibility, tried to eliminate barriers to absentee voting in the state. But many of those efforts met staunch opposition in the courts—including the effort to remove the state’s witness requirement. While a federal judge temporarily suspended that requirement earlier this year, an appeal reinstated the rule. What’s worse, voters can’t course-correct if they make a mistake and forget to include witness information on their ballots. The state doesn’t allow voters to show up in person at a polling location to vote if they’ve already submitted a ballot with a mistake on it.

Minnesota also has a witness requirement that was waived for the primary and general elections this year. But if the state wants to continue to keep voting by mail accessible next year, it will need to permanently eliminate the rule.

Access to secure drop boxes are limited in Texas and Ohio

Drop boxes can provide an added lifeline for voters who can’t easily mail their ballots or are worried their ballots won’t get to election offices on time via the US Postal Service. Widespread drop-off sites are important election infrastructure for ensuring anyone can vote, regardless of the neighborhood they live in or the reliability of US mail service.

Texas received an F grade from Sightline for its vote-by-mail preparedness, and state officials have continued to fight reforms that would make it easier for voters to cast their ballots by mail or drop box during the pandemic. Governor Greg Abbott, one month before this November’s election, announced he would limit drop boxes to one per county and force local officials to shutter drop-off sites provided in more populated urban areas, such as Austin and Houston. Vote by mail “veteran” Oregon Governor Kate Brown tweeted, “4.7 million people live in Harris County, Texas—to put that in perspective, that’s more than in all of Oregon. ONE ballot drop box for that entire county is unacceptable.” Texas counties with populations of just a few thousand—or even a few hundred—will have the same number of drop boxes as their more populated neighbors.

In Ohio, Secretary of State Frank LaRose also limited drop boxes to election offices, where voters were already able to drop off their ballots.

Expanded access to drop boxes are especially important in states with large Native American populations, such as Montana and New Mexico. Voters living on tribal lands may live far from polling locations or post offices. New Mexico (Sightline absentee voting grade B) has the largest Native American population among battleground states; about one in 10 of the state’s residents identify as Native American, according to the US Census. In Montana (grade B-), six percent of the state’s population is Native.

There are ways to dismantle longstanding hurdles for Native American voters: Minnesota, for example, allows tribal nations to designate a building on tribal land to drop off ballots. Washington Governor Jay Inslee signed a new law that makes voting more accessible on tribal land, including allowing each tribal nation in the state to request at least one drop box for ballots on their land.

Sightline’s recommendation to improve access to drop boxes is crucial in every state. But it becomes even more important in states with large areas of tribal lands—especially when taking into account the disproportionate impact the coronavirus has had on Native American communities.

Nevada and Georgia don’t let anyone return someone else’s mail-in ballot

In at least 29 states, voters who aren’t able to get to the polls or a drop box or post office box in time may hand their signed and sealed ballot to a friend or community member to turn it in for them. This is a particularly important option for people with disabilities, and those living in remote areas.

Nevada (grade A-) is a state that was already well equipped to handle widespread vote by mail, and took it even further this November by mailing all voters absentee ballots. But one of its weaknesses is a state law that bars anyone other than the voter from returning that voter’s ballot. Voters can only designate an immediate family member to return their ballots. Those without family are out of luck.

Georgia stood out among non-Western states in its vote-by-mail access; like Arizona, the state received a B from Sightline. But it also has limitations, allowing only physically disabled voters to designate someone to return their mail-in ballots.

