On election night, we knew who won the most votes for president—by a “landslide” scale margin. Yet we didn’t know who’d become president. Despite a decisive national popular vote win, we nonetheless endured a drawn-out and uncertain week until we found out who won the Electoral College. In almost every other context, the candidate with the most votes wins. Why not the president?

Because the Electoral College is built into the Constitution, right? But wait! The Constitution indeed inserts the Electoral College between the people and the president, but it does not say every state needs to use a winner-take-all system where Electoral votes are either all blue or all red, no matter the diversity of its voters. That just happens to be how most states decided to do it. In fact, the US Constitution gives states the power to use the Electoral College to elect the president with the most votes, and 16 states have already signed on (Colorado voters just reaffirmed their desire to elect that president based on votes).

Why doesn’t every state jump on board, and make this the last election where the will of the people could be thwarted by the lopsided distribution of Electoral College votes? The most common argument against letting voters pick the president—a national popular vote—is that only voters in big cities will count. Mike Huckabee, former governor of Arkansas and a 2016 Republican candidate for president, recently argued that, if every vote counted equally, a candidate could win just in a handful of heavily-populated cities.

Sorry Mike, you need to get better at counting votes. Cities wouldn’t have outsized power with a national popular vote.

There just aren’t that many people in cities.

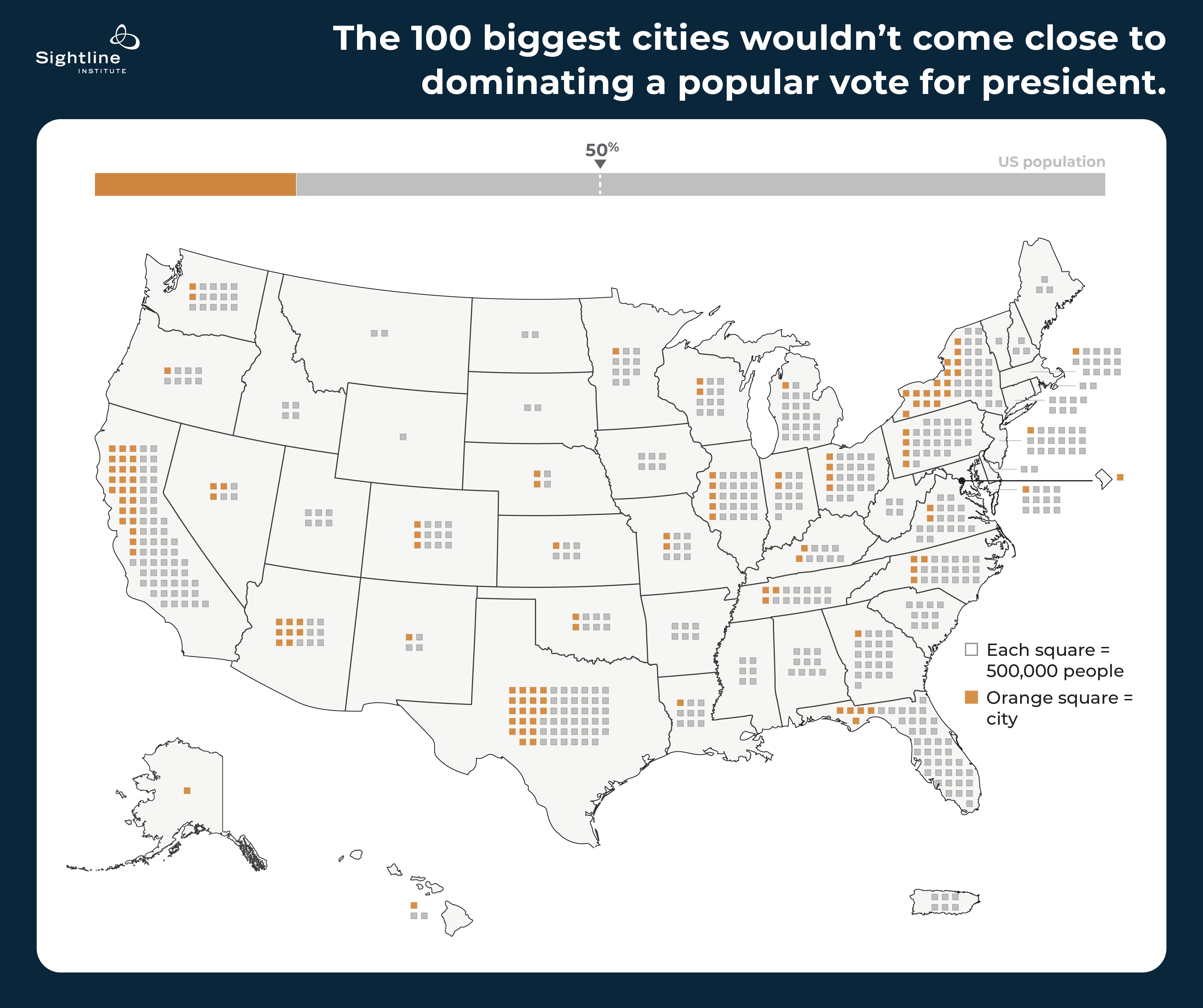

