The eastern Cascadian states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming are about as similar as any three states can be. They are neighboring, lightly populated states in the Rocky Mountains, with major agriculture, energy, mining, and tourism industries. Among the reddest of red states, they have Republicans in every state executive office, Republican supermajorities in every legislative chamber, huge majorities for Republican presidential candidates every four years, and, with the sole exception of US Senator Jon Tester (D-Montana), Republicans in all their Congressional seats.

But on one measure of politics, the three states diverge. Montana and, especially, Idaho lag Wyoming badly in voter turnout in local elections.

The reason has little to do with voter ID laws or get-out-the-vote campaigns, with electronic voting machines or any of the other hot-button topics that fuel partisan controversy and distrust about American elections. The reason is much more prosaic: the states’ election calendars.

Idaho and Montana conduct municipal elections in November of odd-numbered years, separate from state and federal elections. Wyoming lets its cities choose when to conduct their elections, and most of them do it on the same ballots they use for federal and state elections, on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even-numbered years. That is, on the date that voters think of as capital-E, capital-D Election Day.

Simply by consolidating elections, Wyoming dramatically boosts turnout. And the consequences include better representation by age; strengthened government accountability to mainstream voters; and saved public funds.

Consolidated elections deliver nearly double the voter turnout

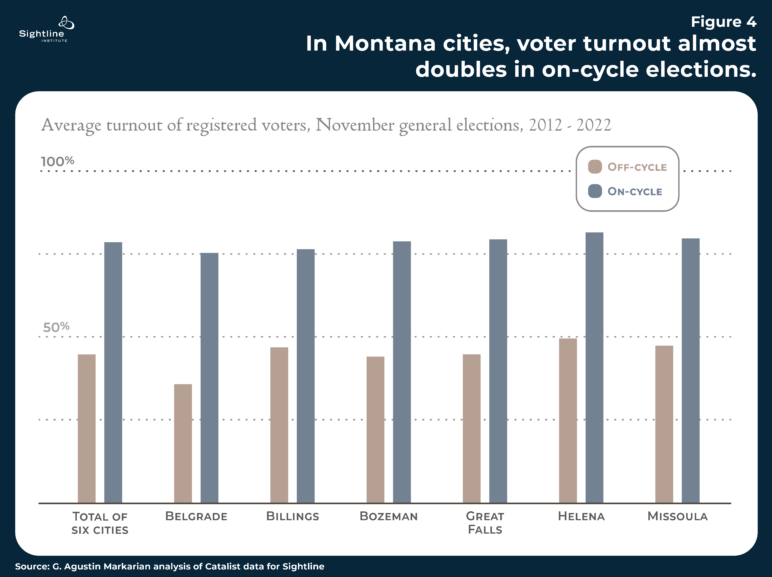

Sightline gathered data from the largest cities in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, finding in each municipality the citywide race with the most votes cast in recent municipal elections. As Figure 1 shows, Wyoming voters cast far more ballots in their 2022 municipal elections, which coincided with state and federal elections, than did their Idaho counterparts in 2021 off-cycle elections, when little else was on the ballot. On average, the Wyoming cities listed in the figure drew 37.3 percent of voting-age citizens to the polls to vote in 2022. In Idaho, meanwhile, the comparable figure was 19.5 percent. In other words, Wyoming’s turnout was almost double Idaho’s, a neighboring state that is otherwise a political twin.

