Oregon’s first-in-the-nation automatic voter registration (AVR) system continues to modernize the state’s elections system and lead the way for other states. By making better use of existing digital data, the Beaver State has registered almost all eligible citizens to vote, and it is keeping their information up-to-date so that mailed-out ballots go to voters’ correct, most current addresses. It is working so well that 19 other states (including Alaska and Washington) plus the District of Columbia have followed suit in recent years.

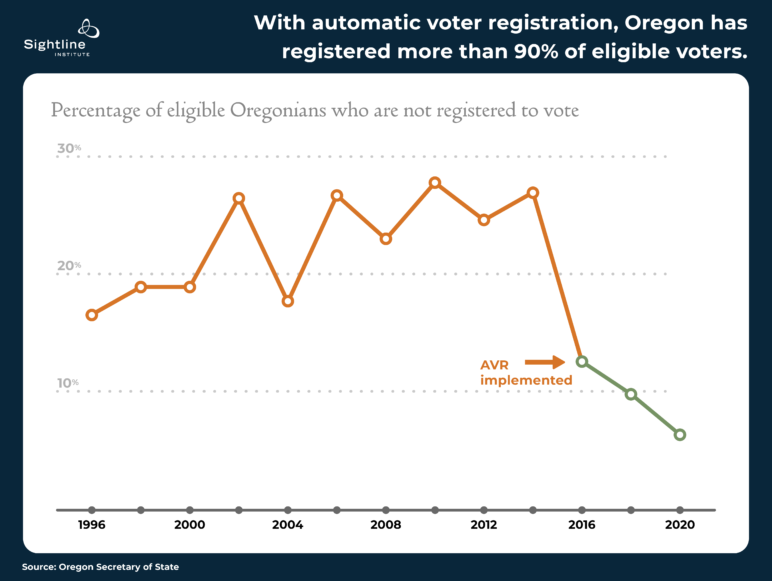

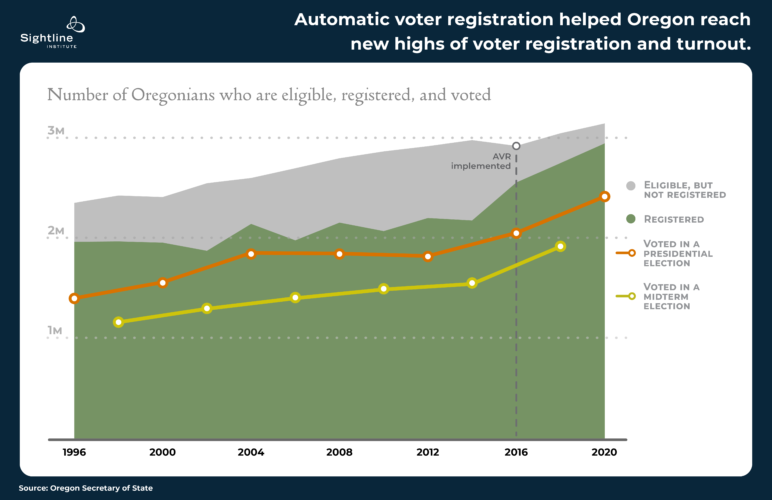

In Oregon, AVR has registered more than 800,000 new voters—that’s more than one-quarter of the state’s almost three million total registered voters. It has also updated voters’ information 1.5 million times; as many as half of Oregon voters might have had outdated registration information if not for AVR. After the policy was implemented in 2016, almost 95 percent of eligible Oregonians (adult citizens not disenfranchised due to a felony conviction) were registered to vote in the November 2020 election. Fewer than 200,000 eligible voters in Oregon remain unregistered. Of that group, 53,000 have opted out since AVR’s implementation, so as few as 145,000 people in Oregon are eligible to vote and potentially interested in voting but not yet registered. Many of those many not have gone through the 8-year cycle of renewing their ID since AVR was implemented five years ago. Nonetheless, that number is an eye-popping improvement since 2014, prior to AVR, when more than 800,000 Oregonians were eligible to vote but not registered. And it will continue to shrink as more people renew their ID in the next few years.