The 100 biggest US cities in the US hold just 20 percent of the population. That list of “big” cities includes Baton Rouge, Louisiana, with 220,000 people. A candidate who tried to win the most votes for president by campaigning only in “heavily-populated” cities would lose.

The map below shows where people live—each square represents 500,000 people. Each orange square indicates 500,000 city-dwellers in that state. There just aren’t enough orange squares to swing an election.

A national popular vote wouldn’t favor cities. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

Even if we included every single city in the country, plus every state capitol (all the way down to Montpelier, Vermont, population 7,600) and every college town, that still only gets our hypothetical “Cities FTW!” campaign to 30 percent of the votes. Still a losing strategy.

There just aren’t that many people in cities. The 100 biggest US cities in the US hold just 20 percent of the population. If every vote counted, no candidate could win with just the urban votes.

Let’s look at it another way. About 27 percent of Americans say they live in an urban area. Most Americans—52 percent—say they live in a suburban area. About 21 percent live in a rural area. If every vote counted, no candidate could win with just the urban votes. Let’s say a candidate appealing to urbanites inspired them to turn out at much higher rates than other parts of the country. With only 27 percent of the people, even if urban areas had double the turnout of every other part of the country and voted heavily for one candidate, that still wouldn’t be enough. To win the popular vote, a candidate would still need to compete for voters outside the cities. If one candidate appealed to urban voters and the other to rural, the path to victory would be through the suburbs, not through the cities.