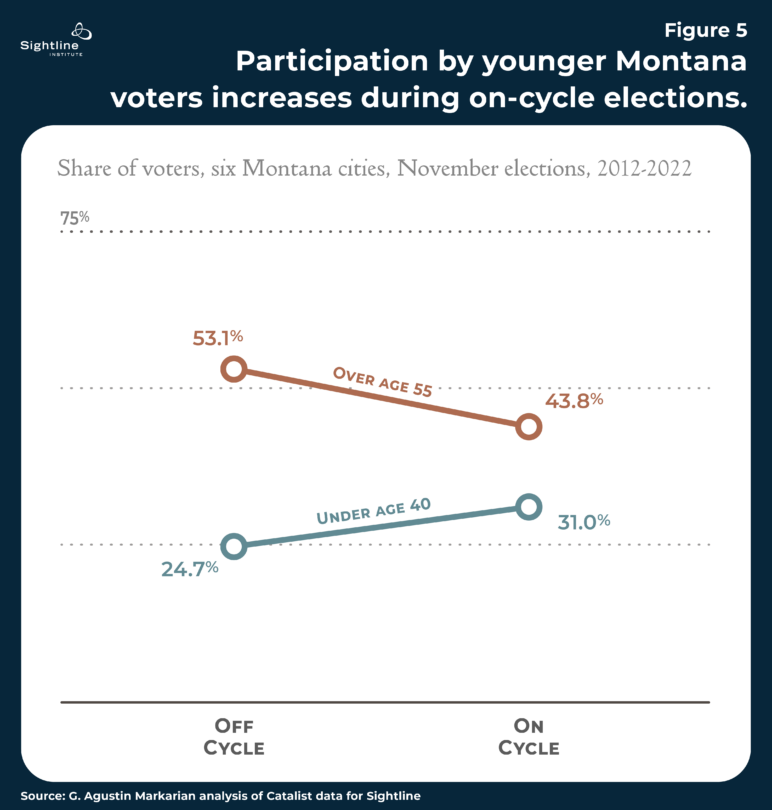

Just so, Wyoming’s municipal voting turnout is substantially higher than Montana’s, as shown in Figure 2. Montana’s odd-year elections brought out more voters than did Idaho’s, but that’s because Montana voters are routinely more active, across the board. In fact, Montana ranks sixth among all US states for its presidential turnout since 1976. Given the much higher voting baseline in Montana generally, you would expect Montana’s municipal turnout to be at least 6 percentage points higher than Wyoming’s. That’s the average gap in presidential elections between the states. Instead, Wyomingites outvoted Montanans by 4.3 points in municipal elections, averaging 37.3 percent turnout to Montanans’ 33 percent. By running local elections with national ones, in other words, Wyoming closes the deficit and goes far beyond.

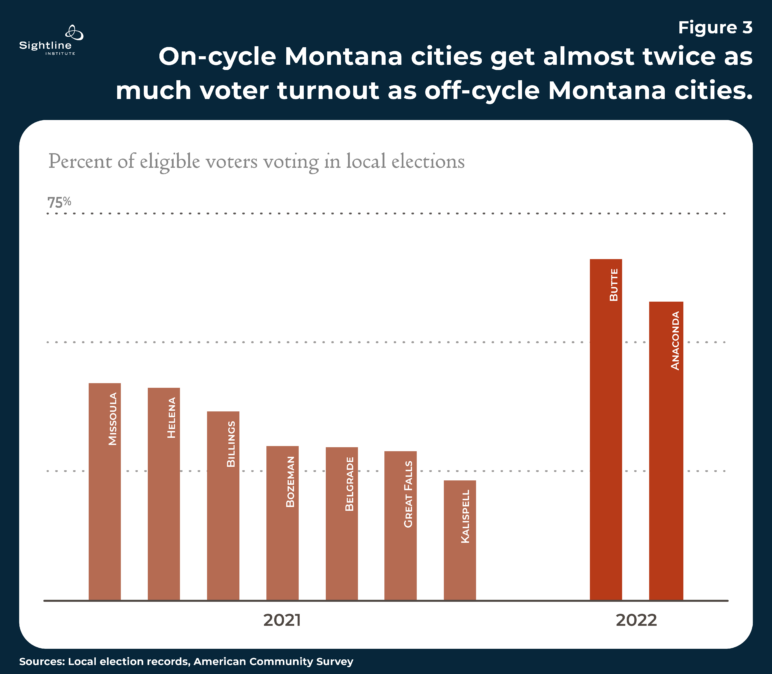

Another way to see the Montana gap between on-cycle and off-cycle voting is to look at the two Montana communities that vote on cycle. By law, all counties in Montana—as in 40 states—vote on-cycle, so the two Montana cities that are run by consolidated city-county governments, Anaconda (Deer Lodge County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), are natural tests of what happens with on-cycle municipal elections. As shown in Figure 3, the on-cycle cities boast almost twice the turnout of their off-cycle peers. Average turnout per citizen of voting age in the highest turnout municipal race in each city in the seven off-cycle Montana cities was 33 percent; turnout in the two on-cycle city/county elections was 62 percent.

Still another way to see the immense turnout penalty that Montana cities suffer from their off-cycle elections is to examine voter participation within city limits in November of odd-number years (when municipal elections are held) with voter participation within city limits in November of even-number years (when national elections are held).

