The Electoral College gives a numerical advantage to small states. Because each state gets two Electoral Votes for its two senators, no matter how many people live in the state, smaller states have more Electoral College representation per voter. For example, a voter in Wyoming has four times as much say in the Electoral College as does a voter in Texas. But despite getting a bump in Electoral Votes relative to their populations, small states that vote consistently red or blue are still just spectator states in the current state-winner-take-all system. In practice, a voter in Wyoming counts for just as much as a voter in California. Nothing.

In other words, small states’ numerical advantage doesn’t translate into political advantage. If all the small states leaned the same way, the Electoral College would put a heavy thumb on the scale in favor of that small-state-favored political party. But small states don’t all lean one way.

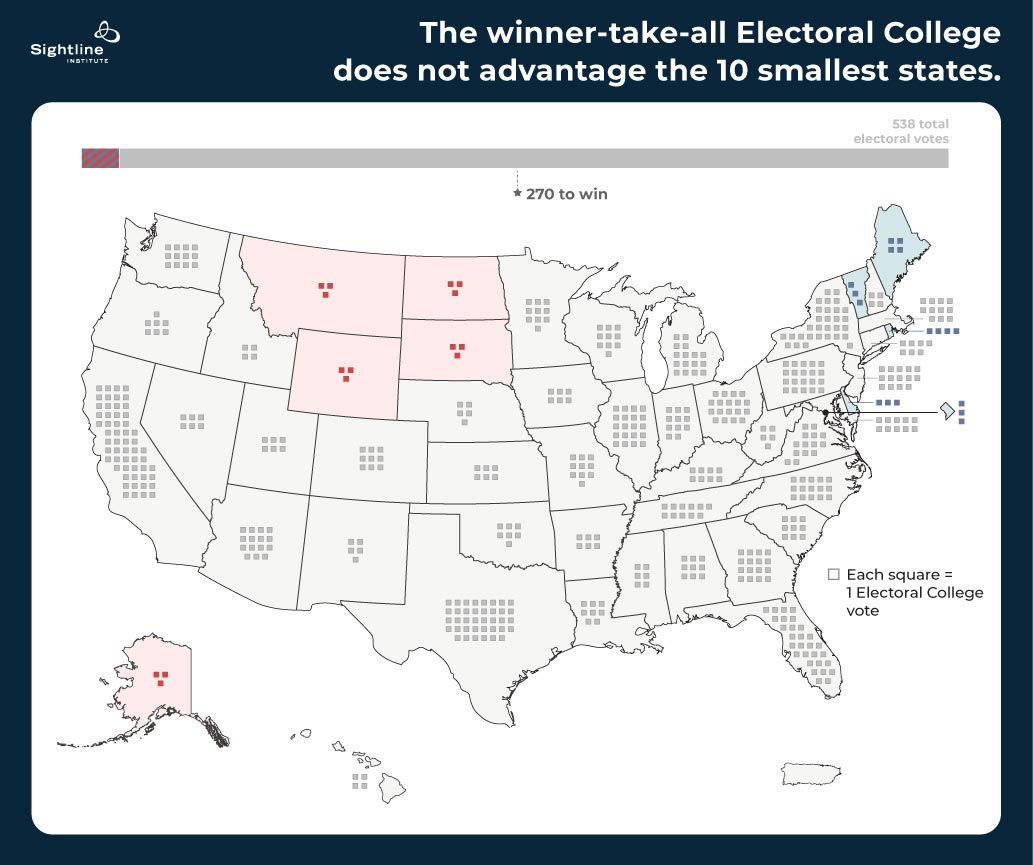

The ten smallest states are evenly split, five red and five blue

Of the ten smallest states, five are safe blue states (Maine, Vermont, DC, Rhode Island, Delaware) and five are safe red (Alaska, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota). In other words, they don’t have a shared “small state” political agenda for the Electoral College to protect. The fact that the smallest states all lean heavily toward one party or the other might not be entirely accidental. Small states tend to have more homogenous populations, making it more likely that they will lean toward one party.

In the map below, each square represents one Electoral College vote, and the ten smallest states are blue or pink according to which party has consistently won in that state in recent decades.

The Electoral College doesn’t actually protect small states. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

Even though they have more Electoral Votes than they would based on population, these 10 states still only boast 32 Electoral Votes between them, which is only three more than the state of Florida. Faced with seeking support from 10 states with widely varying values, or trying to win over a single state for nearly the same political advantage, political parties pay more attention to big Florida than to the 10 small states.