Obstacles in battleground states make a difference for all US voters

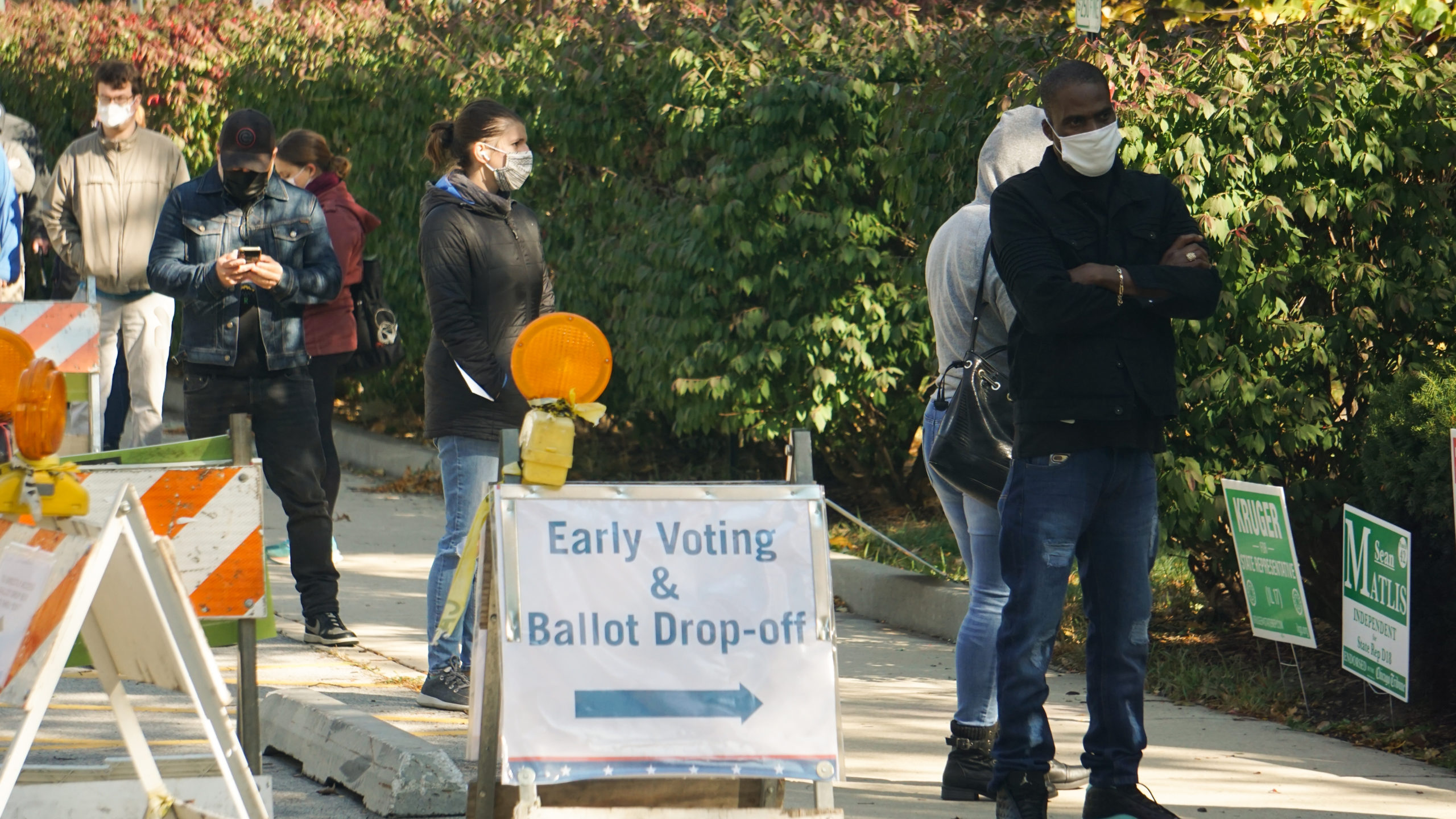

Early voting is underway, and voters across the country have begun receiving their mail-in ballots. States are already seeing an unprecedented number of citizens voting early and absentee. But barriers to returning absentee ballots still remain. In battleground states, every barrier that prevents some voters from getting their ballot in and counted could make a difference in the outcome of the election.

Obstacles to Absentee Voting in 18 US Battleground States

| State | Witness Requirement | Drop Boxes | Limits on Who Can Return Ballot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | None | Allowed | Voter only |

| Florida | None | Allowed | Anyone |

| Georgia | None | Allowed | Voter only; immediate family member for physically disabled voters |

| Kentucky | None | Allowed | In-person return prohibited |

| Maine | None | Allowed | Anyone |

| Michigan | None | Allowed | Immediate family or other household member |

| Minnesota | None | Allowed, must verify identity | Election Day, 3:00 pm if by hand |

| Montana | None | Allowed | Anyone |

| Nebraska | None | Allowed | Anyone |

| Nevada | None | Allowed | Immediate family member |

| New Hampshire | None | Allowed | Immediate family member |

| New Mexico | None | Allowed | Voter’s caregiver or immediate family member |

| North Carolina | 2 witnesses; reduced to 1 witness for 2020 general election | Allowed, must verify identity | Near relatives and legal guardians |

| Ohio | None | 1 per county limit | Close relative |

| Pennsylvania | None | Allowed | Voter only |

| Texas | None | 1 per county limit | Voter only |

| Virginia | 1 witness; none for 2020 primary and general elections | Allowed | Voter only |

| Wisconsin | 1 witness | Allowed | Anyone |

Sightline Institute is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization and does not support, endorse, or oppose any candidate or political party.

Hayat Norimine, research contributor, is a freelance writer who grew up in Washington on the border of Idaho. She previously covered city halls and politics for The Dallas Morning News, Seattle Met magazine, and The Daily News in Longview, Washington. She has an MA in journalism from the Medill School of Journalism and a BA in English from the University of Washington. For Sightline, she researches and writes about democracy reform and elections issues and reports on fossil fuel proposals along the Thin Green Line.

Zane Gustafson, research contributor, holds a master of public affairs degree, with a focus in climate policy, from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. He also studies foreign affairs, political rhetoric, and American history.

For press inquiries and interview requests, please contact Anna Fahey.

Steve Erickson

It would be interesting to compare these voting procedures and obstructions with those in other banana republics. For instance, how does Texas compare with that bastion of freedom and liberty Belarus?