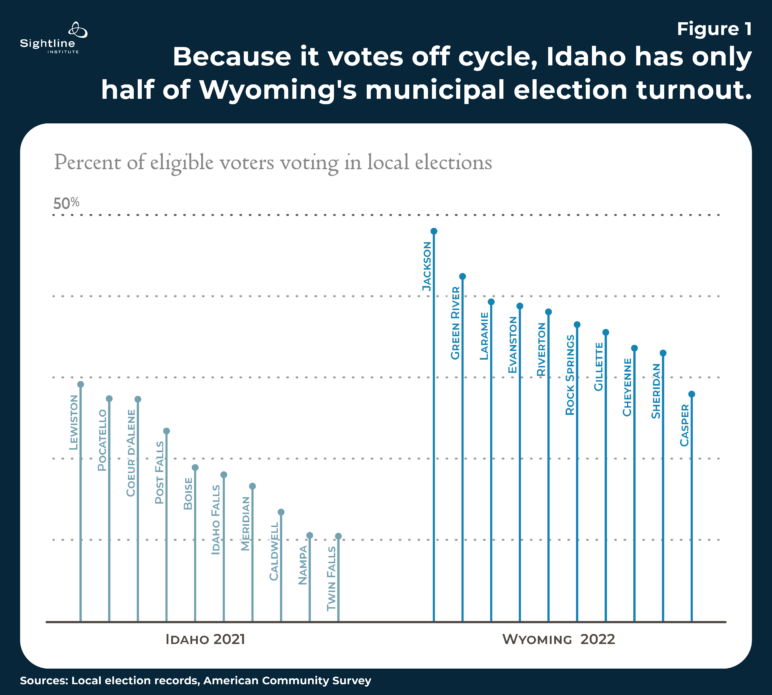

Sightline commissioned research on this question from Professor G. Agustin Markarian of Loyola University Chicago. Markarian used data from a large commercial service called Catalist, which aggregates information from multiple sources to give a detailed view of electorates, to compare who voted in six of Montana’s main cities in a decade’s worth of November elections, from 2012 to 2022.

As shown in Figure 4, in every case, the on-cycle electorate was vastly larger: almost twice as large.

These findings line up neatly with data and research from across the United States. Professor Zoltan L. Hajnal of the University of California, San Diego, writes:

Every one of the eight published studies on local election timing finds that moving to even year elections (often called on-cycle elections) is by far the biggest thing that localities can do to increase turnout. Nationwide, local voter turnout generally doubles when elections move from off-cycle to on-cycle contests.

What’s remarkable about these findings is that other attempts to encourage participation such as get-out-the-vote and registration drives are lucky to boost turnout by just a percentage point or two.

Some opponents of on-cycle elections fret that voters, confronted with a long ballot, quit before finishing. Down-ballot “drop-off” is real, but its scale is usually a few percentage points—inconsequential compared with the boost from on-cycle elections. In Sightline’s comparisons in this article, shown in figures 1, 2, and 3, drop-off is irrelevant: we only tallied ballots marked for local races, so the figures are all after drop-off.

Consolidated elections draw voters who better match the larger population…

…In their age

The consensus of academic research from across the United States points to on-cycle electorates being not only much larger but also more representative. The predominant way in which this is true is that on-cycle voters better match the public in age. Vladimir Kogan of Ohio State University and his coauthors found that in California and Texas, for example, voters aged 65 years or more made up 37 and 39 percent respectively of the presidential-year electorate; their share rose to well over half in off-cycle elections. Among 50 US cities studied by Portland State University, off-cycle elections for mayor brought out mostly old voters; a 17-year gap separated the median age of voters from that of the public in their cities. In cities with on-cycle elections, in contrast, this age gap shrank by half.