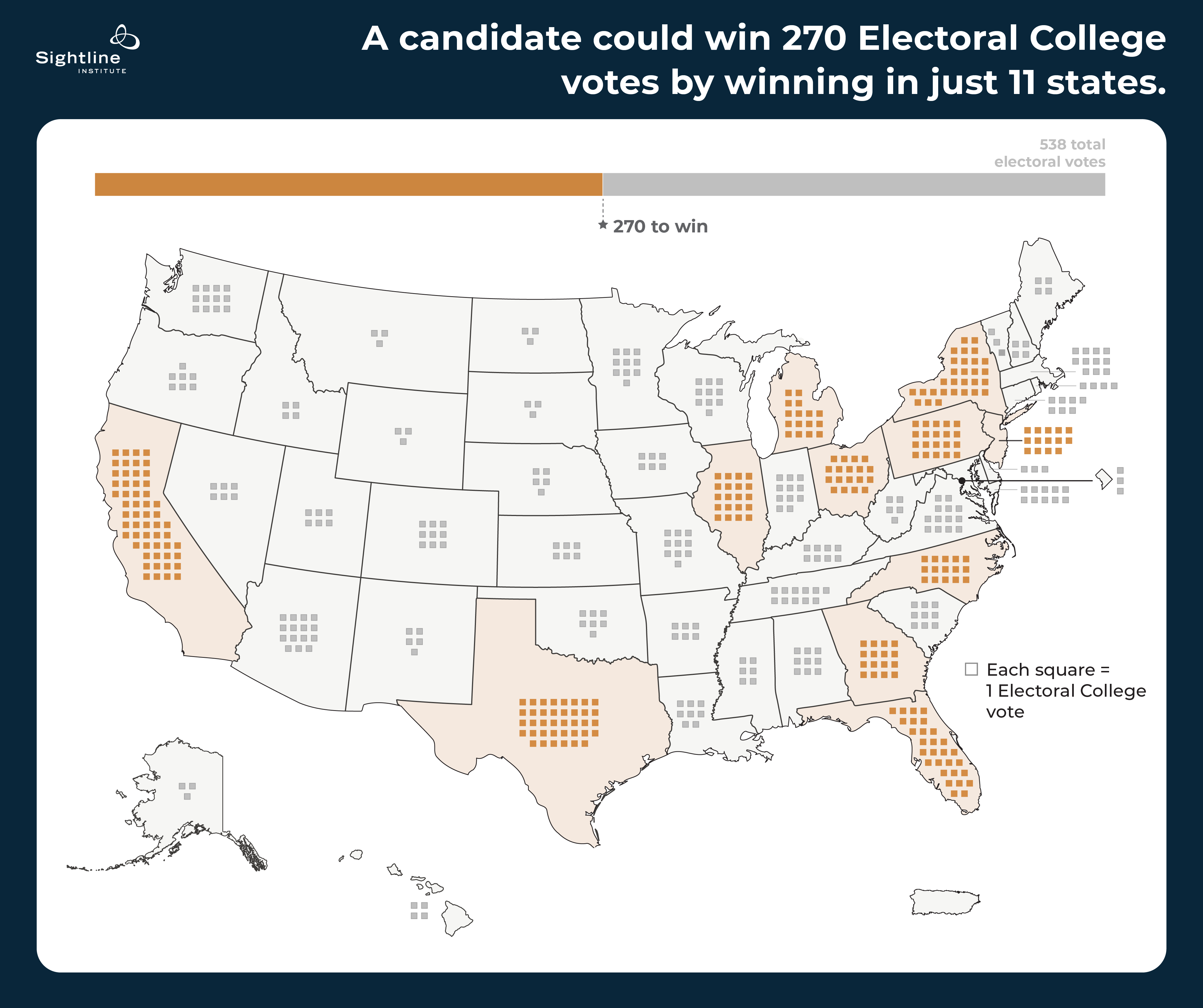

A candidate could win the Electoral College with just 11 big states.

Though defenders of the status quo often bring up the big city boogey-man, let’s broaden the argument and say they are afraid that counting every vote equally could mean a candidate could win by racking up big vote counts in certain heavily-populated cities, states, or regions. Note that with the winner-take-all set up for the Electoral College as it is, that is true right now! We’ve just seen how the presidential election hung on a handful of battleground states.

It’s true that with the state winner-take-all Electoral College, a candidate would only need to win the most votes in the 11 biggest states to win the presidency. Together, California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, Michigan, and New Jersey have 270 Electoral votes. In the map below, each square represents one Electoral vote, and there is a path to Electoral College victory through just 11 large states, losing every other state in the Union.

A national popular vote wouldn’t favor cities. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

Ironically, this is the exact horror that some use to argue for the current state-winner-take-all set-up. Like this Fox New contributor: “Would presidents be selected primarily by voters in our most populous states—with California, Texas, Florida, and New York topping the list—really reflect the diverse beliefs and interests of our vast country? Of course not.”

If the winner-take-all Electoral College’s big saving grace is that it diverts candidates’ attention away from big states and towards smaller ones, it is failing.

And yet, states’ decisions to allocate all their votes to one candidate means big battleground states hold all the power. The path to winning the Electoral College in the current state-winner-take-all setup runs directly through the largest states. Look at that map again and you’ll see those big, populous states, rife with big cities, are where presidential battles are waged. In 2016, Trump won seven of those big states, carrying him to the presidency. In 2020 Biden won seven of them for the win.

If the winner-take-all Electoral College’s big saving grace is that it diverts candidates’ attention away from big states and towards smaller ones, it is failing.