Oregon implemented an AVR system in 2016, leading the nation in this facet of efficient and modern election administration. The Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) or other state agencies automatically forward eligible voters’ data to the Elections Division, which uses the information to register new voters and update already-registered voters’ information. Under the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (“Motor Voter”), states are required to offer an “opt-in” registration process to applicants at the DMV or public assistance agencies: while filling out paperwork at the DMV, eligible voters also receive paperwork allowing them to register to vote. Oregon took this reform a step further in 2016 by converting it to an “opt-out” system. The DMV automatically transmits eligible voters’ information to the Secretary of State’s office. The Secretary registers them to vote and sends them a postcard with the option to opt out if they don’t wish to be registered to vote. This process saves effort for the registrant and is believed to enroll more voters than a system in which potential registrants opt in while at the DMV. Many would-be voters don’t take the extra steps needed to get registered under the opt-in system, so the opt-out captures more eligible voters.

AVR is more efficient because it utilizes information that a different agency is already collecting and transfers it digitally, thereby avoiding duplicative and potentially error-ridden paperwork. It also keeps voter rolls accurate and up-to-date by both registering new voters and updating the addresses of existing voters who moved but did not update their voter registration record.

AVR has helped Oregon close the age gap in voter registration. In the United States generally, and in Oregon prior to AVR, older Americans are more likely to be registered to vote than younger people, in part because they have had more time to get registered, and in part because they tend to move around less so their registration stays current. Younger people are just getting registered for the first time and tend to move often, and so they have to jump through the hoops to register again. Studies find that AVR registrants are “younger, more rural, lower-income, and more ethnically diverse.”

Naysayers might think that people who wanted to vote would have registered already. But AVR shows that making it easier to get and stay registered encourages more people to vote. Of all Oregonians registered via AVR, 43 percent voted in the November 2016 election. Since the people registered via AVR are younger, less educated, and less wealthy—all factors that make them less likely to vote than the general public—political scientist Barry Burden described this relatively high participation rate as “quite a feat.” Even the Oregonians who were unlikely to have registered at all if not for AVR had strong turnout rates: 34 percent cast a ballot in 2016. In other words, AVR successfully encouraged tens of thousands of Oregonians to participate in the electoral process who likely otherwise would not have.

With all of these new registrants and voters drawn in by AVR, Oregon continues to outvote much of the nation and even outdo its own past turnout rates. In the November 2020 presidential election, more than three out of four (77 percent) eligible Oregonians cast a ballot—a higher turnout rate than all but five other states. Oregon has only topped 70 percent turnout in two previous elections since 1966 (the earliest year that data is available), the 2004 and 2016 presidential elections. The state saw the highest increase in voter turnout among any state from 2012 to 2016, the year when AVR was first implemented. Oregon has also set high water marks for midterm and primary elections since the passage of AVR: its 63 percent turnout in the 2018 midterm outpaces every midterm since at least 1966, and its 42 percent turnout rates in the 2016 and 2020 presidential primaries are unsurpassed since the 1980 primary election.

With so few people left unregistered, advocacy and get-out-the-vote groups can turn their attention to voter mobilization efforts in Oregon instead of registration drives. Fewer than 200,000 eligible Oregonians were unregistered in the 2020 election, but more than twice that figure did not cast a ballot (530,000). Registration drives may still be helpful, though, for the 150,000 15- to 17-year-olds in the state, as they become eligible for preregistration and eventual voting but may not get picked up by AVR as soon as they turn 18.

Political parties might also turn their attention to encouraging newly AVR-registered Oregonians to vote. AVR registrants are less likely to affiliate with a political party, and Oregon’s closed primary system means that these unaffiliated potential voters are excluded from primary elections for the two major parties. Voters affiliated with a party vote more, even in general elections—AVR registrants affiliated with a party voted in November 2016 at about the same rates as their traditionally-registered peers, while unaffiliated AVR registrants turned out only half as much as unaffiliated traditional registrants. Now that most Oregonians are registered, parties (including Oregon’s six minor parties), advocacy organizations, and get-out-the-vote groups can play a role in increasing voter turnout and ensuring that every Oregonian has their voice heard in the electoral process.