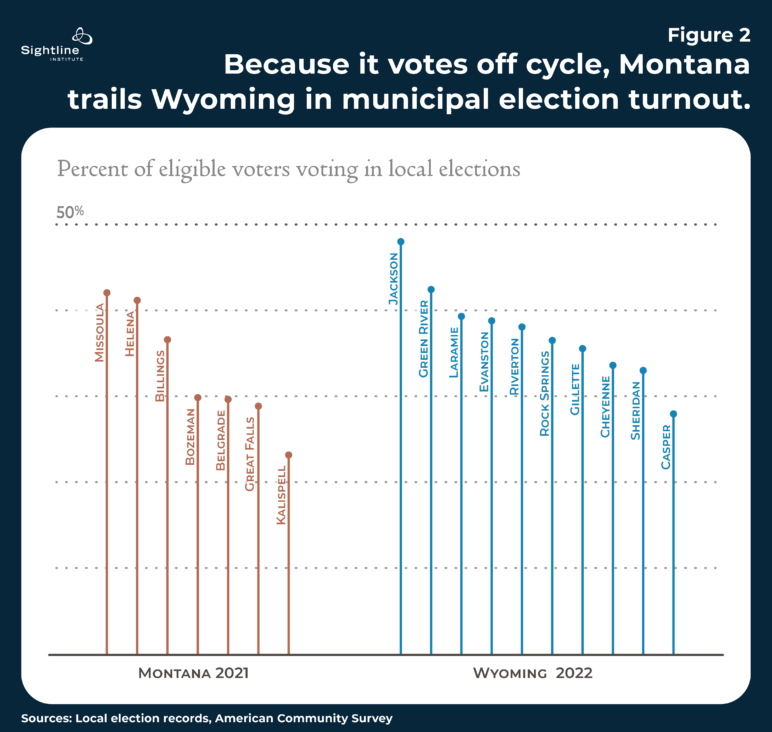

Sightline’s analysis showed the same thing in Montana: the on-cycle electorate in cities includes far more working-age people than does the off-cycle electorate. As shown in Figure 5, in the six Montana cities we studied, over the past decade, the share of voters who were under the age of 40 rose from 25 percent to 31 percent in on-cycle elections, even as the share of the electorate over the age of 55 shrank from 53 percent to 44 percent. It’s not that older voters stay away in even-year elections: everyone is more likely to vote then. It’s just that younger voters flood into the electorate when the stakes are raised by statewide and federal races. Older voters are more likely to vote year in and year out.

…And in their politically moderate identity

Democratic representatives and their political operatives in Idaho and Montana have mostly opposed election consolidation in recent years. They point, for example, to how high-turnout presidential elections have precipitated a red wave in Montana in 2020 and fear that on-cycle local elections would bring out a much more conservative electorate.

But Sightline’s analysis of Montana cities found no big ideological differences between on-cycle and off-cycle voters. Aside from the younger electorate, we found only one meaningful change: on-cycle elections brought a small but statistically significant increase in the share of voters who are political moderates—an increase of 2.8 points. The only other statistically significant finding was a minuscule increase of 0.3 points in the share of voters who are Black, Asian American, or Latino. We found no statistically significant changes between off-cycle and on-cycle electorates in other categories: there was a marginal decrease in Democrats, a tiny increase in Republicans, and an unexpected decrease in average family incomes. But again, none of these findings was of a magnitude large enough to warrant credence: the differences between on- and off-cycle were smaller than the margins of error. Mathematically, the impacts were nil. (See full results here.)

If on-cycle elections favor conservatives in local races, the effect is so small it’s hard to measure. That was the conclusion of an impressive recent study by Justin Benedictis-Kessner of Harvard University and Christopher Warshaw of George Washington University. They assembled an immense new database on local US elections, subjected it to a battery of sophisticated statistical and methodological tests, and sought correlations with a bevy of outcomes. They found that, in contrast with other recent research suggesting on-cycle elections might benefit progressives by better-representing voters of color, the measurable impacts of on-cycle elections were, again, nil: “Moving local elections on-cycle . . . has negligible effects on the partisan composition of the electorate or the partisan and ideological outcomes of elections.”

Consolidated elections dilute special-interest sway and save money

So, if on-cycle elections are a Godsend to neither left nor right, are they truly neutral in their effects? Unlikely. Anything that doubles turnout will have some effect. Most likely, election consolidation boosts particular constituencies within each large party coalition rather than entire parties or their ideologies. Logically, it must elevate the interests of working-age voters at the expense of others.

Which others? It’s not likely to be older voters, who still dominate the local electorate, even after consolidation. Intriguingly, it may be special interests. Scholars have found evidence that on-cycle elections may dilute the power of public employee organizations, such as teachers’ and firefighters’ unions, which—with the exception of police unions—are central members of the Democratic Party’s political coalition. Writes scholar Michael Hartney for the conservative Manhattan Institute:

Studies have shown that off-cycle local elections tend to give organized interests extra power in local politics. Among these interest groups, public-employee unions loom large, especially teachers’ unions. Over several years, I collected data on thousands of teacher-union endorsements in school-board elections in California. In nearly 2,000 board elections held during 1995–2020 . . . union-endorsed candidates did significantly better in off-year races. . . . The electioneering advantages that public unions have in off-cycle elections pay off in policymaking. In several studies, Sarah Anzia has shown that teachers and firefighters receive more generous pay and benefits (including more generous pension commitments) when schoolboard and municipal elections are held at odd times of the year.

In fact, in another paper, Hartney and two coauthors found that US cities with on-cycle elections have policies that vary directly and predictably with the political beliefs of their citizens by, for example, spending more in liberal than in conservative cities. In cities with off-cycle elections, though, they found that public policies that affect public employees—such as pay rates and numbers of workers—display no such relationship. Off-cycle elections, that is, seem to insulate public employee unions from accountability to voters’ beliefs.