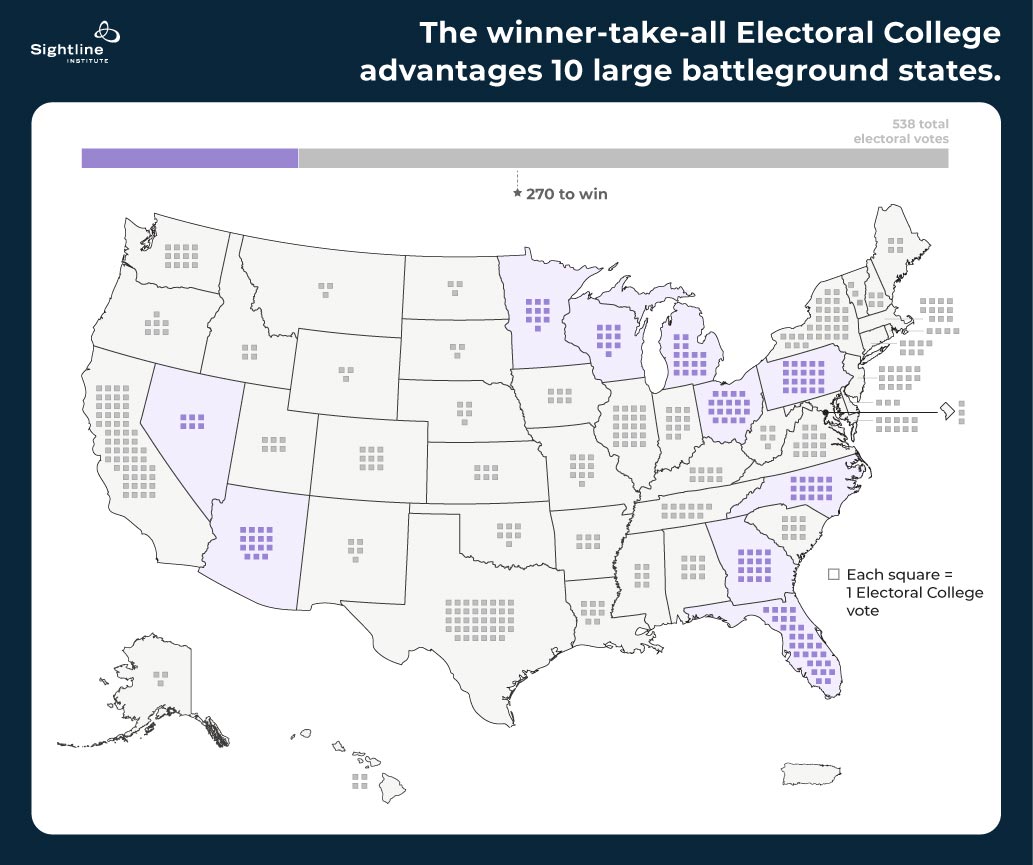

The ten battleground states are big

The presidential race is fought and won, not across the country as a whole, and not in small states, but in battleground states. These are the handful of states where the margin between the two major parties is thin, and so all their Electoral College votes are up for grabs under the state-winner-take-all system. This is where candidates campaign, campaigns spend money, and presidents spend more federal funds once in office to boost their chances of reelection. Battleground states are the ones that matter. And they are big states.

Of the ten main battleground states in 2020, six of them are in the top ten biggest states. And nine of them are in the top twenty largest states. The only one that’s not is Nevada.

Again, that’s not coincidental. Bigger states have more diverse populations, making it more likely that voters might be closely divided, creating stiff competition between the two parties. The state-winner-take-all model makes closely divided states more important, and bigger states may be more likely to be closely divided (see big, diverse Texas trending toward battleground status).

Plus, bigger states offer more bang for their buck, more Electoral College votes per victory. Together, these ten battleground states hold 151 electoral votes, nearly five times as many as the ten smallest states. Campaigning in and winning Florida gives 29 Electoral votes for one state victory, compared to just three for a victory in Wyoming.

Small states and big safe states are mere spectators. Original Sightline Institute graphic by Devin Porter of Good Measures, available under our free use policy.

Spectator states don’t matter

All the gray states in the map above are “safe” for one party, which makes them mere spectators to the presidential race that plays out in battleground states. Because all of their Electoral Votes are locked up from the outset, candidates don’t bother campaigning in those states. They don’t bother trying to win over voters in those states because winning extra votes there won’t help them win any more Electoral Votes. Despite more Electoral Votes relative to their populations, small states are still spectator states in the state-winner-take-all system. In practice, a voter in Wyoming counts for just as much as a voter in California. Nothing.

We can make every vote for president count

Because almost all states currently give all their Electoral Votes to a single candidate, even if many voters within the state voted for someone else, a voter in little, safe Wyoming or Vermont matters much less than a voter in big, battleground Florida or Pennsylvania. But if every vote counted equally, if the candidates were seeking to earn the most votes across the country, then every voter would hold more power and get more attention from candidates and campaigns. Winning over a voter in Wyoming would be just as important on the path to victory as a voter in Florida, so candidates would not spurn Wyomingites in favor of Floridians.

We the people can make the Electoral College better reflect the will of every voter, not just swing state voters. If more states sign on to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, then the campaign for president in 2024 could be a campaign where all American voters matter equally no matter where we live or the party other voters in our state may favor.

Kristin Eberhard, Director, Climate and Democracy and author of Becoming a Democracy: How We Can Fix the Electoral College, Gerrymandering, and Our Elections, is a researcher, writer, speaker, lawyer, and policy analyst who spearheads Sightline Institute’s work on democracy reform and on climate action. She researches, writes about, and speaks about elections systems and democracy reform, with particular expertise on Vote By Mail and proportional representation. Eberhard lives in Oregon, an all-Vote By Mail state. She is available to discuss tested, safe, fair COVID-19 election practices, state by state. Find all Eberhard’s latest research here.

For press inquiries and interview requests, please contact Anna Fahey.

Troy

The electoral College keeps the large population states from being the only 1’s who elect the president. M.h a kg es it fair for All states.

uncus

“Of the ten smallest states, five are safe blue states (Maine, Vermont, DC, Rhode Island, Delaware).”

DC is not a State.