The status quo doesn’t ensure broad support

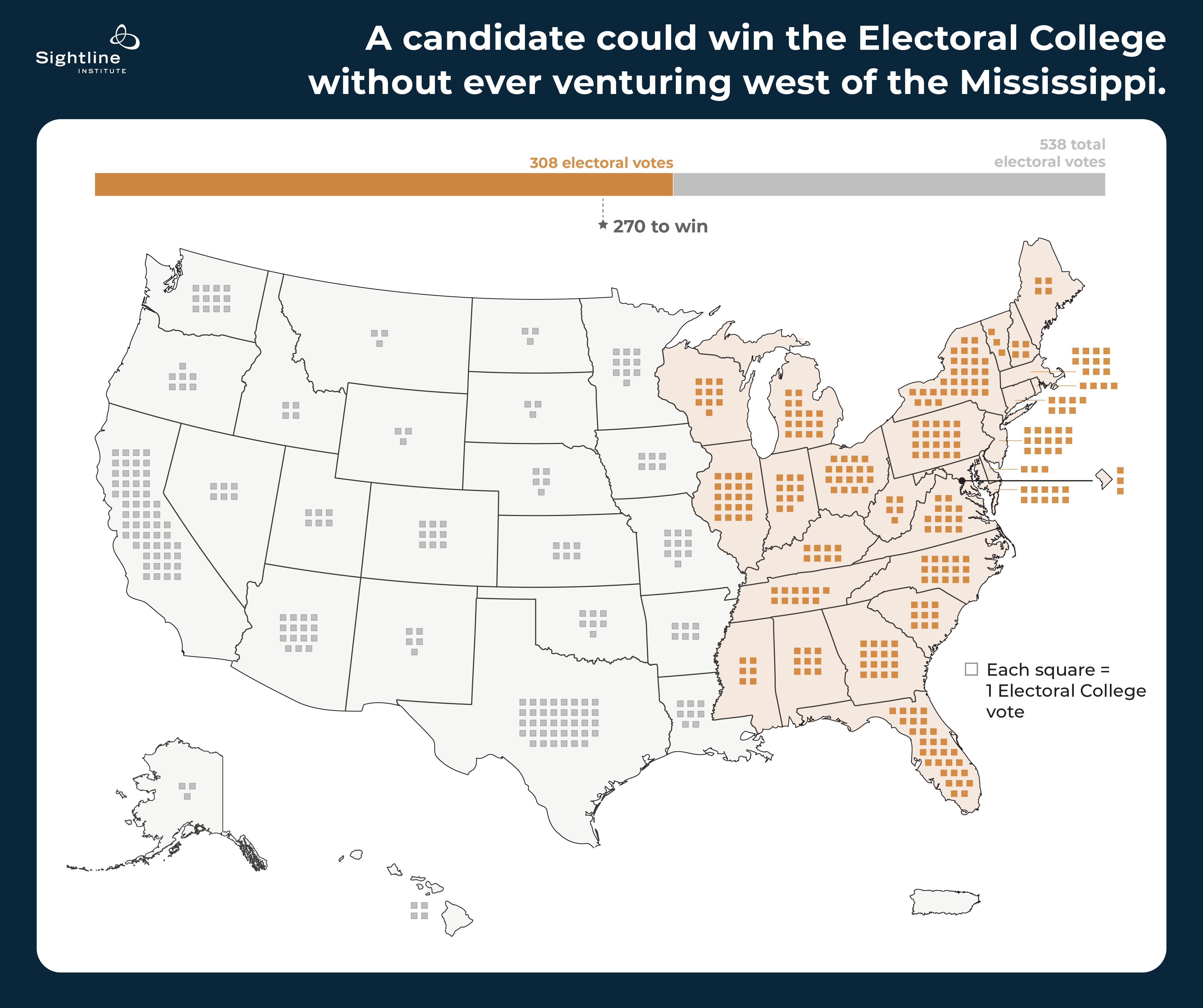

Let’s zoom out even further and assume that the hand-wringing about cities is an extreme expression of the legitimate desire for the president to broadly appeal across the country, not just in a particular region. This is what Huckabee and others claim the Electoral College was designed to do: ensure that the winner has “broad support across the nation.” Does the state winner-take-all Electoral College design we live with now guarantee the winner must have support across the country? Hardly.