What’s more, election consolidation comes at no cost to the public treasury. To the contrary, adopting on-cycle voting typically saves money. In Idaho, Sightline estimates that consolidating all local elections might spare governments $5.4 million in spending per biennium, and in Montana, the savings might be $4.4 million. Together, that’s almost $10 million per two-year election cycle, or $5 million per year.

A history: From breaking up old urban political machines to modern-day maneuvering for change

More than a century ago, from 1894 to 1917, the Progressive movement set about breaking American cities’ “political machines,” in which local bosses used patronage networks to generate huge turnout of local voters for state and national parties. The Progressives’ motives and record were mixed: they aimed to fight corruption, it’s true. But they did it partly by disenfranchising ethnic and working-class voters. Their first tactic and one of their most successful was to disconnect local elections from state and national ones, by shunting them to springtime or to odd years. This splitting of local from state elections stuck, and a large majority of US municipalities still hold their elections off cycle.

Still, the trend is now running back toward on-cycle elections, and Wyoming has been part of that trend. Most cities there were off cycle in 1940, but by 1986, they had moved on cycle, according to scholar Sarah Anzia (page 76). Since 1973, state law has set the default, but not mandatory, method for municipal elections as that they be “held at the same time, in the same manner, at the same polling places, and are conducted by the same election officials, using the same poll lists, as the statewide . . . general elections.”

Neither Idaho nor Montana has ever had on-cycle municipal elections, as far as Sightline’s historical research can ascertain. In 1885, four years before statehood, Montana’s territorial legislature scheduled municipal elections on the first Monday of April each year (see Section 4748). With two-year terms for most mayors and city councilors, the result was a mix of odd-year and even-year spring elections. Then, in 1935, the legislature shifted them all to the odds, still in April, and fixed all terms at two years (see Chapter 381, Section 5003). Sometime between 1947 (see 11-709, 5003) and 1978 (see 13-1-104 (2))—online records don’t say when but suggest it may have been in or before 1969, according to Dan Clark, director of the Local Government Center at Montana State University in Bozeman—lawmakers moved municipal elections to November, where they have stayed ever since.

In Idaho, meanwhile, the current schedule of November odd-year municipal elections has been embedded in state law since at least 1978 and probably since 1961 (see pages 144-145). For several decades before that, just as in Montana, city elections were in April of odd-numbered years, according to Andy Brunelle of Boise, who has held a lifetime’s worth of state and federal leadership roles including as an election clerk in the office of Idaho’s Secretary of State in the 1970s.

In 2023, both Idaho and Montana considered legislation to move local elections on cycle. In Idaho, Senate bill 1079 would have moved municipal elections to November of even years. The bill, sponsored by C. Scott Grow (R–Eagle), didn’t make it out of its first committee. Representative Joe Alfieri (R–Couer d’Alene) offered the narrower House bill 58, which passed the house but didn’t get a final vote in the senate. It would have taken a timid first step toward consolidation by moving votes on school levies and bonds from ultra-off-cycle, stand-alone elections in March and August to the regular primary and general elections in May and November, though not necessarily in even-numbered years.

Meanwhile, in Montana, the state house passed a comprehensive consolidation bill, covering all local jurisdictions from irrigation and school districts to municipalities, and the state senate passed a thinner bill that covered just municipalities. Neither bill got out of committee in the opposite chamber before the legislative clock ran out. In Montana, proponents of consolidation will try their luck with legislators again.

Honoring the founding principles

The most important finding of empirical research is that on-cycle elections favor candidates whose values match public opinion. Hartney, writing with researcher Sam Hayes this time, compared school board members’ views with their constituents’ and found that school boards elected in even years match public sentiments better than do boards elected in odd years. UC San Diego’s Zoltan Hajnal, meanwhile, has conducted research not yet published showing that on-cycle elections dampen the polarization that increasingly bedevils American democracy: moderate voters are better represented in local elections in November of even-numbered years.

The whole point of representative democracy in the United States, as described in its founding documents and the Federalist Papers, is to align government action with majority sentiment, while protecting the freedoms of individuals and of political, religious, and racial minorities. Election consolidation, therefore, ought to be a priority for small-d democrats and proponents of the small-r republican form of government, regardless of which capital letter they identify with.

And in Idaho and Montana, the simplest way to strengthen democracy is to borrow a page from Wyoming and let cities move their elections to Election Day. It could double turnout, even while it saves the states as much as $5 million per year between them.

Data in support of the five figures and explanation of Sightline’s methods are posted here. Thanks to Senior Research Associate Jay Lee for data analysis, to Sightline Fellow Todd Newman for legal research, and to G. Agustin Markarian for data analysis. Thanks also to Zoltan Hajnal for his comments on a draft and for suggesting and advising on the voter file analysis conducted by Dr. Markarian.