The map below shows that if a candidate really wanted to limit their campaign visits and still win the Electoral College, they wouldn’t fly all over the country to different regions, they could stay east of the Mississippi and still win in a landslide. They could even focus almost entirely on Appalachia and ignore most of New England or much of the Great Lakes and get to 270.

The winner-take-all Electoral college doesn’t force candidates to appeal across the country. Quite the contrary; it means they can win while only appealing to a sliver of voters. A candidate who won narrowly in the states below would have a landslide Electoral College victory by winning over just 30 percent of voters.

Where would presidential nominees campaign with a national popular vote? Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

If every vote counted, candidates would have to appeal across the country to win over most voters.

The argument that if every vote counts equally then votes from city-dwellers will count more doesn’t make a lot of sense on its face. If every vote counts equally and a candidate has to win more of them to win then. . . every vote counts. Votes in cities wouldn’t count for more.

And if you want a candidate to have to reach out to voters across the nation, what better way to do that than to make every vote across the nation actually count? In contrast, the state-winner-take-all Electoral College approach means candidates completely write off most states and all the voters in them. Candidates don’t visit Wyoming or North Dakota or Oregon. Trump didn’t bother trying to appeal to voters on the west coast. Biden didn’t need to appeal to voters in the mountain west. Why would they? Those electoral votes are already locked up. But with a popular vote, there would be voters to win over everywhere and every voter could push you closer to victory, no matter where they live. There are

If enough states join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, agreeing to assign their Electoral College votes based on the national popular vote, not their own state’s vote, we’d tip the scales to a popular vote for everyone.

Democratic voters in Alabama whose votes can’t mathematically matter now, but with a national popular vote Democratic candidates would be motivated to go and speak to them. There are Republican voters in California whose votes will never matter now in the Electoral vote tally, but republican candidates trying to win a national popular vote would try to appeal to them.

Some commentators look at Donald Trump and Newt Gingrich’s about-face on the Electoral College (they were previously not fans, but felt differently with a few Electoral College wins—with popular vote deficits—under their belts) and think that Democrats will do the same, deciding that the Electoral College is a good thing because their candidate won. But the distortion of the Electoral College is top of mind, no matter your political leaning. Donald Trump won in 2016. Joe Biden won in 2020. Most Americans, on both sides of the aisle believe the people should pick the president.

And we could bypass the state winner-take-all Electoral College’s distortion of our democracy without a constitutional amendment. If enough states join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, agreeing to assign their Electoral College votes based on the national popular vote, not their own state’s vote, and equaling 270 electors, we’d tip the scales to a popular vote for everyone.

Kristin Eberhard, Director, Climate and Democracy and author of Becoming a Democracy: How We Can Fix the Electoral College, Gerrymandering, and Our Elections, is a researcher, writer, speaker, lawyer, and policy analyst who spearheads Sightline Institute’s work on democracy reform and on climate action. She researches, writes about, and speaks about elections systems and democracy reform, with particular expertise on Vote By Mail and proportional representation. Eberhard lives in Oregon, an all-Vote By Mail state. She is available to discuss tested, safe, fair COVID-19 election practices, state by state. Find all Eberhard’s latest research here.

For press inquiries and interview requests, please contact Anna Fahey.

Steve Erickson

The Electoral College system is just one of several problems embedded in the constitution that appear to be impossible to fix with constitutional processes. I increasingly think that the Pacific Federation (WA, OR, CA), call it Ecotopia reincarnated if you like, would make a very viable country.

Nick

The “National Popular Vote Interstate Compact” makes no sense whatsoever.The electoral college was made to give the states power, not the people. And back then, the people thought of their state first, country second, all the way up to the American Civil War. In some ways, this attitude still persists. Some Californians wanted to secede when Trump became president.

But if we do, we should replace it with a parliamentary system. We already do have the senate to make sure that states with smaller populations get their fair say.

Still, even if the cities “would not come close to dominating,” they would still have too much influence over elections.